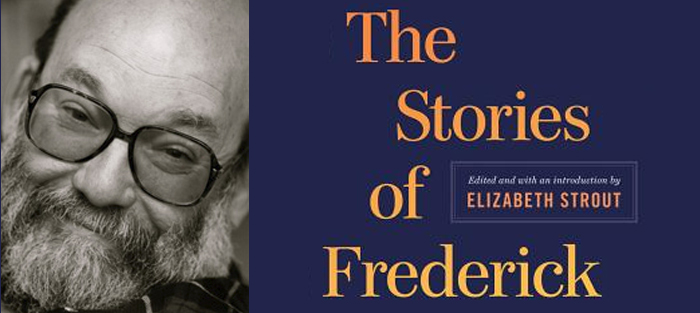

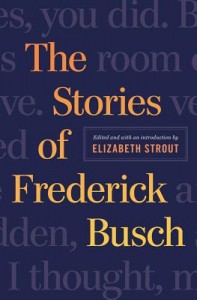

The newly published The Stories of Frederick Busch (W.W. Norton and Company) arrived in the mail two weeks ago. A bittersweet gift. I could almost fool myself into believing that Fred, my friend and mentor, was still sequestered in his workroom at his farmhouse in upstate New York, surrounded by his ziggurats of books, jotting notes on his tablets, and typing away at his latest (by my count, 27th) book. But he isn’t.

The newly published The Stories of Frederick Busch (W.W. Norton and Company) arrived in the mail two weeks ago. A bittersweet gift. I could almost fool myself into believing that Fred, my friend and mentor, was still sequestered in his workroom at his farmhouse in upstate New York, surrounded by his ziggurats of books, jotting notes on his tablets, and typing away at his latest (by my count, 27th) book. But he isn’t.

Seven years ago I wrote in my journal this simple pronouncement: Fred is dead.

Frederick Busch was my first writing teacher—my undergraduate writing teacher. Is there any way to sound the importance of this? I was an insecure girl from the tony Long Island suburbs set adrift in a sea of finance majors bound for Wall Street. All I wanted was to get into his Spring semester, freshman year writing workshop, so I wrote, for the sake of writing!, a story about a young boy watching the meltdown of his Vietnam vet uncle. I remember walking into Professor Busch’s office, hands and legs trembling, handing him the story, and turning to leave.

“No, no,” he said, his hand on his bearded chin. “Sit. I’ll read it now.”

Now. While I watched.

His face gave away nothing. He looked up. “Well, it’s awfully sentimental, Kerry, but you’ve risked something here. You’ve got a space.”

His first impromptu lessons: be willing to risk everything—sentiment and heart—for a story; even failure might lead to gain.

In that first workshop, Fred had us read Hemingway’s “Indian Camp.” I remember the brutality of that story as Nick watches his father perform the impromptu Caesarian on the Indian’s wife with a jackknife and the Indian is then discovered dead, having cut his own throat, unable to take the screaming of his wife. Yes, the brevity and muscularity of language was important, but for Fred, it was how Hemingway’s characters acted under pressure. Fred kept pushing us away from our passive stories. “The doctor’s ability not to hear the woman’s screams is necessary for his psychic survival,” Fred said. “So is writing if you are going to be a writer. Writing, like breathing, is a matter of living and dying.”

Another lesson, delivered in the canonical intonation of High Mass, was “Love and Serve Your Characters.” Fred would sit at the head of the workshop table, shaking his head in disappointment and wonder as to why we mistreated our characters in such ironic, dispassionate ways; why we manipulated them without concern for their welfare; why we didn’t weep for their sufferings which we had caused with our pens. Of course, Fred’s empathy ran deep for his own characters, people going through hard times—husbands and wives, fathers and mothers, families bruised and battered, trying to heal.

The very first line of the very first story, “Widow Water,” in the new The Stories of Frederick Busch, reads, “What to know about pain is how little we do to deserve it, how simple it is to give, how hard to lose.”

At the end of that first semester, Fred called me into his office. Since he was direct in his assessments, I was convinced that he was going to tell me that I should switch direction and pursue a path more in line with my parents’ desires: law school. Already my father had plans for a father-daughter partnership.

“Sit down,” Fred said, his voice serious and without inflection.

I sat and stared down at my lap.

“I have some bad news,” he said.

I looked up waiting for the guillotine to fall.

“You’re a writer,” he finally said.

I let out my breath. Fred went on to tell me about a life of disappointment and likely destitution that lay in wait for me if I chose to follow this path, but also, a life of freedom and purpose and meaning that would follow, too. That he believed in my work—that I was the real and true thing. But all of this was predicated on whether or not I had the energy to back up my talent.

“Energy is everything,” he said. He meant the ability to work—to sit at the desk, day in and day out, and to get the words down, despite the disappointment and in spite of the success. Pushing on and pushing through, building sentence after sentence, page after page. Not turning away from the blank page, but always trying to build something from nothing.

I left his office that day knowing I was not a lawyer but a writer—this was the difference between being educated for a job and being seen, truly seen, for what I was. I left his office knowing I had suddenly gained a second father. My writer-father. Doesn’t every Irish Catholic girl from Queens want a Russian Jew from Brooklyn for a surrogate father?

From a letter Fred wrote to me over eighteen years ago:

Yesterday, walking the dogs down the road, I stood across from a swamp at the edge of my land and watched the formations of ducks taking off and landing—migration rumbling in them—and they flew so low above me that I heard the squeaking whistle of their wings. It suddenly occurred to me, I who had so envied birds their freedom from gravity, that flying is hard work. So is writing, which seems to be what I am about these days—a book impossible for me to write, which I write at every day.

Every day. Fred was always insisting that he had to earn his keep through a diligent duty to his writing. And his definition of good language? Words that were useful to someone other than himself.

Fred’s stories were often about the ways in which the hearts of his characters were warped, broken, and occasionally mended. His characters were trying to be good but usually fell short of their own expectations. His world, usually upstate New York, was the domestic world, populated with plumbers, teachers, security guards, and dog owners, but mostly families overrun by the lives they’d taken on. Basements flooded, sump pumps broke, blizzards hit, and, of course, husbands, wives, and children died.

Within his stories, Fred often offers truth statements that serve as centering theses. In “Widow Water,” a plumber must know “how to make a dead well live.” In “Family Circle,” one needs to know when “it’s time to lay claim.” In “Ralph the Duck,” the dog reminds us, after eating the deer carcass, that “He loved what made him sick.” In “Reruns,” the husband remarks, “We are so far from every place.” In “What You Might As Well Call Love,” Ben says, “The World will be fine,” and Marge responds, “Can you promise me that? Can you promise?” In the story, Ben is only able to give a half-hearted promise. This is in keeping with Busch’s vision and understanding of the world that he translates onto the page—a world of pain and brokenness, a world of forgiveness and redemption, a world of love and longing. The promise can never be kept.

Within his stories, Fred often offers truth statements that serve as centering theses. In “Widow Water,” a plumber must know “how to make a dead well live.” In “Family Circle,” one needs to know when “it’s time to lay claim.” In “Ralph the Duck,” the dog reminds us, after eating the deer carcass, that “He loved what made him sick.” In “Reruns,” the husband remarks, “We are so far from every place.” In “What You Might As Well Call Love,” Ben says, “The World will be fine,” and Marge responds, “Can you promise me that? Can you promise?” In the story, Ben is only able to give a half-hearted promise. This is in keeping with Busch’s vision and understanding of the world that he translates onto the page—a world of pain and brokenness, a world of forgiveness and redemption, a world of love and longing. The promise can never be kept.

“Words of integrity from a person with integrity,” Fred said. “That’s all I expect from you.”

It was the end of my senior year and we were talking about what I should expect from the MFA program in fiction that I was going to start in the Fall. I went in for a primer on how to survive the creative writing program, and I came out with a primer on how to conduct my life. Even today, whenever I feel myself getting lazy or tired in my writing, when I want to skirt a scene, when I want to substitute words because I can’t remember the exact ones I want, when I don’t push my characters hard enough in dialogue because I don’t yet know what they’re supposed to say, I hear Fred saying to me, “Words of integrity from a person with integrity,” and I can’t fail him. Not in the way I write, not in the way I live out my life.

Though Fred may be dead, he has been living with me, a voice steering me forward. “Integrity!” he says. “Energy!” he says. I live with Bipolar Disorder, and it is very often Fred who (imaginatively) speaks to me and helps me through pretty awful downslides—when my illness is out of control and I am acutely suicidal. I imagine him speaking to me in that clear, direct way he had—telling me it is okay to take a time out, that my talent will be there when I gather my forces again, that my energy will return, because it is important to keep my family together. (He knew something about the importance of family—he so desperately loved his wife and two sons.) The Writing Life would all be waiting for me again once I heal, so there is no need to be afraid. He is right. He always is. Just recently, he came to me in a dream. I was sitting with him at a long seminar table again, and he was chiding me for wasting too much time on nonessentials—laundry, frivolous reading, fretting about dog hair collecting all over the house, petty arguments, the minutiae of the mind—and not spending enough time on the writing, the work that mattered. Right again.

In A Dangerous Profession: A Book About the Writing Life, Fred writes:

Fiction that matters, of course, cannot be about living happily ever after. Serious writers don’t, I think, believe in it—although they might keep wanting to. Serious writing is about the trail of lifesaving breadcrumbs that are eaten by the forest birds. It is about being disposable. It is about what you say to yourself even if you have defeated the terrible darkness of nighttime in the forest, or the witch and her oven, or the dangerous, unmapped distance that separates you from home. It is about living a truth you’ve discerned but don’t want to know. It is about hunger, how hunger comes first.

For a wedding gift, Fred gave my husband and me four Tiffany crystal snifters. An extravagant, absolutely adult gift. He went off-list. Sheets and towels and spatulas might be practical, but the celebratory scotch on the occasion of a publication? Essential. His marriage, to his wife Judy, seemed a true wedding of funny, old souls, and in workshop, Fred was always, “Judy this,” and “Judy that”—he didn’t leave her out of his writing life. She was part of what gave shape and meaning to the words and sentences and stories that he laid down on the page.

And so years later, on a wintry night in my own home, my father was visiting. This was a year or so after Fred had died. And my father had had a scotch or two in one of those beautiful snifters, and as fathers are apt to do, he drifted off in the armchair, leaving the snifter precariously balanced on the edge. What you imagined happened happened. He shifted in the chair. I heard the tinkling crash from a distant room and came running, knowing already that the glass was broken. For a moment, I was in a mute rage at my father—How could he? Didn’t he know that this was a piece of Fred? But he couldn’t know. This was just a delicate, pretty glass like so many we already owned in our cabinet and he was sheepish and sorry. As I swept up the glass, all I could think was: Never again, I’ll never get a gift from Fred, my other-writer-father. Never hear the kind timbre of his voice telling me he believed in me, not just in my work, or my talent, but in me. But I was wrong, wasn’t I? And though this set of four glasses will remain at three, I reap his gifts every day and hear him speaking to me as if he was still here, saying as he so often did, “Be brave. Don’t be afraid to take on the difficult work.”