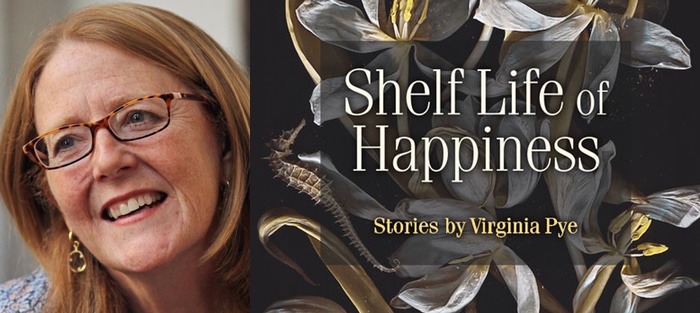

Virginia Pye is the author of two novels, Dreams of the Red Phoenix (Unbridled Books, 2015) and River of Dust (Unbridled Books, 2013). Both take place in China and involve historical events; both evolved from her grandparents’ experiences as missionaries and her father’s having been born and raised in China. She now has a collection of stories, Shelf Life of Happiness, due out from Press 53 this October.

I’m in awe of any writer who can pull off both novel and short story. I was told in workshop years ago that I’d write novels. I was afraid of such ambition as I submitted story after problematic story to the group. Virginia Pye’s stories are concisely drawn with an enviable array of diverse characters. Her plots operate on an emotional plane: a slight shift in perspective, an abrupt act, an unexpected response move the stories forward. There are no grand gestures, only the circumstances of a life. William Trevor described the short story as “the art of the glimpse.” What a feat to go from the long gaze of the novel to that intimate glance.

With an MFA from Sarah Lawrence College, Pye has taught writing at New York University and the University of Pennsylvania. Her essays and stories have appeared in the North American Review, The Baltimore Review, The Rumpus, Literary Hub, Huffington Post and The New York Times. Noteworthy too—Virginia Pye kept her cool when she ran into Mick Jagger at a Shanghai bar.

Interview:

Janyce Stefan-Cole: Reading your stories I feel as if I’m peering into your characters’ lives through a window, almost inappropriately compelled to keep watching. Yet these quintessentially American stories are packed full of familiar places and situations any of us might encounter. You are wonderfully observant. How did you find these stories?

Virginia Pye: Without trying to sound too mystical, I feel that these stories found me. If I notice something that’s quirky or unresolved—a little gem of experience that captures life’s ironies or conundrums—I start to imagine resolving it in a story. Though, of course, fiction never resolves anything. Instead, it opens more avenues of thought about life, rather than narrowing them down. But still, I use fiction to explore small moments that have leapt out at me as rich with possibilities.

You have said, “Fiction gains its full scope when an author takes a daring imaginative leap fueled by empathy and understanding.” Orhan Pamuk speaks of the writer’s compassion for his characters. Yet there’s an argument afoot that a writer ought to stick within his or her—especially ethnic—experience. Well, first off, that would preclude murders from most fiction, or a female writer creating a male protagonist, or possibly, too, books written about a foreign country in a different era. To me your quote perfectly states the writer’s gift: imagination and empathy. (Which does not imply either is easy to exercise.) Can you comment?

You have said, “Fiction gains its full scope when an author takes a daring imaginative leap fueled by empathy and understanding.” Orhan Pamuk speaks of the writer’s compassion for his characters. Yet there’s an argument afoot that a writer ought to stick within his or her—especially ethnic—experience. Well, first off, that would preclude murders from most fiction, or a female writer creating a male protagonist, or possibly, too, books written about a foreign country in a different era. To me your quote perfectly states the writer’s gift: imagination and empathy. (Which does not imply either is easy to exercise.) Can you comment?

Fiction relies on the suspension of disbelief, and to achieve that is not as easy as it sounds. To get a story or character right, you have to really know your subject, which doesn’t mean knowing every detail, just the right details. The essence.

I agree with the perspective that writers from dominant cultures must bring an especially sensitive and self-aware approach to telling the stories of people who have had vastly different life experiences from the author’s own, and who have perhaps faced oppression that the writer’s own group may be responsible for. That’s what I tried to do in my two novels. When a writer does choose to portray someone from an oppressed group, she needs to be aware of the bias with which she approaches her story. Compassion and empathy and respect must be the guide.

There’s a passivity running through many of your characters. In “Her Mother’s Garden,” Annie is ever stunted as the garden thrives. This is an interesting take on mother and garden as metaphor: nourishing forces become almost like kudzu, invading and choking the spirit. A similar passivity engulfs Sara in “Crying in Italian.” She seems ready to suffocate with unhappiness but, unable to confront it, she wanders off from her children to watch a couple making love among the Roman ruins. In “New Year’s Day,” Jessica horrifically speaks her mind to the last person to connect with a murder victim, behavior that disrupts Jessica’s sense of who she is.

I find truthfulness in these characters’ passivity, their indistinct dissatisfactions. Tell me about that, where these characters come from. How do you know them so well?

Actually, this question follows nicely on the one before it, because I think that passivity I explore through my characters comes out of a feeling of separateness and disconnection from the world. My characters often feel they aren’t a part of the mix. They’re not rubbing elbows with others who are unlike themselves. They’re on the outside. This could be because of being raised in the suburbs; I’m the child of intellectuals; I was the youngest in my family by many years and felt like an only child; and I’m a writer—whatever the cause, the point is, I can relate to feeling not connected enough.

My characters—especially in my novels—often make foolish choices to break free from that feeling of being removed from life. Sara, in the story you mention in the Roman ruins, is literally heading off the path in order to find more passion and more life-giving feeling. My characters create conflict, they take journeys, they convince themselves they are finally prepared for what the world has to offer them—in other words, they plunge in, for better or worse.

The stories “Redbone” and “White Dog” involve older male artists who have or will achieve a measure of success that conflicts with every other part of their lives. Artists sacrifice for their work, and the personal—especially the family—often suffers. There is the suggestion, too, of a time when artists were viewed as larger than life—dedicated, forceful but flawed—and that that may no longer be so.

Do you believe the artist is a diminished force in society today, possibly because of the sacrifices involved in what could be called, without pointing fingers, anti-heroic times?

Actually, I think the artist today is as important, perhaps more important, than ever. Artists have always taken up the mantle of social activism and do so crucially at this time.

I think the two male artists who you mention are actually admirable, though cranky and narcissistic, especially the older one in “White Dog.” He has a philosophy about his work that I try to aspire to. At one point in the story he says that what matters in life is “the lover’s quarrel with the work.” He has dedicated his life to getting it right. He believes in the dab of paint on the canvas, the necessary imperfections required by art, instead of the sanitized version of things that so many non-artists (like the gallery owner in the story) try to pursue. He wants life with all the messy parts, and yet, ironically, he strives for it by staying in his studio year in and year out. To me, that’s pretty heroic.

Nathan, in “Shelf Life of Happiness,” is relieved he won’t have to become lovers with the beautiful, connected Gloria. It takes a stranger from the Ukraine to unstick an awkward moment, in “Easter Morning,” of a young boy harboring a dead bird. Keith, in “Best Man,” literally needs direction from the dead.

Some of your characters seem adrift in their fates. Would you say you had a sympathetic yet pessimistic view of those lives?

I think that by the end of each of those stories, despite whatever ways the main characters have felt limited in their lives or lacking in courage, they rise to meet the challenges set before them. They shrug off their own weaknesses and become better people. At least that’s how I intended them to be seen. I am sympathetic to them and maybe even optimistic. They’re weak, but they strive to be strong. That’s pretty much all we can hope, I think.

An exception is the twelve-year-old skateboarder, Patrick, in “An Awesome Gap,” who shows resolve and grit: “No one in his family got it that you had to live in the moment and do what you love to do.” His father works hard to “pay for stupid stuff.” There’s a terrific tension between this unfiltered boy and his father—the growing gap not just between father and son, but between raw power and compromise. I’m thinking of Freud’s Society and Its Discontents: the effort to reach our full potential while trying not to be twisted in the kudzu of constant compromise. Is it correct to suggest your stories reflect a sense of struggle for self-realization?

I think that’s a good way of putting it. The boy in this story, like the older artists, has a mission he’s trying to accomplish. He wants something very badly—to be a good skateboarder, even a great one. That striving makes him an artist. I admire that in people. How, whatever your field, you might have in your mind a higher level of accomplishment or self-definition you’re trying to achieve. Ambition can be seen as bad, or selfish, but if it comes with a greater self-understanding, then it’s good. So, yes, my characters, like so many characters all the way back to Ulysses, struggle to achieve their better selves.

Finally, you have a book coming out! Always a nervous thrill, the realization of a book, a need met, your words and thoughts will be read. Which satisfies Virginia Pye most, writing a book or seeing it realized? Both, of course, but I ask this because the challenges of publishing are so much greater now, and I think the writer inevitably confronts the question: Would I continue to write without being published—assuming self-publication for one reason or other is not an option?

For the longest time, I wrote without being published, so I know all about that. I had my first literary agent when I was twenty-seven but my “debut” novel, which was really my fifth written, was published when I was fifty-three. I can write without a guarantee of being published and it’s important that all writers can, especially, as you say, in this fickle, difficult market.

But I’m very happy and satisfied when a book does finally come out. The stories in Shelf Life of Happiness were written and published in literary magazines over a full decade. They capture how I’ve thought and what I’ve cared about for years. To finally get to share them is a gift to me, and, I hope, to the reader as well.