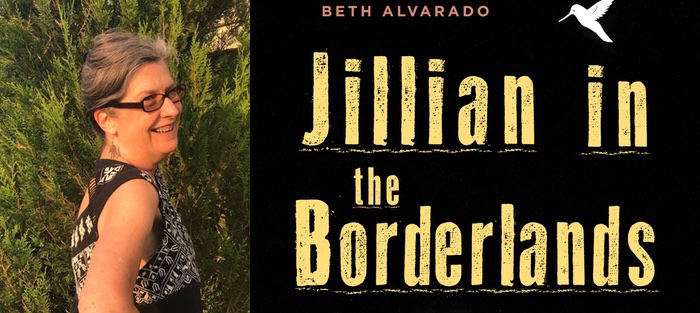

Beth Alvarado and I overlapped at University of Arizona’s MFA program in Fiction. When I started the program in 1987, she was in her second year and she was already legendary. When I took Buzz Poverman’s famous memoir class, he encouraged us to read some of the products from prior semesters, memoirs by other students. I showed up at his office hours and asked if there was a particular one he would recommend and he handed me a memoir by Beth Alvarado. “Read this,” he said.

Beth and I reconnected in the spring of 2013 when I reviewed her memoir Anthropologies for Carmel Magazine. Beth’s husband Fernando had died in January. They’d been married for forty years. I knew Fernando only through Beth’s nonfiction—the memoir and various essays—and that was a really good way to get a sense of him. You get to know Beth’s characters and you come to love them. That’s how I know and love Fernando.

Jillian in the Borderlands (Black Lawrence Press) would not have been born in Beth’s mind, were it not for Beth’s early inclusion and immersion in Fernando’s Mexican American family. They married so young, it’s as though she was raised in that family, and then raised her own two children as a subset of that family. The characters in these linked stories and the situations, the perspectives and possibilities, Beth says, are a result of her immersion in the culture, via the Alvarado family. So we have Beth, Fernando, and his extended family to thank for the birth of this rare book.

Jillian in the Borderlands is not what you expect. The stories are complicated, with multiple voices, and rich access to the spirit world. Even though Jillian is mute, we’re often in her head and her thoughts are eloquent and elegant—she has an advanced vocabulary and is even multi-lingual, but she just doesn’t speak. Some of the situations contained in these tales are dire, but the overall effect on the reader is delight. Amidst unsavory things like infidelity, accidents, molestation, deportation, separation of families, drug cartels, and toxic waste in the water table, Alvarado gives us magic, escape, healing, triumph, rescue, redemption and hope.

Here’s one of my favorite passages, a beautiful evocation of love and trust between mother and child. From “End of Days:”

Jillian wants to run back to her grandmother’s apartment and hug her mother. She can’t imagine her mother leaving her alone on the street like this. She can’t imagine her mother sending her away, not even if she were starving; not even if someone was pulling her mother’s fingernails out with pliers, would she send Jillian away. No, Jillian is sure. If she was starving, her mother would pick plants from the desert and feed her; if she was drowning in an ocean, her mother would jump in and become a life raft; if she was falling out of a plane, her mother would become a parachute; if a man was shooting a gun at her, her mother would step in front of the bullets and, like Wonder Woman, zing them back at him with her furious kung fu wrists; if a speeding car was hurtling down the street and Jillian was standing in the middle of street and did not see or hear it, her mother would hold out her arms and shoot rockets of anti-gravity energy out of her fingertips and make the car fly up into the air and over Jillian; if a burglar came into the house in the dead of night, her mother would wake up instantly and konk him on the head with a cast iron skillet; if a man was looking at Jillian in a bad way and following her on the street, her mother would shoot lasers out of her eyes and blind him; if a ghost was going to suck Jillian’s breath away, her mother would stop it with one quick prayer. Oh, no you don’t, her mother would say.

And I don’t want to give too much away, but the second-to-last paragraph of “End of Days” is also stunning. I was torn over which one to quote here.

The gaping hole left by the loss of Fernando is the size of the full desert moon. I mention this because you will see peril and loss in the Jillian tales, and you will see references to this ongoing grief in our conversation. And yet despite the difficulty of some of the material we found ourselves discussing, Beth made this interview so easy. Enjoy.

In addition to Jillian in the Borderlands, Beth Alvarado is the author of Anxious Attachments (Autumn House, 2019), which won an Oregon Book Award and was long-listed for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Art of the Essay Award. She’s also the author of Anthropologies: A Family Memoir (Sightline Books, 2011) and the short story collection Not a Matter of Love (Many Voices Project Award, New Rivers Press, 2006). Alvarado has written extensively about her experiences as a Euro-American woman marrying into a Mexican-American family, and has spent most of her life in Arizona, though she now lives in Bend, Oregon, where she is core faculty at OSU-Cascades Low Residency MFA Program.

Interview:

Melanie Bishop: I want to ask about the progression of the book. Someone on social media commented on the fact that you were publishing two books in two years and asked how you had done that so quickly. You responded that it only looks quick from the publication end, that you’ve been working on these books (essays in Anxious Attachments and stories in Jillian in the Borderlands) for about a decade. How did the Jillian stories come about and were they written in the actual order they appear in the Table of Contents? Were there any Jillian tales that didn’t make it into the book? You told me that you used to read these aloud to Fernando and he loved them; how many were written before and how many after his death? How much were these stories influenced by his life and death and how much was your own love and grief woven into them?

Beth Alvarado: I wrote the first Jillian story in 2010. I was finishing up Anthropologies, my memoir, actually, and working on a few of the essays, but I was also teaching a class on the short story and one afternoon I decided to imitate all four writers—Flannery O’Connor, Raymond Carver, Grace Paley, and George Saunders—in one story. Just to see if I could. A very early draft of “The Dead Child Bride” was the result. So, of course, with four styles, it would need four narrators or points of view, and it would have to be a segmented story. I now realize, of course, that imitating the styles also influenced the content. For instance, the omniscient narrator and gothic tone of the first segment were influenced by O’Connor and the dialogue-heavy, sitting around drinking, talking about love was, of course, Carver. Imitating Saunder’s style gave rise to some flights of fancy, like a talking Deer’s Head and a Dead Child Bride, as well as the nods to popular culture. Paley gave me the emphasis on voice, the poetic compression of the last segment and, of course, the humor throughout.

What a great exercise! As a teacher, it makes me wish I had a slew of fiction students right now; I would make this an assignment. Then we would exchange stories and people would have to guess which authors their classmate had been mimicking. How wonderful that an experiment like that led you to this first story, which led you to everything that followed, which, ten years later, brings the world this uncommonly delightful book.

Oh, thank you. I’m glad it’s delightful—it did make me laugh, often, while I was writing it. It took me a while to get that first story “right,” but once I did, it gave me some constraints that were liberating. I loved knowing I would start a new story with either Angie or Jillian’s voice, that there would be various other perspectives, and that the segmented form would allow me to jump from character to character and moment to moment, without having to worry about plot. Just recently I’ve realized that having these various voices tell the story is actually very organic: the book is set in the borderlands, where there isn’t only one story and where voices come together and diverge and so again, I think there is a way in which stylistic choices gave rise to particular subject matter, without my even being conscious of it.

Oh, thank you. I’m glad it’s delightful—it did make me laugh, often, while I was writing it. It took me a while to get that first story “right,” but once I did, it gave me some constraints that were liberating. I loved knowing I would start a new story with either Angie or Jillian’s voice, that there would be various other perspectives, and that the segmented form would allow me to jump from character to character and moment to moment, without having to worry about plot. Just recently I’ve realized that having these various voices tell the story is actually very organic: the book is set in the borderlands, where there isn’t only one story and where voices come together and diverge and so again, I think there is a way in which stylistic choices gave rise to particular subject matter, without my even being conscious of it.

Once I had the voices, it was almost as if I were channeling them. It was like taking a vacation from the essays which were hard for me to write because I felt so vulnerable. Although both books take “facts” of my life and explore them, in the stories I was inhabiting someone else. I could allow my imagination to go wherever it wanted. I think Fernando loved the stories because they were often so fantastic and funny. It annoyed him a little to read my nonfiction because he, of course, remembered things differently than I did—but the stories riffed off of our lives and so he didn’t feel as exposed. He especially loved Marisol’s voice and Juana of God’s because they channeled many of his thoughts. “Dear Juana of God” was the last story I read aloud to him, and “Jillian Speaks” was the first thing I wrote after his death. In it, because I was writing from Angie and Jillian’s points of view, I think I get closer to an evocation of grief than I do in the essays, but it’s hard for me to know.

Oh, and yes, all of the tales made it into the book and, with the exception of “The Dead Child Bride,” they required very little revision, which is odd for me because I’m usually a heavy reviser. They were written in this order, which in a way is interesting in terms of border politics: when I began writing in 2010, Arizona had just passed SB1070, an anti-immigrant law that was then adapted by many states and, of course, by the end of the book, children were being separated from their parents at the border—so, as the politics became more extreme, they began rising more to the surface of the book.

I’m intrigued by what you say above about Fernando, that both Marisol and Juana of God “channeled many of his thoughts.” Can you elaborate?

With Marisol, I’m thinking about “End of Days,” where she points out all of the place names that are Spanish. In the book the borderlands extend to San Francisco and into Colorado; they are not just the Southwest region that we now think of as the borderlands and that view of history is definitely one I learned from him. His mother’s family had Spanish Land Grants that were taken from them during the Gold Rush. In L.A. there’s an intersection of the streets Fernando and Alvarado! We always wanted to stop and take his photo beneath the sign. Also, in “Dear Juana of God,” Marisol thinks, “Los norteamericanos, they are the only ones in the world who think that God proves Himself by granting wishes and giving prosperity,” which would be pretty directly his critique of prosperity theology, or “religion light,” as he called it, where you expect God to help you prosper as long as you profess belief in Christ. I guess Marisol represents his critical self and Juana of God his more philosophical self, especially in “Lost in the Thorny Desert” when she gives the eulogy for her Chihuahua Junie. “‘The line between body and soul is mutable, a border one crosses every day and every night, a liminal space like air over the surface of water. Somewhere, invisible to the human eye,’ she said, ‘things that seem different are really the same, como el aire y el agua son los mismos. There is a space, right on the surface of a lake, where air molecules sink into the water just as the water molecules rise to meet them. We are all, como se dice, mist. . .’” He loved reading and watching things on quantum physics and string theory and religion and always wanted to talk about those ideas, how they informed one another. I really miss those conversations.

That quote from Juana of God in “Lost in the Thorny Desert” is just magnificent. And I can imagine how much you miss the conversations you had with Fernando.

My aunt often told me that her dead husband, whom she missed horribly, came to her in her dreams and tried to get her to follow him, but when I asked something about his soul waiting for hers, she said, “I can’t hear his voice or touch him so what good does believing that do me?” I feel pretty much the same way. I miss Fernando being incarnate. I wrote out of a kind of homesickness, I guess, and out of a sickness of spirit over what was happening at the border, the dehumanization of children. We say we value children and families but, in my opinion, our policies say otherwise.

I agree. Also, I love what you said above about the writing of the Jillian stories being a vacation from the essays, and how, when using aspects of our lives as source material, there are great differences between growing/fashioning the material as fiction or presenting it bare as nonfiction. I’m familiar with all your creative nonfiction, and such a fan, but I’ve not read your early short story collection, Not a Matter of Love, which was published fourteen years ago. I’m curious if the work in this story cycle was a real departure from your earlier short stories, or if that first published collection also had magical elements? It was a real shift for me as a reader, to go from immersion in your nonfiction to these fanciful tales. The range is astounding. You sure you aren’t two people?

I’m often of at least two minds. Does that count? Not a Matter of Love was a very autobiographical collection and much more conventional in terms of the writing. Only one story was from the first person and most played with shifting third person. I liked that montage of perspectives so much that even in Anthropologies, my memoir, I played with going into other people’s perspectives by having them tell their stories or by my recounting what they remembered or dreamed. So that technique carried over into the Jillian stories—because I realized that it gave me a lot of range and it gave the reader a kind of omniscience, where she would see and understand more than any one character, where she would become the person putting the story together. I understood, from writing Anthropologies, that you need only the barest of threads to suggest a narrative arc.

I was about halfway through each book when Fernando died, and while writing an essay, I tried to be honest, and because I wanted to be honest, I had to be vulnerable. But I was also careful—I don’t know how else to say it—because I didn’t want to be maudlin or sentimental or self-pitying, all those things you are when grieving. Writing the stories gave me access to emotion that I didn’t, in my waking life, have. I still grieve, primarily, in my dreams. In my waking, essay-ish life, I hold things together. But you know how it is when you’re grieving, and you hear a song? Suddenly you start weeping? Writing the stories could be like that. Because I was inhabiting another voice, I was off-guard, or maybe in creating Angie’s loss—so, you know, the whole idea of catharsis—I could feel my own. In expressing her grief I was remembering things that, otherwise, I would not have remembered. I was given access to feeling through being empathetic? Maybe I needed to write both forms at the same time.

Would you classify your book as fabulist fiction, speculative fiction, magical realism, or something else entirely? Do you care about such classifications? Do they matter?

I prefer fabulist because it makes me think of the merging of two realities into a kind of liminal space: there is the concrete world of matter, what we call reality, but just beneath or inside or parallel to that, the realm of the ineffable. And this makes sense, in a way, because that’s just another kind of borderlands. I mean, the fact that Jillian is very open to spirits and can find lost migrants by listening for their memories or that spirits can hear and guide her—that goes to Mexican American culture, at least in the way that I learned it from Fernando’s family. It’s arrogant to think that we can control everything. There are mysteries. And the different characters in the book have different relationships to the physical and the spiritual, the realistic and the magical, which also goes along with multiple voices creating and inhabiting a liminal space.

I think of these classifications in the same way that I think about genre: they are useful ways of thinking about what you’re writing and how you’re writing it—the craft—and knowledge of them can help you become more deliberate as your intentions evolve. They are artificial, yes, but they are something to use and something to push against. They are useful in marketing and in getting your work into readers’ hands, but unfortunately, they can be used to limit and to judge. In other words, I believe in using them to expand your possibilities.

I’m curious about the book’s subtitle, “A cycle of rather dark tales.” Throughout my reading of the book, I never would’ve called it dark.

I wanted the subtitle and the little blurbs under the title of each tale to serve the same purpose. I was trying to teach the reader how to read the book. I wanted to set up their expectations: because they are a cycle of tales, don’t expect a novel or a continuous narrative! I even included the definition of “tale” for that reason because it set forth all of the things these “tales” do: some might be fantastic; some, like gossip; some, true; some, an “accounting.” I used the epigraph from Candide and the subtitle to suggest that while the tales are going to dive into dark subject matter, they will do so with humor: they are only “rather” dark. With the little blurbs under the title of each tale, I was trying to say, “If you’re reading for what happens, sorry. That’s not what matters.” I was also imitating Voltaire, of course, and wanted to suggest that this book, like Candide, was interested in larger philosophical and political questions. I am glad that the cycle as a whole struck you as “light.” I guess it goes to my belief that if, in the middle of darkness, we do what we can for others, then at least some of the darkness will dissipate. Love is all we have?

What’s next for you with writing? Any possibility of a sequel to Jillian?

I would love to write more Jillian stories—I miss the characters. It was mostly a lot of fun to write them, but there is a way in which I like for each project to be very different from the one before. This goes to my being two people! There was a point at which I realized I would probably never make money from my writing and, say that was true, then why do it? And the answer was to amuse myself, to challenge myself, to see what I could learn. Also, I find you don’t have much control over your obsessions. Right now, in the middle of this pandemic, while waiting to see what the outcome of the election will be, I’ve found myself trying to write lyrical essays about travel I’ve done and the art and literature of those places—but the last one I wrote, on Barcelona, became pre-occupied with the Spanish Civil War and the following forty years of fascist rule. Like everyone, I find myself in an unsettling state of suspense.

I was going to ask you if you have any advice for younger writers just starting out, but I think what you just said above is such great advice. What if we are never able to make money from our writing, would we still do it? And why? If each young writer can answer that question for themselves, they can better navigate the waters of self-doubt, which are inevitable in this field. Any final wisdom for those just starting out?

I would say to aspiring writers, read, and find other writers you can share work with. The most important thing, maybe, is to cultivate an open mind and to learn to listen deeply to others, the way they say things as well as what they say. Not only will this help you write dialogue and make you more aware of the qualities of voice, but it will help you cultivate empathy. And go outside your circle of friends and family. Travel if you can, even if only to another part of town. Be patient with yourself. You might have very high expectations of your work, which is fine, but notice your strengths and develop them. The rest will follow, I think. Celebrate every breakthrough.