Editor’s Note: Leah De Forest’s essay on subject position in fiction begins with an examination of Allan Gurgansus’s “Blessed Assurance.” She writes:

How best to characterize Jerry’s subject position? We can talk about race, gender, class, and education—and all of those elements are relevant. Jerry enjoys structural privilege as a white person and a man. As the poor son of mill workers, he is less economically privileged than the other white people in his community. But he is gaining an education, which is a key part of his social mobility. But this doesn’t give me everything I need to understand what animates the story. It can’t account for the complexities in the interactions between characters, the interpersonal negotiations that can shift power dynamics.

You can read Part I of this essay here. Part II of the essay continues below.

“Brownies”: A student of power and the ubiquitous half-seen

One of the challenges of writing about privilege is the day-to-day nature of it. As Charles Baxter writes in his essay on defamiliarization, “familiarity, after all, is a kind of power, the power to predict and the power to abstract . . . it signals that our defenses are in place and are working. The kingdom is running smoothly.” If we all stay within the terms of our shared agreement, nobody has to talk about it, and life continues along its comfortable ruts.

The child narrator of “Brownies,” Laurel, lives within a number of agreements that are to her detriment. She’s a girl, for a start, and she’s Black. She is aware of those facts about her relative level of privilege, and to some extent understands what they mean in the wider world. She sees white people “coo-coo over dresses” and “swish by importantly” and understands that adulthood is “full of sorrow and pain, taxes and bills, dreaded work and dealings with whites, sickness and death.” But one gets the sense that to date, she has largely thought in terms of the kingdom running smoothly.

The events of “Brownies” appear designed to disrupt that. As the story opens, Laurel and her fellow fourth-grade troop members agree to “kick the asses” of the white girls in Troop 909. Laurel, known as Snot thanks to a sneezing incident back in first grade, is an unwilling participant in the planned assault at Camp Crescendo. Back at school, troop social leaders Arnetta and Octavia had coined the use of “Caucasian” as a playground taunt. At camp, the pair spearhead the “ass kicking” plan based on the lie that one of the white girls used a racial slur against one of their group members, Daphne. But when the confrontation occurs, Laurel’s troop realizes that Troop 909’s members are intellectually disabled. The ass kicking is off, and Arnetta goes into damage control, trying to manipulate the Troop 909 girls into not telling the group leaders. But the adult leaders of both troops find out. Troop 909’s leader is conciliatory. Laurel’s troop leader, Mrs. Margolin, is angry. She keeps a close watch on the girls until they head home the next day. On the bus, Arnetta mocks the 909 troop girls’ posture and facial expressions. Laurel tells a story about her father asking a group of white Mennonites—whose religion dictates that if someone asks them to do something, they must do it—to paint his porch because, as he told her, “it was the only time he’d have a white man on his knees doing something for a black man for free.”

I’ve puzzled over how best to characterize Laurel’s subject position. Her structural privilege is clear. Her attitude, how she regards herself and her place in the world, is trickier to describe. I think that’s because Laurel, like the events of the story, exists in two worlds: the social dynamics of Laurel’s Brownie troop (which extends by implication to the Black community she lives in) and the wider society. Within the wider world, Laurel enjoys little structural advantage. Within the Brownie troop, she’s also pretty low on the pecking order. But although Laurel doesn’t appear to enjoy her place in this pecking order (she is loath to speak up because she knows she’ll be called Snot, for example), her attitude is often one of curiosity or disdain. Laurel is neither at the top nor the absolute bottom of the social structure within the troop, which makes her an ideal observer. She may not be quite willing to participate in the planned ass kicking, for example, but feels like she’s “defending something” nonetheless. She watches the ways that Arnetta and Octavia exert influence, but she doesn’t try to befriend them. She’s more interested in making friends with Daphne, whom she admires for her intellect.

I’ve puzzled over how best to characterize Laurel’s subject position. Her structural privilege is clear. Her attitude, how she regards herself and her place in the world, is trickier to describe. I think that’s because Laurel, like the events of the story, exists in two worlds: the social dynamics of Laurel’s Brownie troop (which extends by implication to the Black community she lives in) and the wider society. Within the wider world, Laurel enjoys little structural advantage. Within the Brownie troop, she’s also pretty low on the pecking order. But although Laurel doesn’t appear to enjoy her place in this pecking order (she is loath to speak up because she knows she’ll be called Snot, for example), her attitude is often one of curiosity or disdain. Laurel is neither at the top nor the absolute bottom of the social structure within the troop, which makes her an ideal observer. She may not be quite willing to participate in the planned ass kicking, for example, but feels like she’s “defending something” nonetheless. She watches the ways that Arnetta and Octavia exert influence, but she doesn’t try to befriend them. She’s more interested in making friends with Daphne, whom she admires for her intellect.

Where does that leave us in terms of movement? Unlike Jerry in “Blessed Assurance,” Laurel doesn’t make any (upwards) structural movement. Nor does she particularly improve her status in the Brownie group, although she does capture the group’s full attention when she tells the Mennonite story. The answer, I think, is in the reversals that mark the story. We see this from the opening lines, which present us with the most benign-seeming ensemble group—a Brownie troop—and then adds an ass kicking. The Brownie troop’s plan effects a power reversal, making the white girls the potential victims of racially motivated violence. In this world, Caucasian is a slur and Laurel’s group are the powerful “predators.” But this only persists for the first half of the story; we swing back to the status quo when Laurel’s group learns that Troop 909’s members are intellectually disabled. These reversals tip the world of the story and the power dynamics within it. Laurel watches. She’s a student of power, and the primary, defining movement of this story—its reversals—facilitate her study.

With Octavia and Arnetta positioned as aggressors, Laurel is given a live demonstration of the functioning of power. She sees, for example, how Octavia’s long hair causes the other girls to listen to her “reverentially” and the way Arnetta uses her command of Mrs. Margolin’s religious acrostics to manipulate the troop leader into believing whatever she says. To justify their attack plan, Octavia and Arnetta need nothing more than a made-up accusation and a commitment to “teach them a lesson.” A reader of history will recognize a pattern, even if Laurel does not.

From Laurel’s position—still sheltered enough from the wider world to think of white people as being as rare as baby pigeons, but curious about the workings of power—the realities of racial violence remain a distant, unspoken threat. As in “Blessed Assurance,” in “Brownies,” narrative distance allows a reader to understand more than the character can. We see this particularly after the attempted attack in the bathroom, when Octavia and Arnetta’s power has been deflated and white privilege is brought to the fore. In the moments after the leaders appear in the bathroom, Mrs. Margolin threatens her troop with punishment. The Troop 909 leader, however, takes the soothing upper hand:

“It’s all right, it’s all right,” the 909 troop leader reassured Mrs. Margolin. Her voice lilted in the same way it had when addressing the girls. She smiled the whole time she talked. She was like one of those TV-cooking-show women who talk and dice onions and smile all at the same time. “See. It could have happened. I’m not calling your girls fibbers or anything.”

The Troop 909 leader knows she is in charge. She doesn’t need to be angry; she treats Laurel’s troop as vulnerable. She patronizes Mrs. Margolin with her syrupy voice. In a classic PR move, she denies “calling your girls fibbers,” which of course introduces the notion that they are lying. The leader goes on to demonstrate the Troop 909 members’ disabilities, patronizing pretty much everyone in the room and commenting that not all of the Troop 909 girls’ parents are the most “progressive.” As if racism were simply a matter of being old-fashioned. One almost cheers for Arnetta when she steps forward in the next paragraph, trying to pin the speaking of the racial slur on one of the Troop 909 girls at random—it’s unjust, but it’s a pushback. Laurel’s troop and its leaders, however, can only back away from this interaction. In its wake, “Mrs. Margolin and Mrs. Hedy guarded us so closely, almost no one talked for the entire day.” Laurel does not say why, but she appears to understand that she and the troop need guarding—and it’s not just to stop them from being naughty. Here, the child’s position as learner becomes the medium through which a reader catches a glimpse of the taken for granted, the near-invisible, and the unspoken fear that can lie beneath it.

Characterization of others: Troop 909

“When you’ve been made to feel bad for so long,” Laurel thinks near the end of the story, “you jump at the chance to do it to others.” This is how Laurel understands her father’s decision to ask the Mennonites to paint his porch; it’s also, one assumes, how she thinks about her troop’s plan to attack Troop 909. The reasoning is clear enough: the oppressed hit back at the oppressor. Follow that thought a little further, and you get the notion that without the oppressor, the oppressed would be quite nice people.

I’m fairly sure that’s not what this story is driving at.

When I first turned my mind to the question of how Laurel’s subject position affects the characterization of the others in this story, I hit a wall. Who, exactly, were the others here? I had always thought of “the other” in one-way hierarchical terms. In line with Morrison’s formulation in which American Africanism creates the identity of the white, male default, the philosopher Zygmunt Bauman describes how this process works across a range of social identities:

Abnormality is the other of the norm, deviation the other of law-abiding, illness the other of health, barbarity the other of civilization, animal the other of human, woman the other of man, stranger the other of the native, enemy the other of friend, “them” the other of “us,” insanity the other of reason, foreigner the other of the state subject, lay public the other the expert.

Here, power rests clearly on one side of the binary—the side of lesser privilege. But viewed in this way, Laurel herself is other. What does it mean to experience the story from the position of other? This story teaches us that it depends on the context. According to the terms of the first half of the story, the girls in Troop 909 are other. As we’ve seen, Laurel’s fellow troopers are young enough to be aware of white privilege and external norms, but separate enough from the adult world to believe in their power to beat up the white girls. While the plan is being made, the Troop 909 girls are other.

What struck me about the characterization of the Troop 909 girls is how slight it is. We see them walk by from a distance, with their shiny hair and brightly colored sleeping bags, in the opening scene; we don’t see them again until six pages later, deferring to Laurel’s group in the restroom, somehow only seen from afar, “never within their orbit enough to see whether their faces were the way all white girls appeared on TV—ponytailed and full of energy, bubbling over with love and money.” Laurel just sees types. The next line is telling, both for what it signals about the white girls and what it shows about the way Laurel views them: “Some of them rapidly fanned their faces with their hands, though the heat of the day had long passed. A few seemed to be lolling their heads in slow circles, half purposefully, as if exercising the muscles of their necks, like Stevie Wonder.” An even mildly attentive reader will pick up that there is something different about the 909 girls. Their hand and head movements signal the strong possibility of some kind of neuro diversity or intellectual disability. But none of Laurel’s troop members seem to notice. Arnetta’s next statement is “we can’t let them get away with that,” meaning, on some level, existing. The story then moves to the development of the ass kicking plan, and it’s another three pages before we encounter Troop 909 again, this time “dancing around the mound of hockey balls, their limbs jangling awkwardly, their cries like the constant summer squeal of an amusement park.” Narrative distance allows a reader to see that the 909 girls are disabled, and begin to anticipate what will happen when the confrontation occurs. But from Laurel’s position in the story, the white girls remain types—privileged stick figures who exist largely in contrast to her troop, strengthening Arnetta and Octavia’s identities as tough girls.

Turning now to the confrontation scene. The first specific appearance we have of any of the Troop 909 girls is the voice of an unnamed “big girl” who denies that the slur was used. Laurel notices the girl’s voice sounds “as though her tongue were caught in her mouth”; when she goes into the bathroom, the first thing we see is five girls huddled up to this one larger girl. There is no physical description of the girl, other than her size and the workings of her mouth, which hangs open, and her tongue, which “grazed the roof of her mouth, like a little pink fish.” Octavia says they are going to leave, and that Troop 909 doesn’t have to tell anyone they were there. But the big girl is not having it. “Why not?” she taunts. “You’ll get in trouble. I know. I know.”

In this page and a half of scene, the girls in Troop 909 have moved from white-girl cut-outs to specific individuals. We can see counterpoint in the way they’ve resisted Laurel’s expectations—they’re not TV girls bubbling over with “love and money,” and nor are they the helpless victims their disabilities might cause Laurel to assume them to be. There’s a kind of leveling of the power here, in which Laurel and her troop’s Blackness, and Troop 909’s disabilities, mark both groups as other. Laurel’s learning curve is in going from viewing the white girls as types to specific people. But, as we saw above, the appearance of the Troop 909 leader disturbs this leveling. The woman comes in and the girls crowd her, reminding Laurel of “a hog I’d seen on a field trip, where all the little hogs gathered around the mother at feeding time, latching onto her teats.” The Troop 909 girls are infantilized by this figure (by comparison, Mrs. Margolin is a self-important duck), who has not heard any of the big girl’s defense of her group, does not ask about it, and goes ahead assuming that the slur might have been used. On the bus home, the girls mock Troop 909, but they also mark their shared status as other:

“You know,” Octavia whispered, “why did we have to be stuck at a camp with retarded girls? You know?”

“You know why,” Arnetta answered. She narrowed her eyes like a cat. “My Mama and I were in the mall in Buckhead, and this white lady just kept looking at us. I mean, like we were foreign or something. Like we were from China.”

“What did the woman say?” Elise asked.

“Nothing,” Arnetta said. “She didn’t say anything.”

A few girls quietly nodded their heads.

Here is a child’s acknowledgement of the goes-without-saying: the ubiquitous half-seen functioning of privilege that maintains the status quo by marking groups as other. As Arnetta appears to recognize, a person from China, a Black child, or a disabled person might all fall into that category. But none of the characters in this story is represented only as oppressors or only oppressed. The reversals at the heart of the story allow a view around the monolith of privilege that would otherwise obscure individuals and the complex relationships between them. Those binaries, Black and white, man and woman, self and other, exist in the world of this story; privilege is integral to its function. But as Laurel’s story shows, these systems of meaning don’t operate in a neat system hovering above our social reality. They’re embodied. Messy, powerful, scared, confused. None of us quite gets it.

Laurel, student of power and privilege, realizes “there [is] something mean in the world that I could not stop.” Yes, there is: people. And fortunately, occasionally, they are kind.

Disgrace: A tantruming man and his impossible truth

In recent years, it’s been difficult to avoid a particular kind of figure in the news. This person will be angry and nostalgic; quite likely he (it is often a he) will be red in the face. He is eager to protect all that is good and right, and he does not appreciate being asked what he means by that (nor why he feels he has to defend anything in the first place). He smirks and protests and, given the opportunity, he might even loom.

One might think of such people as human tantrums.

Disgrace is in many ways one long tantrum. David Lurie, fifty-two, is in the process of a privilege adjustment. He is a middle-aged white man living in post-apartheid South Africa who has enjoyed the privilege of gender, race, and education. He is an adjunct professor of Communications at Cape Technical University, having lost his professor status to program rationalization. He has published three scholarly books on subjects such as opera and Wordsworth and is starting a new one on Byron, an opera: “a meditation on love between the sexes.” David is also a womanizer who, as he explains in the novel’s opening pages, has been enjoying the “moderated bliss” of weekly appointments with a sex worker, Soraya.

He has, to his mind, solved the problem of sex rather well. On Thursday afternoons he drives to Green Point. Punctually at two p.m. he presses the buzzer . . . waiting for him at the door of No. 113 is Soraya. He goes straight through to the bedroom, which is pleasant smelling and softly lit, and undresses. Soraya emerges from the bathroom, drops her robe, slides into bed beside him. “Have you missed me?” she asks. “I miss you all the time,” he replies. He strokes her honey-brown body, unmarked by the sun; he stretches her out, kisses her breasts; they make love.

David appreciates Soraya’s docility. Note the language: he “stretches her out.” He is aware that this is a business transaction, but he hopes that perhaps she might see him on her own time. All is well enough for David until he encounters Soraya in the street. Soon after, Soraya stops taking David’s appointments. Here begins the tantrum. David has lost his “power” with women. The good looks and charm that were once the “backbone of his life” have gone. He meets with another sex worker, whom he finds “coarse”; he has sex with a married colleague, whom he finds repellently effusive. So he initiates an affair with one of his students, Melanie Isaacs. They start sleeping together and on one occasion, David rapes Melanie (a crime he never acknowledges): “Not rape, not quite that, but undesired nevertheless, undesired to the core. As though she had decided to go slack, die within herself for the duration, like a rabbit when the jaws of the fox close on its neck. So that everything done to her might be done, as it were, far away.” What is rape if not sex without consent?

This affair and the sexual assault lead to the professional disgrace of the novel’s title. David, faced with a professional-review committee whose chair is eager to find a way to get past “this harassment business,” behaves like a petulant child. He refuses counseling. He will not apologize. He does not wish to see Melanie’s statement of complaint; he knows “of no reason why Ms. Isaacs should lie”; he’s guilty of all that he’s been charged with. His language and demeanor imply that the committee is a politically motivated trial. When pressed, David explains that he was not himself. “I was no longer a fifty-year-old divorcé at a loose end. I became a servant of Eros.”

This is eye-rolling stuff. David is being pompous, evasive, and blind. As a committee member says: “Yes, he says he is guilty; but when we try to get specificity, all of a sudden it is not abuse of a young woman he is confessing to, just an impulse he could not resist, with no mention of the pain he has caused.” In the next paragraph, David remembers how Melanie barely stands at his shoulder. “Unequal,” he thinks. “How can he deny that?” And yet he rankles at contrition. Later, when David is visiting his daughter, Lucy, at her property on the Eastern Cape—shortly before he and Lucy are attacked by three men, and Lucy is raped—David remembers Melanie’s arms flopping “like the arms of a dead person” but still clings to the “servant of Eros” notion. He tells Lucy about a neighbor’s dog, which was beaten for being excited by a nearby bitch in heat. “What was ignoble . . . was that the poor dog had begun to hate its own nature.” David believes—though he would deny it in polite society—that on some level he had a right to treat Melanie the way that he did. And he is confused and displeased that the wider culture no longer appears to agree.

Recalling the formulation that we’ve been applying—identify levels of relative privilege (high), consider character attitude (petulant), and locate a sense of movement—the direction here is clear: down. As the novel progresses, David loses more: his job, his belief that he understands his daughter (it’s unlikely he ever has), his sense of intellectual worth, and his sense of safety. His response is entitled displeasure: when Soraya refuses to see him any longer, he shows up at her home. When he is censured at his workplace, he subverts the process. He is a man who has been accustomed to a very full invisible knapsack. Coetzee takes all that away. When Lucy suggests he ask her Black co-proprietor, Petrus, for work, David says, “I like the historical piquancy,” clearly not liking it at all.

Recalling the formulation that we’ve been applying—identify levels of relative privilege (high), consider character attitude (petulant), and locate a sense of movement—the direction here is clear: down. As the novel progresses, David loses more: his job, his belief that he understands his daughter (it’s unlikely he ever has), his sense of intellectual worth, and his sense of safety. His response is entitled displeasure: when Soraya refuses to see him any longer, he shows up at her home. When he is censured at his workplace, he subverts the process. He is a man who has been accustomed to a very full invisible knapsack. Coetzee takes all that away. When Lucy suggests he ask her Black co-proprietor, Petrus, for work, David says, “I like the historical piquancy,” clearly not liking it at all.

This loss of privilege requires David to face the reality that the power he once enjoyed was a result of privilege. If he accepts that, it follows that perhaps he is not as clever as he thought he was; that people don’t like him as well as he believed; that the good life he had up till now enjoyed was a result of good luck rather than inherent worth. To a tantruming man, this is a reality to be avoided at all costs. It’s impossible. David’s positioning as a tantruming man, then, invites readers to experience privilege as an impossible truth.

As noted, Disgrace uses omniscience. The psychic distance (the space between the narrator and David’s thoughts) remains consistently close, but we’re not always entirely inside David’s thoughts, and we don’t experience the world of the novel solely through David’s position. We see this in the authorial flagging in the first line: “he has, to his mind, solved the problem of sex rather well” (emphasis mine). I’ve found it helpful to think of this close third-person limited omniscience as primarily curatorial in nature. We don’t experience the narrator’s voice as strikingly different from David’s; the narrator has access to the same logistical information as David (for example, David never reads Melanie’s formal complaint, and we never learn the text). We feel the narrator as an arranging force. There are many places in the novel where David says or does one thing, and the world of the story contradicts him. For example, David takes Melanie out to dinner and tells her he “won’t let it go too far”: six lines later, he has sex with her on the living room floor. We also see this curatorial influence (and ensuing narrative distance) in the moments before David and Lucy are attacked: David uses the dog analogy to explain his actions with Melanie moments before three men rape his daughter.

Are these men also “following their instincts”? David doesn’t appear so sanguine. “Take everything. Just leave my daughter alone,” he pleads during the attack (though of course he did not leave Mr. Issacs’s daughter alone). None of the characters draws a direct line between the two rapes, but a reader is invited to wonder: how is it that David doesn’t see the connection? Is it because he believes, on some level, that he ought to be allowed to have sex without consent? It’s fraught to draw an equivalence between any two crimes (which will each have a distinct and lasting impact on their victims), but it’s worth noting that David never entertains the notion that his daughter’s attackers were “servants of Eros.” There is an undeniable (and nasty) privilege at work here, one that David finds impossible to know.

Characterization of others: Lucy

How, then, does David’s subject position affect the characterization of the others in Disgrace? Lucy and Petrus both appear as foils to David’s misunderstandings and character flaws. For the sake of space, I’ve focused on Lucy. From the moment she appears, David’s expectations of his daughter—as a “nice girl,” ample, a countrywoman—are subverted. He, of course, doesn’t see it. Lucy hugs David hello, but her conversation is closed off. She talks about the weather, doesn’t explain why her lover, Helen, has left, mentions that she owns a rifle, and offers to show him around. We understand Lucy tolerates her father but doesn’t buy his perspective. Moments after thinking that if Lucy is what he leaves behind, he needn’t be ashamed, David mentions that he wants to write his opera in order to “leave something behind.” And as the story proceeds, Lucy continues to challenge him. She also introduces him to her friend Bev Shaw, whom David initially finds irredeemably unattractive but ultimately—as Lucy predicted—interesting.

But something about Lucy’s characterization bothers me. I can’t help feeling that Lucy becomes a victim of narrative design—that she’s raped because her father raped Melanie, and her presence in the story serves at least in part to defy David’s belief that he is the center of things. There is a metafictional moment which calls attention to this shortly after Lucy tells David that she is pregnant:

David, I can’t run my life according to whether or not you like what I do. Not any more. You behave as if everything I do is part of the story of your life. You are the main character, I am a minor character who doesn’t make an appearance until halfway through. Well, contrary to what you think, people are not divided into major and minor. I am not minor. I have a life of my own, just as important to me as yours is to you, and in my life I am the one who makes the decisions.

Does she, though, make the decisions? It seems that she mostly reacts, accommodates, accepts. When Petrus says he is willing to marry her, Lucy understands the offer of an alliance—and asks David to tell Petrus she accepts his terms. She’ll give Petrus her land in exchange for protection but insists that she keeps her house. “Otherwise,” she says, “I am without protection, I am fair game.” How humiliating, David says.

“Yes, I agree, it is humiliating. But perhaps that is a good point to start from again. Perhaps that is what I must learn to accept. To start at ground level. With nothing. Not with nothing but. With nothing. No cards, no weapons, no property, no rights, no dignity.”

“Like a dog.”

“Yes, like a dog.”

Perhaps what I’m struggling with is not so much David’s subject positioning as the omniscient narrator’s positioning. In “Blessed Assurance” and “Brownies,” the narrator is a future version of the protagonist. This narrator appears similar to David—as noted, the narrator only knows as much about the story’s events as David does. But the narrator exerts a bitterness which spares no one, least of all David. We’ve seen that in the way the novel deploys irony, teaching a reader not to trust David’s take on events. We also see it in the way the novel’s events are arranged: Lucy’s rape echoing David’s assault on Melanie, for example. This amounts to a kind of double positioning—David’s tantrum and the omniscient narrator’s bitter acceptance.

Yet the novel is not without hope. True, it’s scathing about David and pessimistic about the future in post-apartheid South Africa; clearly, the land reparations overseen by the government (which funded the grant that allowed Petrus to buy a share of Lucy’s land) will not lead to peace in the short term. But Petrus is building his home, establishing a farm, taking care of his family. This reminds me of the reversals we saw in “Brownies”; the sense that the world of the novel has been tipped on its side, upsetting the established order of privilege. Only in this case, for David and for Lucy, the reversal goes in the other direction, and the change is permanent.

Which brings us to dogs. Lucy keeps dogs on her property (the attackers shoot all of them except one). David recalls the dog taught to “hate its own nature.” Bev Shaw puts unwanted dogs to sleep, with David’s help. Towards the end of the novel, David is going to the incinerator to personally place the dogs’ bodies inside. He does this out of respect, because if he doesn’t, workmen will break the rigor mortis–affected carcasses up and jam them into the fire. I don’t presume to draw a linear meaning out of all of this—if that’s what I wanted, I wouldn’t be reading novels—but it asks me to look at Lucy differently. Maybe in refusing the report the rape and deciding to stay on, Lucy makes an adjustment David cannot. In accepting a future in which she has “no property, no rights, no dignity,” Lucy is accepting a reversal of privilege. In that sense she is, as Bev Shaw says, “closer to the ground than . . . either of us.” It isn’t fair to her, any more than life is fair to anyone, least of all the dogs that are called into service according to human requirements: as attack animals, as companions, as excess waste.

As the novel closes, David Lurie—disgraced, disfigured professor, having abandoned his Byron opera—leads his favorite dog to its death at Bev Shaw’s hand. His tantrum is done; his grandchild’s life soon to begin. And this omniscience, the novel’s bitter guiding hand, is aligned most closely not with humans but somehow, as it has been all along, with the dogs.

Tipping the star-disc

Like a lot of kids, I spent a chunk of my playground hours observing dynasties. The dominant kids were fascinating. The way they could single out a physical trait and build a campaign of humiliation around it, how they banded together to create a wall of coolness around themselves. Most of the time I observed from the dumb end of the monkey bars or whatever playground zone was reserved for the midi-losers. Laurent, therefore, presented an opportunity. I felt a rush of pleasure when Laurent hurt himself because the stumble confirmed what I had come to believe: that I was better than him. Therefore, his injury was amusing.

Nasty, huh? I saw myself as a victim. I was a bully.

Writing these words, my backside is already halfway out of the chair. What I experienced as a raising of my pecking-order position as a child lowers me as an adult. I won’t get into the next question—am I a good person, or not?—because as I hope we’ve established, that’s not the point. We all exist in complex networks of privilege and power, negotiated between as many points on the map as there are people on the planet. Taking that as a given, what’s interesting is movement.

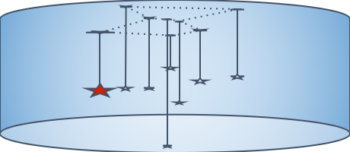

As a child, I perceived my direction as up. In hindsight, I find the reverse: character-me’s positioning in the story hasn’t changed, the geometry has. It’s not only that I’m looking at it from a different perspective: it’s that the whole disc has shifted. The stars remain the same distance apart, but on this angle—let’s say tipped forty degrees—my position is lower than Laurent’s. We might think of David Lurie’s disc making a similar downward movement; of Laurel’s being temporarily overturned, and of Jerry/Gerald’s on an upward incline (forcing him to justify his position).

Figure 5: The side-on view . . . (Images credit: Luke Fletcher)

Figure 6: Rotated.

But wait, I hear you say: you’re asking me to think about these stories as determined by a particular position inside the disc and yet somehow at a remove. Narrative distance and omniscience—isn’t that a bit like the zoomed-out view? Well, I’ve come to believe that a once-and-for-all understanding is not only impossible but actually, when writing across different levels of privilege, the problem. Or my problem, at least. I’d been assuming that there’s a “right” way to look at the world. That if I achieved some God-like understanding, I’d be able to set aside my anxiety and get on with capturing the “truth.” But as Robert Boswell reminds us, omniscience isn’t all-knowing: “Fiction writers are not deities. We don’t mind being treated as such, but the truth is we’re merely poseurs.”

Omniscience, as we saw in Disgrace, has its own position. As does all communication, emanating as it does from inside a flesh-and-bones head. Narrative distance is a tool used by a human writer to gesture towards something a character does not see—and this, too, comes from a particular position. The zoomed-out view is a projection, a myth—to paraphrase Simone de Beauvoir, it’s point of view that’s been “confuse[d] with the absolute truth.”

Where does this leave us as writers? If a God-view is impossible, we must accept that we’ll never fully get a grip on the world we’re trying to render. But that needn’t be a handicap. Quite the contrary. To paraphrase Dean Bakopolous, doubt is at the center of everything writers do. Inching forward with projects, we might perform the magic trick of projecting ourselves into various positions in our stories. We can try experiencing it from here, and here, and here. Each of these three texts shows how positioning a narrator within the world of the story can be effective in bringing characters to life; how it can invite us to experience the complexities of privilege and power in both complex and specific ways; how the choices we make about where the storyteller stands inside the hierarchies and personal dynamics of a story can open up, rather than limit, ways of writing about privilege and power.

Clearly, writers need to be aware of how privilege functions in the world and in our work. We won’t always get it right. But if we don’t try, if we don’t look privilege squarely in the eye, then privilege is all we will see: the unspoken status quo will pass before us and we’ll be at risk of reproducing it. We’ll be stuck on the monkey bars, in the land of polite playground conversation. And whatever you think about the state of the world today—however you interpret the meaning-agreements that influence who gets what and who laughs at whom—I think we can agree that polite conversation is rarely fodder for engaging fiction.

One more thing. I concede that I am, in fact, suggesting we think about stories from specific positions inside the disc and at a remove. But it’s not an all-knowing remove; it’s a specifically knowing remove. Arrangement matters. I’m talking about the way we assemble character ensembles, determine back story, stage-manage conflict, deploy irony, and so on. I’m also thinking about our ability to shift things: to tip the disc. What happens, one wonders, if I do this? Who has the power now, and how will they use it? What does that allow me to bring out on the page? Writers don’t have to be all-knowing to manipulate the disc. But attentiveness helps. Hopefulness, too.

Oh, and if you’re out there somewhere, Laurent: I’m sorry I was a jerk.