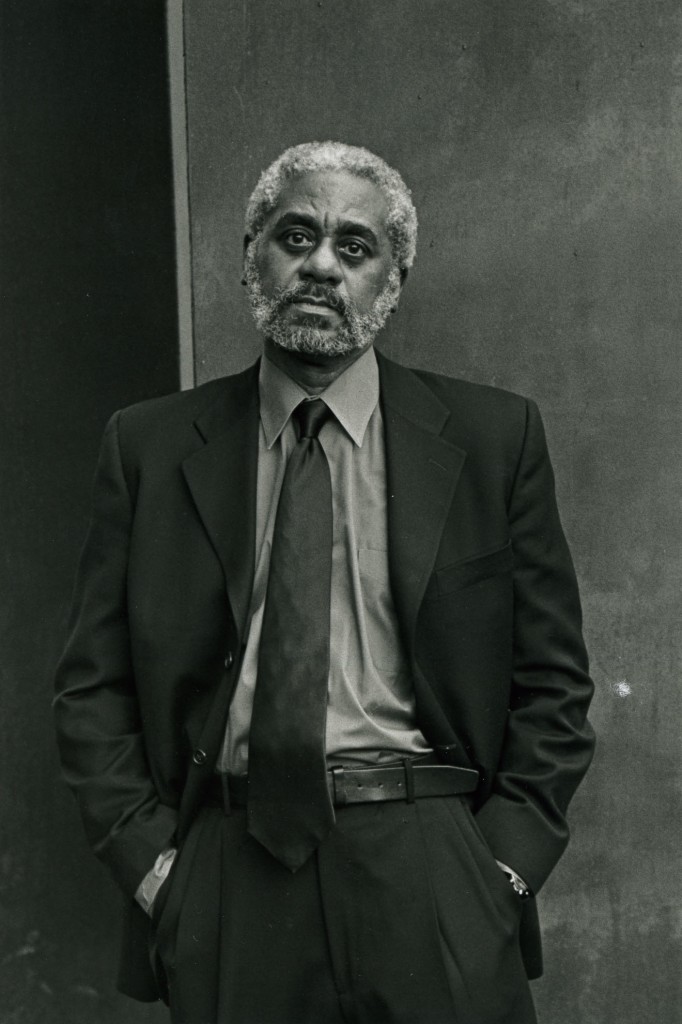

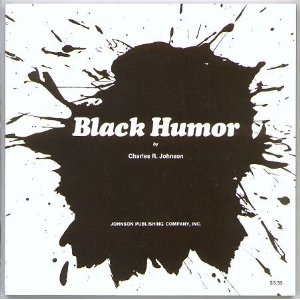

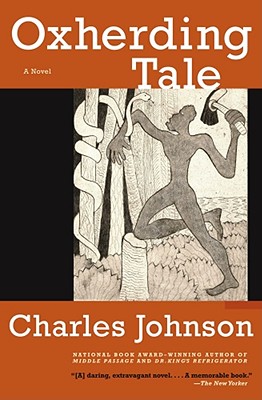

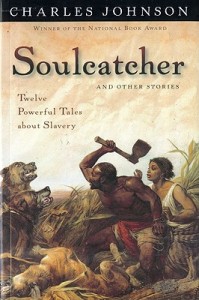

Charles Johnson taught creative writing at the University of Washington from 1976 to 2009. His first book, a collection of political cartoons entitled Black Humor, appeared in 1970 when he was twenty-two years old. In fall 1972 Johnson introduced himself to John Gardner, author of many distinguished novels and then professor of English at Southern Illinois University. Under Gardner’s tutelage, Johnson began writing his first published novel, Faith and the Good Thing. His critique of the phenomenological aesthetics of contemporary African American fiction, Being and Race: Black Writing Since 1970, appeared in 1988. Following the well-reviewed Oxherding Tale (1982), Johnson wrote his masterpiece, Middle Passage (1990), which won the prestigious National Book Award, making him just the second African American male to win the prize, following Ralph Ellison in 1953 for Invisible Man. Johnson published a fourth novel, Dreamer (1998), and three collections of short fiction: The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1986), Soulcatcher and Other Stories (2001), and Dr. King’s Refrigerator and Other Bedtime Stories (2005). Some of Dr. Johnson’s essays about his spiritual life and Buddhist philosophy appear in Turning the Wheel: Essays on Buddhism and Writing (2003). Charles Johnson has written more than twenty screenplays, including the script for the prize-winning PBS film of Booker T. Washington (Booker, 1985). Moreover, he has written or edited the text for such nonfiction books as Black Men Speaking (1997), Africans in America: America’s Journey Through Slavery (1998), King: The Photobiography of Martin Luther King Jr. (2000), and Mine Eyes Have Seen: Bearing Witness to the Struggle for Civil Rights (2007). Dr. Johnson’s body of work has garnered many prizes, most notably a MacArthur Fellowship (1998), and an American Academy of Arts and Letters Award for Literature (2002).

During the last few years that Dr. Johnson taught at the University of Washington, I was lucky enough to study with him in UW’s MFA program. I grew up in New York and New Jersey and lived a mostly nomadic life in my twenties; I sold bread, washed dishes, built rock staircases in the Adirondacks, doled medication to schizophrenics in a halfway house, drove a truck and planted trees for a nursery in Albuquerque. When I moved from New Mexico to Seattle in 2005 and took my first workshop with him, he led me to new reckonings with regard to how I was able to perceive the world. His example challenged me to consider the possibility of a morally coherent world, a world where all things are possible, including goodness and virtue. His mentorship has been a gift that I am in no way capable of reciprocating.

I am not alone. Counted among his former students are such authors as Johanna Stoberock, G.W. Hawkes, Kathy Alcala, and David Guterson. He’s mentored scores of students, both at the graduate and undergraduate level. And there are dozens—if not hundreds more—whose writing and whose lives he’s challenged and inspired by his work, by his thought-provoking example, and by his kindness, compassion and integrity.

The following interview took place as a series of email conversations in January and February 2010.

Interview:

WATTERSON: Let’s begin with mentorship. Who were your first mentors and how did they contribute to your growth?

JOHNSON: My first mentor was the prolific cartoonist/writer Lawrence Lariar. When I was fifteen I began studying comic art in a correspondence course with Lariar, who published over 100 books, wrote detective fiction under a couple of pseudonyms, was a Disney studio “idea” man, cartoon editor for Parade magazine, and editor of Best Cartoons of the Year. Some summers when I was in high school I’d travel to New York City to see if I could score some assignments with magazines and publications located there, and I’d visit him at his home on Long Island, where he gave me some of his original work and good, professional advice. Back in Evanston, Illinois, my home town, I began publishing my stories and illustrations when I was 17. And for the next seven years that’s what I did when I went away to college, publishing two collections of political cartoons, Black Humor (1970) and Half-Past Nation-Time (1972)  and over 1,000 drawings and illustrations. I also created, hosted and co-produced in 1970 the PBS how-to-draw series, “Charlie’s Pad.” Last week I was at University of Houston-Victoria, and one of my hosts told me he saw the show in Texas in the early 80s when he was a kid. Each of the fifty-two, fifteen-minute lessons was based on the course I took with Lariar between 1963-65, and we stayed in touch until I moved to Seattle to teach at UW in 1976.

and over 1,000 drawings and illustrations. I also created, hosted and co-produced in 1970 the PBS how-to-draw series, “Charlie’s Pad.” Last week I was at University of Houston-Victoria, and one of my hosts told me he saw the show in Texas in the early 80s when he was a kid. Each of the fifty-two, fifteen-minute lessons was based on the course I took with Lariar between 1963-65, and we stayed in touch until I moved to Seattle to teach at UW in 1976.

Could you talk about how John Gardner’s mentorship helped you grow as a writer?

When I met Gardner—when I was in my second, final year of a master’s-degree program in philosophy and working as a journalist on a small newspaper in Southern Illinois (journalism was my bachelor’s degree)—I had already written six novels in a period of two years (the second in that series was an early attempt at doing what later became Middle Passage). Prose rhythm and voice were two things Gardner was skillful at doing, so I began my focus on those elements of craft during the nine months I wrote Faith and the Good Thing with him looking over my shoulder. We hit off it, I think, because Gardner had an interest in philosophy, and I admired the example he offered as an imaginative fiction writer who was also a scholar of medieval literature, a literary critic, a poet, a musician and composer of librettos, a playwright, and not a bad painter (I have one of his still life oil paintings and two sketches of characters from his novel Jason and Medeia in my home.) In his fiction work I saw formal virtuosity, a respect for the moral and spiritual life (at least for Christianity in his case, which I appreciated since I was raised in an African Methodist Episcopal church), and he was as prolific and dedicated to creating as my earlier teacher Lariar. One of the six novels I’d written before meeting Gardner was accepted for publication when I was working on Faith, a book that was very much in the style of James Baldwin, which is why I believe the publisher liked it. I asked Gardner if I should publish it because with Faith I was finally getting a handle on the original approach to philosophical fiction that I’d been trying to achieve. His advice was, “If you think later you’ll have to climb over it, then I’d say, no.” So I requested it back from the publisher, and I’ve always been glad I did. That novel simply wasn’t my philosophical vision so, though it was difficult to turn away from a book contract (every young writer wants to get published), I did, and gambled that Faith would be published when I finished it, which it was when I was twenty-six.

Gardner’s influence helped me understand all of what is at stake when we write. He told me a novel should be as perfect as one can make it before you submit it for publication; he counseled often that, “Any sentence that can come out should come out.” Knowing him ratcheted up my concern with craft—experiments with form as a meditation in itself—and literary aesthetics.

As a philosopher and a Buddhist, you must have had spiritual mentors who influenced you. Can you talk about their impact on your literary and spiritual life?

I can’t say that I’ve had a particular spiritual mentor. But I am fond of the work of scores of Buddhist writers as well as those who follow a spiritual path in other religious traditions. And I took formal vows, the Ten Precepts (as a lay-person or upasaka) with my friend, Claude AnShin Thomas, a mendicant monk and author of At Hell’s Gate: A Soldier’s Journey From War to Peace.

As you know, the poet and memoirist E. Ethelbert Miller is going to be one of the writers who will appear onstage at this tribute event in Denver in April 2010. Would you reflect on your friendship with him?

Poet Miller tells me we first met at a PEN/Faulkner ceremony when my first story collection, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, was a nominee in 1986. I like to call him BrerBert and Mr. Wizard because of all the remarkable things he accomplishes as an arts activist. In this country in general, and in Washington D.C. in particular, he is “Mr. 411,” the person who you call for an answer to any question about contemporary black writers or black culture. He has a heart as big as all outdoors. He is a relentless advocate for emerging and often forgotten writers or those who have not received the recognition and support they deserve. As a matter of fact, he has lobbied to get jobs for writers. There is simply no one like him.

Would you speak about your friendship with the late playwright August Wilson?

I recently published a story (or maybe it’s really an essay) on the fifteen years August and I had eight to ten-hour dinner conversations about Everything until five in the morning here in Seattle at the Broadway Bar and Grill (in other words, until they had to close and kicked us out.). It’s called “Night Hawks,” and appears in the summer, 2009 issue of Kenyon Review. A slightly shorter version (by 1000 words) was published in the spring 2009 Lincoln Center Theater Review when director Bartlett Sher directed August’s play Joe Turner’s Come and Gone—the same performance that President Obama took First Lady Michelle to see. It took me several years after his death to reach a point, emotionally, where I could bring myself to share in a literary work the wealth of impressions and personal details I’d accumulated in my head about America’s most celebrated black playwright. Writing this piece was very hard, because he was my friend and rather like a brother because we were born just three years apart, and grew up in the same cultural and racial worlds of the 50s and 60s. (The latest edition of my novel, Oxherding Tale, has a cover that August came up with, and he gets in the book credit for cover design and art.) I recommend that readers of this interview take a look at “Night Hawks” in Kenyon Review for the full story of our friendship.

I recently published a story (or maybe it’s really an essay) on the fifteen years August and I had eight to ten-hour dinner conversations about Everything until five in the morning here in Seattle at the Broadway Bar and Grill (in other words, until they had to close and kicked us out.). It’s called “Night Hawks,” and appears in the summer, 2009 issue of Kenyon Review. A slightly shorter version (by 1000 words) was published in the spring 2009 Lincoln Center Theater Review when director Bartlett Sher directed August’s play Joe Turner’s Come and Gone—the same performance that President Obama took First Lady Michelle to see. It took me several years after his death to reach a point, emotionally, where I could bring myself to share in a literary work the wealth of impressions and personal details I’d accumulated in my head about America’s most celebrated black playwright. Writing this piece was very hard, because he was my friend and rather like a brother because we were born just three years apart, and grew up in the same cultural and racial worlds of the 50s and 60s. (The latest edition of my novel, Oxherding Tale, has a cover that August came up with, and he gets in the book credit for cover design and art.) I recommend that readers of this interview take a look at “Night Hawks” in Kenyon Review for the full story of our friendship.

I love that essay. I remember a moment when you talk about how August Wilson used to dream that after finishing his ten play cycle he would take a decade out of the spotlight. And how he’d emerge from that long span of seclusion like Eugene O’Neill did after his decade out of the public eye. What is it about the power of silence and isolation that can be so nourishing for one’s work?

I think every artist needs a quiet place where he can hear himself think without being constantly interrupted by others, by their needs and concerns. This is very much like needing to have a quiet, secluded place for the practice of meditation. Often during my life I’ve simply had to disengage from the social world in order to finish a project—like the month I spent in January, 1998 writing the twelve stories for Africans in America (later released as my third story collection, Soulcatcher and Other Stories). In our society we’re constantly bombarded by external stimuli—the phone ringing, the 3,000 product messages we’re exposed to daily and, of course, the needs of our spouses, children, family, friends and students. August simply wanted the uninterrupted time to think about and work on a novel he very much wanted to write, to create new plays not related to his ten-play cycle, to spend quality time with his wife and young daughter, and to sit on his porch reading a big stack of books he never had the time to get to since he was producing a play for the cycle every two years or so, seeing it through production, living away from home (Seattle) for months at a time, answering the questions of reporters, and doing public events of one kind or another. One has to “let go” these public exigencies in order to create. August and I talked about this problem—the constant “performance” pressure we lived with—all the time. To be honest, that’s one reason I retired from teaching last year after thirty-five years in the classroom. Just a day or two ago I read an interview by actor Linda Hamilton about her years of working with—and being married to—director James Cameron, and one statement she made stuck with me. She said Cameron once said anyone could be a husband or a father, but there were only five people in the world who could do what he does, and he was committed to pursuing that. Is this selfishness on his part? I don’t think so. In order to serve the art, which will become a gift to others (and the culture) perhaps for generations, an artist often has to just step away from the quotidian demands of public life and the social world.

I think every artist needs a quiet place where he can hear himself think without being constantly interrupted by others, by their needs and concerns. This is very much like needing to have a quiet, secluded place for the practice of meditation. Often during my life I’ve simply had to disengage from the social world in order to finish a project—like the month I spent in January, 1998 writing the twelve stories for Africans in America (later released as my third story collection, Soulcatcher and Other Stories). In our society we’re constantly bombarded by external stimuli—the phone ringing, the 3,000 product messages we’re exposed to daily and, of course, the needs of our spouses, children, family, friends and students. August simply wanted the uninterrupted time to think about and work on a novel he very much wanted to write, to create new plays not related to his ten-play cycle, to spend quality time with his wife and young daughter, and to sit on his porch reading a big stack of books he never had the time to get to since he was producing a play for the cycle every two years or so, seeing it through production, living away from home (Seattle) for months at a time, answering the questions of reporters, and doing public events of one kind or another. One has to “let go” these public exigencies in order to create. August and I talked about this problem—the constant “performance” pressure we lived with—all the time. To be honest, that’s one reason I retired from teaching last year after thirty-five years in the classroom. Just a day or two ago I read an interview by actor Linda Hamilton about her years of working with—and being married to—director James Cameron, and one statement she made stuck with me. She said Cameron once said anyone could be a husband or a father, but there were only five people in the world who could do what he does, and he was committed to pursuing that. Is this selfishness on his part? I don’t think so. In order to serve the art, which will become a gift to others (and the culture) perhaps for generations, an artist often has to just step away from the quotidian demands of public life and the social world.

In “Night Hawks” you talk about how you and August Wilson both had parents who were raised to value good manners, promise-keeping, personal sacrifice, loyalty to their own parents and kin, and a deep-rooted sense of decency. Do you ever find yourself disillusioned by new evidence of a loss of these values?

Yes, I’m very saddened by the erosion of those values in contemporary American society. I think about this every day, and this sea change will be dramatized front-and-center in my next novel.

There’s that moment toward the end of “Night Hawks” when you and August Wilson left the Broadway Grill, where you’d been talking for hours, and went to a nearby IHOP. As you sat at a table, you could feel the tension in the air, and then two guys stomped a third guy’s fingers and kicked his face to pulp. When the three of them fled, you looked around and noticed August was gone. His instincts from growing up in the Hill District of Pittsburgh kicked in, and he scrambled to an exit at the back of the restaurant. What advice would you give to writers who in their work want to address the violence they witness?

Be honest about it. That scene I described isn’t pretty. I just tried in the best journalistic fashion I could muster to put on the page with the greatest granularity of detail I could achieve what was given in perception to August and me in those brief, violent moments, unadulterated and uncensored. Later in this piece I venture an interpretation of what that violence means, or at least what it meant—as I see it—when you view it through the lens of our lives as black American male artists who grew up in the 50s and 60s.

In what ways did your friendship with August Wilson, a writer of your generation, anchor you as a writer? Have your friendships with writers significantly contributed to your life as a writer?

Except when we’re collaborating on projects with others, which I’ve done a lot of, the activity of writing is lonely, very solitary. That’s never bothered me because I was an only child and from kidhood learned to find ways to amuse myself for hours on end with no one else around. Nevertheless, sharing thoughts, feelings and experiences with another artist on a regular basis is refreshing. That person becomes like a mirror. Their experiences and practice can clarify and bring a subtler understanding to our life and creative practice. This is so because regardless of the discipline we’re talking about—writing fiction or plays, drawing, acting, etc.—there are commonalities at the core of the creative process and the creative imagination. (I would even extend this to the sciences and philosophy.) The other is always a helpful mirror for understanding ourselves better.

When I asked you this question three years ago, you said you wrote at night. Since my wife is pregnant and due in July, this question comes up for me a lot, and so I want to ask you to explain again how you managed to maintain a disciplined writing life while being a husband and father. If you were to write a manifesto on how best to generate new work and also fulfill one’s role as a parent, what would it say? Does generosity matter? Is there something powerful about the idea of serving?—serving one’s work, serving one’s family? Could it be that one’s various roles have an underlying unity?

Congratulations, Zach, to you and your wife! This is happy news. Regarding your question, I have to confess that in sixty-one years of living I’ve never taken a vacation. Not once. When not teaching, or doing speaking engagements, all my free time—summers, holidays, weekends, etc.—has been devoted to the dove-tailing creative projects I’ve had since I was an undergraduate, and to the things I love to study (Sanskrit, the logarithmic progress today of developments in the sciences, Buddhist sutras, and philosophy). Sometimes during the summer, I’d send my wife and kids off for a month of vacation with our relatives in the Midwest or South, and I’d stay in the empty house with the cat or dog, writing novels and screenplays. (They came to understand early on that sometimes Daddy is “here” physically but mentally is living somewhere else for a short period of time until he finishes the project(s) on his desk.) There have been more days than I care to remember when I taught or lectured, here or abroad, without going to bed the night before; nights when I suddenly and involuntarily burst into tears from total fatigue while working at three a.m. on some project with its deadline looming. My being a Buddhist has always helped. Thirty years of practicing meditation helps. When working, with my full concentration focused on an object (especially an imaginative one—a fiction, a drawing—as it takes shape in the world), I utterly forget myself and any personal concerns I might have at the moment. The illusory “self” disappears and there is only the present moment of doing, being completely absorbed, serving the work, which I know will financially serve my family’s needs, and ideally serve in the long run literary culture. It also helps, I guess, that I’ve been a martial-artist since I was nineteen-years-old and love to work out. My doctor told me last fall that I’m healthier than most men my age and I could live to be 100. In our home gym, I regularly get on the treadmill for 100 minutes, bench-press 240 pounds, review my old Choy Li Fut kung-fu sets (the fighting system friends and I taught for ten years at our studio here in Seattle in the 80s and 90s), do sets of twenty-five push-ups, etc. I like to turn on my I-Pod (filled with hours of soft jazz, anything with a saxophone in it) and sweat. Those hours in the gym are (for me) like a mini-vacation from the demands of the social world. So all these things flow together—mind, body, spirit—and reinforce each other in the realms of family, profession, and personal discipline. It also helps to remember something once said (I believe) by William James: “The essence of genius is knowing what to overlook.” I’ve always ignored everything that doesn’t relate directly to my family’s well-being and the particular work, creative and intellectual, that I was given to do in this life-time. If something doesn’t serve that, then it’s not on my radar screen.

You addressed slavery in Middle Passage and Oxherding Tale and its legacy of racism in Dreamer. How do you feel about the persistence of racism in our society, and whether or when or how it will ever end?

I don’t believe what we call “racism” will ever end. Racism is based on our belief in a division between Self and Other, and our tendency to measure ourselves against others (which is a natural thing, like looking at others and wondering, “How well am I doing?”), and to judge them as either better or worse than ourselves. Sad to say, it is also based on fear. This constant measuring of ourselves in a social context is something human beings will always do until they experience—as a Buddhist would say—awakening, which frees us from judging others or ourselves. And, in my humble opinion, it will be a very long time before all the billions of people on this earth awaken.

I don’t believe what we call “racism” will ever end. Racism is based on our belief in a division between Self and Other, and our tendency to measure ourselves against others (which is a natural thing, like looking at others and wondering, “How well am I doing?”), and to judge them as either better or worse than ourselves. Sad to say, it is also based on fear. This constant measuring of ourselves in a social context is something human beings will always do until they experience—as a Buddhist would say—awakening, which frees us from judging others or ourselves. And, in my humble opinion, it will be a very long time before all the billions of people on this earth awaken.

Would you be willing to share some of the lessons you learned from your parents and talk about how they felt about your career?

I always told my Dad, who died six years ago at age eighty-one, that he was the one who taught me how to work. Especially how to work unselfishly for the sake of one’s family—I remember back in the 60s when there was a time my father worked three jobs a week (construction during the day, as a night watchman in the evening, and helping an elderly white couple fix up their suburban home on the weekends). Seeing him work like that every day taught me that a person with a strong back and a good mind could accomplish anything he (or she) set out to do. My mother, who died in 1981, was the person in my family who gave me an appreciation for books, learning, and the beauty of art. They were always proud of me—their only child—and I never, ever, wanted to do anything with my life that would make them feel ashamed, because of all the sacrifices they made for me.

You mentioned earlier that you withdrew a book from publication, a novel that would have been your debut. Can you talk a bit about what you learned from writing six apprentice novels before Faith?

Those six “apprentice” novels, as I’ve always called them, taught me that a person who wishes to be a writer must write all the time. Every day. Even if only in your writer’s notebook or journal. They also taught me that 90% of good writing is revision. I’d write three drafts of those first six books, finishing one every ten weeks, but I hadn’t learned until I did Faith how to revise—that true revision is re-envisioning every sentence and paragraph, deepening and polishing them for music and meaning until no more revision is possible. And so I learned to generate pages. My ratio of throwaway pages to keep pages is often twenty-to-one. For Faith (written in nine months), I tossed out 1200 pages; for Oxherding Tale (written in five years) I tossed out 2400 pages; for Middle Passage (a six-year project), it was 3000 pages; and for Dreamer, more than 3,000 over the seven years I worked on that book. However, as Gardner mentioned to me in the early 70s, as the years—and decades—roll by, it becomes possible to write fast and with a high level of craft or professionalism because you no longer make the mistakes you made in your youth. Also because by the time I sit down to do a first draft of something, I’ve already composed in my head (or sketched out notes for) the opening sentence and thought a great deal about the movements in a piece. In other words, one of my cultivated, literary habits when I think is to revise a thought—playing with diction or word choice, and sentence structure—before I speak or put pen to paper. It’s just one of those habits you develop from writing for forty years and teaching for thirty-five

Those six “apprentice” novels, as I’ve always called them, taught me that a person who wishes to be a writer must write all the time. Every day. Even if only in your writer’s notebook or journal. They also taught me that 90% of good writing is revision. I’d write three drafts of those first six books, finishing one every ten weeks, but I hadn’t learned until I did Faith how to revise—that true revision is re-envisioning every sentence and paragraph, deepening and polishing them for music and meaning until no more revision is possible. And so I learned to generate pages. My ratio of throwaway pages to keep pages is often twenty-to-one. For Faith (written in nine months), I tossed out 1200 pages; for Oxherding Tale (written in five years) I tossed out 2400 pages; for Middle Passage (a six-year project), it was 3000 pages; and for Dreamer, more than 3,000 over the seven years I worked on that book. However, as Gardner mentioned to me in the early 70s, as the years—and decades—roll by, it becomes possible to write fast and with a high level of craft or professionalism because you no longer make the mistakes you made in your youth. Also because by the time I sit down to do a first draft of something, I’ve already composed in my head (or sketched out notes for) the opening sentence and thought a great deal about the movements in a piece. In other words, one of my cultivated, literary habits when I think is to revise a thought—playing with diction or word choice, and sentence structure—before I speak or put pen to paper. It’s just one of those habits you develop from writing for forty years and teaching for thirty-five

You mentioned earlier that your next novel will dramatize the erosion of values in contemporary American society. Can you say more about your inspiration for this novel?

My inspiration is the lack of civility and the disinterest in civilized living that I see every day around me in contemporary America, the lowering of personal and professional standards, the selfishness and violence and anger, and the absence of shared values in a country that has been culturally Balkanized for my entire adult life. I’ve been addressing these matters in my essays and articles for a decade now, especially the essays in Tricycle, Buddhadharma and Shambhala Sun. In the new philosophy book I co-authored with Michael Boylan the first story is my tale, “The Cynic,” narrated by Plato, which was originally published in Boston Review. He describes the moral collapse of Athens after the Peloponnesian War. What happened to the Athenians is, in my view, very much an analog for what we are seeing in America today. We have our ruthless people like Thrasymachus and Jason in Euripides’ Medea, our political leaders like the ones described by Thucydides (“Inferior intellects,” he wrote, “generally succeeded best”). And we certainly have our teachers at the universities (in the humanities) who are the spitting image of the Sophists.

Your book Philosophy: An Innovative Introduction: Fictive Narrative, Primary Texts, and Responsive Writing, which you coauthored with Michael Boylan, is coming out this month from Westview Press. From advance praise for the book, I gather it combines writing exercises with short fictions starring Plato, Kant, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Can you say more about this new book?

What I want to say is that from start to finish this is Michael Boylan’s book. He was inspired to put it together after reading a few of my short stories that have philosophers as protagonists (Plato, Descartes, the Buddha, Martin Luther King Jr.). But Boylan did all the work, all the heavy lifting in terms of pedagogy. He wrote six new stories of his own about traditional philosophers, but with my stories and his on Hannah Arendt and Iris Murdoch, he expanded the list of thinkers beyond what is in the usual philosophy textbook to include women and people of color, in the West and East. He wrote the introduction for each section; the study questions for both the stories and classic, primary texts; and provided the glossary at the front of the book and the “philosophy games” at the end. He explains the difference between direct, deductive presentations (philosophy), and indirect argument (fiction), and shows teachers how to get their students to write in both ways with intellectual rigor. Boylan is an outstanding educator. My contribution is minimal compared to his. But I have to add that this new book, my eighteenth, is an addition to my body of work (as well as to Boylan’s—he’s published over twenty books and ninety articles on philosophy and literature, as well as a novel of his own, The Extinction of Desire, for which I wrote an introduction) that makes me enormously happy. It should be very helpful to everyone interested in the relationship between philosophy and literature. Last week the publisher, Westview Press (they are Boylan’s regular publisher), sent me a lovely card that said, “We are tremendously proud of this book, as I hope you are, too.” Well, I am. And I’m in Michael Boylan’s debt forever.

What I want to say is that from start to finish this is Michael Boylan’s book. He was inspired to put it together after reading a few of my short stories that have philosophers as protagonists (Plato, Descartes, the Buddha, Martin Luther King Jr.). But Boylan did all the work, all the heavy lifting in terms of pedagogy. He wrote six new stories of his own about traditional philosophers, but with my stories and his on Hannah Arendt and Iris Murdoch, he expanded the list of thinkers beyond what is in the usual philosophy textbook to include women and people of color, in the West and East. He wrote the introduction for each section; the study questions for both the stories and classic, primary texts; and provided the glossary at the front of the book and the “philosophy games” at the end. He explains the difference between direct, deductive presentations (philosophy), and indirect argument (fiction), and shows teachers how to get their students to write in both ways with intellectual rigor. Boylan is an outstanding educator. My contribution is minimal compared to his. But I have to add that this new book, my eighteenth, is an addition to my body of work (as well as to Boylan’s—he’s published over twenty books and ninety articles on philosophy and literature, as well as a novel of his own, The Extinction of Desire, for which I wrote an introduction) that makes me enormously happy. It should be very helpful to everyone interested in the relationship between philosophy and literature. Last week the publisher, Westview Press (they are Boylan’s regular publisher), sent me a lovely card that said, “We are tremendously proud of this book, as I hope you are, too.” Well, I am. And I’m in Michael Boylan’s debt forever.

Thank you for your time and energy. May your work continue to unfold in ways that surprise and delight you. We look forward to reading more.

Thank you, Zach.

For Further Reading:

For more on Charles Johnson, including a bibliography, links to selected work, and a list of his top twenty books, please visit the author’s website.

For more on Charles Johnson, including a bibliography, links to selected work, and a list of his top twenty books, please visit the author’s website.

You can also read an essay by Johnson in the Summer 2008 issue of the American Scholar, entitled “The End of the Black American Narrative.”

Or read a 2009 article on “what you should expect from a worthwhile fiction workshop” that Johnson wrote for Writer’s Digest, entitled “A Boot Camp for Creative Writing (Uncut).”