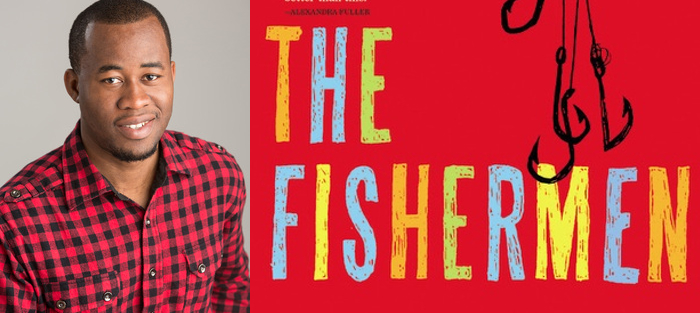

Chigozie’s Obioma’s first novel, The Fishermen (Little, Brown and Company), was written in the spirit of exile—from family, from country—and out of the experience of the Igbo people in Nigeria. Its images of blood, water, and madness run with a deep and mythic weight that is supple enough to contain both local and historical context. Such flexibility gives intellectual weight and lastingness to the book. Obioma’s characters lose control. Their experience does not equip them for the things that happen in their lives. They are determined to act, to change their circumstances, but go headlong into disaster, and their struggles to regain control give the book real depth. We feel something when we read it.

Shortlisted for the Booker in 2015, the paperback of The Fishermen appeared this summer.

Interview:

Blair Austin: What led you to become a writer?

Chigozie Obioma: When I was about eight or nine, I was always down with malaria or something, and frequently spent several days in the hospital. During those days, my dad would sit by my bedside and tell me stories. Then one day, healthy and at home, I asked him to tell me a story, and he said, “Go and read it yourself.” He gave me a book and when I went and read it I discovered that one of the most fascinating stories he’d ever told me was in the book! That book was Amos Tutuola’s mythic odyssey, The Palm-Wine Drinkard, which also happens to be the first black African novel in the English language. That was a pivotal moment. Prior to that I had always seen my dad as this great man who had this vast reserve of stories, but then I saw I could actually get this thing from books, and I started reading voraciously. Then I began to replicate the stories in written form, so that was the point where I moved from a storyteller to a writer.

Any other early literary influences?

That list is extremely exhaustive but most prominent amongst them are Amos Tutuola, Thomas Hardy, Chinua Achebe, William Shakespeare, Euripides, Homer, Sophocles, D.O Fagunwa, Wole Soyinka, and John Bunyan.

Tutuola and Bunyan have a great deal in common, even if their maps are different. What is it about each of them that inspires you?

I think that in the deep of my mind, I make a distinction between their aesthetics, but in my writerly sense, they are indistinct. There, with Tutuola, that rawness, that earthiness that I must associate with the now slightly buried civilization of the West African. And the time in which Bunyan wrote, in which Christianity was at the center—if not the spine of Western civilization— feels similar, for we know now that there has been a radical change, a people retracing their steps, sweeping clean the footprints so that the past cannot be returned to even if future generations desire to. I think this is the affinity that both works share.

I think that in the deep of my mind, I make a distinction between their aesthetics, but in my writerly sense, they are indistinct. There, with Tutuola, that rawness, that earthiness that I must associate with the now slightly buried civilization of the West African. And the time in which Bunyan wrote, in which Christianity was at the center—if not the spine of Western civilization— feels similar, for we know now that there has been a radical change, a people retracing their steps, sweeping clean the footprints so that the past cannot be returned to even if future generations desire to. I think this is the affinity that both works share.

What was the seed or germ for The Fishermen?

The germ of the idea came from a very personal place and the emotion of being homesick. I left Nigeria and was living in a very interesting place, both paths long and unknown to me, in Cyprus. While there, I began to miss my brothers especially, and sisters; growing up in an African family, I shared a lot with my brothers and was closer to them. During a phone conversation with my dad one evening while I was in Cyprus, he told me of the growing closeness between my two oldest brothers, who while growing up had a very serious rivalry between them. I started to think about that closeness and what it means to love your brother, and also what if this time never came, what if they never came to understand this love of brother and closeness of family. That reflection brought the idea of a close-knit family that is destroyed.

Also, I had been reading Will Durant’s The Great Civilizations, and something he said again and again stood out to me; he said, “a great civilization cannot be destroyed from the outside; it has to come from within.” I was thinking of what could come from the outside and destroy a family—that is where the germ of the idea came from.

What were early challenges or stumbling blocks as you began to write the book?

The very first “challenge” was the story itself, my worries about whether or not it would make sense to readers. I wrote the story of the novel one night, a few days after the germ of the idea was first planted in my mind. I had about twelve pages of foolscap paper filled in one sitting. I knew it was a novel from the start, but just wasn’t sure how to tell it. But I wanted to do something unique—to contribute to the possibilities of what we can do with fiction as an art form. I was about sixty-thousand words deep into the novel when I began to worry about how it would be received. So I decided to test the waters. I stripped the novel down to the essentials of the plot and sent it out to small journals as a short story. I abandoned the novel while waiting for journals to accept the story, and in the interim, within which I got a few acceptances, I wrote another novel from beginning to end. After receiving a few acceptances, I sent it out to big journals: Paris Review, The New Yorker, Virginia Quarterly Review, etc. It was not until 2011 when VQR sent an acceptance that I picked up The Fisherman again, and I completed it around August of that year.

I revised [the manuscript] some eighteen or nineteen times before letting readers read it, and then an agent, and then an editor who would put me through two more stages of revisions. It was an arduous but satisfying process. And I have come to the valiant belief that writing actually happens during revision.

To what extent does the project of the novel need to remain mysterious to you? Sometimes in the rewrite it’s difficult to work through the overfamiliarity one feels, and the inevitable narrowing, and deepening, of the project. Do you experience this?

To what extent does the project of the novel need to remain mysterious to you? Sometimes in the rewrite it’s difficult to work through the overfamiliarity one feels, and the inevitable narrowing, and deepening, of the project. Do you experience this?

I think that writing is, to a great extent, decision-making. But I will say more like radical decision making. All your senses need to be at work here, carrying you through it. We were at Michigan together and you knew how I reacted against what I thought was too much socializing, because I think it took away from the time needed to pour into the work. If you immerse yourself in something, you are committing to it—and a relationship happens. Everyday, you discover something new about it that you didn’t know was there. To me, the “overfamiliarity” never occurs because I am constantly getting distracted by new discovery. Today, I discover the creature likes purple things and while I am still trying to figure that out, I discover that long ago, it played softball. This continues until the work is done. Perhaps I encounter overfamiliarity during revision, but that is usually a sign that I should cease and desist.

This book beautifully explores language through many devices: lyric, proverb, poetry, and code switching. How did you negotiate writing in different languages?

What I often elect to paint in my fiction is a portrait of what I should call West African realism. It is the way we live, as opposed to the way we ought to live. The difference is that the former captures the nuances of the West African grappling with western civilization, which it has adopted, but molding it into a hybridization of his own traditional culture, while the latter portrays the nuances of the West African living out the practicality of Western civilization.

One good thing we got from the British is the English language. It is a beautiful synthetic language that is malleable; you can do anything with it. It has untrammeled possibility. Regarding code-switching, I played with the languages because it has big political implications. I wanted to be able to capture as much as I could the body politic of Nigeria. That would encompass the multi-various languages. Nigerians by default are almost always multilingual from birth, or at least bilingual. I grew up in the West, which speaks Yoruba. But my parents speak Igbo. In the book, the family speaks three languages. The best way to navigate through this territory, the best way I could show this is that each character is associated with one primary language. The Father, a lover of Western culture, is always speaking in formal English. The Mother, being more traditional, always speaks Igbo. The Children, being playmates with other local kids, speak Yoruba. So English, when used, creates craters between family and friends. When people switch to this language, they intentionally create distance. When the Mother or Father is angry, he or she switches to English. Pidgin English is used by the uneducated; it is the “official language” of the masses. It is very specific and yet all the traits of the major languages of the area are in it.

You’re writing in the Real and there are rich elements of the Allegorical, as well. How do you balance the two?

I follow the ethics of the Igbo imagination in my writing, and it has also shaped my aesthetics. In the Igbo thought, there is no difference between the world of the physical and the supernatural. In many ways, it is how I see the world. Benjamin submits in The Fishermen that whatever happens in the ordinary must have first occurred in the spiritual. I believe that is true, and I try in my fiction to make present to the reader this truth.

Yet in terms of nuts and bolts, what appeals to you about realism? Do you see it as one of many tools near-to-hand?

I think, and this is a big I think, that a story about human beings cannot fully work outside of the realm of realism. There has to be some measure of the believable, of the real in it. In my opinion, some of the sci-fi stuff fails for me because the writer is trying to create something completely out of the realm of possibility. And because no one else but he would have the full knowledge about that world, the readers have to rely fully on him to provide all the parameters to understanding that world. That is not always possible. So, as much as some writers want to sound edgy by contending with the age old adage to write what one knows, it is true. So, I believe that a little piece of the supernatural, of the metaphysical, and of the unknown placed within the realm of the known is how—at least to the West African mind—the world works.

Do you always write in English?

Yes. English is the language of western education, with which the idea of the novel came. The novel is Western; it is not African. While storytelling may be universal. Yet, the English that I write is mine, since my ancestors were made to adopt it, two generations before me.

Are there any differences that you find in the “American Novel” as a form or construct?

I think, on the whole, American Literature may be facing a decline, at least in comparison with what was produced in the recent past by writers like Roth, McCarthy, Morrison, and Bellow, amongst others. There seems to be an over-socialization among writers, resulting in what I think is a trivialization of Literature as an intellectual and high form of art. It might seem like beating a dead dog, but the social media has contributed immensely, and so has the social atmosphere of the now. I wrote about one aspect of this “decline” in an essay for The Millions published last year called “The Audacity of Prose.”

Where is your fiction writing taking you next? How do you grapple with the pressure of expectation for the “next one?”

Before The Fishermen was published, I had started to think very deeply about the novel I have just completed. I had even written a short story out of it, while still in graduate school. So, the vision will not change despite the kind of attention the first book has received. This essential negates the pressure you talk about. That said, I do, of course, have anxiety as I did of the first novel, whether or not it will make sense to readers.