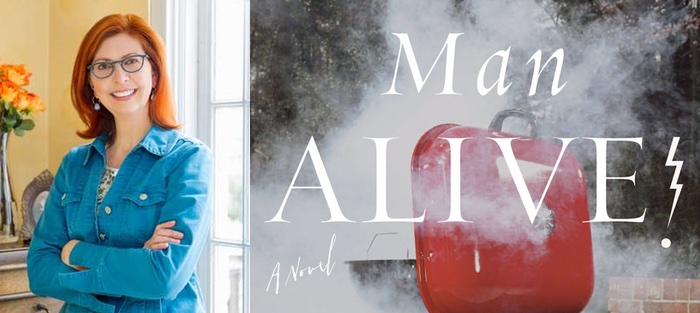

If the D.C. literary scene had a patron saint, Mary Kay Zuravleff would be anointed. She is beloved in this community as a writer, a teacher, a nourisher of fellow authors, and a devoted member of the arts. In the fall of 2013, another icon of D.C. literature, Politics & Prose, hosted the book launch for Man Alive! (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). Almost one hundred people, including myself, packed the small room to celebrate the book’s success and to listen to her wisdom. At the after party, hosted by another D.C. literary legend, Margaret Talbot, Mary Kay shared the journey of her novel while guests feasted on barbecue, a staple of her story.

Man Alive! illuminates the randomness of the everyday and the struggle in every family to love what we know and accept what we can’t. In the book’s opening scene, Owen Lerner is struck by lightning while feeding a parking meter on the final day of his family’s beach vacation. He survives but little in his life is the same. As his family unravels, Owen must recalibrate and recommit to the reality he once helped construct.

Mary Kay cofounded D.C. Women Writers, which meets monthly to network and support literary careers. She serves on the board of the PEN/Faulkner Foundation and co-curates the PEN/Faulkner Reading Series. Mary Kay has taught writing at American University, Johns Hopkins University, and George Mason University. She’s won the American Academy’s Rosenthal Award, the James Jones First Novel Award, a 2015 D.C. Individual Artist Grant, and was nominated for the Women’s Prize in Fiction. Man Alive! is her third novel.

On a recent rainy December day in D.C., Mary Kay and I met up for tea at Politics & Prose following the paperback release of Man Alive! In the cozy basement café, we talked about the community we share and what it means to be a good literary citizen.

Interview:

Melissa Scholes Young: One of your previous novels, The Frequency of Souls (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1996), was also about electricity. What was the path that led you to Man Alive!?

Mary Kay Zuravleff: I’m obsessed with electricity. My father and brother are electrical engineers, and though I started college with that major, I find electricity more mysterious than explicable. A few years ago, I read a New Yorker article, “A Bolt from the Blue,” by Oliver Sacks, about an orthopedic surgeon struck by lightning who suddenly heard music in his head. That guy left his family and learned piano and composition so he could transcribe what he heard. That was interesting to me, because I often described my own writing journey as trying to get the music I heard in my head onto the page. My imagination was faster and the stories stranger than I could capture. I didn’t have the writing chops until I finished my first novel. So that’s why the Sacks article spoke to me at first. Then, one day, I was sitting in my studio at VCCA [Virginia Center for the Creative Arts], and it was time to start a new book, and I thought: a pediatric psychopharmacologist is struck by lightning and all he wants to do is barbecue. There’s the story.

Man Alive! is so many stories and interweaving themes: extramarital affairs, abusive relationships, suburban life, consumer culture, and modern families, just to name a few. There’s also the paradox of medicating kids while simultaneously policing recreational teen drug use. Your main character, Owen, who is struck by lightning, is called out by his daughter for hypocrisy because he prescribes medicine to his pediatric patients but also advocates for a clean, healthy diet.

That part of Owen is one of the modern paradoxes we live with. It’s incredibly essential for many of his patients to be medicated to function normally. They require pharmaceutical intervention to behave “normally.” For Owen, what’s “normal” is blown up by the lightning strike. And, in fact, the entire novel is about what we establish as normal.

The world is constantly throwing you a curve. So who is to say what’s a “normal” family? What’s a “normal” marriage? What’s a “normal” way of being?

After Owen is struck by lightning, he becomes obsessed with barbecue. What is that about?

I like barbecue. But for Owen, it plays out as another battle between the natural and altered worlds. He’s blown back to his primitive self: fire, meat, and following his desires. But doing that in our time means googling what kind of wood burns hottest and making a dotted line on his screen to show what cut of buffalo steak he wants delivered to the house. That’s how Owen returns to his primal roots.

But some of those roots also tangle. You write about the overwhelming obligations to the mundane in a family. Even Owen’s wife, Toni, feels this ambiguity as caregiver during his recovery. The caregiver is supposed to be cheerful, selfless, and willing. I love that Toni isn’t. She’s an honest portrayal of what it means to be this deep in tragedy with someone you love who has profoundly changed. Toni is supposed to take care of Owen, but the Owen she depended on and knew before is fundamentally shifted because of the lightning strike.

It’s refreshing to hear that. I visit a lot of book groups and the response to Toni goes both ways. About half find her cold. They think Toni is a whiner. They want her to play the hand she’s been dealt. I see Toni as pragmatic, straightforward, and funny. One of the most touching compliments I received was from a reader who said, “Your love for your characters was so evident that even when they came on dark times, that care held them until they regrouped as a family.”

How do you manage your readers’ reactions at the book clubs?

How do you manage your readers’ reactions at the book clubs?

I just listen and I reinforce that their reading is their reading. Everyone’s experience is unique. It’s real to them even if it’s not what I intended.

During your book launch, you shared with the audience that you originally wrote Man Alive! in past tense but revised the entire manuscript in present tense. What does present do that past can’t?

The novel was supposed to be done, and as I was rereading it in past tense, I realized it was too slow. The problem was pacing. The visualization I had in my head was that the family was arranged like billiard balls on a pool table and the lightning strike hits cue-ball Owen, which in turn scatters them in all directions. The reader is supposed to feel like she is just holding on for the ride; in past tense, that urgency was lost. First, I trimmed language, the flowing, surreal account of what Owen felt and imagined in his scrambled brain. But that made it too truncated, too staccato. I realized that the problem was tense. If I wanted the reader in the fire with Owen, present is the more empathetic tense. Usually, present tense slows things down because it takes so long to get anywhere, right? Past tense is one of elision. You can really travel in past tense. But for Man Alive! I needed the reader to be right inside the flames.

We spend a lot of time in the flames of Owen’s head, then Will’s, before Toni jumps in and finally, Brooke and Ricky. It’s a very Virginia Woolf point of view shift. What was your goal?

I wanted the book to be told in what I was calling Family Point of View. We need to hear from everyone, because this happened to everyone. And I discovered in the writing of it how little we share one to another, no matter how close we are: they are each going through a completely different experience. I wrote many drafts before I figured out how to calibrate who narrates what.

These aren’t the kind of decisions I make easily in drafting, because I’m still figuring out the book. Each writerly decision contains the DNA of the novel: the first sentence, the tense, the point of view is essentially the whole book. Meanwhile, you don’t want the book to feel redundant. And so it’s a matter of calibration.

Is calibration how you teach the novel in your creative writing classes?

Mostly. I teach now at WriterHouse in Charlottesville. Eight writers come to the class with a full draft of their novel. At George Mason I taught a novel writing class in a semester; it was incredibly fast because you were generating so much content in so little time. Then students would spend years rewriting. This WriterHouse class requires students to come in with a complete draft of a novel.

What do you consider a full draft?

A beginning, middle, and end. Then we’re critiquing and we can really go deep. They have the story so I can ask, “What is the emotional core of this story?” and “What about the choices you’re making in tense?” and “Who is the main character in this draft?” You know what’s it’s like, Melissa. You’ve finished a novel. How many drafts did it take before you knew the story?

Six full drafts.

And when did you know the story? At the end of the first draft?

I tend to follow Mark Twain’s advice: “The time to begin writing a [novel] is when you have finished it.”

See? Isn’t that amazing? When you’re teaching and you say that, it can paralyze a writer. But the getting of the story on paper reveals the real story. We also read books on craft.

What craft books do you recommend?

I have practically memorized Annie Dillard’s The Writing Life, and in my latest class we’re enjoying How Not to Write a Novel [by Howard Mittelmark and Sandra Newman, William Morrow, 2008].

Who are your other writing influences?

I’m always reading and berating myself for not reading more. I need to read War and Peace and reread Middlesex for what I’m working on, but then all these Best of 2014 lists have just come out, and there are a dozen new novels I want to start!

And speaking of writing advice, you wrote an essay for The Atlantic called “How to Make Your Book a Bestseller.” It’s tongue-in-cheek suggestions on taking your book to the top: sell yourself, get arrested, stalk readers, etc. Are you warning the overenthusiastic novelist? How is marketing your book today different from when you debuted?

You are expected to do so much more of the marketing work. It’s not enough to just write a great book; you have to be a part of what gets that book out in the world. The Atlantic essay was inspired by a newsletter from my agent’s office that essentially said we were responsible for making our own gravy.

How do you make your own gravy?

Say yes to everything. Offer to visit book clubs. Ask bookstores, the library, your college to host a reading. You don’t have to go solo; maybe you help organize a group reading or a panel. Ask your friends to host a book party and volunteer to have a book party or a dinner for other writers. Be your book’s best champion. Be a part of your literary community.

The D.C. literary community is so vibrant and supportive. You and I seem to cross paths often at PEN/Faulkner events, readings, D.C. Women Writers’ dinners, and through mutual friends. I’m amazed by the caliber and generosity from writers like you. Was it always so?

The D.C. literary community is so vibrant and supportive. You and I seem to cross paths often at PEN/Faulkner events, readings, D.C. Women Writers’ dinners, and through mutual friends. I’m amazed by the caliber and generosity from writers like you. Was it always so?

No. It took us years to find each other and cross-pollinate. There have always been inclusive people like Richard Peabody, who publishes Gargoyle magazine and many anthologies, and Susan Shreve, who helped start both PEN/Faulkner and George Mason’s MFA program. But the city has become as much a literary as a government town: good bookstores, journalists writing creative nonfiction and memoir, and so many novelists! I have seen a change of mood from bitter critics like Jonathan Yardley to critical enthusiasts like Ron Charles, just to use the Washington Post as an example.

In the introduction to Wendi Kaufman’s short story collection, Helen on 86th Street and Other Stories, posthumously published by Stillhouse Press, you write about the importance of work and service. Wendi seemed to live her life not only through the arts but also through her devotion to other writers. What does it mean to be a good literary citizen? And how does it help your book?

I love hearing an artist’s raw material—Shakespeare recited by pigs in graphic novel format was yesterday’s coffee conversation—and celebrating the final product. This has happily been deemed “good literary citizenship.” And so we egg each other on, listen, read each other’s drafts, and promote each other. That helps, because writing is solitary and novels take forever.

I feel about literature, imagination, and my friends the way my mother feels about church: it’s important to me and it’s personal. Other authors may not need/enjoy the community that I do. That said, I’m happy to help out in many causes that bring people of all ages to literature and imagination or bolster the community I treasure.

What are you working on now?

I write with a question. For Man Alive!, the question was, “How much can you change within a family, unless you don’t want to be in that family anymore?” The question for the next book, which somehow follows four generations of women starting in Russia and ending up in Washington, D.C., is “Should I stay or should I go?” But the music in my head has to do with the Old Believers of the Russian Orthodox Church, Oklahoma, and the representation of hyperbolic space through crocheting. We’ll see how that makes it to the page.

These questions often lead to dangerous answers, though. I understand that you have a knack for predicting your own future in your books.

Be careful what you invent, darling. The notion of imagination and intuition holding hands is powerful stuff. We could have an entire eerie discussion about what has come “true.” What I would say today is that it seems that in each book I have condensed what I know about the past and the future into a lucid dream.