Adam Rapp has been steadily writing for more than twenty years. While amassing over two dozen produced plays for theater—not to mention garnering a Pulitzer Prize nomination for Red Light Winter along the way—he has also written eight young adult novels, including the acclaimed Punkzilla (Candelwick, 2009), and a previous adult novel, The Year Of Endless Sorrows (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007). He is the recipient of the Benjamin H. Danks Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and when he’s not writing fiction or working on new plays, he’s writing for film and television. In short, when Adam’s not writing, the man is writing.

Bound up in Rapp’s writing is a focus on and fascination with music, which provides texture to many of the author’s erudite odysseys. So perhaps it should be likewise said that when he’s not writing about or referencing music, he’s playing music. Rapp is one fifth of Less The Band, a group of colleagues he’s worked with on plays and various multimedia projects for some time. In fact, one of Rapp’s earlier plays, Finer Noble Gases, featured the other four members of Less, and as Springsteen famously once said, you can’t break the ties that bind.

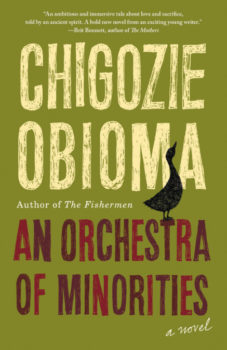

Know Your Beholder, recently published by Little, Brown, is dedicated to Mr. Rapp’s bandmates. And inside these pages lives a band very similar to Less, with mid-thirties Francis Falbo, the main character, against all odds (I promise I’m not trying to make cheeky music references here) trying to get on with his life after the band has broken up, leaving him dealing with his limitations in the face of adversity, and battling agoraphobia while living in the attic of his childhood home. “This morning the molten plates of my personal history took a tectonic shift when I realized it’s been nine days since I’ve removed the bathrobe,” Francis admits, no longer qualified to distinguish household or personal odors.

Francis has a healthy dose of performance anxiety, and one could argue the biggest stage beckoning him is life itself. The vestiges we wear underneath such tender skin get buried by time. When Francis speaks to what’s important, he clings to those traces of his former self while struggling with reality—how his mother’s passing still lives inside of him, how his bandmates (now no longer in communication) were once his best friends and the closest semblance to a family, and how his ex-wife’s love still owns him like a chest tattoo. “As I sit here in my yellowing, decade-old thermal,” Francis muses, transcribing his thoughts into a manuscript, “while the ghostly snow (it has officially been declared a blizzard) passes through the spill of weak moonlight outside my attic window, I am seized by the certainty that I am still obsessed with a woman who no longer wants me, and has not wanted me for a good long time.”

With no one to reach out to and little desire to go past his front porch, Francis finds himself in the middle of a crippling paradox, with new tenants arriving to live in each floor and room of his childhood home. So begins this new novel.

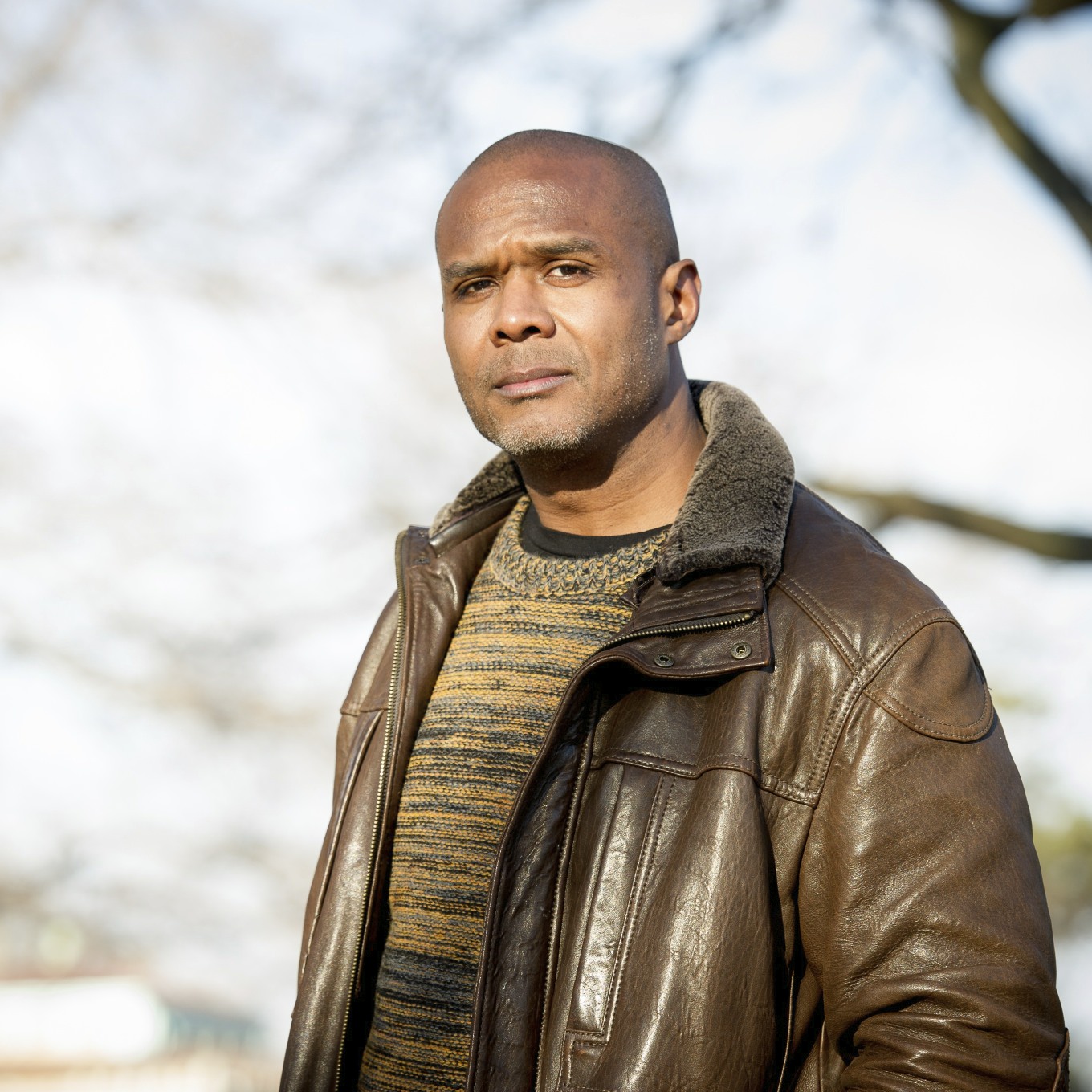

Five years ago, I had the opportunity to sit down with Rapp to discuss the release of Punkzilla for FWR. So it was a pleasure to meet him again to discuss this newest novel. We met on the book’s release date, and he was in the process of working on a forthcoming HBO show surrounding the Seventies New York music scene. If that’s not intimidating enough, he admitted he recently burned through multiple sixteen-hour writing binges to submit his latest YA novel. Just another average day for Adam Rapp.

Interview:

Brian Bartels: Know Your Beholder is set in Pollard, Illinois. A fictional place, but familiar in its Midwestern texture. Can you talk about how the Midwest has been a steadfast tableau in your stories and settings?

Adam Rapp: I spent my entire youth there.The long winters, tornadoes, mosquitoes, haunting twilights, and overall unpredictable weather, it’s all…bizarre, you know? It’s Apocalyptic there. Growing up, I felt there was this Russian sense of You Will Never Get Out. And those who got out had an epic escape planned. But I had an alternative adolescence. And I clutched this urge to get out.

Don’t get me wrong. There are lovely, beautiful things about the Midwest. In fact, when I go back now, time seems to slow down, and I’m still fourteen years old.

I read a terrific Aimee Bender comment recently: “Everything a human experiences happens on the body. That’s enough setting for me.” Where Beholder is concerned, Francis Falbo inhabits a multiplicity of settings in and around himself. Did you set out with these emotional and physical obstacles, or did Francis organically attribute his idiosyncrasies?

I read a terrific Aimee Bender comment recently: “Everything a human experiences happens on the body. That’s enough setting for me.” Where Beholder is concerned, Francis Falbo inhabits a multiplicity of settings in and around himself. Did you set out with these emotional and physical obstacles, or did Francis organically attribute his idiosyncrasies?

I’m obsessed with how we, as animals, morph and change and, you know, lose hair, and how we acquire molds, skin rashes, and foot funguses. We’re these petri dishes of imperfection walking around, and yet we’re fascinated by it all. Fascinated by death, waste, nutrition. You name it. Sometimes I look at my hand and I think, How did my hand become this way? Baffling and engaging.

Throughout the story we are reminded of an ongoing investigation surrounding a missing girl. Does the missing girl or loss of adolescence serve as a reminder of his own childhood for Francis?

It was a loss of innocence, or boyishness, sure. It’s funny. Part of being in a band is, you get to play. You get to be a child. And for Francis, and losing his band, I think he’s mourning that, and the missing girl offers a retreat for him. This hole of youth is closing in on him, so he wanted to preserve that.

What kind of kid were you, and do you feel that’s shaped your writing in any way?

I was a punk. I was quiet. I was angry. I was a total weirdo. If there was a group of people in a room, or relatives were visiting, whatever, I was always the one watching; a passive observer. I didn’t have many friends. And I was a jock. Sports helped, I think, because I didn’t have to communicate in a social way. Eventually, I had to communicate. I actually think sports have helped me be a better theater director.

I was small in high school. I had a terrifying fear of the dark until I was fifteen. I didn’t go through puberty until I was sixteen. I was this strange kid on trains and buses, always commuting, in military school. I got into a fight with my roommate my first day of military school. My mom didn’t know what to do with me. Thankfully, once I reached college I found writing as a terrific way of communicating all that.

Speaking of communication, instead of seeking therapy, Francis writes this manuscript and takes various substances. Did you always see him as finding therapy through writing his thoughts?

I have to always have a very strong justification for why a story will be a book. With Francis writing the manuscript, I felt if he had a strong reason to write it, it’s only sensible the reader would have a strong reason to read it. Other than The Sopranos, one of the most boring things I’ve ever watched is people in therapy, because they’re always processing their emotions. I felt the book would be dissatisfying if it was all therapy sessions. If there are two people in a room, I prefer them wanting anything other than the immediacy of therapy.

Though Francis has plenty of family drama to contend with, it seems the unresolved band drama continues to weigh the heaviest on him at times, along with his ex-wife’s absence. It applies a new perspective on family as it pertains to non-blood relatives. As the book is dedicated to Less, what are your thoughts on Band As Family?

I’ve never been more influenced by others than with my band. We’re all moving around, all over the country sometimes, but we actually have a show coming up, and plan on getting back together. Whenever we get back together, it still feels like we’re in seventh grade again. We’re the clowns with donkey ears. And there’s nothing like playing music with those guys. So writing the book was almost an elegy to us, even though we’re just in hibernation.

The only notable literary character I can think of who has agoraphobia might be Boo Radley. How did you come up with Francis?

Actually, my mom’s neighbor during childhood had it. Interestingly enough, she overcame her agoraphobia by becoming the woman who traveled around with the BookMobile, driving it around and parking it in our neighborhood, and that’s how she started beating her phobia. A lot of it was informed by that—that and forcing myself to think about ways to stay inside. It was a challenge, because you’re dealing with a static character.

Did that affect the way you though about space?

I apply similar rules between theater and fiction writing. Scenes should be about tension; what characters want and how they’re going to get it. Actors are often detectives. The goal is reaching an octave. I’ve never slowed time down much in novel writing. I like the challenge in that, in playing with time. Joyce does it well. I find if people are sitting there’s less tension. If there’s a way to get people to stand I’ll almost always try and do that. Asking questions about exits and entrances and trying to keep people in rooms is the ultimate goal. With Beholder, I was very meticulous about eliminating any forced scenes. It always needs to feel natural. My editor really helped in getting me out of longer scenes.

I apply similar rules between theater and fiction writing. Scenes should be about tension; what characters want and how they’re going to get it. Actors are often detectives. The goal is reaching an octave. I’ve never slowed time down much in novel writing. I like the challenge in that, in playing with time. Joyce does it well. I find if people are sitting there’s less tension. If there’s a way to get people to stand I’ll almost always try and do that. Asking questions about exits and entrances and trying to keep people in rooms is the ultimate goal. With Beholder, I was very meticulous about eliminating any forced scenes. It always needs to feel natural. My editor really helped in getting me out of longer scenes.

Let’s move from space to objects. Francis believes inanimate objects burrow his consciousness. A cactus knows he broke into his tenant’s apartment. A humidifier and microwave are in cahoots. Can you talk about how these objects made their way into the story?

When you’re spending a lot of time as writer, you’re alone in a room. So objects become your attendants. Can openers. Alarm clocks. I think it becomes very easy to embroider what they’re thinking, and soon they become more than just objects. I’ve always found there’s more reality to the most mundane objects.

There is a terrific passage on pages 334-335, where Francis categorizes humanity into two parts. Life A reflects a polite, expectant, morally sound person. Life B inhabits the depraved, carnivorous, lustful and possibly even homicidal self. Arguably, this reflects the Good vs. Bad in all of us. Were you tethered to that philosophy as Francis survived his ups and downs?

The Raskolnikov influence [from Crime and Punishment] was instrumental. Here’s this character, this student, living hand-to-mouth in a little dorm, barely has a jacket, and then when he murders the pawnbroker and her sister, he’s tainted his soul forever. And throughout it all, he seemed like a normal kid—and he probably was a normal kid—but through one large or small moment, we can change our lives. What Dostoyevsky does is a fantastic moment in character writing. He doesn’t telegraph the act. But then it absolutely defines him for the rest of his life. There are moments where Francis is on the precipice of losing so much more than he realizes, then steps off the ledge. I feel there are moments in our life where we make the wrong choice, or we make The Choice, and the consequences can be harrowing. I think we get those choices every seven or so years, and hopefully we get to create our own narrative.

You studied writing in college, right? Is there a method or practice you learned early on which resonates today?

I did, yeah. Clarke College. One professor taught an automatic writing exercise where you just start writing and keep going. And I still do that today. I think it really helps me get in touch with my unconscious. When I’m writing I’m in that mode all the time. Later, I go back and clean up. With a book, I’ll start from the beginning, which is helpful for my editing process. Everyone is different. I’m told Delillo has an interesting method of writing the first draft on a manual typewriter, then re-typing the second draft by putting each individual paragraph on a separate page, so he has this towering stack of a second draft. Meticulous edits. Then he has another go at it, and that next draft is the script that gets transmitted. Mind-blowing.

Can you read other fiction while working on the large novel format?

I do. I love reading other people while writing. I love it. I read A Visit From The Good Squad recently, and I fucking love that book.

Have you ever taught fiction? Or do you have general advice for a writer working on a novel?

I did. I taught at Vermont College. Young Adult fiction. Loved it. And I also taught playwriting at Yale and Wesleyan for a year each. I love talking about plays and books, my own struggles with writing, and helping young writers figure out their voices. It’s so important. John Guare and A.R. Gurney have always been incredibly generous to me, so I want to give back in any way I can.

Future fiction: what’s a story you’d still like to tell?

I just submitted a YA book called Fum, about a giant girl who’s, well, a giant. She has these visions. And her community turns against her.

Beholder does such a remarkable job exploiting our phobias and anxieties, I wanted to submit a last-minute anxiety test if you’d like to participate?

Sure!

SPEED ROUND Random Anxiety Test for Adam Rapp: which causes you more anxiety?

- Inertia or movement? Inertia.

- Opening night of previews or first time playing a new song? Previews.

- Getting your photo taken or getting asked to take a meaningful photo of strangers? Getting my photo taken.

- Habitual murmuring or high-pitched voices? High-pitched voices.

- Modeling nude or being mummified in string? Modeling nude.

- Tinkling piano keys in the distance, or nearby slowly eeking violin? Piano keys, definitely.

- Lines to the bathroom or lines at the airport security checkpoint? Lines to bathroom.

- Bad breath or bad B.O.? Bad breath.

- NYC Taxis laying on their horns or running into the fuckers who bike silently through the city streets? The fucking silent bikes. Someone’s going to get hurt.

- Woody Allen 1977 or modern day composite Woody Allen? Modern day Allen.