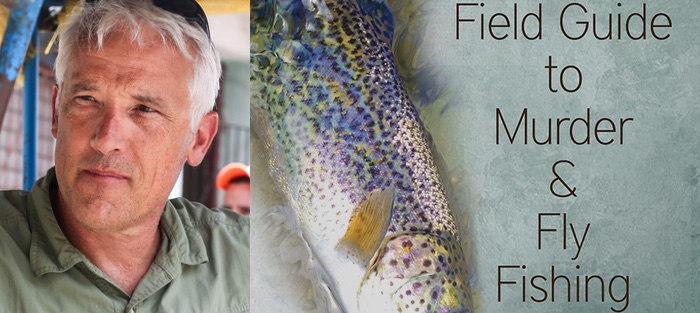

Upon reading Tim Weed’s gripping account of a backcountry ski trip (“Mice in the Land of Gog”) I enrolled in his class at Grub Street, expecting (and finding) a kindred spirit. Tim’s love and eye for the outdoors are matched only by his love for writing. Both have been enriched as a guide for National Geographic Expeditions in places such as Cuba, Spain, and the far reaches of South America. His lifetime of adventure is on display in compelling and immersive fictional backdrops that explore the desires and messes we repeatedly lurch into as human creatures—but often don’t want to admit to.

In addition to Grub Street, Tim teaches in the MFA Creative & Professional Writing program at Western Connecticut State University. He is the winner of a Writer’s Digest Popular Fiction Award and a Solas Best Travel Writing Award. His short fiction and essays have appeared or are forthcoming in Colorado Review, Gulf Coast, Talking Points Memo, The Millions, The Rumpus, Writer’s Chronicle, and Backcountry, to name just a few. Tim’s first novel, Will Poole’s Island (Namelos, 2014), was named one of the Best Books of the Year by the Bank Street College of Education.

In his classes, Tim sometimes likens good fiction to a bag of potato chips: impossible to stop after just one bite. His short story collection A Field Guide to Murder and Fly Fishing (Green Writers Press, 2017) rises to that high standard; I found myself consuming its thirteen tightly wound tales with addictive delight. The diverse settings would be enough to keep one reaching into the proverbial bag: Colorado, Spain, Rome, the Andes, the Alps, the Venezuelan rain forest and Tim’s native New England, including Nantucket. The character milieus are at least as varied, realistic and colorful.

I had the pleasure of interviewing Tim about this unique and enchanting collection.

Interview:

Art Hutchinson: Lurking beneath many of these stories seems to be an undercurrent of conscience, of a character testing the boundaries of a moral framework or code that is never made explicit. Can you talk about where that comes from? What kind of intentionality do you have in getting your readers to think about that kind of conflict?

Tim Weed: That’s an intriguing line of questioning, and the truth is that I’m not really sure. It may be that the code is never made explicit because the stories themselves were my subconscious way of searching for the true nature of that code: plumbing its shape, its content, its limits. It hasn’t really been my intention as a fiction writer, though, to get my readers to think in any particular way. I guess I view my role more as one of placing my characters at a specific point of instability—emotionally, psychologically, and/or in relation to the actual physical landscape—and then letting things play out to some kind of inflection point leading to a new equilibrium. To put it another way, what I’ve hoped to do is to tell an entertaining story that carries a certain ballast of unarticulated meaning. Does that make sense?

You do a great job enticing your readers to empathize deeply with your characters’ subjective, situational moral rationalizations (e.g., not giving too much away: even for murder!) Yet as a collection, I couldn’t help noticing a veritable table-run on the Ten Commandments. You empanel us on a virtual grand jury to consider if the character should be set free because objective morality might not exist. What would a Dorothy Sayers review of a Tim Weed story look like?

Let’s hope she would approve! We’ll never know, so the best I can do is quote Chekhov: “Let the jury judge them; it’s my job simply to show what sort of people they are.”

Most of these stories seem to invite the reader to explore the boundaries of conscious experience, whether that be the thrill of extreme sports (fishing, skiing, cliff-diving, etc.), the supernatural (ghosts, evil omens, etc.) or mind-altering drugs. What fascinates you most about those boundaries? Are they all the same? What connections would you hope for your readers to make?

Most of these stories seem to invite the reader to explore the boundaries of conscious experience, whether that be the thrill of extreme sports (fishing, skiing, cliff-diving, etc.), the supernatural (ghosts, evil omens, etc.) or mind-altering drugs. What fascinates you most about those boundaries? Are they all the same? What connections would you hope for your readers to make?

It was once pointed out to me by the great Robert Stone that there are two stories we all carry with us, the exterior story and the interior story, and that where these two stories meet is viable ground for literature. The inner landscape is something fiction can do far better than any other narrative art, and this is intrinsically mesmerizing to us as readers— because it’s the closest approximation we have to actually living the experience of another human being.

To me, the vicarious power of fiction is the reason that is will never be completely supplanted as an artistic medium by moving pictures, even with all the excellent television dramas we’re seeing these days. The nexus between outer and inner experience is something that I’ve set out to explore in my fiction, and I enjoy the artistic freedom that nexus offers to a writer. Because fiction unfolds as refracted through a point-of-view character’s mind, it’s an art form that can easily push the limits of objective reality. The fiction writer is free, in other words, to play around with perception in interesting ways, including occurrences that one might consider visionary or hallucinatory. I suppose this is why I’ve been drawn to settings and experiences that might be considered out of the ordinary.

I understand you’re fluent in Spanish. Several of your stories are set in Spanish-speaking countries (Venezuela, Spain, Cuba, and an unnamed country in the Andes). I just took my first trip to South America last year (Colombia). What do English-speaking readers understand least about Spanish-speaking cultures? What can you do in those settings in a story that you can’t do elsewhere?

In the course of my “other” academic and professional career—international educational travel—I’ve spent several cumulative years immersed in foreign cultures, including periods in Spain, Mexico, Ecuador, Venezuela, Argentina, Peru, and Cuba. I was a Spanish major in college, and when I first went abroad to study I discovered one of the great benefits of spending an extended time immersed in a different culture and language: it results in the creation of a new, alternative center—intellectual and emotional—from which to perceive one’s surroundings. It’s not just a question of an enlarged perspective. In a very real sense it’s a redoubling of perspective, because adapting to life in a different culture and language requires the construction of a brand new mindset from which to perceive the world; in effect it requires you to become, at least temporarily, a completely new person. For me, there are key similarities between this forced redoubling of perspective and the capacity to inhabit alternative worlds that is part and parcel of fiction. The muscle groups aren’t exactly the same, but they’re related.

Having said that, in most of my fiction I haven’t felt comfortable writing wholly from the perspective of a person outside my own culture. For the most part, in stories with international settings, my point of view characters are native English-speakers experiencing different cultures. As a writer and as a reader I gravitate to narratives that take characters to new and unfamiliar places. Such narratives force characters to actively notice the world, which is something I find both intrinsically alluring and pragmatically useful in triggering a reader’s immersion in the story.

Thinking about your last two responses together, and the collection as a whole, you seem to be suggesting that immersion in other cultures and languages can challenge our assumptions about reality almost as much as meeting a ghost or dropping acid. Is that what you’re getting at? What are the distinctions, if any?

I think that’s a perceptive comparison. Challenging or pushing our perceptions of reality is another fiction’s comparative advantages—something it can do better than other art forms—and, as we’ve already mentioned, alternative or exotic versions of reality are a catalyst for immersive fiction. In this sense drug trips, supernatural encounters, and experiences in settings and cultures that are markedly different from those we’re used to all fall into the same category: experiences that take us out of the quotidian, forcing us to actively notice our surroundings as filtered through a highly particularized interiority.

You’ve spent a lot of time in Cuba and are currently working on a novel set there. Your story “The Money Pill” is set there also. How did you come up with the idea for that? How are the dynamics you describe changing with the opening up of Cuba? What elements are least likely to change? How would you compare your fictional Cuban world to the one Hemingway wrote about?

I’ve been fascinated by Cuba ever since I first went there in 1999 to scout a new student travel program. There’s a magnetism about the country that’s impossible to express: a complexity, a cultural depth, combined with an extreme lack of transparency that I find endlessly interesting. “The Money Pill” grew out of some experiences I had in eastern Cuba during the early 2000s. As is the case with many short stories, I suspect, this one grew out of a sense of paths not taken, of experiential opportunities that seemed to point in interesting directions if one were to follow up on them. In reality, one didn’t follow up. In fiction, one did.

I’ve been fascinated by Cuba ever since I first went there in 1999 to scout a new student travel program. There’s a magnetism about the country that’s impossible to express: a complexity, a cultural depth, combined with an extreme lack of transparency that I find endlessly interesting. “The Money Pill” grew out of some experiences I had in eastern Cuba during the early 2000s. As is the case with many short stories, I suspect, this one grew out of a sense of paths not taken, of experiential opportunities that seemed to point in interesting directions if one were to follow up on them. In reality, one didn’t follow up. In fiction, one did.

Writing “The Money Pill” led me to an understanding of an important issue of power dynamics that must be faced in one way or another, not only in Cuba, but anywhere you have people traveling from a rich country to a poorer one. So it was well worth exploring I think, though of all my protagonists that one is probably the toughest to like. But because it was fiction, it allowed me to go places I wouldn’t have gone otherwise, and in in the process of exploring these untaken paths, to come away with a new and deeper understanding of reality. It occurs to me that this may be relevant to your first question about the nature of the underlying moral code.

Yes. That story suggested to me something tenacious and universal in the human person that wealth or culture or secrecy can never quite obscure. The characters seemed worlds apart and yet surprisingly similar in some ways. I’m still interested in Hemingway though. Is the Cuba he wrote about still discernible?

Very much so. Which is one of the reasons it remains such an interesting place to go. To paraphrase Faulkner, the past isn’t even past in Cuba. It’s like nowhere else, with all the layers of the country’s fascinating history right there in front of you, ready at hand to see and smell and touch. Hemingway’s principal residence was Havana for nearly thirty years, fully half his crowded life. It’s impossible not to perceive him there. His troubled ghost still wanders the streets of Habana Vieja. His essence floats on the breezes that wash his hilltop estate at the Finca Vigía.

“Diamondback Mountain” is the one story in the collection that’s set in a timeframe (1930s) that you could not have experienced yourself. What led you to choose that setting? How did you go about framing it? What was hardest about capturing its essence?

“The past is a foreign country,” as the famous line goes. I’ve found it to be true, and in this sense historical fiction is a good fit for my interests as a writer. Historical fiction requires the creation of an alternative world. A major part of building a fictional world involves descriptive writing, or “noticing,” which is a key trigger for the kind of immersion that I’m drawn to in fiction. “Diamondback Mountain” is unique in the collection in that it represents a fragment—the boiled-down essence, really—of a failed novel project. So I actually spent several years immersed in research, both archival and experiential, into the American ski culture of the late 1930s. I was immensely drawn to the setting of “Diamondback Mountain.” It still holds a deep emotional magnetism for me.

The research I did for that failed novel included a cover-to-cover read of every issue of Appalachia—the Appalachian Mountain Club’s beautifully written and illustrated magazine about mountain adventure and exploration—published between 1928 and 1942. Those issues hold a place of honor on the bookshelf in my writing studio; they are among my most prized literary possessions. When I put this type of primary source together with the aura of certain family legends—and with my own firsthand experience in the Rocky Mountain backcountry—I became versed enough in the setting that I felt comfortable writing “Diamondback Mountain,” though the events it describes take place half a lifetime before I was born.

So, I’m still curious. For the “failed” novel, how did you latch onto that setting? I know you’re a big skier and outdoorsman, but why 1930s Italy? Should we infer a nod in Hemingway’s direction here too or would that be going too far?

Not Hemingway so much as the world he belonged to. A lost world that was also the world of the youth of my grandparents, two of whom I knew well and for whose early lives I harbored a certain amount of fascination. The late John Fowles used to talk about the psychological concept of the “domaine perdu,” which is an inchoate longing to return to a lost world of sensory completeness that drives us as writers to try to create the kind of vivid, concentrated descriptive prose that will bring this lost world back to life. It’s a fascinating argument really, which I’ve written about elsewhere. I see it as pertaining more to novels than to short stories, so it makes sense that of all the stories in the collection this one would be the most imbued with it.

Of course, Hemingway was all about the domaine perdu. There’s this quote of his that I love:

“All good books are alike in that they are truer than if they had really happened and after you are finished reading one you will feel that all that happened to you and afterwards it belongs to you; the good and the bad, the ecstasy, the remorse and sorrow, the people and the places and how the weather was.”

I consider this a rigorous and highly admirable ambition for what fiction can and should do.