1. Video games aren’t about monsters, even when they are.

1. Video games aren’t about monsters, even when they are.

In a role-play game, or RPG, gameplay consists largely of traveling and fighting battles. Traveling, like the “free and easy wandering” of the Chang tzu, isn’t as easy as one might think—surviving monster attacks is usually the order of the day. Even so, traveling is one of my favorite things about RPGs because an RPG is a lengthy journey in a (hopefully) immersive world. My favorite game, Shadow of the Colossus, is difficult to place in a single game genre, but it’s more RPG than anything else. You wander an expansive landscape, soaking up the aesthetic splendor, gathering information, and eventually, finding and fighting colossal monsters. Monster-killing is central to the game, and yet this game is no more about monster-killing than gardening is about slaughtering aphids or Ender’s Game is about killing Buggers.

What sets Shadow of the Colossus apart from other RPGs is its successful elevation of monster-killing to near-spiritual levels. Monster-killing becomes, like Shiva’s austerities in the mountain cave, complex and meaningful. Most games require frequent monster fights as you travel, which creates a constant low level of anxiety. Shadow of the Colossus compresses this anxiety into 16 terrifying and epic boss battles. All monster-killing is inextricably linked to a game’s quest, which gives that violence a feeling of greater purpose. A quest is a concept to which we, almost because of the archaic resonance of the word alone, attribute the capacity for meaning. So the tasks that make up a quest, such as monster-killing as you travel, can start to share in that aura of significance as you play. This is powerful in Shadow of the Colossus but also present in games jam-packed with minor monsters.

I’ve probably killed thousands of beasts. I’ll spend 100 hours completing a game primarily consisting of monster fights. I’ll do this, and if a game is good, I’m as clean as a whistle at the end, not drenched in psychic gore or remorse. Monster-killing is a practical reality of most games; it’s best not to worry about or relish it too much. With monster-killing, as with practicing yoga postures, it helps to remember what it’s all for. It’s part of a quest for something meaningful, but monster-killing also relates to what, in RPGs, is often the main in-game activity: developing your character. Typically, higher levels of important characteristics, skills, etc. will accrue to your character as you complete battles. Your character (you) becomes a more multi-faceted, capable, and efficient being. Let’s call this self-cultivation via monster-killing. In my experience, games that lack self-cultivation feel a bit one-dimensional; I recently played Ms. Pac-Man (the super-speed kind, of course) and felt once again the frustration of playing a character that does not evolve.

So, monster-killing has to mean more than survival and more than self-cultivation and more than entertainment. For a game story to have legs, monsters must be able to be seen as signifying something, and killing them must also signify something. Monster-killing does not have to be a hypersigil; it’s more basic than that. The organizing moral principles of a game world often boil down to something desperately obvious: black-and-white, good and evil. This isn’t bad in itself because a good game, like a good book, then takes the player into a more familiar ambiguity. Good and bad become less easily separated and less relevant, in fact, the longer you travel. It’s sad when a game uses ambiguity itself to create interest, shifting the ground beneath our feet so frequently that we become bored and don’t even care when the true enemy is revealed to be our best friend. The trick is to create, in the gamer, a commitment to a point of view, whatever its morality—dramatic plot twists are never quite as devastating as they’re meant to be (unless the gamer or reader just hasn’t paid attention, which I admit can happen—my failure to anticipate the ending of Ender’s Game is a good example). No, I’d go for creating a creeping sense of doom, a teetering feeling, a worry—that’s how to get people. Never is this more elegantly done than in Shadow of the Colossus. The narrative is only ever suggested, but the gamer is completely committed to the events, even as your understanding of what is really going on gradually shifts and grows.

2. Choices.

In Shadow of the Colossus, you play a man alone in the Cursed Lands. Only a hint of context is given, no explanation for his arrival there with a dead woman in his arms. The man is essentially nameless, since we don’t learn it until the end. There are decrepit buildings throughout the Cursed Lands, clearly built by people now absent. The present occupants of the area are mostly lizards, turtles, fish, birds, and 16 Colossi, monsters that remain dormant until the man tracks them down and starts a fight. Each fight is absurd, terrifying in scale, a pesky fly of a man against a lumbering animated tower or a giant armored horse, until a glowing glyph is located somewhere on the Colossus and a sword thrust into it. Ribbons of black stream out of the monster and into the man after each kill. They seem to replace the light in the man, and his skin takes on ever-darkening tattoos that suggest, as they do on the Colossi, that something’s in there. What does all this mean? No official explanation has been made, but here’s one idea: he doesn’t realize it at first, but he doesn’t hesitate once he does realize—he’s sacrificing himself to bring his girl back to life. He’s trading his soul bit by bit for monster souls. The monster souls are actually smaller pieces of one larger entity, which, fully reunited in the man’s body at the end, ousts his soul.

So perhaps Shadow of the Colossus is, ultimately, a game about becoming a monster and setting evil free. All along, the man has been taking orders from a voice that emanates from a god-mouth in the roof of a crumbling temple filled with 16 Colossi idols. It could be humiliating to be such a toady, to be used so, but if it is, then we’re all a little pathetic, a bit tragic for our refusal to admit that we always serve something. In the end, the man appears to have agreed to trade his soul for his girl’s. She opens her eyes as he is finally subsumed. The interesting question is, At what point did the man agree to the trade? Did he just think all he had to do was take down a few monsters and he’d get his girl back? Did he know that he was reconstituting a force that would destroy him? You never get the sense that the man is gleeful or macho or even confident as he battles the Colossi; this is no God of War. If he isn’t informed about the particulars of his task, at the very least I think his sobriety suggests that he knows something serious is at hand.

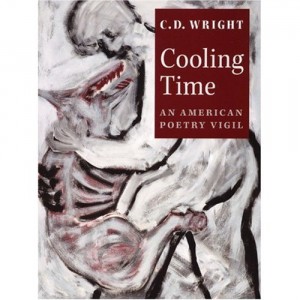

Overall, Shadow of the Colossus is a remarkably neutral game, and I enjoy the freedom to speculate about the story and the man’s state of mind. In Cooling Time: An American Poetry Vigil, C.D. Wright calls poetry a way of respecting the white space. That’s exactly how I love poetry and how I love Shadow of the Colossus. I feel invited to participate in forming the meaning of this game. The game has room for my experience of it. Perhaps this is why the prospect of a film version of Shadow of the Colossus terrifies me. I dread being told with such emphatic finality what the game is “really” about. There is another writer who has already said what I mean here: in Weight, Jeanette Winterson calls herself a writer “who believes in the power of story telling for its mythic and not its explanatory qualities.” The white space is where things are not explained and the reader or gamer is allowed in.

Overall, Shadow of the Colossus is a remarkably neutral game, and I enjoy the freedom to speculate about the story and the man’s state of mind. In Cooling Time: An American Poetry Vigil, C.D. Wright calls poetry a way of respecting the white space. That’s exactly how I love poetry and how I love Shadow of the Colossus. I feel invited to participate in forming the meaning of this game. The game has room for my experience of it. Perhaps this is why the prospect of a film version of Shadow of the Colossus terrifies me. I dread being told with such emphatic finality what the game is “really” about. There is another writer who has already said what I mean here: in Weight, Jeanette Winterson calls herself a writer “who believes in the power of story telling for its mythic and not its explanatory qualities.” The white space is where things are not explained and the reader or gamer is allowed in.

Honestly, most games do a poor job of respecting the white space. RPGs often give you either a distinctly “good” or “evil” character to play. In some RPGs, however, such as Oblivion: The Elder Scrolls and Fable 2, you can cultivate yourself in either direction. Americans, it turns out, prefer to play good characters. I toyed with murder in both games and had no stomach for it. (I guess that makes me an exemplary American.) That killing in video games can become objectionable could be either a feature of the high realism of many of today’s games or the possibility that we are now living in some kind of meta world, where everything is cleaner and less tangible than ever before and mostly originates in our minds. This is like living in a story. Today’s tenet is that killing is bad even in games. This is because we live in our heads so much, everything we do and value sometimes seems more abstract than ever before. We do not live in a real world anymore and war is too real for our refined palates. Our moral context therefore lets us object to play killing. At least, this is one way of seeing it. I find it interesting that at some points in time, it appears that a taste or talent for killing did not automatically disqualify a person from society. Knights did the dirty work to protect the more refined aspects of civilization, as embodied by the Ladies. This is the story, anyway. But Knights weren’t considered bad if they had to kill a beast or a beastly person—the Knights’ work was in service of the good and there was no moral quandary. But I think these stories live on and grab us today not because of their historical or literary merits but because we are fascinated by permitted murdering. Playing video games, then, becomes an exorcism of sorts—or a Tantric practice of excess meant to cure the obsession.

3. Hunting and not hunting.

Monster-killing is different, though. It’s funny how you can know yourself to be mostly, if not just ethnically, a pacifist—being raised by Mennonite-raised parents—and you then find yourself hunting. It’s digital hunting, but hunting nonetheless. There isn’t any blood, but there are grunts and sighs and other intriguing sound effects (praises to the sound engineers) as the beasts give up the ghosts and whatever treasure they carry. I’d argue that the realism of many games is what makes it so easy for observing non-gamers to connect real-world violence with game-violence and skip right over the critical thinking part. Was this a problem in the era of Jungle Pit and Space Invaders? No, I don’t recall anyone suggesting I not shoot at the alien-piloted ships encroaching on my personal space. (Now that was true exigency! That was do or die.) But just because I have to fight several vicious floating fish, mutated dinosaurs, and some Berserkers as I cross a desert in Final Fantasy 12 doesn’t mean I’m a killer. Someone once asked me, “Don’t you feel bad killing all those beautiful creatures?” It’s my pleasure to inform you that not only do I not feel bad, I enjoy it. I’m getting paid and collecting mad loot.

Yet, monster killing isn’t what any game or story is about. For me, Halo 3 is not so much about hacking through an endless onslaught of aliens and Flood; it’s almost entirely about the novelty, fun, and challenge of playing with a partner (I find the enemies’ comments hilarious, too—something about their tone). Shadow of the Colossus is not so much about finding and fighting large beasts. While I did spend most of the game feeling terrified, I’ve got some sweet memories, too. The Cursed Lands are vast and still. A small breeze blows. Sun light is dappled under the trees, brilliant over the oceans, and it turns the crumbling stone shrines and plazas a soft platinum. A melancholy music plays during battles; otherwise, it’s mostly environmental sounds: water, wind, Agro’s hooves on the ground. I can hear these now. But what stays with me the most is the image of the woman’s body lying in the temple, diffusing the sun with her white dress, the doves shifting around her, the man and his horse simply watching. A few feet from an aisle of menacing Colossus idols, the tender scene becomes sublime. Without the weight of words, it speaks of the frailty of the living, the uncertainty of our tasks, and the ache of love. It is mythic. It moves me.

Yet, monster killing isn’t what any game or story is about. For me, Halo 3 is not so much about hacking through an endless onslaught of aliens and Flood; it’s almost entirely about the novelty, fun, and challenge of playing with a partner (I find the enemies’ comments hilarious, too—something about their tone). Shadow of the Colossus is not so much about finding and fighting large beasts. While I did spend most of the game feeling terrified, I’ve got some sweet memories, too. The Cursed Lands are vast and still. A small breeze blows. Sun light is dappled under the trees, brilliant over the oceans, and it turns the crumbling stone shrines and plazas a soft platinum. A melancholy music plays during battles; otherwise, it’s mostly environmental sounds: water, wind, Agro’s hooves on the ground. I can hear these now. But what stays with me the most is the image of the woman’s body lying in the temple, diffusing the sun with her white dress, the doves shifting around her, the man and his horse simply watching. A few feet from an aisle of menacing Colossus idols, the tender scene becomes sublime. Without the weight of words, it speaks of the frailty of the living, the uncertainty of our tasks, and the ache of love. It is mythic. It moves me.

4. The Path and the Glimpse.

But even in a gorgeous world, monsters are not just a distraction from these emotional treats. They are not just for killing either. Monsters could be the Path itself, the path to the end of suffering, a path worth walking on, that gives sense of direction and purpose to life. A holy man tries to walk toward God, away from the world. Other holy men try to help others find the path. Sometimes I wonder if I think by completing tasks I’ll be enlightened. Sometimes I look at the end of my various efforts for a face shining behind the veil and I wonder if I’m conflating worship and task-completion. I’m knocking and knocking at the door, completing side-quests, collecting Nirnroots, rolling a katamari out of fireflies… Who waits on the other side of these doors? Does he even want what I am bringing to him? Is it even good?

I know a physicist who would chuckle at my dilemma. This man goes from A to B. Granted, his B is fusion energy, a true “creative sort” kind of vision, and the path between his A and B is far from dull. The important thing for him is to get there. Going from A to B—having a clear question and methodically answering it—in the rest of life oftentimes is dull. There is no room for wondering or wandering and asking what about C? When I think about what it is that makes playing RPGs interesting to me, it’s not the A to B. That, in fact, is what makes them boring. There are no real stakes involved. If there were real stakes, a real possibility of closing an Oblivion gate and preserving humanity to flail poignantly another day, I might value basic A to B a bit more. I might reject my own formulation of monster-fighting as self-cultivation and call it critical training. But I prefer to live and play in worlds where self-cultivation, the cultivation of life, and the search for something divine are respected options. Consider: in our world, gardeners are usually respected and admired. They may cultivate the most arcane or common of life forms. They may grow things in apparent disarray or in the strictest regiments. In truth, they spend more time spreading silica to lacerate slugs’ soft bodies, unleashing plagues of ladybugs upon the aphids, and drowning Japanese beetles in jars of soapy water than anyone ever knows. But no one would diminish gardeners’ work as mere beetle-killing.

Ask why not and someone might say, “Because gardens are beautiful.” Ah, beauty. The ultimate excuse and the ultimate end goal. The trump card. Beauty is God. Sometimes people will use God as a trump card, but that’s just too obvious. God is unknowable. God is barely perceivable. Beauty is often attributed to God. What people who invoke either are really trying to do, I suspect, is indicate that something beyond us has been Glimpsed.

Can monster-killing cause a Glimpse? Perhaps. The figure of the Death-seeker is a warrior who does his warrior duty, but more than anything hopes to be killed himself one day, never is, battles on, and inadvertently becomes a better warrior, better than everyone else, his skills ascend beyond known levels, and to those who worship that sort of skill he gives the Glimpse. They call his killing beautiful, they call it God-given. For him, monster-killing was to be his path out of here, but like some kind of bitter Bodhisattva, his field of compassion is the field of blood and blade. The Death-seeker is like Arjuna. He does not want to fight, but God says Fighting is Your Duty, it is your duty to fight because that action keeps the world in balance. The hero Beowulf also has a duty to fight. The poem Beowulf is not about battling horrendous monsters—it’s about keeping the world going, about following a code of behavior upon which life depends and derives its structure, its meaning, and its perpetuity. Without a hero to keep monsters away from the good people, all would be chaos and death. Power protects the people, and, as in Seamus Heaney’s translation of Beowulf, “Behavior that’s admired/is the path to power among people everywhere.”

Can monster-killing cause a Glimpse? Perhaps. The figure of the Death-seeker is a warrior who does his warrior duty, but more than anything hopes to be killed himself one day, never is, battles on, and inadvertently becomes a better warrior, better than everyone else, his skills ascend beyond known levels, and to those who worship that sort of skill he gives the Glimpse. They call his killing beautiful, they call it God-given. For him, monster-killing was to be his path out of here, but like some kind of bitter Bodhisattva, his field of compassion is the field of blood and blade. The Death-seeker is like Arjuna. He does not want to fight, but God says Fighting is Your Duty, it is your duty to fight because that action keeps the world in balance. The hero Beowulf also has a duty to fight. The poem Beowulf is not about battling horrendous monsters—it’s about keeping the world going, about following a code of behavior upon which life depends and derives its structure, its meaning, and its perpetuity. Without a hero to keep monsters away from the good people, all would be chaos and death. Power protects the people, and, as in Seamus Heaney’s translation of Beowulf, “Behavior that’s admired/is the path to power among people everywhere.”

5. The qualities of a monster.

Which brings me to Ender’s Game, by Orson Scott Card, and the question of what a monster really is. Like the monsters of Beowulf, the Buggers are known to be remorseless, inhuman outsiders with whom humans cannot communicate. When you can’t communicate with something, the obvious course is to fight it, right? So humans and Buggers fight. The book is the story of Ender, a super-sensitive, super-intelligent child trained from age six to lead Earth’s armies against the Buggers. Throughout the entire book, Ender is kept busy trying to survive against a wide range of more immediate threats to his survival—his violent brother, his unforgiving training program, his loneliness and isolation, his terror about becoming a monster himself. Always a new enemy for poor Ender. He is kept so busy trying keep his head on straight that he never has a minute to question the assumption driving everything—that the Buggers are monsters—and the first time I read the book I was so tangled in Ender’s daily life that the story’s denouement practically gutted me. To learn that the child-genius battle commander Ender has been tricked into wiping out the bugger race, and to witness his grief and remorse as he learns the truth about the Buggers—it was just too much. Turns out the Buggers were, more or less, everything a monster should be—hideous, aggressive, and incomprehensible—except an actual threat to humanity. From the beginning, Ender’s reward for protecting humanity from the Buggers would be freedom from terror, as well as honor and glory, but in the end, in return for killing the Buggers, Ender is not free and is not honored. Ender is used, as the man in Shadow of the Colossus is, by a powerful and detail-withholding force.

Withholding details—in other words, failing to communicate well—is a sign of a monster. Those who use the child Ender are monstrous in their treatment of him, whatever their motivation. The Dormin, as the disembodied power in Shadow of the Colossus calls itself, speaks cryptically in a strange language; even without form, a more disturbing monster I’ve seldom encountered. I wish game designers would remember that giving monsters casual speech sort of neuters them. A monster is not for chitchat. A boss monster bloviating on its plans to kill you is comedic, not scary. Better to make the bosses unforthcoming, otherworldly, and alien. Especially since so many games promote the value of self-cultivation. In the game, your goal is to cultivate yourself into the ultimate of what you are (human, elf, whatever), the fullest expression of your potential, and why shouldn’t this include communication skills? Sometimes it does: the Speechcraft skill in Oblivion perfectly fills this need. The more pleasantly and effectively you can communicate with townspeople, the higher your Speechcraft level. Among the many typical skills your character must develop, including weapon and armor skills, fighting skills, strength, endurance, magic, etc., Speechcraft is what truly separates you from thugs and monsters.

Withholding details—in other words, failing to communicate well—is a sign of a monster. Those who use the child Ender are monstrous in their treatment of him, whatever their motivation. The Dormin, as the disembodied power in Shadow of the Colossus calls itself, speaks cryptically in a strange language; even without form, a more disturbing monster I’ve seldom encountered. I wish game designers would remember that giving monsters casual speech sort of neuters them. A monster is not for chitchat. A boss monster bloviating on its plans to kill you is comedic, not scary. Better to make the bosses unforthcoming, otherworldly, and alien. Especially since so many games promote the value of self-cultivation. In the game, your goal is to cultivate yourself into the ultimate of what you are (human, elf, whatever), the fullest expression of your potential, and why shouldn’t this include communication skills? Sometimes it does: the Speechcraft skill in Oblivion perfectly fills this need. The more pleasantly and effectively you can communicate with townspeople, the higher your Speechcraft level. Among the many typical skills your character must develop, including weapon and armor skills, fighting skills, strength, endurance, magic, etc., Speechcraft is what truly separates you from thugs and monsters.

Self-cultivation is the process of becoming good at things. It is also the process of becoming “good” in the game’s moral universe. All of us like being good, or at least knowing how to be bad. But let’s put that aside. There are some terribly beautiful games out there, and they really aren’t about good and bad, self-cultivation, or monster-killing. They offer a way to transcend necessity and ambition: deep appreciation, which is deep observation, a meditative state. A game can be played like this—Shadow of the Colossus allows it, but few others do, in my experience. I admit I indulge myself in this way of playing. I look for it. A game so perfectly rendered and self-contained, that requires so little compromise from my imagination—maybe it’s just me, but just being in this kind of game world is itself the desired outcome. It’s the good result, as the surgeons say. It’s the end of yoga practice, as the yogis say, when you don’t have to practice anymore because you have achieved enlightenment and now you can just lounge in the temple garden and leave the monster-killing to the noobs.

6. Postscript.

That, in part, is what monsters are for. Of course, monsters mostly just want to kill you. So there’s great risk. But isn’t there always? With great risk we are born. With great risk we love. With great risk we read books, listen to music, and play video games. It would seem that we cannot help but run around naked everywhere with our hearts hanging out. And then there are those monsters we fling ourselves against over and over until we get better, know more, can put our legs behind our head, or die. We need game monsters, since sometimes life’s monsters are just too arbitrary, too, well, monstrous; it matters to be able to accomplish something, even if only in a game. That could be why we invent our gods, couldn’t it? So we can suffer a little less.