Editor’s Note: As we approach our tenth year of publishing Fiction Writers Review, we’ve decided to curate a series of “From the Archives” posts that we’ll re-publish each week or so during 2017. Some of these features are editor favorites, some tie in with a new book out from an author whose worked we’ve covered in the past, and some are first conversations with debut authors who are now household names.

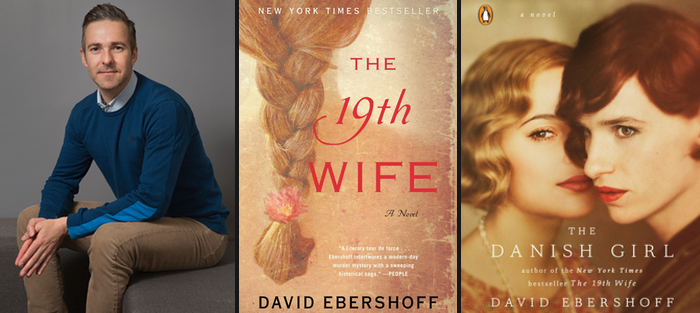

This week we’ve returned to Brian Bartels’s interview with David Ebershoff, which was originally published on September 6 of 2010. Ebershoff’s 2000 novel, The Danish Girl, was adapted into the oscar-winning film starring Alicia Vikanderand and Eddie Redmayne, and his 2008 novel, The 19th Wife, was adapted into a television movie. He’s also the author of the novel Pasadena and the story collection The Rose City.

Brian Bartels, who is a long-time contributor for Fiction Writers Review, serves as the director of bar operations for Happy Cooking, which runs the West Village restaurants Jeffrey’s Grocery, Joseph Leonard, Fedora, Perla, and Bar Sardine. His first book, The Bloody Mary: The Lore and Legend of a Cocktail Classic, releases from Ten Speed Press later this month.

In John Steinbeck’s The Winter of Our Discontent, the author fictionalizes the old whaling community of Sag Harbor, New York, re-naming it New Baytown. Riffing on the city with tongue-in-cheek aplomb, its misanthropic, disillusioned narrator-protagonist describes the place, saying, “Porlock Street has kept its gas street lamps, only there are electric globes in them now. In the summer tourists come to see the architecture and what they call ‘the old-world charm’ of our town. Why does the charm have to be old-world?”

In many ways, it is the narrator’s attitude about the setting as much as his physical descriptions that creates our sense of the place. “If I wanted to make a picture of it for myself,” he continues, “it would be a wet sheet turning and flapping in a lovely wind and drying and sweetening the white.” And here is where fiction does its magic—filtered through the individual’s emotions and experiences, place is comprised not simply of sensory descriptions but also abstract emotions and images.

Yet what about imagined landscapes? Let alone historical ones? How does a writer go back in time to inhabit a past that lives and breathes beyond mere facts, that is tinged and tainted by an individual’s experience in that place?

One writer who has managed to accomplish this task exceptionally well is David Ebershoff. If there is such a thing as a “chronicler” of fiction, Ebershoff belongs in such prestigious company. He does not travel down easy roads—his work has been set in 1930s Europe, early-1900s California, and Utah during the mid-to-late 1800s—but his journeys pay off for us as readers. For Ebershoff has the ability to resuscitate these rough yet enchanting locales with chameleon-esque delicacies of identity. Likewise, his prose straddles the muscular and the mellifluous equally well. Characters transform in Ebershoff’s stories, shedding layers of external detritus for an expression of what’s inside. Ebershoff writes of these times in vivid, imaginative detail.

In The Danish Girl, Ebershoff connects our capacity to materialize dimensions by utilizing an activity such as painting to capture landscape, applying light to create color, shaping mood, fabric, and tone. We see the same tools applied in Pasadena, where rolling hills become long dirt roads lined with hottentot figs blooming with yellow flowers, and then become orange groves and bluffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean. With similar dexterity he captures the loneliness of highway roads in The 19th Wife, writing:

. . . past the crystal meth dens of Hurricane, there’s a long county highway to nowhere. It rises up, crossing an empty desert plateau with red mesas and stony mountains and stands of pinon in the distance. On the road there’s nothing for fifty miles except a gas station, a lunch counter, and a wire cross marking the site of a fatal crash. It’s got to be the loneliest road in America.

Yet beyond his ability to render history with staggering accuracy—both in terms of a particular place and era—one of my favorite aspects of Ebershoff’s writing is how deeply he inhabits the lives of his characters. And because of the precise attention he gives them in capturing their inner conflicts and struggles, we think about the people around us daily in a different way. We realize that the people who pass us by on a random street corner, somewhat indistinguishable, may quite possibly be the most interesting person we have yet to meet.

Recently, David Ebershoff was kind enough to take the time to answer some of my questions via email in the midst of the many other literary endeavors that keep him busy—writing, working as an editor-at-large for Random House, and teaching in Columbia’s MFA program. Not surprisingly, I found his world to be a whirling, captivating, and inspiring one, always working on story, and where, ultimately, it finds its shapes.

Interview:

Brian Bartels: What are some of your early memories of books, and how did they affect you?

David Ebershoff: Among the earliest is Ferdinand the Bull. I probably first encountered that book when I was three or four. The book has many messages, but the one I carried in my heart throughout my childhood was that there are big sissies in the world and they deserve our love. Later, at eight or nine, I read The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. That left me with the hopeful feeling that no matter where I was there would always be a door, often hidden, that could lead to a world far more magical than my own. At ten or eleven, I read Judy Blume, who revealed the connection between fiction and sex. That was the first time ink and paper lit a fire down there.

When did writing become your lighthouse?

In my teens, when I read some of what today we might call the 20th century’s gay canonical writers: EM Forster, Thomas Mann, James Baldwin, Truman Capote, Christopher Isherwood, Gertrude Stein, Edmund White, Andre Gide, Carson McCullers, Gore Vidal, Denton Welch, Joe Orton; and more recent gay writers like David Leavitt, Armistead Maupin, Andrew Holleran, Felice Picano, and Rita Mae Brown. When I was fourteen, fifteen, and sixteen I’m pretty sure I read every book in our local library with a gay character, and if I heard a writer was gay, or might be, I’d read him or her, too. Obviously I was searching for some sort of mirror in the page. I can’t tell you how disappointed I felt when I read a book by a writer I knew to be gay and discovered it had little to do with gay longing. I would turn red (pink?) with genuine outrage, as if my own sister had betrayed me—the kind of narrow, seething dismay only a teenager can summon.

What are some obstacles you faced early in your writing career?

Fear. I was afraid to write about what I really cared about. I was afraid to say what I believed. I was afraid no one would be interested in what I was interested. I remember when I first thought of writing about Lili Elbe [whose life was the inspiration for The Danish Girl]. I thought to myself, “Who would want to read about her?” Thankfully I answered the question boldly: I would. I wanted to read about her, that’s why I decided to write about her and her remarkable life.

Is character what first compels you to begin a story?

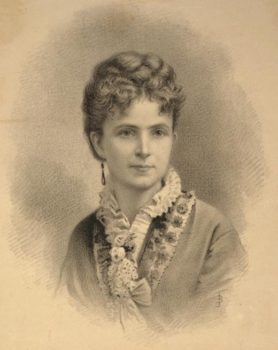

It comes from wondering. I remember when I first heard about Ann Eliza Young, the so-called 19th wife of Brigham Young, the second leader of the Mormon Church. I wondered what it would be like to share your husband with eighteen, or possibly more, other wives. I wondered what it would be like to be known as the 19th Wife—what a strange moniker soaring above one’s head. I didn’t know what kind of novel should house a woman like this, I just wondered what it was like to be her and to see the world through her eyes.

Because you often write about such specific individuals or moments in history, do you feel obligated to visit the places your stories exist or have existed? Do certain objects/landscapes help you establish your fictional dimensions?

Yes, I love walking where my characters have walked, or might have. It unleashes numerous ideas in my mind. The light, the trees, the color of the soil. For me it’s important to know where the sun sits in the sky at a particular location and the degree (or lack thereof) of its warmth. I don’t always need to tell my reader this, but it helps me understand my characters. In The 19th Wife, the physical isolation of Utah in the 19th century is important to the story. The only way to experience that as my characters did is to get out there in the dust and start walking around. The desert sun in July left its mark on my imagination’s hide.

Another example of this was my trip to the river-town of Nauvoo, Illinois, where Ann Eliza Young was born. Her father was a blacksmith there and his shop and her family home survives today. It’s a small cottage, maybe twenty feet by twelve. I knew that Ann Eliza’s father lived here when he married his second wife, that this was the home he brought his new, younger wife to. This means that on his wedding night to his second wife, his first wife, Ann Eliza’s mother, was only a few feet away. By seeing the cottage’s floor plan I could easily imagine Ann Eliza’s mother on the other side of a thin door while her husband consummated his second marriage. This became an important scene in the book and I could only write it because I put myself physically in the location.

Another example of this was my trip to the river-town of Nauvoo, Illinois, where Ann Eliza Young was born. Her father was a blacksmith there and his shop and her family home survives today. It’s a small cottage, maybe twenty feet by twelve. I knew that Ann Eliza’s father lived here when he married his second wife, that this was the home he brought his new, younger wife to. This means that on his wedding night to his second wife, his first wife, Ann Eliza’s mother, was only a few feet away. By seeing the cottage’s floor plan I could easily imagine Ann Eliza’s mother on the other side of a thin door while her husband consummated his second marriage. This became an important scene in the book and I could only write it because I put myself physically in the location.

So do you feel that setting is one of the most important aspects of good writing? Should authors strive to incorporate geography and topography into their work?

I don’t think so. It depends on the writer’s sensibility and the story at hand. Some stories don’t need much setting. Sometimes a sentence as simple as “We lived on a cul-de-sac north of Milwaukee” is enough to place the reader in the character’s world. Or imagine a book that opens: “Paris, dawn, fog on the Seine.” Does the reader need more? Probably not. I have no rules about setting and physical description except that it all should count.

I’m curious to know how the Church of Latter Day Saints reacted to The 19th Wife. Although the book is a work of fiction, did you receive any sort of response from the members about how you depicted their community?

One of my favorite aspects of Mormon culture is its reverence for the past and its commitment to documenting and preserving its history. Since the Church’s earliest days, its members have made great efforts to record and preserve their stories. This makes researching LDS history fairly easy and accessible. True, there are numerous documents unavailable to non-members, but there are plenty of sources available in the various open LDS museums, family history libraries, the Utah libraries, as well as online. Since the book was published, I’ve received hundreds of emails from Mormons. Many thank me for writing the book. Others tell me they did not know this about their own church history. Others write me with interesting anecdotes about polygamous ancestors. A few write with theories (mostly conspiratorial) about what happened to Ann Eliza Young (she disappeared in 1908). I’m often asked if I grew up LDS because I seem to have captured the culture in a credible way. That’s all because of the easy (and often free) access to LDS history. The Church has devoted impressive resources (time and dough) to making that history available.

I’ve received four or five emails from Mormons who took exception to the book. A couple of these have led to an interesting dialogue between the writer and myself. A couple were irrational and I had to ignore them. But I’m always grateful to hear from a reader. I try my best to respond to all my emails promptly, although this summer I’m behind on that because I’ve lost myself in my new book. As a writer, I perceive fictionalized history as a terrific device for not only the artist’s explored interest in perhaps a previously unfamiliar subject, but as an opportunity to dust convention.

Does fictionalizing history offer you a compelling alternative to what we may or may not believe?

You’re right. That is one of the compelling reasons to look back. It gives the writer an opportunity to re-examine an event or a person that most people believe have nothing new to reveal. Of course the writer achieves this, as you say, from his historical perch + personal point of view. My 21st-century perspective enables me to see the 1930s differently than anyone in the 1950s could have. This is inevitable. Shakespeare relied heavily on Plutarch to write about the Romans, but needless to say Shakespeare and his Renaissance worldview add much to our understanding of Caesar and Mark Antony. The inverse is true, as well. The past can reveal much about ourselves today. After 9/11, I wanted to write about faith and fundamentalism in America. I realized that the history of polygamy in the United States offered some indirect but useful examples of the complex intersection of religious freedom and personal freedom.

Which compels a sub-question. Your characters are apt to break rules. Does the writer in you believe a blank page offers the same conceit? As an instructor/professor of writing, what rules apply to your doctrine of craft?

There are no rules in fiction. Every story or novel can be whatever it needs to be. This is what makes fiction potentially radical, even now. Even so, every story or novel creates its own rules. Part of the task of writing is figuring out those rules and then applying them or purposefully defying them. Some rules are basic: if the novel has a first-person narrator, the “I” is your narrative engine (of course books like The Book of Daniel or We Were the Mulvaneys defy this very rule to powerful effect). Some rules are more subtle or unique: in The 19th Wife I wanted to write a historical novel with a contemporary murder mystery woven through it. I established a rule that in the contemporary story all action would move forward. Because the rest of the novel was looking back, I wanted this narrative thread to keep the reader shoving ahead. I knew this would improve the novel’s pacing, something I was concerned about because of all the historical detail in the book. I found this rule helpful and orienting, like a rope chained to the side of a mountain. I clung to it lightly and proceeded up the trail.

Because history plays such a large role in much of your work, I imagine that you had to conduct a fair amount of research. Every writer has a different approach when researching story? What’s yours?

To paraphrase Einstein, it wouldn’t be research if we knew what we were doing. After I completed The 19th Wife people often asked about my research process and I would tell them, in great summary, how I went about accumulating the details and understanding to write the book. In retrospect, when told in organized anecdote from the podium, it sounds like a process, but in truth there was no process, at least not until much later when, perhaps, the patterns in the carpet began to emerge. Research gives a sort of professional, even scientific sheen to my kind of inquiries, but more honest words would be gathering, sifting, sorting, querying. Sometimes I feel like a pig in the forest, my snout muddy in heavy pursuit of truffles. Sometimes I feel like the ghostly scholar, his spine permanently bent over his books. Sometimes I feel like a Hardy Boy dashing about the neighborhood two clues short of solving a crime. Sometimes I feel like the journalist skeptically interviewing authority. Sometimes I feel like the student dropping into his professor’s office hour to ask a very large, unanswerable question on the nature of everything. All of these activities begin to inform my perception of a character or an event or a social issue. In retrospect, I can tease a process out of them, but at the time perhaps the best word to describe what I’m doing is an effort. I’m making an effort to write a book.

To paraphrase Einstein, it wouldn’t be research if we knew what we were doing. After I completed The 19th Wife people often asked about my research process and I would tell them, in great summary, how I went about accumulating the details and understanding to write the book. In retrospect, when told in organized anecdote from the podium, it sounds like a process, but in truth there was no process, at least not until much later when, perhaps, the patterns in the carpet began to emerge. Research gives a sort of professional, even scientific sheen to my kind of inquiries, but more honest words would be gathering, sifting, sorting, querying. Sometimes I feel like a pig in the forest, my snout muddy in heavy pursuit of truffles. Sometimes I feel like the ghostly scholar, his spine permanently bent over his books. Sometimes I feel like a Hardy Boy dashing about the neighborhood two clues short of solving a crime. Sometimes I feel like the journalist skeptically interviewing authority. Sometimes I feel like the student dropping into his professor’s office hour to ask a very large, unanswerable question on the nature of everything. All of these activities begin to inform my perception of a character or an event or a social issue. In retrospect, I can tease a process out of them, but at the time perhaps the best word to describe what I’m doing is an effort. I’m making an effort to write a book.

How much ground do you typically try to cover on a first draft?

I’m a slow writer and I tend to revise as I go along. For me, a first draft, by the time it’s complete, is in many ways a third or fourth draft. If I’m a hundred pages into a novel and I realize my protagonist needs a brother, I’ll go back and insert him before moving ahead. I’m always fixing my prose before I move forward, both as an effort to get my words right and, I’ll admit, to procrastinate. Often I wish I could just sit down and, as they say, bang out a first draft, but every time I’ve tried the only banging has been my head against the desk.

As a writing teacher, is there any advice that you offer your students before they get too involved in a story?

I once heard Joyce Carol Oates describe it in the terms of filmmaking. She said a director doesn’t just take the cap off the lens, shout “Action!”, and begin filming. He or she will spend months and months, even years, in pre-production. That’s what Joyce says she does before she sits down to write a first draft: she takes notes, tests voices, works out her structure. (She writes about this in her published diaries, The Journal of Joyce Carol Oates, 1973-1982—a book that I recommend to any writer interested in learning the secrets of a productive artist.)

Another word for all this is planning. I advise my students to ask themselves big questions early: Who is telling the story? Who else could tell it? What is the most effective narrative structure? It’s no fun to get to the end of a draft in the first-person and realize it should be in the third-person. (I’m speaking only from experience.) Yet I remind my students that these are difficult questions to answer in the abstract. Through writing you’ll arrive at the answers, even if what you end up writing early on has no part in the narrative.

This is not the same as outlining, something people often ask me if I do. I don’t. Many writers (not all) need to spend time planning their books, yet this needs to be done in a way that leaves room for spontaneity and the magical connections that form unexpectedly in fiction.

As an accomplished editor, you’ve worked with many different writers, including Shirin Ebadi, Billy Collins, Charles Bock, Gary Shteyngart, and, in recent past, Mr. Norman Mailer. So I’m curious how your editorial skills have affected your own work.

I try to remind myself of certain principles. I tell myself to start boldly. Everyone loves a novel that starts so dramatically that it is basically daring the reader to stop. David Mitchell has talked about this and his novels always open vigorously. I tell myself to reach. Who wants to read a novel about a minor event? I remind myself that, with a few exceptions, most writing improves through revision. If I’m not happy with a passage or a scene, I know it can be fixed. (Of course cutting it altogether can be the fix.) And I try to remain professional. I’ve learned that, for the most part, the best writers in the world are highly professional. Norman Mailer made it a point of delivering a manuscript without a typo. He always liked to deliver a manuscript in person to shake my hand. He was an artist, but he also behaved professionally, which is another way of saying, treating everyone in the business with dignity and respect.

As an avid reader, what do you seek in your fictional escapes?

It depends on my mood and my other mental obligations. This spring, when I was teaching a fiction workshop, I needed to read something far away from my students’ work. I read Patricia Highsmith’s five Ripley novels. Although a murderer, Tom Ripley is a delightful companion. And that’s the core of Highsmith’s genius: she invites the reader to share a meal and a good red wine with a murderer—and we can’t refuse the invitation! Diabolical. If there were five more, I would read those, too. I would talk about Ripley and Highsmith in class, but I fear most MFA students hear murder and think of a supermarket paperback. I don’t know why that is. I’m certain these students read Macbeth when they were young. Shakespeare didn’t fear debasing his art with witches and blood. Yet some young writers today look down on genuine dramatic action. Recently I advised a student to stop avoiding the big moments in her characters’ lives. She looked at me despicably and said, “That’s because you like action.” Guilty!

When I’m writing a novel, I tend to read more non-fiction, especially history and biography. Lately I’ve been reading sports biographies, The Last Hero about Henry Aaron and Satchel, about Satchel Paige. I’m not writing about baseball but these books are illuminating on the subject of the individual’s struggle.

And of course I’m always reading as an editor. I’m very lucky to have an inbox that receives new manuscripts from novelists like David Mitchell, Gary Shteyngart, Charles Bock, John Burnham Schwartz, and Stefan Merrill Block. I edit Billy Collins and sometimes he’ll email a new poem, which is like the shard of a star falling from the heavens and landing on my desk. The same is true for my nonfiction writers. I edit the presidential biographer Ronald C. White, Jr. Lately he’s been emailing chapters from his new biography of Ulysses Grant. Each of Ron’s chapters is an afternoon walk at the side of a great, great man.

Obligatory question: any advice you can give the young writers of today?

Read a lot and write a lot. And, write the book you’d want to read. Curtis Sittenfeld has said this same thing another way: be sincere.

Another obligatory question: favorite short story writers?

Chekhov and his heirs, Eudora Welty and Alice Munro. But I have to add that some of my favorite fictions are the long stories or short novels of Melville and Tolstoy. Billy Budd, Bartleby, Benito Cereno, Hadji Murad, The Death of Ivan Ilyich, Master and Man—these are some of the capstones of my reading life. I’ve read Hadji Murad more times than any other book. I teach it nearly every year.

Your first novel, The Danish Girl, is being adapted for film, but I recently read another one of your works is also being adapted. Have you been given certain creative consult to these projects? Or do you view the book-to-film adaptation similar to Cormac McCarthy, who simply doesn’t wish to blend the mediums?

Your first novel, The Danish Girl, is being adapted for film, but I recently read another one of your works is also being adapted. Have you been given certain creative consult to these projects? Or do you view the book-to-film adaptation similar to Cormac McCarthy, who simply doesn’t wish to blend the mediums?

I made one request to the producer of The 19th Wife: to keep the dog in the story. Last week I visited the set in Calgary. There’s no dog. McCarthy’s right: it’s another medium. Let them do what they will. Caleb Carr once told me not to bother trying to influence the adaptation because even if they give you a role, you have no role. But you know what I find astonishingly dull? Writers complaining about Hollywood. If you can’t stomach a bad experience with film, don’t sell the rights. If you do sell the rights, be grateful and get back to the keyboard. You don’t hear these writers complaining when they cash the check.

With The 19th Wife, you’re currently enjoying the best success of your literary career so far. What’s next?

A novel called The Record Book. It’s about family and sports as a means and metaphor for the American dream; and the underside of that noble belief.