I recently tried on a virtual reality headset, which simulated the experience of visiting a house. Despite hype and hoopla, I found it disappointing—more like walking through a diorama than being in an actual home. For me as a writer—a zealous, re-born writer—electronic make-believe pales in comparison to opening the door of memory and dreams. The door which is, as William Maxwell says in So Long, See You Tomorrow, “standing open permanently,” even if sometimes we cannot find it, or only stumble through by chance. That was true for me. I’d always remembered and dreamed, but hadn’t written fiction for decades until a confluence of world and personal events pushed me through the open door of memory.

Even before I could read or write, I kept a journal of sorts. My parents prompted me with a question after the bedtime story, and took down my dictation: What was the best or worst thing that happened today? The nightly ritual formed a habit of documenting experience, of putting joy and sorrow into words on the page. I wrote and read my way through school. But as Wallace Stegner says in Crossing to Safety, it’s hard to take notes when you’re going over Niagara Falls in a barrel. Navigating the cataracts of work as a psychotherapist and family life with three children and aging parents, I didn’t fictionalize for many years except—mea culpa—in that dreaded genre, The Christmas Letter.

But life has chapters and volumes. One narrative arc touches down, a new one begins. On 9/11 the twin towers fell. Soon after, my parents—twin towers of my life—died. These events punctured and punctuated my illusion of continuity, of infinitely renewable time. In the unsettled period that followed, I often retreated from the Washington suburbs to the Pennsylvania farmhouse my parents had chosen as our vacation home during another turbulent time: 1968. The Shanksville meadow where Flight 93 went down is not far away, but I found quiet and tranquility up on the ridge.

But life has chapters and volumes. One narrative arc touches down, a new one begins. On 9/11 the twin towers fell. Soon after, my parents—twin towers of my life—died. These events punctured and punctuated my illusion of continuity, of infinitely renewable time. In the unsettled period that followed, I often retreated from the Washington suburbs to the Pennsylvania farmhouse my parents had chosen as our vacation home during another turbulent time: 1968. The Shanksville meadow where Flight 93 went down is not far away, but I found quiet and tranquility up on the ridge.

Sometimes at night I would wake and see my father’s reading light shining along the corridor—on its automatic timer, an informal security system for when the house stands empty. Dad was an insomniac; it seemed he still lay awake, reading a dog-eared paperback mystery.

Drifting back to sleep, I almost heard him reading to me from Crockett Johnson’s classic picture book Harold and the Purple Crayon. Remember how Harold draws his way home, lighting his path through the dark with the moon he sketches? Well, in the early morning hours, I picked up my own long neglected purple crayon and began to write stories again, writing my way through Maxwell’s eternally open door. I rediscovered the territory of Keats’s Endymion, “the space made for the soul to wander in and trace its own existence,” the inner space of the creative process.

On writing breaks, I climbed to the attic and pored over family papers like Dad’s letters and v-mails to my mother from the wartime winter of 1944-45—cryptic loving messages to his then fiancé. She’d saved them, pressed flat, tied with ribbon. But where were her letters to him? Lost somewhere in Europe, as he almost was.

Other times, I walked through the fields, into the woods, and along the creek bed to gather rocks and fossils. My great aunt, a farm girl from Tennessee who became a historian, had exhorted me to study geology, the history of the world. I never did take her advice, but arranging fossils on the deep windowsills, I realized writing is like a geological process: tumbling shards found in the frost-heaved fields of memory, occasionally pressing ashes into diamonds, if we’re lucky.

During hunting season it’s not so safe to walk in our woods. So that year I explored the grounds of a deserted resort hotel nearby. For over two centuries The Bedford Springs was a renowned spa, it had declined and finally closed in 1985 after a flood raced through its narrow valley. Intrigued by the crumbling ruin, I visited the Bedford County Historical Society and skimmed backward through years of clippings from the local paper. A headline from July, 1945, jumped off the page. Had I been hunting for a story? Well, the story captured me.

“Japs to Be Housed At Springs Called Blue Chips of War.”

I learned that in the final weeks of World War II, the Hotel had been the unlikely detainment site for the Japanese Ambassador to Germany, his staff and their families, captured fleeing the fall of Berlin. The State Department anticipated using them as valuable bargaining collateral for American POW’s. The Springs was deemed the perfect detainment site—empty and capacious, isolated but accessible to Washington. Although housing enemy aliens at the resort as the bitter war continued in the Pacific Theater was anathema to the hard-pressed local community, the State Department prevailed, promising spare conditions for the prisoners and jobs.

The brief newspaper accounts of the unwelcome prisoners’ arrival made passing reference to a few European women married to Japanese diplomats—and their mixed race children. How doubly, triply alien those particular families must have seemed to the rural area’s residents. The additionally complicated dilemma for these Japanese-European families among the detainees, the special poignancy of the situation for children, lured me on. I continued research at The National Archives, winnowing through boxes of documents, lingering over the passenger manifest for the ship that brought the detainees to Ellis Island.

I’d fallen in love with an idea for a story, but like falling in love, the beginning is the easy part. My coup de foudre was all very well, but to sustain the initial spark for a novel required work—tedious as well as exciting. Fortunately, I discovered I loved the mysterious process of writing in a longer form as I wrote draft after draft, year after year. I told the evolving story from many points of view until one voice demanded to take over: Hazel, a young local woman working at the hotel while she awaits news of her husband who is missing in action in the Pacific Theater. Only upon finishing the final draft did I understand why it had to be Hazel—she speaks for my young mother and all the waiting, fearful women, their missing letters and silent voices.

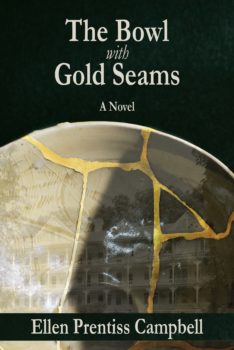

You see the beloved everywhere, when you’re in love. And I was reminded of the project everywhere. Once on a chance museum visit to the Sackler Gallery in Washington, I happened into an exhibit of ancient Japanese kintsugi, a type of pottery I was unfamiliar with. In kintsugi, broken porcelain is intentionally mended with contrasting golden glue. The very visible seams, the scars of damage, become enhancement. Brokenness is made beautiful, the Japanese say. A kintsugi bowl became an integral part of my novel’s plot, as well as an over-arching metaphor for the novel’s theme of life’s damage and mending; the possibility of beauty even in brokeness. The bowl gave the novel its title, The Bowl with Gold Seams, and its cover illustration of a kintsugi bowl with a faint image of the hotel floating inside.

You see the beloved everywhere, when you’re in love. And I was reminded of the project everywhere. Once on a chance museum visit to the Sackler Gallery in Washington, I happened into an exhibit of ancient Japanese kintsugi, a type of pottery I was unfamiliar with. In kintsugi, broken porcelain is intentionally mended with contrasting golden glue. The very visible seams, the scars of damage, become enhancement. Brokenness is made beautiful, the Japanese say. A kintsugi bowl became an integral part of my novel’s plot, as well as an over-arching metaphor for the novel’s theme of life’s damage and mending; the possibility of beauty even in brokeness. The bowl gave the novel its title, The Bowl with Gold Seams, and its cover illustration of a kintsugi bowl with a faint image of the hotel floating inside.

In an uncanny parallel process, as I wrote, the derelict hotel was purchased and restored. The enormous, rambling building’s damage was mended in less time than required to complete and publish my novel. Before the book was finished, before I even knew it would ever be between covers, I stayed at The Bedford Springs. Crossing the same real threshold my imagined characters had, entering the open door of memory and dreams, I saw “my people” everywhere; disappearing around corners, down the balcony in flashes of kimono, white waitress aprons, guard uniforms.

The book is launched and out in the world; the hotel is once again a thriving resort. So those two parallel narrative arcs are complete. A third arc continues: my re-discovered writing life. I’m working on my second novel, piecing together more fragments of lived and imagined experience, attempting to fuse the shards into a fresh narrative whole with the golden glue of the creative process. Writing is kintsugi on the page. And when I talk about the book with readers, the motif of the broken and mended bowl resonates in our conversations, over and over again. The art of kintsugi is perhaps not so different from the act of coming to terms with loss poet Elizabeth Bishop writes of in One Art. If writing is kintsugi on the page, kintsugi is the art of losing.