For the last decade, Rob Roensch’s short fiction has been relentless in its portrayal of human sensitivity and vulnerability. Often taking place in peripheral landscapes at odd hours of the day (places like the Brook Run Townhome and Apartments or the Hundred Pines Mall), Roensch’s characters’ instinctive sentience keeps them alive in a world otherwise left for dead. Their labor is drudge work—they stock shelves, they bus tables at the Olive Garden—and if you’re looking for a romanticization of working-class life, you won’t find it in his pages. However, what you will find are characters who, despite the tedium of their exhausted lives, know things: where the secret door is that gets you into the mall after hours; how to properly experience an echo; when not to play the guitar.

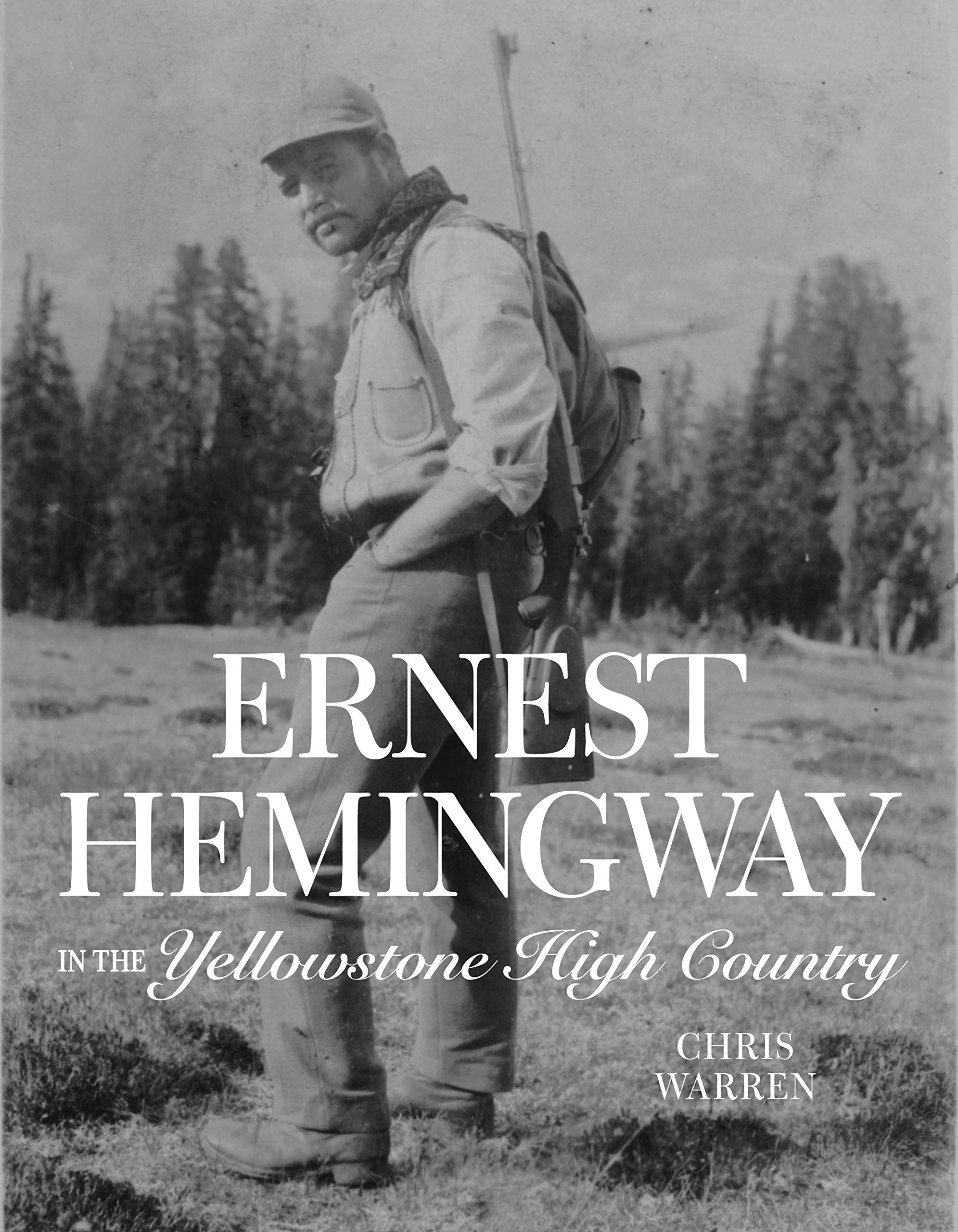

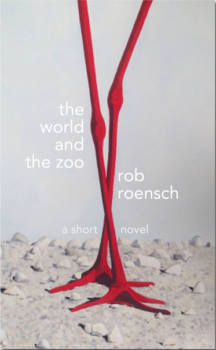

Some of Roensch’s stories of the last decade were published in his excellent collection The Wild Flowers of Baltimore (Salt, 2012), while others—equally good—have been scattered in reputable print and digital magazines. My favorite story of his I heard once, out loud, and have yet to see it published anywhere. Which is, in part, why I was so excited when I got my hands on his new novel, The World and the Zoo (Outpost19).

The book does not disappoint. In fact, one of the fascinating things about it is watching Roensch take the familiar themes and forms from his short stories and work them through the space and possibility the novel affords. And it works like you wouldn’t believe: Roensch’s novel—which follows Zack, a recent college graduate who takes a summer internship at the Oklahoma City Zoo—is so precise in grounding the reader in the here and now of human/animal interaction/observation/care, that you almost lose track of its bigger, more important questions. Almost. Because like his short fiction, his novel is always reaching out and asking: what are the limits of human consciousness? Where are the edges of our empathy? When can we feel the most?

Interview:

George McCormick: I want to begin by making a big claim: this novel takes ideas of transcendentalism seriously. The novel would never use that term verbatim, as old-timey as it sounds, but the ideas are there—that there is a world adjacent to this one, that there is a consciousness within reach of our own daily consciousness that has access to a world that is more alive. I want to say more human, but I don’t know if that’s right or not. Maybe that’s one of the central questions of the book?

Rob Roensch: Yes, that’s right, I hope. I would probably use the word “within” as opposed to “adjacent.” But yes, this character has an intimation that there is more to the world than the world. A persistent feeling that what seems to be agreed upon as good and true and real by society is not quite right. An almost physical sensation that everything is slightly out of focus, like you are seeing through bad lenses, like getting fitted for a new prescription at the eye doctor and that if you can only find the secret knob, and turn it just right, the truth will shine forth. (I may have just gone to the eye doctor.) The important decision Zack makes, I think, is to listen to that feeling, that intimation of another truer world at hand, instead of ignoring it or arguing it away. I think that feeling of uncertainty and yearning is important to live with.

I like how the novel portrays Zack’s intimation and pursuit of another world as an act of courage, because it is. Yet the opportunity to act courageously is made possible, in part, by his social status. He can afford to be a tourist in the world of the transcendental.

I like how the novel portrays Zack’s intimation and pursuit of another world as an act of courage, because it is. Yet the opportunity to act courageously is made possible, in part, by his social status. He can afford to be a tourist in the world of the transcendental.

That’s well put. He’s able to put months into what he thinks of as a quest for meaning (but could also be described as following a whim) because of his family support, his wealth. One of the things I hope he is just beginning to learn by the end of the summer is to recognize not only what he’s seeing but where he’s seeing it from. To recognize that there is no such thing as a quest for spiritual and aesthetic meaning divorced from a full and honest accounting of both the physical world, life and death, and the social world, the political world, and how he fits within that world. He’s not there yet, of course. It’s only one summer; he’s still young and in some ways unformed. But I hope he’s learned enough about himself and the world to set himself on a path to that sort of understanding.

I feel like you figured something out with the writing of this book in that you are able to take acts that are almost always passive—acts of looking, observing, gazing—and make them into something active. It feels almost like a psychedelic approach.

I’m relieved to hear that all the looking reads as active—that was a goal of mine. A book that inspired me is Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer. In that book, the main character, Binx, becomes alienated from his own history and life and goes on a deliberate (and ridiculous at times) search for meaning. One of the answers Binx in The Moviegoer eventually comes to is Catholicism; the mysterious other more-alive world is the spiritual/religious world. Zack doesn’t have access to that kind of faith, or even that language. But he’s on the same kind of search. Looking can be active, I think, if there is some kind of purpose, if there’s a question motivating it, even a question that can’t completely be articulated. I hope that’s what’s happening in The World and The Zoo.

I think it is. And you’re right that while Zach doesn’t have access to the language of faith like Binx does (and this becomes clear in the wonderful, understated, conversations he has with Charlotte), but he does have access to a language that connects aesthetics with something close to spirituality. Here I’m thinking about what he learns from his mother, and that description of the difference between the “upstairs” paintings and the “downstairs” paintings in his boyhood home.

I think a lot about how we all see the world differently and how we come to see the world the way we do. We all see first from who we are in the world and who the world sees us as, from our bodies, from our hometowns. And those perspectives can have specific insights, as well as specific limits and blindnesses. The question that comes next, to oversimplify it, is how is it possible that two people from the same hometown can see the world differently? I think part of the answer could be the way we absorb from the world not just what we see but ways of seeing, languages of seeing.

Zack seems to get from his father a way of looking at people, and from his mother a certain way of thinking about beauty. And practicing those ways of seeing take him to a different perspective than either his father or mother sees from. Another part of the answer is, I think, more mysterious. Can we choose to find our own language of seeing? To see ourselves into a truer, deeper way of seeing? I would like to think so. I think acknowledging the error of the inherent sense we have that our way of understanding the world is complete is a first step, a beginning. Living inside the never-to-be-resolved yearning to better see what’s real and true is necessary, and difficult. And it goes without saying that seeing, without acting, is not enough.

The novel is 132 pages long, made up of 66 un-numbered chapters. There are no section breaks. The longest chapter is seven pages, the shortest about a third of a page. When you were writing when did this form begin to emerge? And at one point did you know you had something suitable to sustain a novel?

I don’t ever use outlines and I rarely write chronologically. I acknowledge that for me the whole process is a little mystical. Often what starts a story for me is a hard-to-describe impulse, something like hearing a chime when I for lack of a better word, receive some fragment of a voice, some hint of subject matter, some direction of wondering. And the voices I write with often move in what I think of as breaths of attention, and those breaths can be of different lengths depending on what they want to look at and think about—sometimes a line, sometimes a few lines, sometimes a paragraph. And then I write the story, following the voice, following the rhythm, trying to see what it’s going to see. I never know how long a story is going to be or what I’m going to see when I write it.

What The World and the Zoo started from was this memory of being a younger person and coming home after a long night of partying in some parking lot and looking up at the blank sky and thinking, what I am doing, together with, mysteriously, a memory of being at the zoo, leaning over the fence staring at some animal who doesn’t care about me, this sensation of oddly desperate attention. Then the circumstance of disappearing animals appeared. And I wrote following that. What made the book a short novel and not a ten-page reflection/elegy/portrait-story (as many of the stories I write turn into) was when I found out Zack’s new friend Caroline’s brother was sick. That surprised me just as much as it surprised Zack. That forced the story to open out.

And isn’t it wonderful when you find that sustaining voice? I once had a friend who wrote me a letter from Idaho. He was trying to run his wife’s parents’ bakery while his wife was attending to her sick mother. They had two kids in tow. The bakery wasn’t making any money. He didn’t know what was going to happen next, but the letter was so beautiful and resilient and hopeful in ways that felt profound to me. I remember I sat down at my computer with it and retyped the whole thing and just kept going, in that voice, and a whole story poured out. A week later I had fifteen pages and it was done.

My point is, I know we always talk about writing as a product of time and revision—and it mostly is—and I know we shy away from slippery ideas like inspiration, but I feel like sometimes the writer’s greatest gift is being attentive to the voices in the air, because you never know when one is going to enter into your head.

Your story of where inspiration comes from is wonderful. I love how you are able to explain a sort of absolute openness to a voice that transitions seamlessly into the act of putting words on paper. Writing is so much more about listening than it is about speaking.