Editor’s Note: For the first several months of 2022, we’ll be celebrating some of our favorite work from the last fourteen years in a series of “From the Archives” posts.

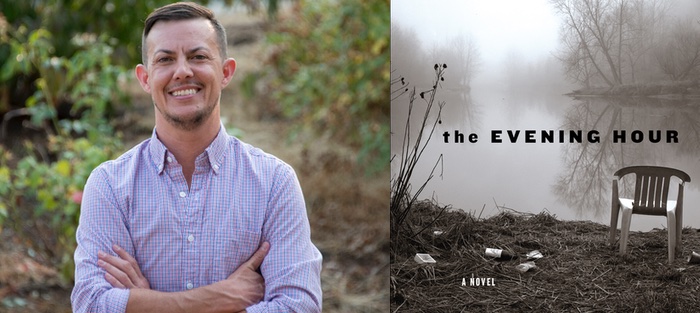

In today’s feature, Zachary Watterson talks with Carter Sickels about his debut novel, The Evening Hour. The interview was originally published on December 6, 2012. Sickels’s latest novel, The Prettiest Star, was published by Hub City Press in 2020.

Carter Sickels and I were drinking beers in a neighborhood bar in Seattle. We were a long way from the hills and hollers of Appalachia, but that’s where we traveled in our conversation about Sickels’s debut novel, The Evening Hour.

The Evening Hour, out earlier this year from Bloomsbury, is set in the fictive town of Dove Creek, West Virginia. Coal miners, Pentecostal preachers, and environmental activists populate its pages. It is the story of how mountaintop removal in West Virginia wreaked devastation on the inhabitants of Dove Creek, where the mountaintops are being blasted away by coal mining companies searching for new underground deposits. Sludge amasses and threatens to destroy everything that is familiar to Cole Freeman, who works as a nurse’s aid for the elderly and steals drugs and possessions from the people he is paid to care for. Mountaintop removal may lead to the deaths of many of the residents of Cole’s town. He sells OxyContin, Vicodin, Ritalin, Ecstasy, and Xanax, and some of what he sells he first steals from his elderly clients. Aside from the drugs and the biblical references peppered throughout the book—Cole’s grandfather is a preacher—there is a tension between homeowners in and around Dove Creek and the mining companies operating nearby.

The Evening Hour received strong reviews. It “is grounded in rich storytelling,” said Publishers Weekly. The Boston Globe found it “absorbing” and wrote that “Sickels manages to depict the region and its inhabitants vividly but without condescension.” Kirkus Review called it a “plainspoken novel, but one with intensely lyrical moments.”

Carter Sickels now lives in Portland, Oregon, after a decade in New York City and a stint at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, where he earned a master’s degree in folklore. Our conversation at the Seattle bar took place last April and continued over e-mails we exchanged in May 2012.

Interview

Zachary Watterson: In The Evening Hour you describe West Virginia in a way that made me feel connected to the land there. Far into the book, after the central disaster, a character named Blue Tiller tells Cole: “Do you know what we did when they started the strip-mining? We held them off by laying down in front of the bulldozers. A bunch of women. And illiterate men with shotguns. The police was always on the side of the coal companies, and they dragged us away like dogs. But we fought them tooth and nail.” Can you talk about the research you did in order to know this area and its people?

Carter Sickels: As someone who didn’t grow up in West Virginia, I didn’t have many of my own experiences to draw from, so I did conduct quite a bit of research while I was writing The Evening Hour. I read a lot of newspapers from the area, and oral histories. I read books about religion and about the coal companies. My grandparents and most of my family lived in southeast Ohio, in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, and I spent a lot of time there as a kid. And as an adult, I visited whenever I could. The culture and economic landscape of southeast Ohio is very similar to southwest West Virginia. A beautiful but ravaged part of the country.

There is a very particular brand of Christianity in those hills. How does poverty combine with the Pentecostal churches in your mind? Have these churches opposed the destruction of their communities?

I don’t know, honestly, about the connection of churches in the region and environmental activism. I’m sure there are churches that were or are supportive, but that never came up in my research. Probably that kind of activism, for the Pentecostals, would not be encouraged. Many people who live there feel a strong spiritual attachment to the land. They talk about the mountains and nature when they speak about God. In The Evening Hour, these are the moments where Cole feels the most connected to God. These are also the moments when his grandfather feels that way, too. West Virginians speak again and again of finding salvation in the mountains.

Cole Freeman is an idiosyncratic, flawed character—nurse’s aid, drug dealer, thief, grandson, and boyfriend. He steals from the people who trust and depend on him in the nursing home. How did Cole evolve?

Before I started writing the novel, I’d read an article in the New York Times about this young dealer who bought pills from old people in his town and then resold them to a younger crowd, and he stuck with me—how savvy and sharp he was. Not long after reading that article I wrote a scene that featured an aide in a nursing home who spoon-feeds oatmeal to a resident and then steals his money. That was the birth of The Evening Hour, and Cole Freeman, a nurse’s aide and drug dealer who, like the guy in the article, buys his supplies from old people. I wanted to have a protagonist who wasn’t heroic and who sometimes did things that were “bad,” or at least questionable.

Before I started writing the novel, I’d read an article in the New York Times about this young dealer who bought pills from old people in his town and then resold them to a younger crowd, and he stuck with me—how savvy and sharp he was. Not long after reading that article I wrote a scene that featured an aide in a nursing home who spoon-feeds oatmeal to a resident and then steals his money. That was the birth of The Evening Hour, and Cole Freeman, a nurse’s aide and drug dealer who, like the guy in the article, buys his supplies from old people. I wanted to have a protagonist who wasn’t heroic and who sometimes did things that were “bad,” or at least questionable.

Cole evolved into this complicated and sympathetic character. Yes, he’s buying drugs from the old people, and stealing from them, but he’s one of the few who talks to them and spends time with them, who genuinely cares about them. I think Cole wants out, not necessarily from where he lives, but the life he’s made for himself, and the history that weighs him down. He doesn’t know how to change or where to go or how to define himself, and that is a part of his struggle. He wants to make himself a better man and to reconcile his relationship with God, his grandfather, his mother.

Cole meanders through his life. Things start to shift with death of grandfather, and the arrival of Terry and his mother. Meeting Lacy also opens up his world in new ways.

Cole has many complex relationships—his girlfriend Lacy, his ex-girlfriend Charlotte, and Terry Rose, Cole’s oldest male friend, and the one with whom he has the most conflicted connection. Cole has slept with both men and women. How did you arrive at this element of Cole’s character and what is its significance in his journey?

You know, I can’t remember when I realized that Cole and Terry also had a sexual component to their relationship; I think it was probably after I’d been working on the novel for about a year. But once I figured that out, I felt like I understood Cole better, about why he felt so betrayed by Terry. Terry was the only person Cole felt close to when he was younger. Terry was accepting of Cole’s differences – his stutter, his family’s unconventional religion. Cole felt safe around Terry, and I think let himself be known, whereas he doesn’t show that kind of vulnerability with Charlotte, or even with Lacy. Terry was Cole’s first love, and so there is this part of Cole that feels nostalgic for the trust and closeness that they shared, which is much harder to find as an adult. When Terry chose to marry Karen, instead of running off with Cole, Cole felt abandoned, again, and he closed himself off.

For me, the crucial question isn’t so much about whether Cole is gay or not. With his upbringing and the environment he grew up in, it would have been impossible for him to identify as gay. Instead, the question is more about intimacy. There is a subtle homoerotic tension throughout the novel, not just with Terry, but also with Reese, who does live as an openly gay man, and even with Luke Cutter, the preacher. I wanted to show how there can be different kinds of tenderness between men, and to explore the fluidity of sexuality, the many different layers of intimacy.

Moving back to the subject of religion, did you attend services in a Pentecostal church during the time you were researching the book? And about snake handling, what is your impression of how often people are bitten?

I never went to a church that practices snake-handling. I hunted around a little bit, but I didn’t see any way to get access into that world. There aren’t very many of these churches, and they are not advertised. There is a fascinating documentary by Peter Adair, The Holy Ghost People, about a serpent-handling church. From the research I did, it seems like bites aren’t frequent, but it depends on how often people are handling. Recently, there was a pastor in West Virginia, Mark Wolford, who died after he was bit by a rattlesnake during a service. It is a fascinating world.

Further Links & Resources

- Read Sickels’s interview with the Lambda Literary Foundation, in which he talks more about writing gay characters from rural areas.

- Read Sickels’s essay on his first writing residency.

- Read Fiction Writers Review’s interviews with other Appalachia writers Pinckney Benedict, Josh Weil, and Mary Stewart Atwell.