Don’t use an outline. When you sit down to write, you shouldn’t know how a story ends.

This is the kind of writing advice that sent Josh Weil running from grad school in 2004 to a cabin in the Appalachian Mountains, a place he built from largely reclaimed materials with his father and brother.

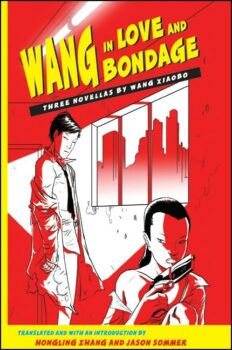

Like plenty of writers before him, Weil suffered under the weight of misdirected advice (or at least advice that was wrong for him) for a period of time before finally writing the book he wanted to write. His first collection, The New Valley (Grove Press, 2009), is comprised of three novellas connected and steeped in place—“the hardscrabble hill country” of Southwestern Virginia. There isn’t much light or casual in The New Valley. The world Weil paints in each novella is a hard one, where the living isn’t easy. A sense of yearning permeates these stories, though the characters themselves never can articulate what it is they’re searching for. As Geoffrey, the troubled narrator of the collection’s third novella explains, “Sometimes I look at everyone what comes to fill up their tank, and I think, Who do you miss? And, Who do you miss? And, Who do you miss?” Everyone misses someone in The New Valley.

Like plenty of writers before him, Weil suffered under the weight of misdirected advice (or at least advice that was wrong for him) for a period of time before finally writing the book he wanted to write. His first collection, The New Valley (Grove Press, 2009), is comprised of three novellas connected and steeped in place—“the hardscrabble hill country” of Southwestern Virginia. There isn’t much light or casual in The New Valley. The world Weil paints in each novella is a hard one, where the living isn’t easy. A sense of yearning permeates these stories, though the characters themselves never can articulate what it is they’re searching for. As Geoffrey, the troubled narrator of the collection’s third novella explains, “Sometimes I look at everyone what comes to fill up their tank, and I think, Who do you miss? And, Who do you miss? And, Who do you miss?” Everyone misses someone in The New Valley.

Weil was born in Roanoke, Virginia, to a family of would-be “back-to-the-landers.” His father is an agronomist and his mother is a woman “deeply attuned” to nature, so it comes as no surprise that Weil himself pays such careful attention to the natural world in his writing. The family traded Virginia for Malawi when Weil was a toddler but he returned to the Appalachian Mountains a decade later, at nineteen. Around that time, Weil worked with this father, brother and a local farmer to build that cabin—a place that’s made up of essentially a single, main living space and an attic space above for sleeping, though there’s a small side room, built to afford Weil’s stepmother some privacy when the family gathered together there. In that small room, Weil wrote the bulk of The New Valley.

Published in 2009, The New Valley was a New York Times Editors’ Choice selection. The book also won the Sue Kaufman Prize for First Fiction from The American Academy of Arts and Letters, the New Writers Award from the Great Lakes Colleges Association, and a “5 Under 35” Award from the National Book Foundation. Weil earned his MFA from Columbia University and has received a Fulbright grant and fellowships from the Bread Loaf and Sewanee Writers’ Conferences. He was the fall 2010 writer-in-residence at The James Merrill House in Stonington, Conn.

Interview

Is it true that you wrote all three novellas from the cabin?

All three. I wrote the first novella [“Ridge Weather”] when I’d just finished my first semester of grad school. I went down to the cabin to get away, because I was feeling pressured to move away from who I was. I threw away what I’d been working on at school and wrote the first draft of “Ridge Weather” in seven or eight days.

You said you felt “pressured to move away from who you were.” How so?

In grad school, you’re exposed to so much different work. There’s all of this excitement about experimenting—which is, actually, the right thing to be doing in grad school. To be honest, I hadn’t read a whole lot when I started grad school. Most of the students were enamored of things that were breaking the mold, pushing toward experimental fiction. There was an emphasis on stylistic experimentation. Those experiences did inform me as a writer, but eventually I came back to the guts of character and storytelling—and the musicality of language

Do you do most of your writing at the cabin?

I go there whenever I get time. It’s become my home base, as much as I have one. I was down there for seven or eight months when I was doing the final edit of The New Valley. It’s become a crutch. My friends make fun of me because I feel like I have to be down there, but there is something about that area. When I’m there, hiking up the ridge, I might hear a wild turkey or overhear the way people talk. Through that daily exposure, things click in my mind. A lot of people leave a place to write about it, but when I wrote about that place, I had to return to it.

Are you working on stories now set in Virginia/West Virginia?

My new novel is set in Russia … my mother’s family is from Russia. There are three places in the world that I love most: East Africa, Eastern Europe and Appalachia. That seems, on the surface, like an odd combination, but in each of these places there are pockets removed from the hell-bent progress of much of the rest of the world. They’re not backwards, but they are holding onto culture. There’s a sense of place in these places that we’re losing in much of America. If you’re in a strip mall, it feels pretty much like a strip mall.

That sense of place is important to you.

Yes. I have a friend down near the cabin named Russell. He’s eighty-eight. One of the first times I hung out with him, I asked him if he’d ever lived outside of the county. He turned around and pointed at this cot and said, “I was born right there.” His stories are all about place. They couldn’t take place anywhere else.

Yet despite this strong sense of being of a place, the protagonists in your novellas seem to be outside of a group, looking in. And you write from and about places that are not at the center of the world’s stage. Do you see that as a theme in your work?

I’m drawn to outsiders. My mom and dad have really strong personalities. They always seem a little outside of the norm. I feel the same way. My taste in music isn’t popular. Stuff I like in film isn’t popular. At a party, I’m the guy who corners people for a heart-to-heart when they just want to small talk and drink. I seem to be able to move between different worlds, maybe because I’m comfortable being uncomfortable, but there is something about the rawness of a place that appeals to me. Living out in the cabin, you strip away things and you find that it’s easy to live without them. I like the way my life moves through the day when I’m at the cabin. It’s not an easy life. I split my own wood and don’t see anyone for two or three weeks. I eat bad food. But that way of living can be easier on your character. It’s a pared down existence and it’s a cleaner, less cluttered existence. All these things that we have that we think make life easy — they might make life comfortable, but not easeful.

I’m drawn to outsiders. My mom and dad have really strong personalities. They always seem a little outside of the norm. I feel the same way. My taste in music isn’t popular. Stuff I like in film isn’t popular. At a party, I’m the guy who corners people for a heart-to-heart when they just want to small talk and drink. I seem to be able to move between different worlds, maybe because I’m comfortable being uncomfortable, but there is something about the rawness of a place that appeals to me. Living out in the cabin, you strip away things and you find that it’s easy to live without them. I like the way my life moves through the day when I’m at the cabin. It’s not an easy life. I split my own wood and don’t see anyone for two or three weeks. I eat bad food. But that way of living can be easier on your character. It’s a pared down existence and it’s a cleaner, less cluttered existence. All these things that we have that we think make life easy — they might make life comfortable, but not easeful.

Yet interestingly you sought an MFA at Columbia, in New York City, which seems the antithesis of this monastic existence. You’ve also attended writers conferences like Sewanee and Breadloaf. Is there another part of yourself that enjoys this side of the writing life? Or do you see it more as a career necessity?

It’s important for my writing to have that pared-down existence, but I also have this camaraderie with my writing friends. Those aspects of life are really important to me, too. I hardly ever write in New York. I can edit there, but the writing side of my life is at odds with New York. At Sewanee and Breadloaf, you recharge. You go to great lectures and classes and you’re up until 2 a.m. talking to brilliant writers, and then I can go off and be a crazy lonesome hermit.

Let’s back up a bit and talk about origins. How did you come to writing?

I started writing at twelve. I wrote a novel-length “thing” in high school and then screenplays. I read, too, but I wasn’t an English major or minor. I still read slowly. I have books that I absolutely love but, honestly, compared to other writers I know, I don’t read that many books.

That’s interesting. “Read a lot” is such common writing advice.

There are myriad kinds of writers but two big types, I think: people who are drawn to books and people who are drawn to telling stories. I didn’t come at writing through a love of reading. I always wanted to tell stories, whether it was through film or narrative photographs or painting. For me, it’s always been about wanting to tell the stories in my head.

Why did you decide to pursue an MFA?

I had been humbled in a way that life will humble you. I had finished a novel that didn’t go anywhere and realized I had a lot to learn. My personal life at the time had been shaken up, and school offered a certain safety and solidity—something to do for the next few years.

What was the best part of your program?

The other students. It’s a fantastic faculty at Columbia—fantastic people just dropping in, too, because of the program and the location. That was wonderful. But I was challenged by really talented students. I had to up my game to avoid embarrassment. Some of them are still my closest friends and closest readers.

How long did it take you to write the collection?

The first novella I wrote December of 2001. By 2006, I had finished the collection. In between that, I wrote stories and two novels, one that I ditched and one that I hope will work one day.

What was your writing life like then?

I would go down to the cabin when I was struggling or banging my head against the wall. I hoped the novellas would be published, but I wasn’t sure they ever would be. They were just things I wanted to write. One summer I wrote the first couple pages of “Sarverville Remains,” then I sat back down a year later, once I had the voice [of Geoffrey, the narrator]. It’s the most complex plot that I’ve ever written, because the story is told by a narrator whose understanding changes as he moves through the present action. I laid the story out scene by scene, kind of like an outline. I don’t like to call it an outline because people look down on outlines, but that’s how I did it. I wrote it in about two weeks.

Did you “hear” Geoffrey’s voice fully formed?

It sounds flaky but I did feel like he was telling the story.

Has that happened before?

Yes, but never like that. An image, something visual, usually kicks things off for me. “Stillman Wing” started with an image of an old guy floating in water at night, and my whole thing became about, “How do I get there?” In another novel, the one that I ditched, there was a character who, as a young boy, lost his virginity to an older woman in the back lot of gas station. I became interested in the woman he had sex with: “How did she get there?” That question led to “Sarverville Remains.”

So how important is revision to your process?

Revision for me often has to do with the length of the piece. The novel I’m working on now is in its fourth revision. It’s 600 pages. You can’t get something like that in one go. That said, I do believe that the heart of the piece is in the first draft. If the piece is going to work, I’ll know it in the first draft. Revisions can fix problems, but for me they can’t breathe life into it. Some writers can do that. I can’t.

The New Valley includes some of your own illustrations in “Stillman Wing.” Do you have a background in visual art?

My background is film and photography, but I used to draw a lot. I’ve put that aside. You can only focus on one thing in life that doesn’t pay. It was a blessing to make the book feel doubly my own through the illustrations. I knew I didn’t want chapter breaks or white space. I wanted something that was fluid in the way that time is. An image is not a hard stop. You see it and the meaning lingers on. I was struck by W.G. Sebald and the way he uses photographs and images, fusing the story with the present. That [approach] felt like it fit in [the character] Stillman’s mind

That’s very interesting. Have you ever thought of pursuing three-dimensional stories or “electric literature,” which utilizes hyperlinks and imagery and sound to “create” the work along with the text?

On the one hand, I should be interested in it. I’ve always been interested in visuals. That’s why I love films. On the other hand, I’m kind of a Luddite. I feel like the more you do that, the less it’s writing. You’re moving into a different medium. Right now, I’m not interested. Maybe that will change. I frankly would like to go back to filmmaking. I would like to write a screenplay in the next few years.

Back to people. I once heard Antonya Nelson say that she reframes the traditional question “What does a character want?” as “What does a character lack?” I’d like to talk to you about this idea of character desires—what they want, what they lack. How do you come at these ideas?

Some of the best advice I’ve heard is to find the wound in the character. That’s where the story is. Take Osby [the main character of “Ridge Weather”]. He feels his life has no impact. He’s deeply alone and impotent in his life. That’s a terrifying feeling. That’s his wound. But if he were able to articulate that fear, it would take the air out of the whole story. I don’t think people work that way. If people can identify their wound, they can usually heal it. I don’t want to imply that it should be to a very specific thing. If the wound becomes too exact or pinpointed, it can be claustrophobic in the story.

What’s the worst advice you’ve received?

I’ve heard a number of people say you should never know where you’re going, what the end is. That really damaged me for a while. Now I think, “How can you not know?” I can’t not think about it, have a sense of it, know what I’m shooting for. The interesting thing becomes, “How can I arrive there in an organic way?” And that, for me, means an outline. Sure, the greatest moments for me are when the story veers away from an outline, but I don’t think an outline hinders that; I think it makes those moments possible and still stay true to the core of the story. In MFA programs, people look down on outlines—as if only people writing pulp thrillers use them. Well, outlining is just the way my brain works.

Why do you think that is? Why do you think MFAs have that mystical approach? Does it somehow “reduce” art by rendering it in an outline? And if so, why?

I think the feeling is that an outline is imposed upon the story before you know what the story is and so it’s not growing organically; there’s something artificial about it. For me, at least, I disagree.

You’ve talked publicly, including at AWP 2010 in Denver, about the differences in form of the short story, the novella and the novel. Can you talk more now about those differences?

Generally, I think of a short story as a finely focused lens that looks at a small section of the world very intensely. A novel looks at a wide swath of the world with an inclusive kind of sweep. A novella can be the best of both worlds. It looks at a small part of the world but treats it with the generosity of the novel. The novella allows depth in its approach to the world and layers that are very hard to have in a short story. You have room for back-story. You have room for real attention to writing about the landscape. You have pacing that is more like a novel’s pace, pacing that allows you to sit with a character and love a character and not be booted out after twenty pages. To me, a major difference between a short story and a novella is that often a short story is starting with an idea or an image. It’s jumping off from that point and unraveling. A novella, for me, is going toward something. It’s built toward a conclusion.

Do you think of those differences in terms of structure?

Compared to the short story, the demands of narrative structure are greater on the novella and novel. Holding a reader’s interest for 300 pages is hard. A novel has so many strands running through it, and that relieves some of the pressure of the one strong narrative arc. The novella has the most pressure on the backbone of the narrative arc, because you don’t have the different strands but you do have the demands of the length.

You’re working on a novel now. Did you crave that longer form after The New Valley novellas?

Maybe. Again, the book I’m working on now is 600 pages, though it won’t be that long when I get it in shape. I like the swirl of the characters and thought and the way threads are drawn through. This new book feels more complex and unwieldy — unwieldy in a good way. I think that there’s a level of drama in plot that can feel too heavy-handed in a novella, but that works in a novel. I tend to think in a big expansive way — wanting to live with my characters and wanting to watch them grow.

Will you return to any of the novellas, to expand or continue them?

I hope I’ll return to Geoffrey and “Sarverville Remains.” I think with the other two novellas, their stories are complete. It may be ten years before I return to Geoffrey, but I’ve got notebooks and I’ve been scribbling thoughts about him.

What does your writing life look like now?

I’ve tried my damnedest to avoid working full time. I often go down to the cabin and live on cans of Campbell’s soup and split wood. I’m happiest in my life when I have a month to write twelve hours a day. Last summer I wrote 450 pages. I felt burned out after that but elated. That’s how I like to work. I don’t write every day. If I only have a half hour or an hour or two hours, I’d rather save it all up and write for a month straight. I’m always collecting things in my notebooks. It’ll be two years of thinking about some story often and then, at some point, things will click, I’ll collect all my notes and write.

Where are you with the new book now?

In a good place. My agent sat me down and we had a great talk; he had some helpful notes. (He also said it can’t be any longer.) It’s hard for me to know what to call a draft, but I’m hoping that this will be the last draft before an editor takes it. I feel like the book has found its shape and core. I don’t feel like I have overhauls to do anymore. At least I hope that’s the case.

As someone who seems to be no great lover of writers giving other writers advice, would you care to share some with new writers who are struggling to find their voices or subject matter?

Oh, I think advice from other writers is a wonderful, vital thing; it’s up to the listener to know what feels right for him or her and what doesn’t. Some of the most important ideas in my life came to me from other writers, including “Write what scares you.” If what you’re writing doesn’t scare you a little, it’s probably not worth writing. I’d add my own piece of advice, from my own experience: Write what you’re driven to write in the moment, no matter what people tell you is logical or smart or appropriate. Nobody told me to go off and write novellas. In fact, plenty of people would have warned me not to. And yet, lo and behold, that was the work I wanted to do, and so it was my best work, and it was what wound up, in the end, getting me published.