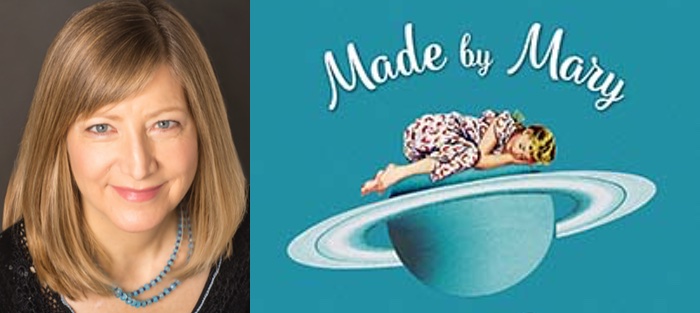

My interview with Laura took place at Word Bookstore in Brooklyn at the launch of her second novel, Made by Mary (C&R Press, 2018), which tells the story of a fraught surrogacy and the two women it brings together, Mary and Ann.

I had the pleasure of reading an early draft of the novel and found it to be a wise, funny, and poignant exploration of the complex ties of family. Laura in turn has become one of my most valuable and thoughtful readers for new work, plus a very dear friend for ten-plus years now. We talk about literature and craft all the time, so this conversation was a natural extension.

I didn’t show her the questions beforehand—I thought surprising her would make the interview more compelling, both for us and for our audience.

Interview:

Hillary Jordan: You know, almost all literature begins with a question or questions in the author’s mind, something we’re curious about and want to know more about, or something we want to imagine more fully. So, I would ask: What were the questions that made you want to write Made By Mary? And what were the biggest obstacles, if any, in answering these questions?

Laura Catherine Brown: The questions I had were about childbearing and motherhood. At a certain point in a woman’s life she switches from trying not to get pregnant to maybe wanting to get pregnant. Then it’s a question of how bad does she want to get pregnant? Will it happen? Won’t it happen? If it doesn’t happen, what transpires from that? What do you make of your life? I was living those questions. I realize this only in retrospect. Everyone in the book is me. There’s magical thinking, denial, anger, fear, and just a lot of stuff I was going through around the question of bearing children.

The character of Mary is at the heart of the book. She’s a mother who’s complex and imperfect and selfish and not always likable. In other words, a woman who’s fully human. It seems to me there’s a lot of pushback both in the literary world and in the real world against strong, flawed women who have powerful desires and agency. So, my questions are: Why do you think that is? Who’s doing the pushing? And was this book a response to that?

The character of Mary is at the heart of the book. She’s a mother who’s complex and imperfect and selfish and not always likable. In other words, a woman who’s fully human. It seems to me there’s a lot of pushback both in the literary world and in the real world against strong, flawed women who have powerful desires and agency. So, my questions are: Why do you think that is? Who’s doing the pushing? And was this book a response to that?

Mary was the first character who came to me. She’s an amalgam of women in my life. I think the pushback against so-called unlikeable characters comes from everywhere and it’s also internalized. Ann, the daughter, has formed her life in opposition to Mary. Ann is quiet, controlled and buttoned up. In a way, she’s going to live less fully than her mother. But even though Mary is driven by her narcissistic need, she still commits a loving, generous act that stands on its own, independent of the flawed impulse. That was one of the things I was exploring: the consequence and resonance of an action, as well as the warped way in which it arises.

It’s interesting because my thinking and my question were both more political and you’re going back towards the personal, which is kind of what the book does. The other corollary question is that you describe Mary as being “not pretty” and “middle-aged.” It seems that through her character you were making a statement about the invisibility of women like her and pushing back against that. Because you and I are older than Mary, and one does start to feel invisible. I wondered if that was also a part of your intention or just something that came out.

I think my life is filled with powerful complicated women. I really like writing them. Politically, this book takes place at the turn of the century, the year 2000, the millennium when everything was going to fall apart because computers hadn’t been programmed past 1999 and the power grid was going to explode, and the markets would crash, and everything would malfunction. But none of that actually happened. So, I think of it as a historical novel—last century! Politics are slightly different now than they were then, in terms of the backlash against feminism or women’s equality. Maybe the backlash has always present and is finally now becoming transparent and undeniable. Maybe we were just pretending to be liberated back then, or the media and the marketplace had successfully co-opted the women’s movement, making it a consumer product. So, I was really thinking of how you form a life within the limitations imposed on you by society.

Mary came of age in the ’60s. She ran away from home to hang out in Haight Ashbury and was heading to the Woodstock concert in a van with all her friends when she went into labor with her daughter. She grew up at a time when there was an opening and a mass movement against societal strictures and oppression. There was a burgeoning. Mary is still living that era in her head, she’s still there. Ann grew up in an opposite era. There would have been Reagan and Clinton, and the terrible election in 2000, you know, just a time of oppression and repression. And she has formed a personality around that.

On that subject: you use “burgeoning.” But it seems to me that one of the main themes of this book is expansion through pain. You have Ann with this tiny vagina that has to be stretched. You have Mary’s growing belly and incapacity. There’s a physical aspect and there’s a spiritual aspect. Ann grows tremendously spiritually, there’s an expansion of Ann and Mary’s relationship, of their understanding of each other, and the mother-daughter bond expanding. Is that something that you were trying to talk about, this idea of growth through pain? Is it your personal experience?

I think growth is usually painful. But I also very much wanted to write the experience of being embodied, navigating existence in a woman’s body. As women, we often take an outside look at ourselves, a very critical look at how we fall short. Mary doesn’t like how she looks. She’s heavy and she’s domineering. She has a loud voice and she knows this about herself, she can’t help it. She’s also very, you know, embodied. She sweats. She aches. She bloats. She has a lot of great sex.

Ann is embodied in a different way. She was born without a uterus. This is a congenital disorder called Meyer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome, MRKH. This occurs during the fetal development of the reproductive system and effects approximately one out of 6,000 newborn girls. The uterus and cervix are undeveloped or absent. But they have ovaries and normal development otherwise. So, there is a population of women who question whether they’re women because they don’t have all the parts. It brings up the question of what makes a woman? If you’re not a mother or you can’t birth a child, are you a woman? Who decides what defines a woman’s life? I was thinking along those lines. There is another character Ann’s friend, Cassidy, who’s irresponsible. She has kids even if she’s not great at taking care of them.

Yes, she’s effortlessly childbearing.

She hasn’t even named her most recent baby who’s a couple of months old because she can’t decide on a name. So, there’s that aspect too, of the people who can and maybe shouldn’t; and the people who can’t but should. Everyone wants what they can’t have.

The men in the book are kind of ancillary. It’s really Mary’s story and Ann’s story. It’s shifting third-person limited point of view. Joel has only a few sections and I wondered why you chose to inhabit him, what you needed from that, or why you did that, as opposed to just sticking with Mary and Ann?

I think I needed to inhabit Joel precisely because the men are ancillary to the main story. Historically, it seems to me, in a lot of fiction, especially fiction I studied in school, it’s the women who are ancillary. So, in a weird way I was flipping the script. The husbands and boyfriends are the sperm donators and support staff, and they’re feeling their marginality. I needed to inhabit Joel because I didn’t really know him. He also has a rather overbearing mother and a father who abandoned the family during the Woodstock concert, so Joel is also emotionally wounded. It’s not just women who are injured in this patriarchal society. It’s everybody. And I did want to inhabit his pain.

He’s very sympathetic despite certain actions he takes. He’s a sympathetic man, unlike Mary’s boyfriend, Peter, the British photographer.

Peter has nothing to do with my British husband!

Lots of your main characters take unexpected turns. Did you experience any of that yourself, when you were writing this book? Did the story go somewhere unexpected and were the characters changed in ways that you hadn’t anticipated?

I didn’t know that it was going end the way it ended. I’m not going to spoil it by saying how it ends, but the ending surprised me. Once I knew it, the ending seemed inevitable. But I didn’t discover it until very far into the process. And there was pushback against it by some parties because it’s not necessarily happy.

One of the other questions I had in regard to the unexpected turns, was about the magical realism. You crossed that line! I thought, “Wow she’s really going there.” Sparks were shooting out of this woman’s finger, right? So why did you do that?

The characters were always going to be modern-day Pagans or Wiccans. I personally know intelligent, thinking people who are practicing, ritual-performing Wiccans. So, I was very curious about it. At first my curiosity was skeptical and maybe mocking. I couldn’t take it seriously. I can’t take any religion seriously. It’s all make-believe. I grew up Catholic, so the Wiccan practice is not dissimilar in the rituals, the incense, the recitations and invocations. Wicca is just a newer, more recently-invented thing.

Some might say it’s an older faith.

Yes! It is older. The paganism was always present in the story. And at some point in the writing I realized that the religion can’t just be a background. It was already like a character, so Wicca had to manifest in some narrative way, more than just backdrop.

I found it fascinating because that’s where Ann comes into herself. She has always been really skeptical about it. Yet, that becomes the source of her power. She’s going to be the next high priestess, right? A lot of this stuff seems comic, you know. In the ritual scene, there’s the rainstick and the rattling gourds and then suddenly, wow, this shit works! It works.

I do think there’s power in ritual. It doesn’t matter if you believe it. The actions themselves can be powerful. And I discovered this, I think, through yoga, which people who know me, know I’ve been teaching and practicing yoga for 30 years. Just the doing: the practice, the ritual, the conjuring, this actually creates an energy that transcends normal mundane life. And I did aim to do that with Wicca. I wanted to give Ann, who’s completely in opposition to her mother, a journey that takes her from knowing her mother only as a mother, an all-powerful mythological figure, to knowing her mother as a woman. So, in the end, two women know each other and love each other without all the projections. I feel lucky to have come to that place with my own mother. She’s not Mary at all! For both my books the first thing my mother will say when you meet her, is, “Hi I’m not the mother.”

There was one passage where a bell went off in my head when I read it: Ann and Mary are riding in a car.

Yes! One of the things you said to me when you read an earlier draft, which I’ve never forgotten is: They’re always riding in cars to and from someplace. Just put them where they need to go. Get them out of the cars. And I went through the scenes and saw how right you were. That was a lot of extra narrative baggage.

But this particular car ride had to be kept. This one is great. Mary’s looking at the leaves turning color and reflects that they appear more vibrant and alive in their demise than they did in their prime. Without giving too much away, talk about that a bit.

I think it’s true that when the leaves are changing, they are more vibrant as they’re dying. And I feel there’s a metaphor about time truncating as you age. There’s less time, so every moment becomes much more important and meaningful. That’s where I was coming from. I did try to use the seasons throughout the novel, because the Wiccans abide and worship according to the seasons. I wanted to portray the fall, the winter, the spring, the summer, and the constant cycle of seasons.

So, I just want to ask one question about process because I always find process really interesting. With my books, I typically start with a character with a problem. Is there any method to your madness, or any sort of thing that you do when you’re beginning?

I think I start with a character, too. When my first novel came out, all those years ago, everyone said, “So what are you working on now?” I had nothing. I hadn’t even thought about what next, except for a vague idea about a mother-daughter surrogacy because I’d read about it in a newspaper article. “Grandmother Is Mother Until Birth,” I think was the headline. And I thought, that’s intense. I imagined, what if it was me and my mother and my husband, what would that be like? I really wanted to get into the dynamics: whose needs and desires and agendas were being played out? But I didn’t have a story. I had these characters. And I’ve told this sad tale a few times about the process—that it took me about five years to realize, after a lot of drafts, that I didn’t have a story. Then it took me another five years to get over the fact that it had taken me five years to realize I didn’t have a story! So, the novel took a really long time to write.

Then the journey to publishing was also long. At a certain point someone advised me to put the novel aside. It was hard to hear, but also a relief. It had been a couple of years of trying to get it published. A lot of writers have probably had this experience of endlessly submitting. So, I put it aside and wrote another novel about a frustrated visual artist who has to work in a bank and gets involved with a hedge fund manager who buys her artwork. But he’s crazy and he’s running a scam. I’ve written a couple of drafts, which feels good. If someone asks me what I’m working on next, I’ve got something! I’ve put that one aside for a few months now, so I can focus on bringing Made By Mary into the world.

Mary has needs!

Mary’s needs must be met!