When I was a child, I did not dream of becoming a writer. I was practical. l wanted to be Mrs. Bates, who with her husband ran the neighborhood store, a sturdy brick building on Cotton Grove Road. While her husband pumped gas, Mrs. Bates ran the cash register and scooped ice cream and sold penny candy. She was old and round and saggy and wore housedresses and she knew everybody and I loved her.

Okay, I didn’t want to be her exactly. I couldn’t imagine myself old or round or saggy. I just wanted a store. I wanted to be the center of a community. And sell candy.

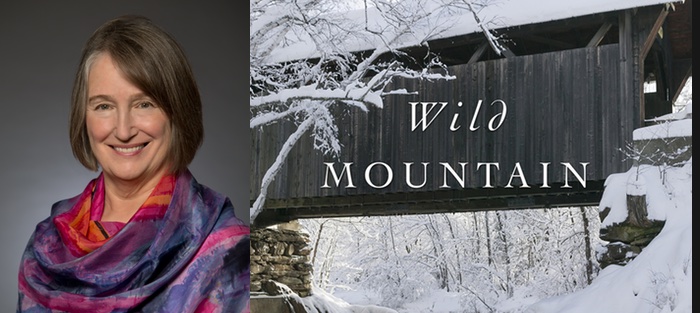

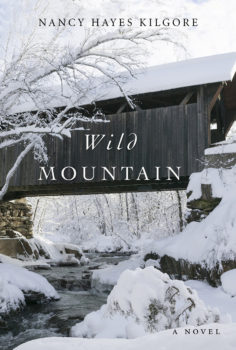

What a delight, then, to meet in fiction the person I had always wanted to become: Mona Duval, a central character in Nancy Kilgore’s new novel, Wild Mountain (Green Writers Press). Mona (who is not old or round or saggy) runs the general store in her small Vermont community. She is devoted to the place—its history, its natural beauty, its people. She and the store and the 200-year-old covered bridge beside it are the literal center of Wild Mountain. When an ice storm collapses the bridge, Mona is devastated. She and part-time Vermonter Frank McFarland organize an effort to restore it, but meet with surprisingly emotional resistance. Tensions over the bridge betray a deeper political schism over a same-sex marriage bill.

Meanwhile, Mona is facing her own crisis: her dangerous ex-husband is back in town. As she works to bring together opposing factions in Wild Mountain, she makes her way toward her own center.

I felt at home in the world of this novel. I looked forward to spending time with the characters and was sorry to leave them when the book ended.

I had the same reaction to Nancy when we met several years ago at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. Like Mona, she is earthy and wise and genuine, with a deep, quiet strength—all of which comes across in her writing. She and I share a love of rural landscapes; we’re both married to painters; we both work in helping professions outside academia; and, as I learned in this interview, we’re both fans of George Eliot. No surprise—Wild Mountain is in many ways reminiscent of Eliot’s Middlemarch: the story of a small community on the brink of social and political change (in Middlemarch, the first Reform Bill is pending in England; in Wild Mountain, it’s the Freedom to Marry bill). Both novels teem with vibrant, memorable characters. Both move right along—as the narrator of Middlemarch tells us, she doesn’t have time to linger and chat; there’s a lot happening, and she has “much to do in unravelling certain human lots, and seeing how they were woven and interwoven.”

I’m grateful to Nancy for pausing to chat with me about Wild Mountain.

Interview:

Kim Church: If I had to describe Wild Mountain in a few words, I would call it a love story about a place, a valentine to Vermont. Even the characters, diverse and complex as they are, seem, as an ensemble, emblematic of Vermont—farmers, aging hippies and back-to-the-landers, roughnecks, adventurers, freethinkers. Tell me about the genesis of the book. Did it begin with a place, a character, or something else?

Nancy Kilgore: After writing my first novel from the perspectives of two women, I wanted to challenge myself to write from a man’s point of view. I had an old friend a bit like Frank—intellectual, charming, a wanderer. And I knew of a Vermont bridge that had collapsed. My idea was to pair the male character with a grounded native Vermont woman in an ice storm that collapses a bridge.

Wild Mountain started as a short story, and was published as such in a literary magazine. But then, as tends to happen, I began to see more characters and a larger situation, and the story became a novel.

A lot of the tension in the novel arises from political controversy. There are two issues brewing in Wild Mountain: plans for reconstruction of the old covered bridge, and a same-sex marriage bill—disparate issues that become closely interwoven. What gave you the idea to braid the two controversies?

A lot of the tension in the novel arises from political controversy. There are two issues brewing in Wild Mountain: plans for reconstruction of the old covered bridge, and a same-sex marriage bill—disparate issues that become closely interwoven. What gave you the idea to braid the two controversies?

They seemed to evolve together naturally. A lot of financially struggling folks in Vermont cringe at paying more taxes, and to them, restoring historic landmarks may seem an unnecessary expense. Back in the ’00s, some of the same conservatives also opposed same-sex marriage.

Anne Lamott has said that every writer must have a moral position. Do you agree? What does that mean to you?

I’m not sure what she means. Someone said that for a novel to be satisfying, the writer needs to have compassion for all the characters—in that sense to play God. I agree with that. In the end, even the bad guys need to be seen with some sympathy. Maybe that’s a moral position.

Yes—even a spiritual one. To believe in and find the spark of divinity in every character.

Unless you’re writing a murder mystery, I suppose.

One of my favorite things about reading and writing fiction is getting to know characters through their work. I love the choice you made for Mona: she runs the general store. She “likes being at the center of the community, the still point in the storm”—a description that’s true on many levels. Your first novel, Sea Level, also features a character who’s a central figure in her community—a minister, like you.

Having a point-of-view character whose work places her in the heart of a community is a great way to immerse the reader in that community. Did you consciously choose this perspective for Wild Mountain, or is it one that comes to you naturally?

I don’t think I’d thought of it in that way, but that’s true. I think in most novels, the central character becomes the hub of action, but some stories are more what I call introverted. I think my writing tends to be extroverted. I want to include a whole world—the community, the environment, the political and historical context. As I worked on both novels, these elements grew up around the central characters.

There’s a lot happening in this book, both in the community and in the private lives of the characters. There are also what I think of as resting moments—when the action pauses and the characters settle into the present. Many of these moments take place in nature, which you describe with exquisite reverence. Many take place in Mona’s store.

Soft sunlight floated into the room on streams of dust motes.

Charlie walked away to find his Hormel chili and Miller Lite.

Sierra and Grace were standing at the counter, which was piled with two large bags of barbecue Doritos, one of them open, a six-pack of Mountain Dew, three pints of Ben & Jerry’s chocolate chip cookie dough ice cream, a bag of gummy bear candy, and a box of Tampax.

Mona banged two copies of The New York Times on the counter and shuffled a basket of moose candies from side to side. Each maple sugar moose, wrapped in cellophane, was big as a child’s fist, and they made a crackling sound as she handled them.

I think the real magic in this book is how, like Mona, you’re able again and again to bring us so effortlessly to center, to a still, ordinary, present moment. Is this a natural rhythm for you, or is it something you work at?

Kim, I love the way you describe the resting moments and coming into the present. I do like to visualize a scene and describe the sensory surroundings, and that does bring the reader into the present. It’s something I learned as a writing student at the Radcliffe Writing Seminars (my teacher was a mentee of Wallace Stegner, one of my heroes). I also have a meditation practice and have studied and used meditation as part of my therapy practice. That’s all about coming into the present moment, so maybe it’s related.

The town of Wild Mountain is at odds over the Freedom to Marry law. Percolating under that conflict are larger questions of freedom. These characters, while products of their place and history and faith and heredity, are learning that they can still choose their lives—whom to love, what to hold sacred, what to protect, what to sacrifice. Did you set out to explore the theme of freedom, or did it emerge as you wrote?

Again, your reading makes me ponder. I hadn’t thought of freedom as a theme, except for the freedom to marry issue. But I like that perception. And it did emerge: Mona learning to be free from her fears and preconceptions about men, Frank from his need to keep running, and a community learning to be free from the fears that divide it.

What do you read when you’re working on a novel? Whose writing influenced this book?—if that question applies.

Nancy Kilgore (Photo by Kathy Tarantola

I’m always reading novels. I read mysteries as well as literary novels, and everything I read, good, bad, or indifferent, seems to teach me something about writing that I can incorporate into my thinking and my practice—what to do and not do. I love Wallace Stegner, especially his last two books, and among contemporary writers, Tana French—her first two novels—and Jojo Moyes. Books I read over and over are Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse and Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It. In high school I was weaned on George Eliot, Thomas Hardy, and Tolstoy. I think Eliot engrained in me the idea that a “real novel” includes a whole community.

This is your second novel. Did the experience of your first novel help or hinder you in any way? What advice would you give other writers working on second books?

Oh, you’d think it would be so much easier the second time. And in some ways it was. I’d written a novel before, so I knew it was possible, at least. But still, it’s a slow process for me, getting through the fears and doubts and then coming back to writing, then being stymied by thoughts like I can’t do this or this is not earning money. But then I remember that I love this process of creation, and whatever comes out the first time, I can always revise. I get immersed in the place and time and the characters’ lives. My advice is nothing original: just keep writing.