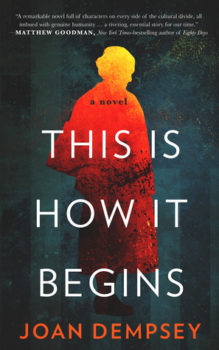

Joan Dempsey’s debut novel This Is How It Begins (She Writes Press, 2017) is a powerful and moving exploration of a flashpoint in contemporary America: the organized efforts of the Christian right to advance “religious freedom” laws in conflict with those who view such efforts as seeking to institutionalize bigotry. What’s striking about Joan’s handling of this volatile issue is her ability to depict the complexity of human nature on both sides, and how each camp feels fully invested and morally justified in their beliefs.

At the center of the book is the abrupt dismissal of educators across the state of Massachusetts who are gay and lesbian. Mirroring the current controversy over “Religious Freedom” laws, these firings are on the basis of “religious liberty” and are part of a highly organized campaign orchestrated by a network of fundamentalist Christian churches. Among those fired is Tommy, a thoughtful teacher of AP English, who is the grandson of the book’s protagonist 85-year-old art professor Ludka Zeilonka. The wave of threats, harassment and assault that follows Tommy’s dismissal forces Ludka and her husband Izaac, to reckon with their own past in Nazi-occupied Warsaw. What they see are the stirrings of all-too-familiar hatred and suspicion, and how easily people can become enablers of violence, how even the well meaning can be pulled into dehumanizing others with devastating consequences.

Over a decade ago, Joan and I met at the M.F.A. program at Antioch University, Los Angeles. Since then, she has become not only a close friend, but one of a handful of people I trust to read my drafts. Joan is a writer whose serious commitment to craft is matched by her deep compassion for her characters. The following interview took place via email.

Interview:

Dawna Kemper: Let’s start with Ludka. While she is, strictly speaking, on the periphery of the core plot around the dismissal, she still feels like the heart of the book. Do you see her as the protagonist? How so? Why the decision to use an octogenarian for an issues-based narrative? What particular challenges came up for you?

Joan Dempsey: Oh, no question whatsoever! Ludka is absolutely the protagonist. Honestly, the only real decision I made about Ludka was to allow her into the narrative; this was supposed to be a novel about her son, the senator, but she kept muscling her way into the story, and the story didn’t come to life until I let her in. Once I did, she took over. All subsequent decisions from there on out were less like decisions, and more like acquiescences.

Joan Dempsey: Oh, no question whatsoever! Ludka is absolutely the protagonist. Honestly, the only real decision I made about Ludka was to allow her into the narrative; this was supposed to be a novel about her son, the senator, but she kept muscling her way into the story, and the story didn’t come to life until I let her in. Once I did, she took over. All subsequent decisions from there on out were less like decisions, and more like acquiescences.

I didn’t deliberately set out to write an issues-based narrative, although I knew I wanted to write something political, set in part at the Massachusetts State House, where I lobbied for many years on animal welfare issues. The issues in the novel arose organically as I wrote, and were all tied up in Ludka’s personal journey as an octogenarian coming to terms with her past. The political story revolving around her grandson, while certainly central, was in some ways merely the catalyst that compelled her to face her demons.

With Ludka, correctly capturing her psychology and her voice were the two biggest challenges. She’s a psychologically complex woman—a Catholic, a survivor of WWII, a rescuer of Jews, an immigrant, an artist and a strong personality who has willed herself to forget her past, to name just a few traits. The rescuer personality alone is a fascinating one, and I dog-eared Dr. Eva Fogelman’s incredible book Conscience & Courage: Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust. To get Ludka’s voice right, I spent countless hours watching Shoah Foundation videos of English-speaking Polish WWII survivors recounting their stories of the Holocaust. All of it was fascinating!

Speaking of characters, there are so many ways that characterization—of Ludka, of Tommy, of Warren Meck, et al.—could have fallen right into stereotypes, yet you manage to avoid this. Given the themes of this book, that seems especially important. Can you talk about this process, especially with a character like Meck who could so easily become a cardboard “villain”?

I’m so glad to hear you say I avoided stereotypes, since getting the characters right was my primary concern. I worked incredibly hard to bring each character fully to life as a unique person, and only over time, by fully embodying each of them, did I manage to do this.

I’m laughing, too, since you went on the Warren Meck journey with me, and you understand that he was the hardest character to write! He started out as a complete caricature—like a cartoon character standing among flesh and blood people, something out of Who Framed Roger Rabbit! The first thing I did was give him a dog. This helped, but wasn’t quite enough. Then you and other trusted readers pointed out that a 37-year old Christian guy would have a wife and kids. I didn’t want to hear this because I’d written a full draft by that time, and adding them … ugh! But you were right, and I did add them, and that was a turning point for Meck. The final piece of getting him right was finding something I could truly relate to about him so I could really like the guy, and that thing was politics, and lobbying. I loved my work as a lobbyist, and Meck did, too, so that was my way into his heart and soul. After all of that, Meck finally came to life.

This leads me to the book’s point of view. Was the narrative always omniscient? Or was that a later decision?

The point of view began as third person (close to the senator), but I quickly realized I wanted to get inside the hearts and minds of more than one primary character. A central goal for me with this book is to help my readers develop empathy for the characters who are most unlike the readers themselves. If someone reads this book and ends up questioning her own beliefs, I’ll feel I’ve done my job well. So far, I’m hearing from both liberal and conservative readers that I’ve succeeded in this regard. I’m particularly glad to hear that early Christian readers have said they were concerned before reading that the novel would be a diatribe against them and their beliefs, and they’ve been pleasantly surprised to find that’s not the case. And from liberal and LGBTQ readers I’m hearing that I made them think, and that they ended up really liking Warren Meck.

I’m personally a “shades-of-gray” kind of person, and I rankle at the stark divisions we all allow ourselves to create. I wanted to illuminate the humanity in each character, and to show that every single one of us has the capacity for bias and prejudice as well as for love. The omniscient point of view allowed me to do just that.

I remember when you began sending out the manuscript, well before last November’s election, that the responses from agents were high praise for the writing, but a sense that “We’re past that now.” It’s interesting that the book is suddenly “timely”—given the rise of visibility of neo-Nazis and the KKK, emboldened by people now in political power—when you were writing it long before the current turn of the political climate. I’m reminded of activists, particularly in the BLM movement, pointing out that this kind of hate is nothing new; it’s just that the average American suddenly notices when it begins hitting close to home. How do you see the book in conversation with or as a response to this idea of Americans’ complacency and/or blind spot to discrimination and systemic oppression?

I do hope the book is in conversation with our “blind spots to discrimination and systemic oppression.” Anyone who’s ever been part of a minority understands discrimination, and those in the majority—even the most educated, well-meaning folks—often don’t fully realize the extent of bias that exists.

In the novel, when Tommy, Ludka’s grandson, is gay-bashed, Tommy’s father Lolek, the Massachusetts senate president who has championed LGBTQ causes throughout his career, and who feels he knows everything there is to know about gay rights, tells Tommy that because of the violence, things have changed.

“What’s changed?” said Tommy. “What do you think is different?” He waved a hand over his bruised face and touched his tender ribs. “This? This is nothing, Dad. This is nothing every gay man doesn’t fear every day of his life.”

In this small moment, Lolek is surprised to discover how terribly much he doesn’t know. I think it’s like this for most folks who haven’t directly experienced someone’s judgement or hatred.

When agents passed on representing the book, the Supreme Court had recently passed gay marriage into law for all Americans, and they were concerned that people wouldn’t believe the violence in the novel. What they failed to understand is that no law will prevent personal bias, prejudice or bigotry, and that every major stride in the quest for equality is followed by a fierce backlash. Now, in the wake of Charlottesville, where among other things the white supremacists chanted, “Fuck you, faggots,” as if it were a high school football cheer, I think we can all agree we’re not past that now.

And in the novel, no one is immune from their own personal biases. They rise up in each and every character, just like they do for all of us in real life, liberal and conservative alike—I hope the book helps readers understand that.

One of the recurring elements I noticed was the importance of language. In the book we have competing sides whose interpretations of not only the law, but of the Bible, diverge. Terms related to war, liberty and patriotism are habitually co-opted. Pastor Royce greets his congregation with “Good morning, Redeemers!” underscoring the justification of their cause, and declares that it is “America under siege.” He later bristles at how the word “tolerance” is now interpreted, and refers to The American Heritage Dictionary as “that other great book.” So there’s a recurring theme here about how issues are framed, especially in conflating “Christian” with “American.” As you were writing the book, what were your thoughts about the power of language and how it’s reshaped to advance various points of view?

Language is everything. I first learned this not after I became a writer, as you might expect, but when I was a lobbyist. When drafting and reviewing legislation, two of the most powerful words that exist are also two of the smallest: “may” and “shall.” Swap one of those words for the other, and the bill’s entire meaning changes. “May” means “if you wish” and “shall” means “you must”; if a bill becomes law and that one word is wrong, the consequences can be calamitous.

In writing the novel, I had to create an entire political campaign for Meck and his Christian team, which in part meant thinking hard about how they would use language to advance their cause. I have to say, that was great fun (it allowed me to return to being a lobbyist for a time)! So the bill Meck wrote, which in practice, should it become law, would allow school boards across the state to discriminate not just against LGBTQ teachers, but any “type” of person to whom the board might object, is titled, “An act further protecting our schoolchildren.” Who wouldn’t want to protect schoolchildren?

In our current climate, the “religious freedom” bills that are being considered and passed at both the state and federal level right now are not solely about protecting religious freedom, although this is what the bill’s sponsors sincerely believe. What American doesn’t want to protect the cherished, foundational American right of free religion? But like Meck’s bill, these current bills, too, would allow religious individuals to discriminate against not only LGBTQ folks, but anyone else they deemed objectionable based on their religious beliefs. The language of this legislation doesn’t spell that out, of course, but it’s there all the same.

Language, in other words, can be used towards any end, and it’s up to us to scrutinize it so we fully understand its intentions and potential impact.

For me, in a narrative with so many compelling dramatic scenes, one of the most riveting passages in the book was when Ludka and Izaac return to Warsaw. The neighborhood they grew up in had been destroyed by Nazi forces, but the Poles reconstructed it in exacting detail, so that what Ludka and Izaac return to is a recreation—a “resurrection,” as the book says—of the place they knew. Can you talk a bit about this, and about how your own time in Poland (and further research) inspired you?

One of the fascinating things about the month I spent in Warsaw (thanks to a generous grant from the Elizabeth George Foundation) is that the area where I stayed, called “Old Town,” was built atop the rubble from WWII. As a result, that area of the city is at a higher elevation than it used to be. I couldn’t stop thinking about that as I walked around the neighborhood—how the old city, and everything it contained, was buried beneath the streets. At the same time, as you mention, the area was rebuilt in exacting detail, so it has the feel of a city older than it is, and it looks just like the original. I kept thinking about what it would be like to return to that city after more than sixty years, to find it simultaneously familiar and also not quite right. And also how that restoration demonstrates the stubborn resilience of the Polish people, who by “resurrecting” their city, tried in some ways to cover up its terrible past.

This covering over of the past is also what Ludka and her husband Izaac tried to do. They rebuilt their lives in America, on top of their own personal, psychological rubble, and hoped they’d never have to dig into it again. That, of course, isn’t the way life works, and the novel is largely about Ludka’s journey into uncovering her past. I doubt I would have understood this as thoroughly had I not gone to Warsaw.

The other major inspiration from being in Warsaw was my visit to the Jewish Historical Institute, which houses the Ringelblum Archives. Emmanuel Ringelblum was a historian during WWII who recognized the singular moment in which he was living, and the importance of preserving its history. He organized a group of people to document life in the Warsaw Ghetto, and buried that documentation in huge milk cans and other containers so that after the war they could be retrieved and preserved; of course they became a major contribution in the ongoing effort to “never forget.” In the novel, Ludka sketches scenes from the Warsaw Ghetto to contribute to these archives, and it’s those sketches that ultimately force her to confront her past—this was my tiny tribute to Ringelblum’s foresight and heroism.

One of the things I love about the book is that it begins and ends with art. Why was this so important to you in telling this story?

First, it was important to Ludka, who of course is an art historian as well as an artist in her own right, albeit one who gave up her art because of the war.

Next, and I don’t have any idea why this is the case, art appears to me when I’m writing, fully formed. For this novel, and in the same way Ludka muscled her way into the narrative, Alexander Roslan’s “most famous painting”—Prelude, 1939—showed up and demanded air time, too. I could envision the entire painting (and it’s “as long as a train car, as tall as an average-sized man!”) as if it were hanging in front of me. I remember when you read an early draft you Googled it because you wanted to see it—that made me so happy!

Finally, during wartime, art is a target of the enemy. To paraphrase Ludka, to steal or destroy art is to steal or destroy the soul of a people, of a culture. Hitler famously set about systematically stealing the art he deemed worthy for a vast museum he was planning, and destroying the art he deemed degenerate, most notably anything contemporary, and nearly everything Polish.

As for specifically why the book begins and ends with art, that’s something for the reader to discover!