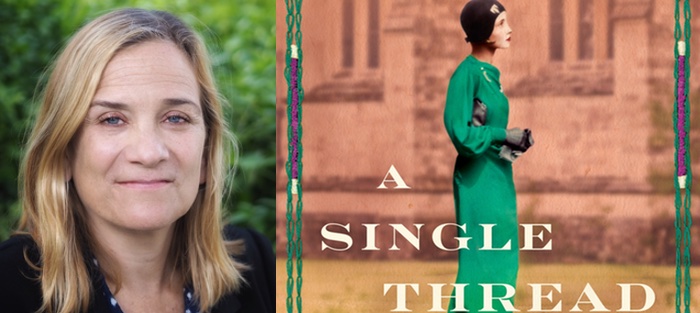

I always look forward to reading new books by Tracy Chevalier. Through clear and unaffected prose, she consistently crafts intriguing stories populated by a cast of luminous characters. A Single Thread, her tenth novel, released September 17 by Viking, is no exception.

Born and raised in Washington, DC, Tracy moved to London after earning a bachelor’s degree from Oberlin College. Before writing, Tracy was an editorial assistant with Macmillan’s Dictionary of Art, and then a reference book editor at St. James Press. She earned an MA in Creative Writing from the University of East Anglia and wrote freelance, until the world-wide success of her second novel, Girl with A Pearl Earring—which was adapted into an Oscar-nominated film and will soon become an opera in Zurich—allowed her to write full time.

Nearly two decades after Girl with a Pearl Earring, A Single Thread explores what it meant to be one of the millions of British “surplus women”—females with little likelihood of marrying after so many young men were killed in World War I—who were the objects of pity, scorn, and fear. Set in 1932, the story focuses on Violet Speedwell, a 38-year old typist who lives with her selfish, suffocating mother and still mourns the wartime deaths of her fiancé and her brother. When a job transfer opens up, Violet moves from her family home to a boarding house in Winchester, though the cost of her independence is a lonely, penny-pinching life with few thrills. She finds solace with a group of women charged with embroidering kneelers and cushions for Winchester Cathedral, including the real-life leader, the unflappable Louisa Pesel. Through Violet’s association with this group, she discovers a community she didn’t have at home, the core of her personal values, and what it means to be a friend.

This conversation was conducted over the phone.

Interview:

Kate Lemery: When you first began writing, what were your short stories about and who did you model yourself after?

Tracy Chevalier: When I first started writing short stories, they were all contemporary. They were modeled after Carson McCullers. There was a bit of Hemingway in there, too. All the big ones. I always felt I wasn’t a particularly good short story writer, but I was treading water until I had a big idea for the novel.

Having said that, I have huge respect for short stories—I just find them much harder to get right than a novel. A novel is a lot baggier and it gives you more leeway to go on for too long or to make mistakes. Whereas in a short story, every sentence, every word, matters—and that’s very hard. I think it’s easier to write too much than it is to write exactly the right thing.

Your website lists the books you read, often an ambitious five a month. How do you choose?

The short answer is it comes from personal recommendation, reviews, and stuff that publishers send me that looks interesting.

I choose books not randomly but I’m rather like the way I am with television. I never just turn on the television to see what’s on. In the same way, I often go into a book store to see what’s there, but I’m also looking for specific things.

I keep a notebook of things that either have been recommended or I’ve seen reviews of. Or often, friends suggest books, and those I write down, too. I’m looking at my pages now, and I haven’t read any of these things. [Laughs] There’s so much to read out there. It’s painful.

Once you’ve begun reading a book, do you feel committed to finishing it?

Once you’ve begun reading a book, do you feel committed to finishing it?

Here’s how I look at it: If I’m lucky, I read a book a week, which is about fifty books a year. I’m fifty-six, and if I’m lucky I might live thirty more years. So, thirty times fifty is 1,500 books. That’s not very many when you think about how many are published in a given year, how many classics there are.

So, why would I waste my time on something that’s not giving me pleasure, or that I’m not finding well-written. I used to feel like I had to finish it, but now—no way! I don’t want to feel like I have to give up one of those precious slots.

Your Goodreads profile says that Anne of Green Gables by LM Montgomery would be the book you would’ve taken to a desert island in your childhood. What made it important to you back then?

I was ill with the flu. I was ten or eleven years old, and my stepmother got it for me to entertain me. And it was incredibly entertaining. I’ve discovered that some of the books I’ve loved the most I’ve read when I’m ill in bed because I can give them that close attention. I can read them in one big gulp rather than eking them out over the week on the bus or at night before bed.

But also, the book has great storytelling, lots of drama. The characterization is beautifully done and the integration of character and landscape is beautifully rendered. I like a good story, too, and you really want to know what’s going to happen next to Anne.

What are books you often give out as presents for adults and for children?

It varies. It’s not one specific book, because I’m always finding something new and different. Also, I really tailor it to my friends’ taste and I’m not going to give the same book to each person.

The book I’ve been recommending to people a lot is Reservoir 13 by Jon McGregor. It’s a novel about a thirteen-year-old girl who goes missing on the Moors in the north of England when she’s on vacation with her parents. The book focuses on the village where she goes missing and the community who lives there. It’s told in this strange, almost sing-song, flat voice, and each paragraph—and sometimes even within a paragraph—it switches from one character to another. There’s a cast of thirty and you gradually build up this view of the community and how the disappearance affects them. I don’t usually go for experimental novels, but this one is fabulous.

You typically choose a different notebook for each novel you work on. Can you describe the notebook you used for A Single Thread and why it felt right for this project?

Usually, I take great pleasure in finding a notebook that’s going to match the subject matter. And this time, for some reason, I was in a hurry. I hadn’t found the right one, I had started my research, and I couldn’t wait for the perfect notebook. So, I just grabbed one that I had. It’s the first time though, and it felt a little sad.

Art is a theme in so many of your novels. Your novels lift art up beyond something merely beautiful to look at, and it becomes a means to channel personal growth or awakening. When did you first awaken to art?

I think I first woke to art when I saw the painting of Girl with a Pearl Earring, when I was nineteen. I had seen art before. I remember my history teacher sending us to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and we had to fill out this sheet so she’d known we’d seen all the things she wanted us to see. She was teaching history through looking at painting. So, I know I went to the National Gallery and saw some Vermeers then, but I don’t remember them at all from when I was sixteen. [Laughs]

But when I was nineteen and visiting my sister, I saw a poster of Girl with a Pearl Earring on her wall, and I fell in love with it. Then I went back to the National Gallery and looked at the Vermeers there, and I went to the Frick and the Met in New York to see the Vermeers. I think that got me more interested in looking at art in general. Now, every time I go to a new city, the art gallery and the cathedrals are the places to visit, but since those late teenage years, I’ve really appreciated how art from the past can open a window of what people were thinking and what they were like, so I’ve always been interested in art in that way.

What are some of your current favorite artworks, in any medium?

I’m still a sucker for Vermeer and Rembrandt, the two big Dutch guys. In current work, there’s a wonderful sculptor in England called Antony Gormley, who makes statues of himself and places them in interesting places. He’s about to have a retrospective in London, and I can’t wait to see that.

I’m also really looking forward to soon seeing the work of Kara Walker, an African American artist. I saw an exhibition of her cutouts in London a few years ago, and I was really impressed by them. I live in London, and the Tate Modern is a big, modern gallery here that has been made out of a disused power plant on the river. They have a collection of modern art, but they also have a turbine hall, a big open space, and they commission a different artist each year to fill that space. Kara Walker is going to be putting something in there in November for several months. I can’t wait to see what she does. A few years ago, she did that statue in New York, in sugar.

Sugar Baby, right?

Right! And it’s really interesting because the Tate family, the Tate company, made sugar and they were heavily involved in the slave trade back in the day and I’m wondering if she’s going to do another sugar model. It would be amazing in that space. So, that’s what I’m hoping for. I’m always looking for new and different artists.

J.K. Rowling said she wrote Chapter Nine in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire more times than she could remember, and that it “almost finished her.” Do you have any chapters in A Single Thread or previous books that you wrote many times? How did you know when that difficult passage was finished?

I don’t recall a specific scene that I wrote many times, but I know for me the hardest part of the book is almost always the ending.

The endings reveal things that the reader discovers—those have to be really handled carefully. Sometimes, a character learns something in the end, and they respond to it emotionally. But you can’t always have them respond immediately. The characters need time to take it in, and so does the reader. The way you create that time is with words. So sometimes you actually have to write something that doesn’t need to be there for the meaning. It might seem those extra sentences are filler, but they give readers time in which to absorb, and for the character to absorb, what’s gone on, or what’s been revealed, or what they’re thinking.

And endings are also hard, because readers have expectations. They want to be satisfied, and to have it all tied up, but they also want to be surprised. So, a good ending is a combination of trying to have it be surprising, but also something that makes sense. This is almost impossible, because usually the reader is anticipating what is going to happen, but if it’s really and truly a surprise, the ending might be something that doesn’t fit, and is, therefore, not satisfying, because it’s so surprising. So, it’s a real balancing act.

What do you know now about the craft of writing that you didn’t know when you worked on your first few books?

[Laughs] A lot! With my first novel, The Virgin Blue, I would write a bit and would research alongside it. I’d get a quarter of the way in, and then I’d have a big thought about something. So, I’d go back to the beginning, tear it up, and start again. But it felt like it took a long time to write to the end, because I kept undercutting the process. Now that I have more experience, I know it’s important to get a draft down, then you can reshape it. It’s quite time-wasting to go back over and over again restarting.

Another thing I’ve learned is that I usually have a crisis of confidence two-thirds or three-quarters of the way through, and that that’s normal. I almost always have a point where I think, “Oh, no. This is boring. This isn’t working. Why am I writing about this?” My husband’s really good when I start making that complaint. He says, “Oh, you’ve reached that point. That happened to you the last time, remember?” So, I’m not quite so rattled by my crises of confidence as I used to be. Self-doubt is actually part of the process, so I know to just keep going.

It’s reassuring to hear that even established writers such as yourself have these self-doubts.

I think we all do, but I think most established writers just don’t talk about it.

At this stage in your writing career, how many first readers do you use before turning a manuscript into your agent or editors?

None. My first readers are my agents and editors.

I was in a writers’ group through Girl with a Pearl Earring and then after that I didn’t have time. Once I started getting contracts, and there was a deadline, I didn’t have time to go through my writing with other people. In an ideal world, maybe I would have more readers.

You know, when you asked before what have I learned, I’ve learned that editing is writing, and the first draft is just part of the whole process. And evaluating your own work and being really hard on each sentence—asking, “Does each of these words in this sentence actually need to be there? Is it adding anything? What about this paragraph? What about this character? What about this whole chapter?”—is really important. And I know how to do that with myself, and in the beginning I didn’t. When you’ve done it long enough, you learn over time what this process needs to be and how to edit yourself. And I’m also open to my editors challenging me and making suggestions. I’m also not so arrogant to think that only I know best whether something is working or not—because I don’t. A book only works when a reader understands it, and that is not always what a writer can judge.

Your novels are populated with entire casts of three-dimensional characters. What do you do to channel a character and bring out their humanity when you’re writing about them?

I live with them for a long time in my head. When I first start writing about a character, I don’t know them that well. It’s through the process of writing of putting them in scenes, and contemplating them—when I’ve spent more time with them—that they take on more flesh.

When I start writing, I have a lot of characters that I’m not sure what their place in the novel will be. For instance, Gilda Hill in A Single Thread. At first, I thought she’d be one of the ones who gets Violet to come to the embroidery group, but I didn’t know if she was going to become more than that. I didn’t know the whole story between Gilda and Dorothy was going to happen at the time. Dorothy became more important as I put more flesh on her.

And some characters recede as I put more flesh on them. I think I don’t really need them; they’re not giving me anything. Or they’re there for a particular effect, and that’s it. At one point I thought Violet’s landlady, Mrs. Harvey might be a much bigger influence on Violet, but then I decided she was enough like Violet’s mother that I didn’t need to hammer that home.

Writing is a delicate process of moving characters around to see how they fit in the big picture.

Fylfot, an Anglo-Saxon symbol that was adapted into the Nazi swastika, was a new word for me. The incorporation of this symbol into one of the embroidered kneelers becomes a source of tension between two of the main characters. What did the real-life Louisa Pesel, founder of the Winchester Cathedral Broiderers, think of this symbol?

We have no idea. All I know is that she made a model for the fylfot to be on the cushion, and that got made and that they’re on the cushions, and that they are on this particular statue in Winchester Cathedral. What we do know about her is that she was known to copy particular motifs from the Cathedral and from other places and put them on her designs. Once I saw the fylfots on the Cathedral cushions, I was horrified, because in everything I’d read about her she seems like a noble, nice person, and I have a hard time knowing that she would put swastikas on the cushions. But then when I discovered the fylfots on this much older statue in Winchester Cathedral, I was delighted. I knew then that she wasn’t copying the Nazi symbol, but a much older symbol. So, then I had to decide whether she was doing it deliberately as an act of defiance or not. She didn’t say, so I had to interpret it myself. And I decided to interpret it as an act of defiance.

Your website mentions you’re working on a story about Venetian trading beads, which follows one family from the fifteenth century to the twenty-first. Can you tell us more about that project?

Just a little bit because I’m still at the early stages of research. I became interested in the beads because somebody told me about them and said that they have really interesting stories about them—not just how they’re made, but what they encompass in terms of value. Venetian traders used them instead of coins with other countries because coins didn’t mean anything in Africa, or South America, or to Native American Indians. A coin is only of value in the country it’s minted at, usually. So, traders had to find other things to trade with. What’s so interesting is that usually you think of trade as sugar and guns and blankets, and useful stuff. Glass beads are actually pretty cheap to make, but people in Africa and in South America had no idea how to make glass. It was new and different for them, and absolutely beautiful. The book in some ways is going to be about value and how a little green or blue glass bead is going to mean something to someone on a West Indian island in a way that it means very little to someone who’s a native to Venice.

That sounds fascinating. I can’t wait to read it.