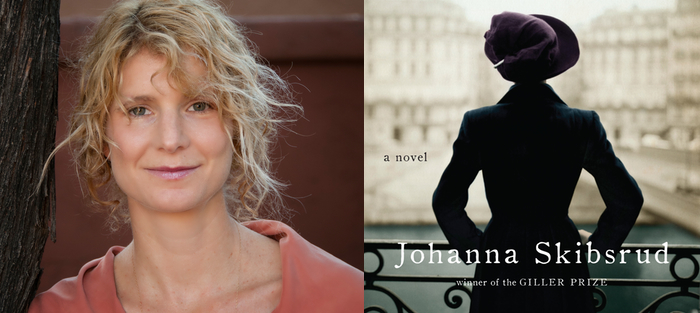

Johanna Skibsrud was born in Nova Scotia in 1980. She earned her MA in English and Creative Writing from Concordia University, and her PhD in English Literature at the Université de Montréal. Her first novel, The Sentimentalists (W.W. Norton & Company, 2011), won the Giller Prize, and her story collection, This Will Be Difficult to Explain and Other Stories (W.W. Norton & Company, 2012), was shortlisted for Canada’s Danuta Gleed Award. She is also the author of the poetry collections Late Nights With Wild Cowboys (Gaspereau Press, 2008), which was shortlisted for the Gerald Lampert Award for the best first book of poetry by a Canadian poet, and I Do Not Think That I Could Love a Human Being (Gaspereau Press, 2010), which was short-listed for the 2011 Atlantic Poetry Prize. She is currently an Assistant Professor of English at the University of Arizona.

Her new novel, Quartet for the End of Time, was published this fall by W.W. Norton & Company in the U.S., Penguin in Canada, and William Heinemann in the UK. The book tells the story of four people whose lives are forever changed by political and historical mechanisms beyond their control. This is a cinematic, globetrotting novel that transports us from the Bonus Army Riots in Washington D.C. to Roosevelt’s labor camps in the Florida Keys, and from underground Soviet spy rings to a German prison camp. I completely lost myself in this novel—it manages to be both a grand, historical page-turner and a compassionate analysis of faith, memory, responsibility, and consequence.

Johanna and I corresponded over email about her research process, the challenges of writing historical fiction, and the piece of music that inspired this book.

Interview:

Molly Antopol: One of the things I admired most about this book was how seamlessly you wove in the relationships between art and politics, history and war. Did you set out to write about these themes, or did they emerge naturally through the drafting process? In other words, what initially inspires you: character, plot, theme, or something else entirely?

Johanna Skibsrud: This book began with two major—and quite different—inspirations. The first was learning about the Bonus Army March of 1932, and the second was Olivier Messiaen’s chamber music piece Quartet for the End of Time, for which my own book is named. But it wasn’t the Bonus March or Messiaen’s composition in and of themselves that inspired me—it was the many questions I saw surrounding both events; the way that each opened off onto so many other stories. With the Bonus Army, my fascination was primarily with why I hadn’t heard of the event before. I stumbled on a reference to it only in 2008, and with the concurrent housing market crisis it got me thinking about the imaginary aspects of our reality—financial, social, and political—which the “Bonus” of 1932 seemed to so eloquently express. I also wondered: Why are some stories told and retold, and some are—to greater and lesser extents—forgotten? How is history shaped in this way, and how are we more or less complicit in this process? With Quartet for the End of Time, it was the willful intersection of consonance and dissonance in the music, as well as the story of its creation that grabbed me. Messiaen first wrote and performed the piece in 1941, in a German prisoner of war camp. I wondered: How does beauty arise from—or, rather, get perceived from or within— chaos? How does consonance arise from or within dissonance? Meaning from or within what we cannot, indeed do not wish to, understand? At the time that the Messiaen’s quartet was first performed, there was some controversy among the musicians as to whether participating in the performance of this incredible piece of music (which Messiaen insisted vehemently existed quite outside, or above, questions of politics and war) was a form of collaboration with the enemy. With my novel, I wanted to think about the limits of responsibility, and the line (if indeed it exists) that we imagine between art and politics—as well as between the past, the present, and the future. The characters and the plot grew out of my desire to try to explore these many questions and ideas, but I don’t think of them as separate or auxiliary somehow. They aren’t—I hope— vehicles for ideas, but are the very ideas themselves.

Johanna Skibsrud: This book began with two major—and quite different—inspirations. The first was learning about the Bonus Army March of 1932, and the second was Olivier Messiaen’s chamber music piece Quartet for the End of Time, for which my own book is named. But it wasn’t the Bonus March or Messiaen’s composition in and of themselves that inspired me—it was the many questions I saw surrounding both events; the way that each opened off onto so many other stories. With the Bonus Army, my fascination was primarily with why I hadn’t heard of the event before. I stumbled on a reference to it only in 2008, and with the concurrent housing market crisis it got me thinking about the imaginary aspects of our reality—financial, social, and political—which the “Bonus” of 1932 seemed to so eloquently express. I also wondered: Why are some stories told and retold, and some are—to greater and lesser extents—forgotten? How is history shaped in this way, and how are we more or less complicit in this process? With Quartet for the End of Time, it was the willful intersection of consonance and dissonance in the music, as well as the story of its creation that grabbed me. Messiaen first wrote and performed the piece in 1941, in a German prisoner of war camp. I wondered: How does beauty arise from—or, rather, get perceived from or within— chaos? How does consonance arise from or within dissonance? Meaning from or within what we cannot, indeed do not wish to, understand? At the time that the Messiaen’s quartet was first performed, there was some controversy among the musicians as to whether participating in the performance of this incredible piece of music (which Messiaen insisted vehemently existed quite outside, or above, questions of politics and war) was a form of collaboration with the enemy. With my novel, I wanted to think about the limits of responsibility, and the line (if indeed it exists) that we imagine between art and politics—as well as between the past, the present, and the future. The characters and the plot grew out of my desire to try to explore these many questions and ideas, but I don’t think of them as separate or auxiliary somehow. They aren’t—I hope— vehicles for ideas, but are the very ideas themselves.

Like Messiaen’s composition, your book is divided into eight parts. Is there a story behind this?

Messiaen’s goal was to be able to transcribe the sounds of the world around him (everything from birdsong to the sounds of engines and guns) into music. My (equally ambitious, equally ultimately unrealizable) goal was to transcribe the questions and ideas surrounding his music into words. I tried to mirror the structure of Messiaen’s quartet (itself structured by scenes and passages from the Book of Apocalypse), but I didn’t conceive of this as a constraint. More the opposite: I used the structure as a point of departure for my own exploration into the complex themes and emotions that surface through listening to, and thinking about, Quartet for the End of Time. I did think very seriously and literally, though, about how I would present the “interlude.” What could an “interlude” in a novel really be? I wanted to find a way of getting outside of words, even though this is not what a musical interlude does (it does not, that is, escape its own medium, leaving music behind). What I settled on—including images within the book that speak more or less obliquely to the novel’s plot and characters—does not, in the end, escape language either. I think of my “interlude” now, instead, as a way of zeroing in on a particular element of language—the image—in the same way that different musical phrases can tune our ear to particular elements of music, of sound, or of the act of listening itself.

You narrate the book through multiple characters’ points of view. Is this choice of perspective something you found yourself particularly drawn to, or did you feel that the story you wanted to tell had to be told this way?

There are four distinct voices in this novel, as I see it. For me, this is another way of echoing, or responding to Messiaen’s Quartet—which, of course, is also a conversation among four voices. The story is told through the alternating perspectives of Sutton Kelly, Alden Kelly, and Douglas Sinclair. The voice of Arthur Sinclair (Douglas’s father) is the missing fourth voice. All of the rest of the voices revolve around this one—are always, to greater or lesser extents, searching after it. Without this missing fourth voice (i.e., the conception of silence), there would be no rhythm, no music, or story—no time.

I read in an interview that you find yourself drawn to telling stories that would otherwise “remain either swept under the rug or rarely mentioned, if discussed at all. ” Can you speak to that idea, both as a reader and as a writer? Are there other books and authors that do this who have inspired you?

I read in an interview that you find yourself drawn to telling stories that would otherwise “remain either swept under the rug or rarely mentioned, if discussed at all. ” Can you speak to that idea, both as a reader and as a writer? Are there other books and authors that do this who have inspired you?

I think that to a certain, very important extent that is what all stories do: shape how and what we remember. Good storytellers are not those who stumble upon content that is inherently interesting or important, but those who detect and essentially create what is interesting and important. They draw our attention to what we might not otherwise understand as our own experience. I think of writers like Marcel Proust, Virginia Woolf, or David Foster Wallace, who train their attention on minute elements of our emotional lives that we might not otherwise even notice, let alone interrogate. Or writers like Doris Lessing, Thomas Pynchon, Thomas King, or Madeleine Thien, who draw our attention to aspects of our past or our present that we are often afraid to look in the eye.

Something I loved about this novel is how self-aware and questioning all of your characters are. As a writer, you seem to be unafraid of epiphany. I really admire that, and it’s something I think a lot about in my own work. I’m wondering whether you knew how your characters would react in key moments before you started writing, or whether those realizations were as surprising for you, as a writer, as they were for your characters.

Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time was based, as I said, on the Book of Apocalypse. Specifically, the scene where the Angel of Apocalypse places one foot on the sea and the other on the earth, and declares “there shall be time no longer!” Apocalypse, in its more original sense, means “revelation”—as does epiphany. I think that is what writing is really about. It’s a process of uncovering. What’s underneath language and ordinary, unexamined experience? How do we create history and meaning? Who are we? To shy away from epiphany (in writing or in life) is to shy away from the real strength of human thought and experience. Epiphanic moments in literature can be done badly, of course. If they aren’t earned, they can feel flimsy or insincere. But everything can be done badly … that’s the risk of attempting anything difficult or sincere. You can fail horribly. But that’s not really a very high price to pay, considering what can be gained if you happen to succeed!

History—be it political or personal—seems to shape this book on almost every level. What is it about the past that intrigues you as a writer?

History is all we really have as writers, and as human beings. I like to read literature set in the future, and sometimes I like to write it, but even that is still essentially historical in terms of its inspirations and structure. It is still indebted, and bound to, the past. One of the main images in my first novel, The Sentimentalists, is a town submerged by water after a hydroelectric dam moves in. The whole novel really emerged from a small “epiphany” I had one day while canoeing over a town that had been similarly submerged. The past doesn’t just disappear. Just as water level is affected—is, indeed, achieved—by whatever exists, invisible, beneath the surface, the present is created from the materials of the past. That these materials are often invisible or forgotten does not make them less integral to the structure of our present moment.

Speaking of history, can you take us through your research process for this novel? In addition to the Messiaen piece, were there other art forms—film or books or something else—that particularly inspired you when writing this novel?

There are so many inspirations for this novel, I can’t begin to name them all. Not only for lack of space, but because many are just so impossibly absorbed by now. My main sources (for historical material, atmosphere, or driving concerns) are listed at the back of the book, and include: James Agee and Walker Evans’ Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, John Gray’s The Immortalization Commission, Library of America’s Reporting World War II, George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia, Irene Nemirovsky’s Suite Francaise, John William McMullen’s The Miracle of Stalag VIII-A, Ewen Montagu’s The Man Who Never Was (also a film), Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, and The Book of Revelation, verse 19.

There are so many inspirations for this novel, I can’t begin to name them all. Not only for lack of space, but because many are just so impossibly absorbed by now. My main sources (for historical material, atmosphere, or driving concerns) are listed at the back of the book, and include: James Agee and Walker Evans’ Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, John Gray’s The Immortalization Commission, Library of America’s Reporting World War II, George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia, Irene Nemirovsky’s Suite Francaise, John William McMullen’s The Miracle of Stalag VIII-A, Ewen Montagu’s The Man Who Never Was (also a film), Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, and The Book of Revelation, verse 19.

What are the books that first inspired you to write? Which writers do you turn to now?

I started writing at a very young age, so my first inspirations were probably Gabrielle Vincent, Dennis Lee, L.M. Montgomery, Louisa May Alcott, and Rudyard Kipling. Later, it was writers like Virginia Woolf, Knut Hamsun, Marcel Proust, and Vladimir Nabokov that exploded my notion of what fiction could do. More recently, Olaf Stapledon, Clarice Lispector, Inger Christensen, and Ferdinando Camon have inspired me in a similar way.

Finally, the question I find so challenging to answer myself but am just too curious not to ask you: What are you working on now?

I’m working on a collection of poetry, which will come out in 2016, through Wolsak and Wynn, a collection of short stories, and a novel. In contrast to Quartet, the novel I’m working on now takes place—refreshingly—over a period of just twenty-four hours.