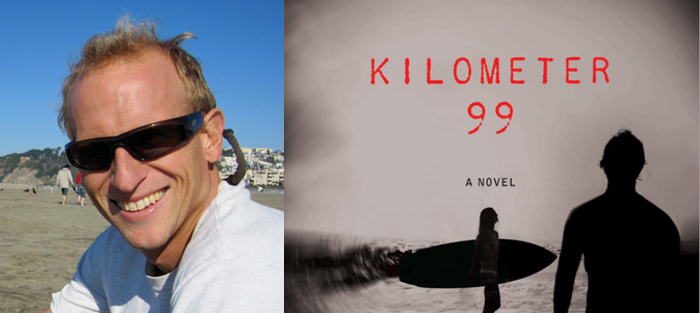

Memorial Day has passed, and the school year just ended, which means a certain kind of list is upon us: Best Books for Summer. One book that should be on everyone’s list this season is Tyler McMahon’s new novel, just out from St. Martin’s Griffin, Kilometer 99—a surf-fueled adventure story that is filled with heart and heartbreak. Kilometer 99 follows Malia, a twenty-three-year-old Peace Corp volunteer in El Salvador, and her relationship with Ben, a fellow Peace Corp volunteer and surfer. When an earthquake devastates much of the country, Malia and Ben decide to reroute their lives and make plans for an epic surf odyssey down to Chile. Before they can leave, however, Malia and Ben will first have to deal with petty thieves, drug runners, a sketchy realtor-slash-surfer named Pelochucho, and rumors of monster swell.

Though it’s full of adventure, Kilometer 99 isn’t superficial. McMahon uses the larger storyline to skillfully explore topics as sweeping as the Salvadoran Civil War, the practical constraints of aid work, and the Hawaiian word kuleana, a word that resists direct translation but speaks to the ideas of personal responsibility and stewardship. Kristiana Kahakauwila, author of This is Paradise, praised Kilometer 99, noting its “immediacy, ferocity and a deep sense of place,” and Katie Arnoldi, author of Point Dume, called it “the best surf novel of the 21st Century.”

McMahon was born and raised in the Washington, DC area. He studied at the University of Virginia and Boise State University. In addition to Kilometer 99, he is the author of How the Mistakes Were Made, a novel Jonathan Evison tagged as “un-put-downable.” McMahon lives in Honolulu with his wife, food writer Dabney Gough, and teaches in the English Department at Hawaii Pacific University. In addition, he’s the editor of Hawaii Pacific Review.

I was first introduced to Tyler in 2005 when he published a short story of mine in the now-defunct literary journal Cold-drill—a story that would become the opening piece to my first book, Close Is Fine. At the last AWP, we shared a beer, but now I can’t remember who bought. In this interview, which took place via email over the course of about a week, I ask Tyler about the challenges of writing about surfing, the real-life events that inspired his novel, and the most important advice he’d give a young writer.

Interview:

Eliot Treichel: Though Kilometer 99 is more than just a surf novel, I wanted to start there—with surfing. I grew up as a whitewater kayaker, but for a long time I resisted writing about whitewater paddling because it felt nearly impossible to translate such a physical, fluid, sensate experience onto the page. For me, whitewater kayaking was almost too ephemeral or private to capture, though that’s changed a bit as I’ve gotten to be a better writer. In Kilometer 99, the surf scenes are incredibly well rendered, and you do a terrific job of putting the reader right there on the waves with Malia and Ben. I’m wondering if you could speak to some of the challenges you encountered while trying to write about the actual act of surfing.

Tyler McMahon: Writing the surfing scenes terrified me. I worried about pushing readers away—writing passages that would only connect to surfers and not to the larger audience. But the bigger concern was just what you describe: the inability to translate such a physical sensation onto the page. I felt this same hesitation in my first novel, when writing scenes of musicians playing live. In a sense, the whole point of sublime experiences is to make you escape your descriptive and critical facilities. So it feels counterintuitive to write about those experiences.

Tyler McMahon: Writing the surfing scenes terrified me. I worried about pushing readers away—writing passages that would only connect to surfers and not to the larger audience. But the bigger concern was just what you describe: the inability to translate such a physical sensation onto the page. I felt this same hesitation in my first novel, when writing scenes of musicians playing live. In a sense, the whole point of sublime experiences is to make you escape your descriptive and critical facilities. So it feels counterintuitive to write about those experiences.

I never had a deliberate strategy for dealing with this challenge, but there were a few things I stumbled onto. For one thing, most of the times that Malia and Ben are in the water, the waves are not particularly good. Partly that’s for contrast, to make the big days that much bigger, but it also kept me from waxing philosophical about the perfect surf session too often. Another thing I did—and this is an approach I’ve taken to writing sex scenes, as well—is to focus on the minutia. In a lot of the surf passages, Malia focuses on the sounds in the background, the other people in the lineup, what the wind is doing, and so on. I try not to think about summing up the act in general, so much as making this one particular act convincing.

There’s also a sort of long-term accumulation at work. I feel like I’ve been informally collecting little bits of surfing descriptions and insights—in stories or letters that I’ve written, things I’ve overheard or imagined. In a way, this novel was an opportunity to draw on that internal catalog. That’s one advantage that a novelist has over other kinds of writers, who might have to cover one subject repeatedly.

It’s been a big relief that early readers (such as yourself) have responded favorably to that material. I didn’t start surfing until I was in my twenties, and I didn’t move to a coast full time until I was in my thirties, so I’ve always felt partly like an outsider to the sport. Perhaps that helps me describe it, to some extent.

One of my favorite books ever is Daniel Duane’s Caught Inside (North Point Press, 1996), a nonfiction book that details a surfer’s year on the California coast. One of the most striking aspects of that book for me, along with how Duane captures surf culture, is how the author articulates the intimate sense of place that surfing seems to necessitate. Could you talk a little about this link between surfing and sense of place, especially in a novel that is set in both real and imagined locations?

Dan Duane is one of the best writers ever to take on surfing as a subject. I’ve long admired his work, as well.

Dan Duane is one of the best writers ever to take on surfing as a subject. I’ve long admired his work, as well.

My novel absolutely started with a place: Puerto La Libertad, in El Salvador. Everything else—the characters, the plot, the style—were all altered during the course of writing it.

My interest in that city is certainly rooted in surfing. Through most eyes, La Libertad in 2001 might’ve looked something like a dystopian nightmare: a mix of crime, pollution, heat, drugs, and poverty by the sea. But to a surfer, it was absolute paradise. That’s the central paradox that drives the book. The city was a bit like the ocean itself, capable of great destruction or great fortune depending on its mood.

As far as the imagined locations, I consider them mostly a matter of narrative convenience—a compression of real locations, with a few details manipulated. There’s a real surf break called Kilometer 59 in El Salvador, upon which Kilometer 99 is based. I culled its other aspects—the hamlet of landowners eager to sell their property, and the way that drug traffickers used it to land their cargo—from other surf breaks in El Salvador or elsewhere in Latin America.

It’s funny, because I’ve never thought of myself as much of a “place-based” writer, partly because I grew up somewhere that seemed unremarkable: not quite urban and not quite rural, in between the north and the south, with average weather and geography. I’m sometimes jealous of writers who have a particular locale that they return to over and over again. It was nice to work on a project like this, for which the setting was a starting point.

Let’s build off this idea of place and zoom out a bit from La Libertad. Arguably, the central plot element of Kilometer 99 involves a pair of deadly earthquakes that struck El Salvador in January and February of 2001. I imagine that, like me, there are many Americans who don’t even remember this, or who weren’t even aware that these disasters happened. As I understand it, you were working for the Peace Corps in El Salvador when those quakes hit. What was that experience like, and what’s been its lasting impact on you? What should people know about these earthquakes?

That’s exactly right. I was a Peace Corps volunteer in El Salvador in 2001, when those two destructive earthquakes hit within a month of each other. Many of the things that Malia experiences during the first quake are similar to what I went through.

The quakes made a major impression on me. One of the most lasting effects was distrust of the scientists and authorities involved. Right after the January 13th quake, they told us that there would be minor aftershocks for a few days, but nothing major. In fact, the aftershocks went on for weeks, many of them were quite large, and then an even more destructive quake hit on February 13th; the experts said the same thing. It wasn’t hard to tell that we were being placated. I still feel this way often, when listening to authorities. Every time I hear a pilot over a plane’s PA system, I assume I’m being lied to.

As much as I’d like to say that I never succumbed to any of the numerological or apocalyptical theories that circled through the countryside in those days, that would be untrue. It all felt very biblical.

Like Malia, I had a moment shortly after the quake in which I saw the water system I’d been working on for years turned to ruins. (In fact, my aqueduct ended up being easier to repair that it initially appeared.) So while I was distraught over the many dead, injured, and homeless, I also saw the futility of my work in full relief. It was humbling, more than anything else.

I think you’re right that most Americans wouldn’t remember those quakes. It was international news, but not for long. Also, it was followed in short order by such a tragic series of natural and man-made disasters (9/11 and its consequences, Hurricane Katrina, the Indonesian tsunami, etc.) that it often feels quite inconsequential.

An interesting subplot that emerges in the novel is the difference between development work and relief work and the money associated with each. After the first quake, once the focus shifts to relief work, Malia witnesses all sorts of money and equipment flowing into El Salvador, whereas before, with her development project, that kind of assistance was much harder to secure. This disparity is something Malia and a few other characters really struggle with. How have your thoughts on these issues evolved over time?

Towards the end of my time in Peace Corps, some of the best and brightest of my fellow volunteers were recruited for relief work in Afghanistan. I remember being jealous of them, and cloaking my envy in the notion that development was superior to relief. As I recall, the development camp liked to say that relief workers were in the business of “delivering groceries.” It’s basically the give-a-person-a-fish vs. teach-a-person-to-fish idea.

In the novel, I may have painted the distinction as more black and white than it really is—in order to force circumstances to change under Malia’s feet. In truth, these two kinds of work often bleed into each other, and many of the same personnel go back and forth between them. However, I do think that relief is more related to the headlines and the zeitgeist, and certainly more prone to bigger budgets and shorter timelines.

As far as how my views have evolved over time, I certainly no longer feel entrenched on either side (if I ever truly did). It’s too easy to be cynical about both efforts. As the character of Alex says at one point, human beings once did charitable works for spiritual reasons—for penance or enlightenment. Changing to a more practical, results-oriented model will take time.

It’s clear the earthquakes have a humbling effect on Malia, as well. By the end of the novel, she’s transformed. She’s an interesting character and an interesting P.O.V. choice, one that drew me in completely. Tell me a little about her. Did you always know she’d be the narrator? In what ways did she surprise you as you worked on this book?

I didn’t always know that she would be the narrator, or even that she’d exist at all. For years, I struggled to write a story of some kind about some volunteers-turned-surfers in post-earthquake La Libertad. Initially, I wanted it to be two male friends, and have the narrator’s female love interest stay behind to help rebuild (the way that Alex does now). But it never worked.

The idea of having a female narrator—and a bit of a love triangle to reflect her indecision—occurred to me one day. I saw the appeal of it, but I was hesitant to try it out. (My first novel was narrated by a woman, and I worried about it looking like a gimmick.)

Shortly thereafter, I realized that a woman from Hawai`i, with closer knowledge of tourism and colonialism and such, would have an even more interesting take on the story. This also scared me. Even though I’ve lived here for much longer than I lived in El Salvador, writing about Hawai`i gives me pause. Outsiders have trafficked in images and stories of Hawai`i for a long time, and I was hesitant to be a part of that. But in the end, I got over my fear and gave it a try. Right away, Malia snapped the story into focus. As soon as I started writing in her voice, it was clear to me that she had to tell the story.

I wanted to ask this earlier, so I guess I’m going to just wedge it in here: We already talked about Daniel Duane’s Caught Inside. What are some other titles in the surf literature canon that you’d recommend to readers?

One of my all-time favorite surf books is In Search of Captain Zero, by Allen Weisbecker (Tarcher, 2001). It’s sort of a memoir/travelogue/real-life detective story. It contains one of the few written accounts of the La Libertad surf scene in the era in which my novel is set, and gets it perfectly right. Weisbecker captures the things about surf culture that interest me. He’s not into big waves, or even perfect waves, so much as the alternative lifestyle aspect, and experience of dropping out and surfing without distraction.

The series that William Finnegan did for the New Yorker years ago—about Doc Renneker and the Ocean Beach surfers—is terrific. I also like the Kem Nunne novels; Point Dume, by Katie Arnoldi (Overlook, 2010); and Stuart Holmes Coleman’s books about Hawaiian surfers: Eddie Would Go (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2004) and Fierce Heart (St. Martin’s Press, 2009).

Lastly, this: you currently teach at Hawaii Pacific University. Let’s say a young Tyler McMahon shows up in one of your classes. From where you’re at now—a little older, a little wiser, with two novels out in the world—what’s the most important piece of advice you give him about writing?

You know, I was back in Boise, Idaho, a couple of months ago—where I went to grad school. One of my former classmates mentioned that all the life/career advice we received from creative writing teachers could be distilled down to this message: it’s totally ridiculous to pursue this, but if you quit then you’re a coward.

You know, I was back in Boise, Idaho, a couple of months ago—where I went to grad school. One of my former classmates mentioned that all the life/career advice we received from creative writing teachers could be distilled down to this message: it’s totally ridiculous to pursue this, but if you quit then you’re a coward.

I hope I can offer my students something a little less bleak. I suppose the lesson that I learn over and over again is that the best reason to pursue creative writing is if you truly enjoy it.

I understand that writing is hard work and often frustrating and so on, but I think there should be a net pleasure. For me, I now enjoy the hours I spend at my desk—with a blank page or a word processor—more than ever before. At this point, it’s clear to me that this is the only part over which I have complete control. It has to take center stage.

For the vast majority of us, writing novels is never going to be a means to an end, so it’s important to find pleasure in the process. Lately, I’ve been trying to maximize the parts I enjoy and minimize the parts that depress me. Though I suppose that’s more difficult for somebody who’s just starting out.

What’s the chance he listens?

I’ve found that most of my students are like I was as an undergraduate: excited about writing, eager to pursue it, but not so interested in the real-life implications. I don’t think that’s a bad thing at all. In fact, I try not to spoil their enthusiasm with careerist concerns. I often wish I’d saved a bottle of the excitement I used to feel as a student at public readings, or during writing exercises, or with a book that connected to me.

Honestly, I believe that my students’ generation is a probably better suited to a world in which writing novels is more like a hobby than a job. I think I suffered from the delusion that, in order to be serious about writing, I had to pursue it at the expense of other things. The young people I work with nowadays have a greater breadth of interests and talents. I look forward to seeing where the literary world goes, once it’s in their hands.