I was first introduced to Jacob Paul’s work by Erika Dreifus, whose review of his debut novel, Sarah/Sara, appeared here on Fiction Writers Review in July of 2010. The introduction to that review begins:

Jacob Paul’s debut, Sarah/Sara, is not a joyful read, but it is a deeply moving one. The novel unfolds as the journal of Sarah Frankel, an American-born Jew who, shortly after finishing college, moved to Israel, where she took the Hebrew version of her name (“Sara,” pronounced Sah-rah) and became far more ritually observant than she was raised to be. After her visiting parents are killed in a suicide bombing in the café below her Jerusalem apartment, Sara embarks on a six-week, solo kayaking trip through the Arctic. Throughout the beautiful yet dangerous trek, Sarah’s thoughts turn not only to her past—memories—but also to an imagined future, one that challenges her faith.

The following year, we published Aaron J. Cance’s interview with Jacob, which also focused on Sarah/Sara. In both features, I was struck by the way in which this book and its author seemed preoccupied with the intersections of faith and healing, endurance and belief, and how one makes (or, tries to make) meaning from the unknowable and inexplicable.

In 2011, I met Jacob in person at AWP. And in the following years we’ve kept up a conversation of sorts, working together on Jacob’s critical and essayistic work he’s published on this site, and continuing our discussions from one conference to the next. Throughout the process, I’ve learned a lot about philosophy, about critical theory, and about the deeply challenging and problematic work of tackling a subject like the holocaust in fiction. (Read Jacob’s marvelous essay “Slouching Past Totality; Or, What a Post-Postmodern Holocaust Novel Might Look Like” for a glimpse.) I’ve also come to greatly admire Jacob’s empathy for his subjects, and the joy he manages to bring to his exploration of their worlds, despite the often fraught terrain he is covering.

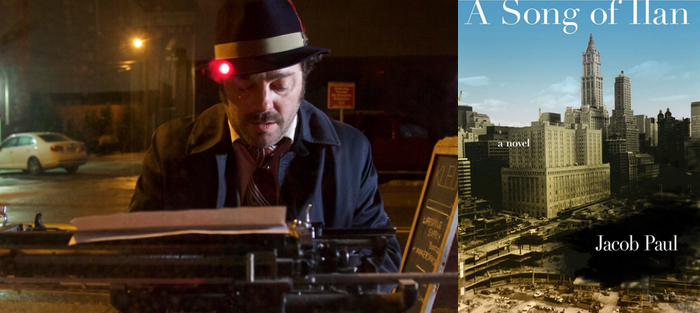

So it was a pleasure to finally sit down with him to talk about his work, both Sarah/Sara and his newest novel, A Song of Ilan (Jaded Ibis Press, 2015), which revolves in part around the chain of events set in motion by the guilt the title character feels after shooting a female suicide bomber in Tel Aviv during his mandatory military service in Israel. Returning to the U.S. following the incident, American-born Ilan finds himself destabilized by the occurrence, and the novel seeks to unravel his unraveling. It does so in a narrative that is equally destabilized, offering the reader alternative ways in to the story and to the pathos at the heart of this deeply felt book.

In addition to producing these two novels, Jacob’s collaborative work based in the Social Practices in Art movement has led to several projects and books, including, Home for an Hour (MPMP, 2014). He holds an MFA from the Vermont College of Fine Arts and a PhD from the University of Utah. He currently teaches creative writing at High Point University in North Carolina. For more on Jacob Paul and his work, visit his author site.

Interview:

Each of your novels grapples with the meaningfulness of acts and gestures. I’m thinking of the very opening of Sarah/Sara, where, in the first couple of pages, she writes in her journal, speaking (in a sense) to her dead father: “I’m finishing your dreams for you. I have to believe you can see that.” It’s that second sentence that was most important for me, as regardless of whether there’s one to do the witnessing or not, one still enacts the act as if that were the case, because it’s the action itself that’s giving the meaning to the thing. Does that make sense?

Yeah. Right. Given these kinds of choices, we end up all having to find the “even though” phrase that then guides what we do. And maybe the question that’s becoming more interesting to me that begins to percolate in Sarah/Sara and A Song of Ilan, and is more pronounced in the third book I’ve worked on, is that there does come the moment when you have to ask, “How far does one want to take the warrant for one’s actions from people who are dead on the premise of understanding what it means that they have died?” That becomes really extensible. To what extent does Sarah have to continue to complete her dad’s dreams? Does she need to complete her dad’s dreams? Why would that be the thing to do even at some point?

One of the things it occurs to me has transpired is that much of contemporary Jewish identity is based upon the fact that there was a holocaust. But that becomes it’s own really dangerous trap, to tie one’s ethos to something one wishes wasn’t done, and not just wishes wasn’t done, but wishes wasn’t done several generations ago. I don’t think it’s a good idea for Jews to choose to be identified, first, as the children of the Holocaust, still. It’s especially problematic as it begins to license behavior that would otherwise conflict with the core of Jewish identity, or international norms, or moral norms, or all of these. This isn’t to disavow the Holocaust, or its impact, or any other individual trauma one finds foundational to their identity; rather, we need to be mindful that the continuing to identify ourselves in those terms is also a trauma, and potentially one that creates new traumas.

And so that’s working its way into your third book?

The third book I’m pretty close to finished with, but yes. I feel like the three novels all thematically build upon each other. And I feel that with the third one, that particular inquiry is done. I don’t think there’s a fourth book in that vein. I think this is a trilogy, thematically. In that third book, the conceit is that the protagonist realizes he exists in the dream of a person who’s being gassed to death in the Holocaust. But he lives in our world. And he tries to figure out what to do with this information. First, he thinks he’s going to exist in a narrative that looks like magical realism, but he doesn’t, and the fact is that he can’t do anything. But this is his authorizing principal, so what is he supposed to do with it? And the book covers—I think it’s an eighteen-year span I give him—the ways in which he tries out different approaches to the same problem.

Another element that intersects much of your work is that of “doubleness”—this idea of “the other,” the doppelganger,” or different versions of one’s self. In Sarah/Sara, the protagonist expresses this explicitly. Near the end, she says: “It occurred to me, not for the first time, that perhaps there are two of me: the me that wants to live, and the me that quickly sabotages my choices of doing so, me the victim and me the terrorist.” It feels as though those lines could have been spoken by Ilan, as well—those exact sentences. So, can you talk about your interest in the idea of the uncanny double or the other?

Yeah. I feel tempted to turn to Giorgio Agamben again, just because I’ve been reading him, and this notion that’s been haunting me. [Looks for passage in book.] This is early in his book, in his first chapter, in Section 3. Under “The Witness,” he writes:

In Latin there are two words for “witness.” The first word, testis, from which our word “testimony” derives, etymologically signifies the person who, in a trial or lawsuit between two rival parties, is in the position of a third party (terstis). The second word, superstes, designates a person who has lived through something, who has experienced an event from beginning to end, and can therefore bear witness to it. It is obvious that Levi [Primo Levi, that is] is not a third party, he is a survivor, [superstite] in every sense. But this also means that his testimony has nothing to do with the acquisition of facts for a trial (he is not neutral enough for this, he is not a terstis). In the final analysis it is not judgment that matters to him, let alone pardon.

Then he’s quoting Levi as saying, “I never appear as judge” ; “I do not have the authority to grant pardon…I am without authority.”

It seems, in fact, that the only thing that interests [Levi] is what makes judgment impossible: the gray zone in which victims become executioners and executioners become victims. It is about this above all that the survivors are in agreement.

“No group was more human than any another,” which was from Levi. “Victim and executioner are equally ignoble; the lesson of the camps is brotherhood in abjection.”

This idea begins playing out much earlier, in the nineteenth century, as a mode of looking…as equivocating between things viewed as binary, as a way of undoing an oppressive morality. I think that’s kind of the ambitions of Sade, or later Bataille, and maybe Nietszche in between. This stems out of, I think, our confinement of our thinking to a Hegelian dialectic setup, where we have these theses and antitheses as our choices, and we want to think them separate, but we think if we can undo their separation, we can undo other power structures. And that becomes much more problematic if we get into this later stage where Levi is writing that there’s no difference between victim and executioner, which seems prima faci in saying when we’re talking about the holocaust. But as soon as Agamben evokes that notion of “the abject” as a theoretical space, it begins to make more sense. To participate in the act, whether by choice or not, means to leave the space that isn’t abject. Meaning, you have to succumb to abjection in some way.

Where that becomes interesting to me in these kinds of doppelgangers is that on the one hand I sort of feel like the interiority of other people is radically unknowable—one can’t presume to understand other people’s motives; one must, out of a sense of compassion and humanity, but to make the claim to “know” those things seems arrogant and irreverant towards others. But then that leaves one with a hyper-interiority of the self, in which one’s own actions create the context, one’s own ordering principles become the context. And in the case of both Sarah and Ilan, they are their own terrorists and their own victims, their own executioners and their own victims. And this is different than the conflation of the survivors to the camps and the nazi guards. To be clear, I’m talking about a different thing. But in the legacy of action, the person becomes both things because it’s the consciousness that’s creating the trauma, which then becomes lived in the body, and then becomes enacted upon the world. As much as Sarah runs, she takes her crisis with her. She writes the future, and in her writing of the future from within herself she creates the fear on the bus. Ilan carries with him both the fact that he’s killed this woman and the fact that to kill this woman is to make himself a victim of the perpetration of violence.

I think what’s interesting to me about those things, though, too, is that internal doubling, that internal occupation of multiple roles that are in conflict with each another, that have different moral standing. If it’s purely an internal crisis, then we’re back to our garret where I’m drinking my jug of Carlo Rossi and I’m feeling really strongly about women who don’t know I exist and writing poems to them that they will never read. [Laughter.] But if we take this as the motivating consciousness within the individual who then has the ability to act materially in the world, then it becomes a very different kind of thing. You can go on a trip, you can build a bomb, you can go climbing, you can do things and these things are influenced by this internal doubling. And the desire to materialize that doubling seems, to me, a desire to escape the multiplicity of potential meaning, the way in which all those different translations at once give this tremendous three-dimensionality and are also incredibly confining. And if we can just know the denotative meaning, we no longer are confined. But maybe only one individual could know that, not all the versions of the self, either. So if you can make those other versions other people, you can kick them out. Then…that’s better. But to realize that they’re acting is to recognize them as the self.

Now I think I’m talking in circles. I apologize for that. [Laughter.]

No, no I think it’s fascinating. And what I’m equally intrigued by is the way in which recognition—particularly of doubling—serves as a kind of epipanic moment; the realization of the self as other, double, doppelganger. For example, Sarah’s recognition of that doubled self emerges where one would probably anticipate the conclusion of the book, for lack of a better description. And I wonder if there’s a similar recognition that occurs for you near the end of A Song of Ilan, the ending of which I think one can read as either very ambiguous or, well, quite final, to say the least.

More importantly though, I guess, was there a moment of recognition for you in writing these books where you thought: “Ok, that’s the story. Now the story can close, it can come to rest.” Regardless of whether that was the same moment for the characters.

So, the first thing I’ll say by way of aside is that I would say almost all of the readers who I’ve spoken to about Sarah/Sara who have come to me to talk about the book are not satisfied with my ending of that book. [Laughter.] They’re like, “What the hell happens to her?!”

Really?

In that book I’m totally chill, I’m like, “I got what I needed; I’m out.” [Laughter.]

These books are inquiries for me, they’re thinking processes. Once I reach the answer to the thematic question that I’m trying to work out through narrative action, whether it’s the question I realized I was asking or the question I discover I wanted an answer to, once that happens, I’m good. And I think for Sarah/Sara, for me…she makes a choice. For her, the recognition of that doubling is probably the opportunity to realize that she gets to choose on her own terms, because she’s going to be all of the characters, she’s going to be all of the forces, she’s internalized them. To give them a weight beyond that internalization is to give them an undue weight. And so she makes a choice, and the outcome of that choice is…well to answer that choice, I not only have to start asking questions about physics and reality and what would actually happen to a woman walking across the ice hauling a sled, but I would have to care, and I find myself asking, do I care? She’s a fiction. But the choice she’s makes, that isn’t a fiction for me.

These books are inquiries for me, they’re thinking processes. Once I reach the answer to the thematic question that I’m trying to work out through narrative action, whether it’s the question I realized I was asking or the question I discover I wanted an answer to, once that happens, I’m good. And I think for Sarah/Sara, for me…she makes a choice. For her, the recognition of that doubling is probably the opportunity to realize that she gets to choose on her own terms, because she’s going to be all of the characters, she’s going to be all of the forces, she’s internalized them. To give them a weight beyond that internalization is to give them an undue weight. And so she makes a choice, and the outcome of that choice is…well to answer that choice, I not only have to start asking questions about physics and reality and what would actually happen to a woman walking across the ice hauling a sled, but I would have to care, and I find myself asking, do I care? She’s a fiction. But the choice she’s makes, that isn’t a fiction for me.

And for Ilan, I tend to read that ending as pretty final. Though I had one reader who re-ordered the book and his re-ordering doesn’t make things that much happier, but he imagines that last section as the first section, chronologically. And so Ilan actually does get together with the woman he meets while he’s wearing a bomb, and they almost break up but don’t, and they go on a climbing trip and she dies. The reader had good logic, and I’m willing to accept that reading. But for me the three versions are mutually exclusive but also dependent upon each another, and in the third version, the tension Ilan feels between the absence of romantic love and the absence of God finally comes together for him to see, and he chants, “the Lord is God, the Lord is one.”

For me what’s happened with him in that doubling is that the lyric leap has happened, he’s crossed the gap between the two parts of the metaphor, and on the far end of that second part he is finally in that space that’s unitary and monolithic and he can act, and he knows what he must do as that action. Of course, that action has the advantage of getting him out of having to make any future choices, or be plagued by second guessing in twenty minutes. In Sarah/Sara the lyric leap opens, which allows her to make choices, and in his case the lyric leap closes.

So for me, the closing of that leap, the allowing him to put all these things together, was when I began to read the crushing decimation implied in the word [dakka] in the third line of Psalm 90 with the “pressed cakes and braced support” implied with [ashishot] in the second book of the Song of Solomon, and so that the ecstatic absence of a romantic lover and the ecstatic romance with an absent God become one and the same, and they all are resolved through compression, through decimation. And I think, you know, in that sort of development of the thematic arc, what my third book is eventually exploring is what it might mean to accept dependency on an indeterminacy, to love constantly in the gray zone between the two conflicting offers of meaning.

“Two conflicting offers of meaning?” Can you say just a little bit more on that?

[Laughter.] Sure. In the case of Ilan, those two offers might look like to either radically choose the side of a kind of aetheist will to power and acceptance, or to choose a radical ordering of the universe by a God who authorizes violence. For Sarah that might be something closer to the choice between “I will define myself as a victim, but that’s no good; or, I’ll define myself as an executioner, potentially of my parents, but that’s also no good.” Those are kind of two offers and she’s able to leave them while Ilan conflates them. So if the first book is a question of, “What does it mean to choose to live, whether one succeeds or not?” Then the second book might be: “What does it mean to choose to die and kill a lot of people?” Which arrives out of the same crisis. “What would it mean to accept (in the case of this character) that one needs the Holocaust to still exist?” That that is the authorizing principal and that’s what you’re going to do—you’re just going to live with that. That comes with a kind of complicity, you know?

I hope I’m not speaking too much out of school, but my friend Shlomi Lavie, who did the album that went along with A Song of Ilan—we did these performances in different cities and we drove around a lot together and we did a lot of good road trip time talking—he was saying how his grandparents met because they had both lost their spouses and children before then in the Holocaust. And so he’s like, “I’m kind of glad, because without the Holocaust I never would’ve be born.” [Laughter.] And of course he’s not saying that he’s glad that there was a holocaust, right? But he’s grappling with that notion of…without it, where are we? I think that kind of question is the one that I’m toying with in the third book.

I hope I’m not speaking too much out of school, but my friend Shlomi Lavie, who did the album that went along with A Song of Ilan—we did these performances in different cities and we drove around a lot together and we did a lot of good road trip time talking—he was saying how his grandparents met because they had both lost their spouses and children before then in the Holocaust. And so he’s like, “I’m kind of glad, because without the Holocaust I never would’ve be born.” [Laughter.] And of course he’s not saying that he’s glad that there was a holocaust, right? But he’s grappling with that notion of…without it, where are we? I think that kind of question is the one that I’m toying with in the third book.

I like very much what you said a moment ago, that the three parts of A Song of Ilan are “mutually exclusive but also dependent upon each another.” I do think that that’s absolutely right, and what I found so interesting about the book. Without those preceding two sections, the third section of the book can’t work; its depth, what the reader brings in—these alternatives—that’s where the gravity comes from. I like very much that separateness.

Though I will say—not to be the one talking too much—that I am interested in this other reader’s interpretation of reading the book backwards, so to speak, of reading the final part as the first, in terms of the “tale” of the book, regardless of its telling. And I do think the text might offer that opportunity. I think you could argue that it provides alternative narratives.

What I love about that possibility—and you know this is one of my favorite things in the world—is the way it might gesture toward the multiplicity of time and space, that all these things do get to co-exist in the same way that Sarah’s future journal co-exists with her present action. Technically it’s an envisioned future, perhaps, but emotionally it doesn’t seem to matter—because emotionally it “happens,” in some sense, regardless of when. That simultaneity adds such a richness to the book, by asking us to consider those things at once and hold them in place—both existing and not existing at the same time.

Perhaps this is why I’m drawn to this alternative reading of A Song of Ilan. Or, rather, I’m drawn to both interpretations existing simultaneously.

Yeah. And I’m open to multiple readings of the book. I like the idea of there being multiple ways of determing…if we were to assemble these things. You sent me that Rivka Galchen article from the New Yorker about the multidimensionality necessary to have a quantum computer and to have a q-bit that would be both “yes” and “no” at the same time, right?

Yes, exactly.

It gets to occupy both spaces at once and have this great processing power. On the purely fundamental level, I think that’s what poetics—if they’re working—have to offer, that opportunity to hold paradox and to hold it outside of language, to gain a different kind of processing power that may or may not come back out of its entanglement and conflate into a determinable statement, but certainly can come back out of that and conflate into a feeling and knowledge and understanding and action. And now we’re moving well outside what narrative is or does, but I think of all the recent research that shows us that our notion of conscious decision-making is a post hoc rationalization of something that’s happening in the non-verbal portion of our brain, which is way more powerful than our conscious portion, or how limited our ability to be congnitive is. I always go back to that Radio Lab episode in which they talk about the people who had to memorize seven numbers, and how in walking between two rooms when they’re interrupted by someone who asks them if they want an apple or a piece of cake, they will always choose the cake. While people who only have to memorize four numbers have enough processing power left to say, “Cake is bad.” [Laughter.] Three digit spaces is all the difference between healthy living and not.

So contending with thinking between things, with accepting indeterminacy, I think that’s what I…I think we commune over that often in what interests us in literature.