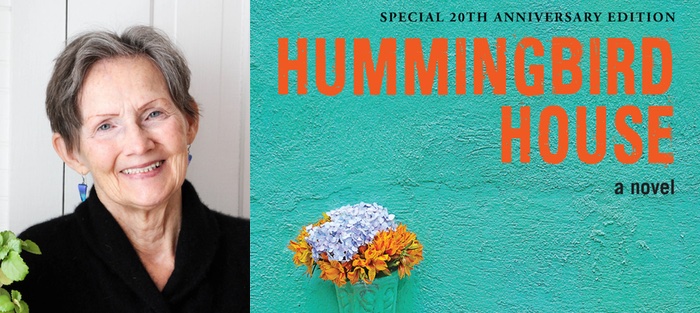

In her life and in her writing, Patricia Henley is an adventurer.

At 72, she is lithe and just starting to gray, an outdoorswoman, a hiker and backpacker, a onetime commune dweller, a world traveler (she’s just home from a genealogical trip to Poland, Germany, and the Czech Republic), a feminist, political activist, mother, grandmother, and animal lover. She has published two poetry chapbooks, two novels, four short story collections, a young adult mystery (a collaboration with Elizabeth Stuckey-French), a play, essays, and micro-memoirs.

Retired from a 27-year teaching post at Purdue, she now lives in Frostburg, Maryland, with her two dogs.

I first read Patricia’s work when I was in Wyoming for my wedding in 1990; my husband gave me his treasured copy of Friday Night at Silver Star (Graywolf, 1986)—elegant, vivid, earthy stories of aging hippies remaking their lives in a vast and arid landscape. I fell in love with the West and with Patricia’s writing.

Years later, when I began writing fiction, I wanted to learn Patricia’s magic. I called her. I couldn’t leave my job in Raleigh and move to West Lafayette, Indiana; would she consider taking me on as a long-distance apprentice? She was game. She mentored me through a first draft of my novel Byrd.

A few of the lessons she emblazoned on me: to be a good writer, be a good person. Pay attention. Learn people by listening to them. Learn a place by being there, absorbing it. Keep an open mind and an open heart. Take good notes. Make time for solitude. Cherish solitude.

Patricia is that rare creature: as good a person as she is a writer. She taught me what it means to be a literary citizen.

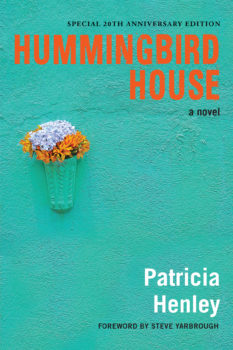

We corresponded in anticipation of the “rebirth”—her word—of her first novel. Hummingbird House (MacMurray & Beck, 1999) is the story of Kate Banner, a middle-aged American midwife working in Central America in the turbulent 1980s. A heartrending, beautifully crafted, timeless account of love, war, and doing the right thing against all odds, the novel was a finalist for the National Book Award and the New Yorker Fiction Prize. In November 2019, Haywire Books released a twentieth anniversary edition.

Interview:

Kim Church: How did the rebirth of Hummingbird House come about, and how are your hopes and expectations for the book different now than when it was first published? How are you different?

Patricia Henley: Jon Sealy, publisher at Haywire Books, was looking for a novel by a woman that would have the scope of Hummingbird House. I had been casting about for a publisher who wanted to bring it out again. It had been out of print for a decade or more. I said to Jon, “Why not Hummingbird House?” He liked the idea. We have a great working relationship and I’m thrilled with what he’s doing at Haywire. Bringing out books that matter in our “haywire” world.

Patricia Henley: Jon Sealy, publisher at Haywire Books, was looking for a novel by a woman that would have the scope of Hummingbird House. I had been casting about for a publisher who wanted to bring it out again. It had been out of print for a decade or more. I said to Jon, “Why not Hummingbird House?” He liked the idea. We have a great working relationship and I’m thrilled with what he’s doing at Haywire. Bringing out books that matter in our “haywire” world.

I don’t think I had many hopes and expectations in 1999. It was satisfying to have the book in print after having spent almost a decade researching and writing—with long breaks for other writing, teaching, and what we call real life. With this edition, I hope it might shed light on the plight of immigrants from Central America wanting to relocate in the USA. I doubt many people in our country have a visceral sense of what life is like in Central America.

How am I different? I was younger then, and passionate about my subject matter. Nothing could dissuade me. I took some risks. I was sometimes nervous, but I also knew I was privileged and could get away with certain things in Guatemala. Or, I hoped I could. So many writers, artists, bookstore owners, social workers, lawyers, anthropologists, and activists were killed during the violence there during the civil war. I didn’t want to be one of them. I’m different now in this way: I’m not inclined to go to dangerous places. What protected me then—being a citizen of the USA—would not protect me now. I am in awe of the men and women who go to do good work in dangerous places.

In her review of the book for Hungry Mind Review, Donna Seaman wrote: “Henley renders her heroine’s thoughts with the sort of nurturing attentiveness one hopes for in a physician: she is specific and calm without being clinical or distant.” That calm specificity draws us in and creates absolute trust, so that we are accepting when you do the unthinkable and end the novel with an imperative. Two imperatives! What a bold and brilliant stroke, that ending, and how perfect. I know of no one else who could have written it or would have dared to try. When in the process of the book did it come to you? Did it come whole or did you labor over it?

Hmm. I wrote the ending when I was about three-fourths of the way through the manuscript. I wrote it so that I could work toward it. I had to discover that romance was not going to be Kate’s consolation or the reader’s consolation. The ending came to me whole, in a way, as if I were channeling it. Many times while writing this book I felt as if I were merely a conduit for something that needed to make its way in the world.

For all the dark politics at play in the novel—notably, US involvement in covert wars in Central America—and for all the fatigue and heartbreak your protagonist suffers, there is a sort of beleaguered optimism undergirding the story, a faith that good people will continue to do good no matter what. Is that still your hope, even in the current political climate?

In spite of everything, I hold out hope. I have enormous hope in young people. The ones I know are so savvy, so tolerant of differences, so loving, so creative. And after we went through the big shift, from Obama to the present administration, it felt like people with good ideas and good intentions really galvanized. We have fight in us.

Yes we do.

Mary Chapin Carpenter sings, “We are the places that we’ve been.” Your work, wherever it’s set, is always solidly grounded in place. Could you have written Hummingbird House without going to Central America? To what extent did the story arise from the place?

I advise against setting a novel in a place you haven’t visited. And why would you? When, if you go, so many aspects of the novel will be present and make the writing easier. I first traveled to Guatemala in 1989. A British doctor handed me the idea for the novel with a story about an American priest who had died during the violence. If I hadn’t gone, if I hadn’t been standing on that street corner, talking to that doctor, in Antigua, during the summer of 1989, I wouldn’t have written this book.

You’ve written in almost every form—poetry, short story, novel, essay, memoir, play. Do you always let your material dictate form, or are you influenced by personal circumstances—like what kind of time commitment you can afford, and what you’re willing to sacrifice?

That’s a very good question. Right now, I’d like to start a new novel, but a construction crew is due to arrive to start building a new bathroom on my first floor. I can’t go out of the house to write because I have to manage the dogs during the construction. So I am working on more micro-memoirs. Sometimes material dictates form. When I researched the lives of prostituted women in Baltimore, I walked away feeling I couldn’t devote myself to that place and subculture enough to write a novel about it. The idea wore me out. A few years later, I came across my notes and realized that their voices alone gave me the material for a play. So I wrote “If I Hold My Tongue.”

You’ve worked with a big New York publisher, but more than many writers of your stature, you’ve been open to small presses and new technologies. You once described yourself as a “small press writer.” What does that mean? Where have you felt most at home?

Like most writers I have my publishing war stories. I’ve been lucky, too, of course. I think of myself as a small press writer, for the most part, because, although my books have received satisfying attention and have been, mostly, critically acclaimed, I’ve never had a breakout book. I have never sold huge numbers of copies. So big houses are just not that interested, once it becomes apparent to them that your work is not going to make a lot of money. That may be simplifying it, but that’s my initial response to your question. It’s like a mirror. They see you that way and you begin to see yourself that way. Small presses are the valiant foot soldiers in the literary world. Have you ever been to the book fair at AWP? What an amazing field of design, color, good work, surprises.

The AWP book fair is heaven.

Speaking of valiant foot soldiers: Haywire Books is a new independent press dedicated to “making sense of a chaotic world.” Your work confronts chaos that is almost impossible to make sense of—in Hummingbird House, women and children in wartime. Do you write with a mission? Or is it more a matter of writing from your own moral, political, social, and literary sensibilities with no conscious agenda?

With Hummingbird House my conscious agenda was to explore the lives of women and children in the civil war in Guatemala, a war that the USA had a hand in. I didn’t know what I’d find. I went where I was led.

You’ve produced an impressive body of published work; you’ve also squirreled away a few manuscripts. I’m a firm believer that nothing is wasted, everything can be scavenged. What will happen to the manuscripts in your desk drawers?

They may be burned! Along with a stash of love letters. I wouldn’t want my unpublished work to be published. There’s a reason why I abandoned it. But I’m still writing, so I hope to make use of some that material.

Before you retired from Purdue you began a new memoir to look, you said, at certain questions—what retirement would mean, whether you should move (you did), whether you wanted romance in your life again. What answers have you come up with?

I still enjoy teaching. I teach workshops, and I work with individual writers who want a coach and editor. But I love not being attached to an institution, with its attendant meetings and turf struggles. And I read what I want, with no concern about teaching what I’m reading. I like the freedom of getting up every day and letting writing be front and center in my life. I don’t have romance in my life. I’m not ruling it out. But I love living alone without the static of another person’s needs and wants. My new work is about this very thing. I’m working on a manuscript of micro-memoirs about embracing crone life.

You’ve spoken of your writing practice—early mornings with strong coffee and a notebook—in the way others might describe a spiritual practice. Has your practice been consistent over your career?

I met a Buddhist monk in San Miguel de Allende about fifteen years ago. I had been fretting that I couldn’t seem to establish a regular meditation practice, due to wanting that early morning time for writing. The monk told me to lay down that thought, that fretting. He assured me that my writing was my practice. My practice has been fairly consistent over a lifetime, from my early twenties, so for around fifty years. When I say that, I think, So why haven’t you produced more? But it all takes time, as you know.

How has the business of writing impacted you? What has made you happy? What will you never do again? What do you want to do that you haven’t done yet?

About the business of writing: I find it pesky. Like a fly that’s always buzzing around. I don’t want to be bothered with it, but when something good happens—I earn some money or I receive a magazine in the mail containing a piece by me—I’m glad to have taken the time to submit, to reach out. I suppose it has impacted me by keeping me down financially. Wouldn’t everyone like to earn more money? A New York editor once asked me, “When are you going to quit teaching?” And I thought, but did not say, “So who will pay my mortgage if I quit? Or put food on my table?” Money from publishing is not predictable for most writers.

But please don’t take those thoughts as sour grapes. I realize every day how lucky I have been. Some of my books are still in print. I have a stable life. I have my health and I am able to write every day.

What would I never do again? I probably would not co-write a book. Elizabeth Stuckey-French and I had such a good time writing that YA book, but it went into a black hole. I wonder if readers do not really want to read a co-written book. I think readers want to feel that one beloved writer is whispering the story right into their ears.

What would I like to do that I haven’t done yet? I’d like to publish a book of these micro-memoirs. The manuscript is called You Could Live Here. Meaning, in a world of your own making. I was inspired by Abby Thomas’s Safekeeping and Beth Ann Fennelly’s Heating and Cooling. Whenever I read from these micro-memoirs to an audience of mostly women, they respond so happily, noisily, as if what I am saying echoes their experiences in mid-life to late-life. I want to get this book out there, so that women will sense solidarity with other single women. There is still some vestigial pity for single women, left over, I suppose, from a time when getting married represented the pinnacle of womanhood. Now it doesn’t. And single women are loving their lives with a joy that the pitiers cannot possibly imagine.

I’m not single but I’m one of those happy, noisy women. I love the micro-memoirs you’ve published so far and can’t wait to read the collection.