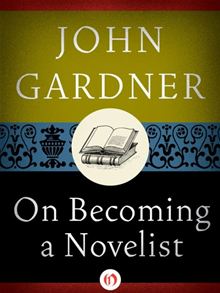

“For the writing teacher, the habit of intellectual analysis may become crippling…. As the teacher sees more and more talented students, he may consciously or unconsciously begin to set himself increasingly difficult tasks, distancing himself from his best students’ work by tour-de-force showmanship, pyrotechnics, and subtlety beyond his students’ means.”

— John Gardner, On Becoming a Novelist

All creative writing students are not created equal; teachers and students know that equally well, and everyone involved can see who has the most talent and drive. If teachers get lucky, we have one flat-out brilliant student every few years whose presence raises an entire workshop, emboldening all those in it to reach beyond their self-imposed limitations. I’ve been lucky to have had a handful of students whose talent, fearlessness, and fluidity struck me so forcefully that I wished I could rewind my own life twenty years back so I could try to be more like them.

Such students can, and ought to, change those who teach them. It needn’t be a negative change as John Gardner describes above, in which the brilliant student becomes a nemesis. But such negativity does happen, because our best students tempt us into self-doubt. In the worst case scenario teachers can get paralyzed, both in the classroom and at the writing desk, by the worry that their students’ aesthetic instincts are simply better than their own. This fear may lead teachers into over-intellectualizing the creative process in an effort to give the brilliant student more challenges, which I believe is absolutely inimical to good instruction. And as Gardner warns, this jealous rot can eventually find its way into the writer/teacher’s own creative work.

Such students can, and ought to, change those who teach them. It needn’t be a negative change as John Gardner describes above, in which the brilliant student becomes a nemesis. But such negativity does happen, because our best students tempt us into self-doubt. In the worst case scenario teachers can get paralyzed, both in the classroom and at the writing desk, by the worry that their students’ aesthetic instincts are simply better than their own. This fear may lead teachers into over-intellectualizing the creative process in an effort to give the brilliant student more challenges, which I believe is absolutely inimical to good instruction. And as Gardner warns, this jealous rot can eventually find its way into the writer/teacher’s own creative work.

Writers with a solid practice and sufficient maturity don’t need to worry about trying to outdo our best students. But such students can knock even the most grounded teachers off balance by challenging us, whether consciously or not, to be more articulate and more precise in our instruction. This requires risk and effort. It’s as dangerous to deny that brilliant students require special handling as it is to believe that all students are created equal. Pretending that talent doesn’t exist dishonors everyone in the workshop equally. Here are a few thoughts and observations on dealing with phenomenal students:

Don’t resort to merely teaching technique. The worst thing we can do with brilliant students is to offer them greater technical challenges—exploring a particular form for the sake of exercise, altering point of view for no good reason, etc. Writing isn’t Olympic diving, and there are no “degree of difficulty” points to be earned. Focusing on technique is a cop-out for the teacher; it tacitly embraces the creation of pretty surfaces at the expense of emotional truthfulness, and it gives students permission to indulge in cleverness and call it art.

There is no value whatsoever to false egalitarianism. Everyone in workshop will recognize the best work presented, and teachers need to avoid two poles: (1) not critiquing the piece at all; (2) taking the author to task on every single possible nit that can be picked. Tearing apart Student Z’s brilliant story for half an hour simply because one did the same to Student X’s glaringly unfinished work can smother a whole workshop. Fairness does not mean equal time for pointing out perceived errors.

Insightful praise for good work can be instructive for everyone. I would hate to count the number of teaching moments that get missed in creative writing classrooms because teachers, too invested in egalitarianism and unwilling to play favorites, won’t come out and recognize stellar student work. If it’s blazingly good, we should say so and talk about why. If part of what we do in workshops is train people to read like writers, is there any reason why the texts that help us read more intuitively can’t come from our own students?

Modeling the habits of the writer is more important than modeling structure or style. Gifted student writers will find their way to well-structured tales and compelling voices. But even the most talented may have little sense of how to manage and nurture their projects, how to balance their analytical and creative selves in revision, or how to write their way through (rather than around) the irresolvable knots that rise up in every earnest work of fiction. No matter how impressive pieces are in workshop, their authors must eventually bring them to fruition alone. It’s our responsibility to teach them about the ever-shifting sands that fiction (and its authors) face over the long haul of a project or a career.

Guide brilliant students toward the creative questions that won’t go away. We may not have our best students for long, but we can do them a great service by pushing them toward the thorny questions that will assert themselves with each new project, or even between phases of a single project. Am I revising for the sake of revising? What road does this work lead me down, and what other roads might it also lead me down? Process awareness is a tremendous talent in itself, and there’s no reason to withhold conversations about it from students who are otherwise ready.

Cultivate articulateness about the craft and broad literary citizenship. Brilliant students are more likely to be published and more likely to be teachers in the future; they will therefore need to be more articulate about the craft of fiction so that they can teach it, speak in interviews about it, and craft spectacular grant proposals involving it. We should challenge them not only to be workshop leaders, but also to think about the big picture of their writerly apprenticeship. We should encourage them to figure out where they fit in the republic of arts and letters, since they will probably—through publication, advanced degrees, etc.—need to address such questions more quickly than their fellows.

One last note on Gardner’s warning about brilliant students adversely affecting their teachers’ writing. People who are jealous and overly competitive by nature, and who view writing as a means of getting ahead rather than a process of understanding the self and the world, are likely to fall into that trap. But I don’t think most creative writing teachers are like that. Most of us, if our students turn out to be great writers, will feel overjoyed and privileged to have been among their teachers. If we don’t feel that way—well, then it’s probably time to get out of the business.

Quotes and Notes is a craft essay series by

Quotes and Notes is a craft essay series by