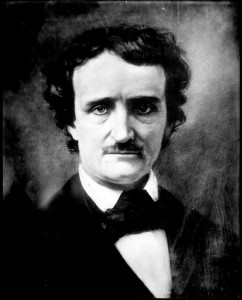

“Were I called on to define, very briefly, the term Art, I should call it ‘the reproduction of what the Senses perceive in Nature through the veil of the soul.’”– Edgar Allan Poe

When I was sixteen, my heroes were three: Jim Morrison of The Doors, Charles Baudelaire, and Edgar Allan Poe—rebels all! Cooler than James Dean, prematurely dead from desperate, drugged out living, and word men to the bone. By the time I reached eighteen, two realizations changed the composition of this pantheon. I couldn’t get into hard drugs, which meant I’d never be Morrison. I couldn’t commit to calling myself as a poet, which meant I’d never be Baudelaire.

That left Mr. Poe, an opium-drenched (or so I thought then—most biographers doubt it) macabre romantic, as the sole object of my teenage aspirations. He was prodigious and uninhibited, and he wrote in a variegated American vernacular that gave free voice to whatever characters he could imagine. And Poe had an even stronger lure for my hyperactive, paranoid teenage mind: the “hypnagogic state” between sleep and waking, which he cultivated. I therefore duly cultivated hypnagogia myself, mining it almost exclusively as the source material of my teenage scribblings.

In the hypnagogic vision, all is permitted. It was better than drugs, I reasoned then, because it represented pure imagination without the opium haze of Baudelaire or the LSD haze of Morrison. My hypnagogic visions belonged to me alone, and I felt proud to have created them without chemical influence. So I followed Mr. Poe through the hypnagogic door to the best of my abilities, and used my visions to produce a ghastly stream of first-person fantasy anecdotes that I, through high school and my first year of college, confused with literature.

It took awhile to realize that this element of pure imagination, while necessary to the creation of literature, was not sufficient for it. Everything I wrote in the hypnagogic mode lacked an inner tension, but I couldn’t put my finger on the missing element. There to bail me out was Mr. Poe, who proved himself an astute and able mentor; as I reread him, he taught me that one needs more than a stream of images—regardless of how deep in the self they may spring—to tie a story together. Hearing a man tell his tale blow by blow does not create drama. But hearing that same man tell his tale when he believes that it carries a different meaning than we, as readers, see in it—aha! Then we have what Faulkner called the human heart in conflict with itself, expressed in the classic Poe conundrum of the unreliable narrator.

I had heard the term “unreliable narrator” in high school—heard of it as one hears of a literary technique or tool, like foreshadowing or the second-person voice. But a closer look at Poe’s 1835 story “Berenice,” one of my first favorites, convinced me that the unreliable narrator was not simply a clever authorial device, but a way to approach the very creation of literature. Through this story I wound my way to the first of the five simple writing lessons that I learned from Poe, and have continually relearned at the cost of endless rewrites, false starts, and abandonments.

Lesson #1: Dwell in the space of dissonance between who your characters are and who they tell the world they are, for this is the root of personal drama.

“Convinced myself, I seek not to convince,” the narrator of “Berenice” tells us early on in his story. This character, like many of Poe’s, is embroiled in a fundamental delusion; Poe does not announce that delusion, but allows us to gradually see the gaps in the narrator’s thinking that eventually convince us of his unreliability and madness. In most successful first person literature, we are unable to see the narrator’s delusion until we have gotten to know and trust that narrator. What’s the joy of hearing the tale of an insane person when we know, from the beginning, the precise contours of her insanity? What fun is it to hear that tale when she knows those contours as well? Would we not vastly rather hear the tale of a character who does not truly know herself? A character who—like most of us, if we’re honest—creates a seamless and continually-readjusting narrative of her own life that may bear no resemblance to the life that she actually lives? Writers who explore the dissonance between self and the narrative of self should credit Poe, who sailed into it and charted it for us.

Lesson #2: Get beyond the “write what you know” adage.

This hackneyed phrase is a dangerous teaspoonful of pabulum dispensed all too frequently to young writers. Poe’s “Mesmeric Revelation” (1844), “Some Words with a Mummy,” and “The Power of Words” (both 1845) all feature characters whose relationships with the human realm are tenuous at best; writing stories based on them reflected Poe’s prodigious faith in his own muse. Writing “what we know” is a by-product of the fiction experience, not a prerequisite for it; we write, naturally and without choice in the matter, from our own experience (whether real or imaginary). To further limit ourselves by writing what we consciously know leads us into self-referential loops that deny us the greatest gift we have as writers: our imaginations. Instead of writing what we know, we ought to keep writing what we don’t know until, eventually, we begin to comprehend it. If we are unlucky or false to our muse, the result is gibberish; if we are assiduous, truthful to our muse, and lucky, then the process of our coming to understand our imagined worlds is mirrored in our writing. Rather than tell us to write “what we know,” I suspect that Poe would have told us to freely give flesh to anything we imagine, regardless of how we fear it or don’t know it when we begin writing. The words we use to discover it can then leave behind a map to help our readers discover it as well.

Lesson #3: Vary who you write about.

Lesson #3: Vary who you write about.

The high and the low in life both have their own equally poignant dramas. Roderick Usher (from “The Fall of the House of Usher”) and William Wilson probably represent Poe’s two most realized blue-bloods—too erudite for their own good, cultured to the point of insane sensitivity, and so mired in their lofty thoughts that the shapes and textures of the world have lost their meaning. Contrast them with the characters of “King Pest” and “Why the Little Frenchman Wears his Arm in a Sling,” neither of whom appear to have ever let a thought loft more than an inch beyond their skins. If we limit ourselves to a too-narrow character range, we limit ourselves to one kind of inquiry; but even when we know this, the temptation to settle into a certain kind of character often requires a conscious effort to resist. Writers who wish to give Mr. Poe his due would avoid this pitfall by plowing more than one valley of the human mind—even if self-imposed force is required to lift one’s plow from the earth and explore fresh ground.

Lesson #4: Write characters who are not only wrestling with moral dilemmas, but characters who have wrestled with these dilemmas and realized—alas, too late—that they have lost their match.

These characters, usually haunted by an event in the distant past, are rife in Poe’s work for good reason. They are more interesting to write because their moral dilemmas are cumulative, as is their reward for perseverance or (more likely in Poe) their comeuppance for continued moral failure. Once the wrestling match is over, then life gets more interesting: the characters must live with themselves, shaping their lives around their rage, fear, or shame the way a young tree grows around a spike or a dog learns to walk with three legs. People can live for decades after the most tragic or decisive moment of their lives, and in that gap of time—reflecting on the past, graced by it, stalked by it, trying to overcome it—their characters truly take shape. It is one thing as a writer to discover innocent characters whose lives are torn to shreds by circumstance; it is quite another to discover characters whose relationship to their own pasts continuously propels them into a fresh perils of their own devise.

Lesson #5: Make the imagined world your characters live in feel as alive as possible, not simply to replicate reality but to render the soul.

The classic example of this idea in Poe is the literal, physical house of Usher. In this tale Poe uses the phrase “the sentience of all vegetable things” to describe the living-ness of physical location; the lushly-described schoolhouse in “William Wilson” is another example. Here Poe taps into the physicality of the world—what the Senses perceive in Nature—that writers who give any nod at all to reality must not forget. Such aliveness is easy to see manifested on the page of a successful completed work, but harder to see when we are mired in a work that may or may not come to fruition. Seeing it as we write requires not just patience and attention to sensory detail, but a faith in this “sentience of all vegetable things”—a faith in the living-ness of one’s imagined world. Without this faith, no amount of sensory detail will resonate with an audience; for lack of it, even the most exquisitely-described setting or experience will fall flat on the page.

If we want our readers to experience the world as we describe it, we must hone our abilities to feel this world as alive and write it as alive. The thickness of the air of our setting, the texture of its walls, the dirt on its floor, the scent of its passers-by…. If we render our imagines worlds with enough faith in the aliveness of things, we give our readers a chance to feel that aliveness with us. This aliveness—which we feel when entranced in a hypnagogic state or enthralled by great literature—is where we dwell, and to reach it both readers and writers must reach through the veil of the soul to commune by touching what we cannot see.

This fifth lesson from Poe, the hardest to learn, has brought me to a new appreciation of the hero I so naively fell in love with. I swallowed the lure of hypnagogia even though I didn’t understand what it really meant, and it dragged me somewhere deeper than I suspected. It was a youthful mistake that just might last me my whole lifetime.

Image from Wikimedia Commons (by Vallotton)

Quotes and Notes is a monthly craft essay series by Steven Wingate. Steven teaches at the University of Colorado. His short story collection Wifeshopping won the 2007 Bakeless Prize in fiction from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and was published by Houghton Mifflin in 2008.

Quotes and Notes is a monthly craft essay series by Steven Wingate. Steven teaches at the University of Colorado. His short story collection Wifeshopping won the 2007 Bakeless Prize in fiction from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and was published by Houghton Mifflin in 2008.