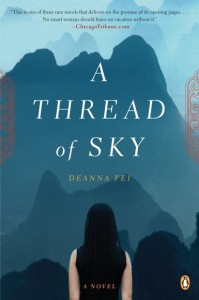

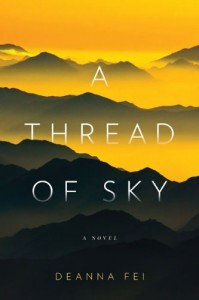

I discovered Deanna Fei’s A Thread of Sky (Penguin) last year, in the middle of a giant funk. It was late April; blue-skied, short-sleeved spring had just begun, but all I could think about were endings. My MFA program was over, and with it my break from the working world (or at least, from the working world in which one has to wear nice pants). My cohort—the ready-made social group of the last couple of years—was disbanding. My desire to write had evaporated, too. I put my thesis manuscript away, because just spotting it out of the corner of my eye induced in me the same allergic reaction I have to stumbling upon reruns of Friends: a mix of familiarity and discomfort. In short, I was scared. It’s easy to feel like a writer when you’re in a graduate writing program. But in April, stripped of the pressures—really, reassurances—of deadlines and workshops, I felt like a pretender, a loser with a laptop.

I discovered Deanna Fei’s A Thread of Sky (Penguin) last year, in the middle of a giant funk. It was late April; blue-skied, short-sleeved spring had just begun, but all I could think about were endings. My MFA program was over, and with it my break from the working world (or at least, from the working world in which one has to wear nice pants). My cohort—the ready-made social group of the last couple of years—was disbanding. My desire to write had evaporated, too. I put my thesis manuscript away, because just spotting it out of the corner of my eye induced in me the same allergic reaction I have to stumbling upon reruns of Friends: a mix of familiarity and discomfort. In short, I was scared. It’s easy to feel like a writer when you’re in a graduate writing program. But in April, stripped of the pressures—really, reassurances—of deadlines and workshops, I felt like a pretender, a loser with a laptop.

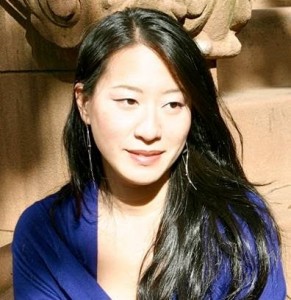

And speaking of that laptop—I spent a lot of time on it during this funk. It’s amazing how much web-surfing can look and even feel like writing—fingers on the keyboard! typing!—if one’s denial is deep enough. It was during one of these Internet binges that I made my way to the book section of the New York Times, where a debut novelist named Deanna Fei was being reviewed. Her name rang a bell. I typed it into Facebook, only to discover that we had a couple of friends in common—we’d gone to the same college, graduating a few years apart. I checked out Deanna’s author page, which led me to her blog. The first entry I read revisited some quotes on writing—from Sylvia Plath, D.H. Lawrence, and others—that Deanna had compiled in college, when her dream was to “be a writer.” She reflected:

Some of these statements don’t seem quite as profound to me now as they might have back then, and if I redid this exercise today, I’d probably revise the list substantially. But every one of them still speaks to me, very clearly, in at least one way: They’re about writing. Not about “being a writer,” but about writing. And—it’s not always easy to remember—writing is what it’s all about. Nothing else.

I’d been told this before, but I needed to hear it again just then. It helped. I went out and bought Deanna’s novel, A Thread of Sky, and was reminded further of all the wonderful things you can do with words if you let yourself get them down on paper, and give yourself time to rework them and test them against your meaning. There is a moment in A Thread of Sky—the story of six women, family members, who take a package tour of China—in which one of the characters finally confronts her grief over her dead husband, by way of a very mundane act. I’ll resist saying anything more about it; I don’t want to rob other readers of the experience of having their breath taken away by the deep sadness and utter simplicity of the moment. The same passage that knocked the wind out of me also knocked some sense into me. This is what writing is about, I remember thinking: illuminating emotional truths, exploring interesting questions about people and the world—above all, forging a connection with your reader. This is the work that makes those anxieties about “being a writer,” however inevitable, seem beside the point. Nobody ever moved anybody by being a writer. Only by putting words on the page that ring true.

Originally from Queens, New York, Deanna attended the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and received a Fulbright grant to research A Thread of Sky in China. In the Huffington Post, The Millions, and other venues, she’s written with insight and humor on the writing life, literature, identity, family, and reality TV. She shared her thoughts with me on these and other subjects over email in February.

INTERVIEW

Kate Levin: This may be a strange place to begin, but I was overjoyed to learn recently that you sometimes dive into celebrity gossip sites while warming up to write. As someone with a bad UsWeekly.com habit (the need to know what Lindsay Lohan’s up to always seems to strike just as I’m sitting down to work), I wanted to ask if you’d share some of your favorite pre-writing gossip sites?

Deanna Fei: I don’t think any of these sites need my endorsement, but my usual stops are HuffPost, TMZ, and E!. I like a mix of narrative, eye candy, and plain tawdriness.

You noted in an earlier interview that celebrity gossip sites are rich in stories. You make a similar observation in a piece for the Huffington Post, “Why Every Writer Should Watch Jersey Shore.” Thanks to blogs and Facebook and the million reality shows on TV, it seems like a story-hungry mind has more windows than ever into the lives of other people. It seems, too, that all of these narratives, all this information, could really impinge on the mental quiet needed to write. How do you cultivate the concentration it takes to work on a novel?

It’s true that I honestly believe my gossip habit serves as a little warm-up for writing, a way to step out of my own life and into the lives of others. But you’re right: writing doesn’t happen without that final phase, the whiting-out of everything but the one story before you. And sometimes that takes a lot of tricks. I have two laptops—one that’s so old that it crashes if I do more than word processing and maybe looking up a few references on Wikipedia, and one that I use for everything else. When it’s time to write, I put my other laptop in another room and close the door. I turn my phone to silent mode and put on noise-canceling headphones. And I don’t let anyone interrupt me. Maybe it seems self-indulgent, but writing is creating a whole universe for your characters and your readers, and you have to protect the process.

The idea for A Thread of Sky grew out of a package tour of mainland China that you took with your own sisters, mom, aunt, and grandmother. In your acknowledgments, you write: “…while this book was, in part, inspired by them, it is not about them; it does not depict their histories or their personalities. I offer them my apologies for potential misunderstandings, and my lifelong admiration.” Did it complicate things that the story was rooted in a recognizably real family experience? Or did it feel like the work of creating any fictional characters?

Fei reads at B&N in Park Slope, April 2010 / credit: from author's website

There was a part of me that deeply regretted the fact that my story had a recognizably autobiographical basis, because I couldn’t help worrying about the assumptions readers might make about my family and the ways that my family might feel exposed. In terms of my writing process, the main complication was always making sure that nothing remained in the novel simply because it had happened in real life—one of the worst justifications to write anything.

But in general, I think that whatever the inspiration for fictional characters, the challenge of making them spring to life is much the same. And the truth is that people will assume autobiographical elements in your writing no matter what, especially with a first novel. You can’t let that stop you. You simply have to write what moves you.

You went to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and worked on A Thread of Sky while you were there. I imagine it’s very different to put up portions of an embryonic novel for critique than complete short story drafts. What was it like trying to draft a novel while simultaneously receiving feedback from other writers?

For me, one of the hardest parts of writing my first novel was getting up the nerve to start. So that novel workshop was most crucial in making the stakes seem manageable. I could tell myself I was simply drafting sixty pages so that I could get into this class with Elizabeth McCracken, as opposed to starting my first novel.

In terms of the actual workshops, it’s true that my novel was too embryonic back then for the feedback to be very useful in itself, especially when we were so accustomed to thinking of plot and structure and language on the granular scale of the short story. But the encouragement and sense of fellowship were invaluable. So was simply witnessing how the process was terrifying and bewildering for everyone, whether it was their first novel or their third.

Since I left the workshop, I’ve mostly reverted to working in isolation for long periods of time, and recognizing when I need to turn to my trusted readers and editors. But those two years at Iowa were such an intense, immersive experience that hardly a day goes by when I don’t hear some of those voices: Frank Conroy‘s exhortations to inspect every sentence for “meaning, sense, and clarity”; Ethan Canin‘s edict that you write to explore, not explain; Elizabeth McCracken’s passion for research; and on and on.

This is from your thoughtful and funny essay in The Millions, “A Different Species: A Chinese American Writer in China,” about moving to China on a Fulbright to work on your novel:

I moved into a studio apartment in a traditional alley where my neighbors’ vigilance in watching me seemed matched only their vigilance in not speaking to me. The locals I met seemed less interested in getting acquainted than in handing out their business cards—according to which, no one ranked below Managing Director.

One of the things I found so interesting about your essay is that I tend to think of research-for-writing as a way to feel at home in a subject or setting, to “get it”—but it seems like the alienation that you felt in China was really productive for your work. I was wondering if you could talk about that a bit.

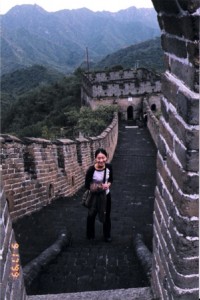

The Great Wall / credit: from the author's website

You raise a really interesting question. To me, it’s both: you need to feel at home with your subject, but you also want to let it retain a sense of mystery, a smidgen of unknowability. I think it’s crucial to immerse yourself in the world of your characters through research, imagination, and/or literally moving to the place where their story takes place, as I did. But a writer is most crucially an observer, someone who stands just a little bit apart. You never want to feel too comfortable; you need a little distance to see clearly.

More broadly, the feeling that you have to “get it” completely can be deadening in fiction—and, I think, can even verge on hubris. In the same way that a traveler eventually has to look past that urge to fully digest a foreign country, a writer has to embrace the fact that your subject will always remain just slightly beyond your grasp, in the same way that your characters will never behave exactly how you anticipated and your novel will never be exactly what you set out to write. To me, that’s proof that you’re really writing, when the story is a living thing.

Now, to dig into the novel itself: the point of view rotates by chapter among the six women in the book—three sisters, born and raised in NYC; their mother and aunt, who emigrated from Taiwan to the US as students; and their grandmother, a former Chinese revolutionary now living in LA. The setting shifts, too, as we travel along the “must-sees” offered up by the package tour. How did you know which of your characters’ eyes to lend the reader at any given spot along the tour?

It’s a funny thing: I just knew. I always had a sense of which character had the most at stake in each setting, and that dictated the choice of narrator. Sometimes it was obvious—for example, that the grandmother would narrate the historical capital of Nanjing because the city would evoke her memories of life under the Japanese occupation, as a nationalist activist, as a permanent exile. And sometimes it was more abstract—for instance, that the romantic gardens of Suzhou would force Nora to face the fact of her heartbreak. But there always seemed to be an organic and fundamental relationship between the point of view and the setting.

All of your characters are given equal voice in the novel, but Irene is the only one who has to play the role of both mother and daughter on the tour, and the story begins and ends with her. Do you see her as the heart of the book?

Yes, though I didn’t fully realize that until I was well into the revision. My original intention was to give equal weight to all six women, but I came to see that Irene’s emotional journey was, in many ways, the heart of all of their journeys. She is the center of this family, in bridging the generations between her mother and her daughters and in providing the impetus for this reunion. While the other characters are, each for her own reasons, deeply ambivalent about embarking on this tour, Irene desperately wants to reconnect with her family and her ancestral home. Her hopes, her sense of deep disillusionment, and her eventual coming to terms helped form the overall arc of the novel.

These six women are all faced with very different (often secret) dilemmas, which is part of what gives this tour its crackle of tension. One thing they all seem to be wrestling with, though, is the complicated and ever-changing nature of home—whether it’s an ancestral home, a physical home, or even a person’s own body. Did “home” become a concern for all of your characters because it was a larger concern of the novel, or did it work the opposite way?

The latter—it was a theme that emerged from the characters, which is how I think themes should almost always originate. Otherwise you run the risk of stilting your story for the sake of an idea. It’s funny: the one line that seems to most explicitly contain the heart of the novel—”Jia—family, house, home. In Chinese, it was all one word”—is one that I wrote on my final pass-through of the manuscript.

Your younger characters, Nora, Kay, and Sophie, are especially aware of other people’s ideas of who they’re supposed to be as Asian American women. Their range of responses to stereotyping—variously ignoring it, making fun of it, confronting it through political activism, defining themselves against it, telling someone to fuck off, not telling someone to fuck off—seems to echo a theme of A Thread of Sky about resisting oversimplification and generalization in favor of complexity, multiple ways of being. I was also thinking about this in light of “I Called Amy Tan A Dirty Word—And Then She Friended Me,” your piece about coming up against other people’ assumptions about what your book is. Could you say a little about the struggle for your book to have its own identity, to be read on its own terms?

There were times I struggled with how my novel seemed to be instantly categorized in ways that didn’t ring true to me. Of course, that’s just part of how books get packaged and digested—you know, “If you liked this, try that!”—and there’s nothing wrong with that, per se. But for writers of color, it can be particularly disheartening for the work to be categorized sociologically, which takes something away from our individuality and our art. In my case, I got a lot of Amy Tan comparisons, some of which were complimentary and some of which were dismissive. And in terms of the novel being set in China, there were times that I felt like I’d wandered into a preexisting shouting match between “pro-China” and “anti-China” camps. But there’s only so much that a writer can control. I find that anytime I hear from people who’ve actually read the novel, they always seem to have a highly individual sense of my story and my characters on their own terms, and that’s more important to me than anything else.

Now, to shift topics just a bit—to sex scenes. There are a couple of them in the novel, but I’m thinking mostly of the very climactic (sorry) scene in which one of your characters loses her virginity. Do you have any advice for those of us who have trouble writing sex scenes?

Ah, I love that you ask! I think sex scenes are some of the hardest to write—and they can also be the most essential. They should never be obligatory or gratuitous, of course—but too often, writers just let the moment pass in a line break. That seems like such a wasted opportunity to me. A good sex scene is a good action scene, a high point of tension and conflict, a moment when your characters are (in more ways than one) laid bare. As the writer, just try not to lose your nerve. It’s your duty to see your characters through the moment.

In addition to writing, you teach. What drew you to teaching—and specifically, to the kind of work that you do, teaching in public schools in NYC?

Public education has always been my passion, along with writing. I can’t help wondering why more of us writers—along with journalists, musicians, dancers, artists—don’t seem to connect the problems in our schools with the problem we’re always lamenting: the shrinking audience for our art. When we continue to fail so many of our students, where can we expect the next generation of audiences to come from?

On a more personal level, I find teaching nourishes me as a person and as a writer. I rely on my students to challenge my thinking, and very often, I’m inspired by their toughness and their wisdom. I find schools, and adolescent groups in particular, to be such fascinating microcosms of society. Writing requires a lot of isolation and contemplation, and teaching gets me away from my computer and out of my head; it keeps me from slipping into solipsism. You have to write what moves you, but you also have to write stories that matter.

You do other community-oriented, NYC-focused work in the form of your writing for Open City. Could you tell us about that project?

Open City is an interdisciplinary neighborhood blog and community project coordinated by the Asian American Writers’ Workshop. I’m one of five writers documenting the rapidly changing neighborhoods of Manhattan’s Chinatown, Brooklyn’s Sunset Park, and Flushing, Queens, through essays, photos, interviews, oral histories, poetry, and anything else that inspires us. I was born and raised in Flushing, where my parents still live, and it’s been fascinating to revisit the neighborhood through this new lens.

As we wrap up, is there anything you know now about novel-writing that you wish you’d known when you were working on A Thread of Sky?

There are so many things I wish I’d known. When I was writing my early drafts of A Thread of Sky, I spent way too much time polishing pages and pages that will never see the light of day. I like to think that it was all part of the process, but part of me knows that a lot of it was a waste of time. More importantly, it led me to get too attached to various lines and scenes; it distracted me from the bigger picture. Writing a novel requires momentum. Especially when you’re transitioning from writing short stories, you might feel like you’re sacrificing beauty and precision—but you have to trust that can come later. Also, the force of a novel depends on huge stakes, overarching questions, a sense of expansion—and I think that, in this way, the craft is more akin to film than short stories. I’ve actually gained some of my most treasured lessons about plot and structure from books on screenwriting.

Finally, I know that you’re a fan of Jersey Shore. Any thoughts about Snooki’s forthcoming novel? Should writers of Serious Literary Fiction roll their eyes and grumble about her giant advance, or is it better to take a more generous, big-tent philosophy?

Finally, I know that you’re a fan of Jersey Shore. Any thoughts about Snooki’s forthcoming novel? Should writers of Serious Literary Fiction roll their eyes and grumble about her giant advance, or is it better to take a more generous, big-tent philosophy?

I have to confess, I didn’t know anything about Snooki’s book deal until now. In my world, writing is art, but books are commodities, and these realities have to coexist. None of us can help grumbling every now and then, but the only thing we can control is our own work. And maybe Snooki’s earnings will enable her publisher to discover an unknown writer or two.

Or maybe Snooki has a great story to tell. You never know.

Further Links and Resources

The hardcover edition