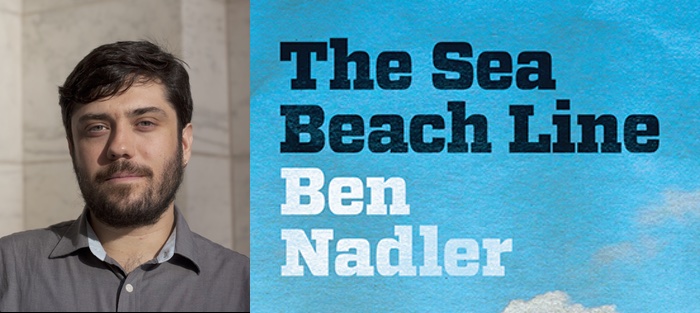

Ben Nadler and I first met as seventeen-year-old writing students at the Pennsylvania Governor’s School for the Arts, a now-defunct state-funded summer program. In our first days there, we connected in the ways that teenagers do—over band shirts and backpack patches, the youthful signs and signals of a common mind. It was the beginning of a conversation that has continued for the past fifteen years: together we’ve gotten tattoos, danced in mosh pits, argued about comparative religion and Midwestern culture and Salman Rushdie, taken Greyhound buses to Pittsburgh, leased Brooklyn apartments, been detained by police. Ben introduced me to the love of my life—the City of New York, where we’ve both lived for many years.

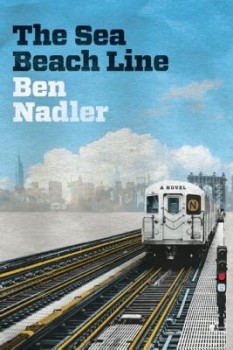

For me, reading his new novel, The Sea Beach Line (Fig Tree Books), was like talking with him for hours on end—and if you ever have the opportunity to talk with Ben, you’ll discover what a privilege those conversations are. His thoughts are erudite, original, nuanced, and humane, bridging the gaps between disparate philosophies and transforming them. Always, I come away with a different view on things—and a few new books to read.

We convened last week to talk about his book and, as usual, I learned a great deal. Our conversation, given below, touches on Lou Reed, Hasidic tales, anarcho punk, and the dangers of glamorizing trauma.

Interview:

Catherine Tung: One of the great things about The Sea Beach Line is the way that other texts and other books are woven throughout the novel. The protagonist, Izzy, is a reader and a bookseller, and so books are a big part of the way he sees the world. Are his favorite books similar to your own tastes and inspirations?

Ben Nadler: I do have a deep interest in Hasidic and Yiddish literature, which is a lot of what Izzy reads. For me, his comes from my paternal grandparents, and from stuff I’ve studied academically, but also from the fact that when I was a bookseller, we got a lot of collections from the apartments of old Manhattan Jews who had died. So there was a strong feeling of these books, this tradition, physically passing through my hands. But because Izzy is in many ways modeled as a “yeshiva bocher,” a young (and maybe naive) student, from this literature, I immersed him a bit more in Jewish religious and mystical literature than I have been in my life.

Most of the early signposts in the novel, Rebbe Nachman, Kafka, Valis by Philip K. Dick, are definitely very important to me. But no, I don’t have the same obsessive, unstructured interest in Jewish religious texts that Izzy does. I actually had to do quite a bit of research to keep up with him on that stuff.

Some of my personal reading interests worked their way into the book through other characters, like Alojzy’s interest in crime fiction, or Mendy’s references to anarchist texts. I know it’s natural to associate the writer with a first-person narrator—and knowing me so well you probably see some connections others don’t, maybe even that I don’t—but I felt parts of myself scattered through a lot of the other characters.

Also, keep in mind that a lot of the books referenced in The Sea Beach Line don’t exist. Curating, butchering, and when necessary creating the literature was a big part of writing the book.

What’s your favorite book that you created for the novel?

What’s your favorite book that you created for the novel?

The Yeshiva Bocher is the most in-depth, and the one that most self-consciously builds on Hasidic narrative tropes and traditions. But I like Caravan of Cats, which is more fantastical, and genuinely weird.

I like that one too!

Your first book was about a punk rocker who joins the military, and punk culture continues to be present in your more recent work, albeit more obliquely. How did punk influence you when you were first starting to write?

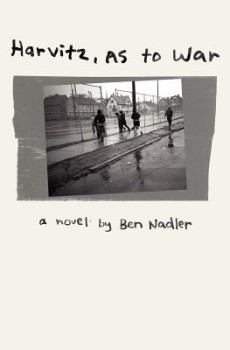

My entire worldview is informed by Punk Rock. That’s what gave me the confidence that, not only did I have right to write, but that I had a right to be alive, to exist as myself. This sentiment is definitely a part of my first novel, Harvitz, As to War (Iron Diesel Press). More recently, my monograph, Punk in NYC’s Lower East 1981-1991–which is part of Microcosm’s Scene History series—was sort of a love letter / thank you letter to anarcho-punk.

Anarcho-Punk was like putting on the secret x-ray glasses. It gave me this beautiful critical lens that let me see all institutions and traditions as challengeable.

I started writing with zines. Spoken word was a factor a little later (this was the late ‘90s, after all) but punk zines first. I got into Governor’s School—where I met you, and other writers like Rosalie Knecht—based solely on poems I wrote for a photocopied zine. And then I got into the New School, I believe, primarily by stuffing the poetry chapbook I made at Governor’s School into the envelope with the application.

But it’s not just that Punk got me writing in zines, when I wasn’t engaged enough in school to learn about writing or literature there. Punk taught me I should do something productive, rather than just taking pills, or watching TV, or sitting alone in the dark. That being said, I think about things like Punk the way an (Orthodox) friend spoke to me about religion: These things are soap. When you are covered in dirt and muck, you need that soap. But then you have to remember to rinse the soap off with water.

You completed an MFA at City College of New York. What are your feelings about MFAs, specifically those located in New York, especially when an MFA/NYC dichotomy has recently been drawn?

Years before I got an MFA, I read an interview with Phil Levine, who as I recall basically said that MFAs will save you time. You won’t do work you wouldn’t be able to do otherwise, but you’ll be able to it earlier, and more quickly. That’s part of why I went to an MFA. I had already written a book, I was reading through Dickens and Dostoyevsky while working shift jobs, and I felt I was progressing as a writer at some rate. But I’d already wasted so much time—with the drinking, and everything else—that I felt I couldn’t waste any more.

I’m glad I went to City College. I got to study with some great professors, like Peter Trachtenberg, Salar Abdoh, and Keith Gandal, and I got to be in class with some very talented writers, like Andrew Worthington, Tracy O’Neil, and Joe Okonkwo. I have certainly been privileged to have access to the literary community and publishing industry of New York City. I sold my novel without an agent (though I don’t know I’d try that again), which might not have been possible if I wasn’t here to meet the publisher in person.

I don’t love living in New York, in many ways. I like being in the woods, up in the hills, that kind of thing. But look: five generations of my father’s family have lived in New York City for at least part of their life, and generally hated it. But what, life is to be enjoyed? My great-great-grandfather died in a park in the Bronx, reading a newspaper out loud to his friends while wearing his thick black coat and hat (he was an Orthodox Jew, from Vilnius) in the hot sun. This is a fate I understand.

In many ways, The Sea Beach Line draws from your own experiences as a bookseller. Had you known for a while that you wanted to write about these experiences? Had you ever considered writing about bookselling in a nonfiction mode, or did you always have a novel in mind?

In many ways, The Sea Beach Line draws from your own experiences as a bookseller. Had you known for a while that you wanted to write about these experiences? Had you ever considered writing about bookselling in a nonfiction mode, or did you always have a novel in mind?

I always wanted to write fiction about bookselling. Even when I was selling books as a nineteen-year-old, I was more interested in the mythic quality of it than what was actually happening day to day. At the time, I tried to write a story about a bookseller who dies in the snow and is then reincarnated. It was a terrible, terrible story. But I was still just beginning to learn how to write fiction.

I wrote a few poems about bookselling, about pushing our carts in the street, things I worked on in a notebook while on the street. None of it was very good, but I guess it got things rolling. Slow build.

There are some good memoiristic nonfiction pieces out there about bookselling, though: Corey Eastwood wrote a great piece in the Brooklyn Rail a few years ago, and Aaron Cometbus has written about it in some of his zines.

One of the characters, Rayna, the Hasidic woman who’s run away from home, often tells stories in her conversations with Izzy, and you’ve mentioned that some of these stories are recastings of Hasidic tales. Can you say a bit about what Hasidic tales are—their origins and purpose, and how they’ve appeared in literature over time?

Well, Hasidism is very codified now, but when it started, it was an ecstatic, popular connection to religion. People in shtetls in Poland and Ukraine who spoke Yiddish, and who didn’t necessarily have the education or access to rigorous study of Hebrew and Aramaic texts that scholars in urban centers like Vilnius did, were suddenly connecting to religious and mystical ideas. So this genre of Hasidic tale was basically a way for rabbis to use oral folklore to connect these people to these ideas.

No two things in history are the same, but since you and I have shared connections to Protestantism, and Protestant music specifically, I would definitely draw a parallel to Hasidism and the Protestant Reformation. You know, this idea that you no longer needed that complex (albeit beautiful) cathedral music. Hasidic tales are like those four-part hymns anyone can sing. Or that any preacher can write new lyrics to.

There is influence from many Hasidic tales in my book. I talk about Rebbe Nachman (who was the great-grandson of the Baal Shem Tov, who founded Hasidism) on the first page, and reference him constantly throughout the novel.

I personally came to this tradition through literature. Through I.B. Singer, who grew up in the Hasidic world, and through Kafka, who grew up in an assimilated world, but learned about the Hasidic narrative tradition from people like Jiří Langer.

But there is also a much older Jewish narrative tradition of Aggadah/Midrash. Basically, rabbis had a lot of different tools to try to interpret Torah, and one of them was to actually compose tales about biblical figures, to fill in the gaps and explain things. While my motives are different than those rabbis’, I always found this tradition very exciting, since I was a kid and encountered some of this stuff on my father’s bookshelf in the volumes of Ginzberg’s Legends of the Jews. This was a revelation, that it was not necessarily sacrilegious to rip apart a text, collage it into something new, to form or express a different meaning. So you see that tradition a lot in the book, like when Rayna finds her way into the Book of Esther, or with the whole Binding of Isaac section.

When you put it that way, that process kind of sounds like a zine.

When you put it that way, that process kind of sounds like a zine.

Yeah, there are connections there. Take d.a. levy, who did a lot of stuff with collage and underground publishing in the ’60s which influenced later punk zines. He was looking for his way into different spiritual traditions, both Buddhism and Judaism. He was on the outside, trying to access these things through assemblage and mimeograph. In one poem he wrote: “i am a levy of the levites & last week a rabbi thought i was kidding when i told him i was interested in judaism.”

Another early link that was important to me was Allen Ginberg’s Kaddish. He took this central prayer, the Mourner’s Kaddish, and he made it a new poem that is unique and personal, but still so valid and important. That has always been instructional to me.

The precipitating incident of this novel is the disappearance of Izzy’s wayward father. As Izzy goes searching for him, he essentially takes on his father’s life—his job, his associates, his possessions. What do you feel are the literal and symbolic implications of this transformation?

Well, there are certainly literal implications—or better yet, consequences—for Izzy. That’s a big theme in the book, that actions have consequences, you always got to pay.

I’m hesitant to try to define “symbolic implications” in my writing. That’s more for a reader to decide. But I think that gender roles are a pretty central theme in the novel. What should a man do? How should a man act? What are our models for masculinity? How does ethnicity and class inform these models? These are big questions.

For me, Izzy’s transformation seemed to literalize the fear—and sometimes desire—that we all have about turning into our parents.

I think for Izzy the desire is maybe bigger than the fear, but yes, absolutely, I see that.

Jewish history and texts figure heavily in this novel, and in Izzy’s character. What does Judaism mean to Izzy? Is it too simple to equate it with his father? Is belief necessary to engage with religion, or to write about it?

I made Izzy Jewish—instead of half Jewish like me, or like Sammy Harvitz in my first book, though I love American hybridity—because this book is so much about Judaism—or Judaisms—and I wanted to fully immerse him in questions of Judaism. There are lots of different ways to be Jewish in the book, offered by Izzy’s father, Alojzy, yes, but also by his mother, his stepfather, his sister, Mendy, Rayna, Rayna’s father, pretty much everybody.

You’ve seen me barefoot. I have “FAITH” tattooed on one foot and “DOUBT” on the other. Never know which way to step. But yes, I think you need some measure of belief or faith to write about religion. To be fair though, I think you need some measure of faith to write about people, too.

As I’m thinking about this, the Lou Reed song “Busload of Faith” is playing in my head. “You need a busload of faith to get by.”

Of course, when you are talking about types of Orthodox Judaism, or other heavily structured religious systems, there’s a distinction between belief in particular law or dogma, versus a more general faith.

So for me, do I believe in following all the laws of Kashruth? No. On the other hand, do I believe, however, that my actions have consequences, that I’m part of a connected world, and that every bite I take into my body has an effect on me and on the world? Yeah, absolutely.

What about you? You come from a Christian background, personally and artistically. Is that rooted in faith?

I’m sure it is, in some way. When held up to any scrutiny, Christianity’s worldview is almost impossible to reconcile with reality, and yet it’s so beautiful as art and as narrative—there’s a lot of emotional realism in Christianity for me. Religions do present an incomplete view of the world, but the secular view is incomplete as well. You really need both.

Without giving too much away, a lot of this novel focuses on the effects of trauma, of life as trauma. Do you see The Sea Beach Line as a pessimistic novel? Or is there beauty in that trauma?

It’s a sad novel, I think. It’s definitely a book about trauma.

I hope that some people could find beauty in the book, but no, I don’t know that I could responsibly talk about trauma as beautiful.

I never thought glamorizing trauma or pain was a good idea. Punk rock songs that make heroin seem cool are terrible. But like the older brother says in the Baldwin story “Sonny’s Blues”: “But there’s no way not to suffer—is there, Sonny?”

A book which had a huge impact on me in college is Moments of Reprieve by Primo Levi. It’s a short book, maybe just a pendant to his more known Holocaust memoirs, but he talks about the rare moments of beauty, faith, or human connection that he experienced in Auschwitz.

The Sea Beach Line blends the conventions of several different genres—literary fiction, thrillers, heists, the aforementioned Hasidic tales. Do you find genre categories useful as a writer? Do they provide conventions to push against?

I don’t know if find these things useful as “categories” (that’s maybe more the publishers and publicists), but I certainly find them useful as structures. For example, I’m not a formalist, but I learned a lot about poetry, about lineation and rhythm and sound, by forcing myself to write a lot of blank verse, things like that.

So while my novel isn’t strictly a thriller, setting up a mystery, something with a clear question and clear clues, forced me to work within this structure. Which made the book stronger. I ended up dividing the novel (which is fairly long) into the three constituent “books” so that I could structure each part individually, in addition to the overarching structure.

But absolutely, working within a structure is all about pushing against it, seeing what it can do and how much it can bear. Studying the traditions, and seeing where these forms have succeeded, and where they’ve failed. Faith and doubt.