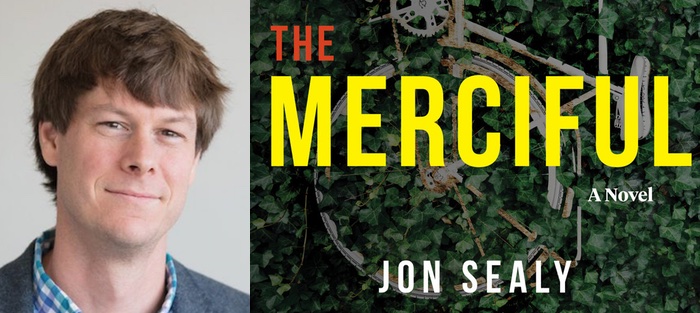

Everyone in the small, picturesque town of Overlook, South Carolina, has an opinion about the death of nineteen-year-old college student Samantha James. After all, although the facts seem straightforward— Samantha was on her bicycle, pedaling along a dark, but familiar, country road to meet her boyfriend, when she was hit by a car driven by Daniel Hayward—there are a slew of questions about what she was doing out so late. Hayward, too, is the subject of debate, and people disagree about whether he should be charged with vehicular homicide or murder.

Still, there’s one thing the townspeople agree on: after plowing into Samantha, Hayward called neither police nor medics and she was left on the side of the road to die alone.

It’s a sad, if common, tale of a life cut short by the seemingly cavalier arrogance of a man who is assumed to have acted irresponsibly.

Not surprisingly, many of Overlook’s people are outraged, furious that Hayward left the scene of the crime. Worse, many are skeptical of his account, refusing to believe that he thought he hit a deer, saw nothing when he got out of his car to investigate, and then drove home. Many wonder if Hayward was drunk, speeding, or otherwise compromised.

It’s a tense set-up, and in The Merciful (Haywire Books), Jon Sealy explores the incident from multiple perspectives—zeroing in on Samantha’s parents and sister, the prosecuting and defense attorneys, Daniel’s wife, and his college-era best friend, among them. The result is a thought-provoking and unsettling interrogation of what we think we know.

Interview:

Eleanor J. Bader: In September, the Attorney General of South Dakota, Jason Ravnsborg, was involved in a traffic incident in which a man was killed. He told police that he thought he’d hit a deer. The account seemed to come straight out of The Merciful. Have you followed the story?

Jon Sealy: Before I started working on this novel in 2015, I didn’t realize how many accidents like this there actually are. I live in Richmond, Virginia, and several years ago there was a tragic accident that made the front page of the newspaper. It was a similar kind of deal in which it took a few days for the man who hit a bicyclist to come forward. When he did, he said he thought he’d hit a deer.

I did a little research into South Carolina law since that is where The Merciful is set, and several cases popped up in which this was the defense. The South Carolina low-country gets country dark and there are deer all over the place. I assume it’s the same in South Dakota but it’s still eerie when things in real life imitate art!

Many early reviewers of The Merciful call the book a morality play. Was this your aim?

Many early reviewers of The Merciful call the book a morality play. Was this your aim?

I don’t know if I had an aim, exactly, but I was thinking about Kierkegaarde’s contention that “subjectivity is truth.” We are all in our subjective experience and there are always multiple realities happening at the same time. I used to work as a newspaper reporter, so I’m interested in how some stories bubble up and others don’t.

The Richmond bicyclist case I mentioned a few minutes ago got front-page press coverage for days. Meanwhile, a second hit-and-run, in which a man was killed after coming out of a bar, got just one column. Why does one death become big news and another doesn’t? As I dug in, I realized that news shapes the narrative but there is a lot of complexity to what we’re hearing and seeing and what we’re not hearing and seeing.

Daniel reportedly once told Jay, his college best friend, that “sometimes you have to shatter your life.” He said this when he was in his early twenties and he certainly does this in the novel, with the accident precipitating a series of negative events including the break-up of his marriage.

Yes. It’s braggadocio when he says it as a young man, but he couldn’t have anticipated what it might look like in middle age.

Daniel’s wife, Francine, calls Jay when Daniel is charged and asks for his help. While Jay goes back and forth about what to do, he ultimately does nothing. At the same time, the novel is narrated by Jay and the story is told from his perspective. Nonetheless, he didn’t call, write, or visit Daniel. I found this disappointing and it made me dislike him.

I wrote multiple versions of Jay and there were some versions in which he went to Overlook to see Daniel, but ultimately, not going felt truer to life. Jay had not seen Daniel for more than a decade and they were no longer close.

You remember how Thoreau goes to jail for not paying the poll tax? Most of us—Jay included—would grumble and then pay the tax. Jay takes the easier road of writing the story rather than getting involved.

In the end, though, I wanted to explore more than friendship. One of the undercurrents throughout the book addresses a fundamental question about what it means to be human. To my mind, consciousness is the ability to use memory to create a narrative. The story you read in The Merciful is filtered through Jay’s brain. He is bringing his subjective experience to bear on the facts, so it gives you a window into the process of framing a story.

Francine, Jay’s wife, abruptly leaves her husband as soon as the story hits the news. This seems pretty cold. It also works to make Jay more sympathetic.

Francine probably already had one foot out the door and the accident was the impetus, the permission, she needed to do what she wanted to do. Daniel is not the greatest dude. He also had one foot out the door, and the pressures of a trial on their marriage would be enormous. This is a commit-or-not moment.

There’s also a thread in which people blame Samantha, as if she is at fault for the accident because she was out on her bike late at night. I found this realistic but aggravating.

I was trying to write the idea that there are many interpretations of what’s going on. I certainly don’t want Samantha to be seen as at fault, but she was riding on a dark road at night, which isn’t the safest thing. I say this as someone who used to be an avid bike rider and who likes the idea of sharing the road. But it’s a risk to ride the road at night, particularly now that so many drivers are distracted by cell phones.

I see this book as a counternarrative, demonstrating that there can be several compelling realities that are in competition with one another among people who are close to the culprit and people who are close to the victim. Both see the same thing from different angles.

Jay’s lawyer, Henry Somerville, is a “good old boy” who has plied the legal trade for decades. But unbeknownst to him, a stranger shot a video of him playing with his dog. The video made it seem as though he was abusing his pet. It went viral and #DogJustice began to trend. It’s pretty absurd.

Viral public shaming has been going on for a while. Jon Ronson’s So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed is a great nonfiction book about it. He tells the story of Justine Sacco, a public relations professional who put a sketchy joke on Twitter and then boarded an eleven-hour flight to South Africa. It turned into a hashtag and ruined her life: #hasjustinelandedyet.

Henry was just playing with his dog when this false narrative about animal abuse went viral. Here is Henry, a man who is self-entitled, being brought to public justice for something he is innocent of. I liked the irony of that. Henry is sometimes a real jerk, but he is getting hammered for the wrong thing. The viral video shows one frame but there is a lot beyond the frame.

I wanted to juxtapose this incident with Henry’s defense of his brother Phil, who was arrested after a hit-and-run accident that left a man dead. Phil was able to pay off the victim’s wife off in exchange for her silence. I wrote these scenes to think about the ways social media can both democratize public justice or create a false narrative.

Let’s switch gears. The Merciful is being published by Haywire Books, a company you founded. Can you talk about what motivated you to start your own publishing company?

My first novel, The Whiskey Baron, came out from Hub City Press in Spartanburg, South Carolina. For the longest time, they only published one first novel a year, so for my second book, The Edge of America, I was out of a publisher. I worked with several agents, but they were unable to sell the novel. I kept hearing, “This is really good, but we don’t have a slot for you.” The slots always seemed to go to debut novelists or well-established writers, whereas I was in the mid-list.

Many of my writer friends were hearing the same thing and were also casting about unsuccessfully trying to find a publisher. I saw this as a gap in the market, so I said, “I’ll start a press and see what happens.”

I’d originally planned to do two books a year, but the pandemic has killed in-person books tours, which were central to my business plan. Last summer, I published Heather Bell Adam’s The Good Luck Stone, which has “book club” written all over it. It’s selling okay for a small press book that was put out in the middle of a pandemic.

There are two major pressures today, and they boil down to too many writers and not enough readers. People have these addictive entertainment machines in their pockets, which have taken a bite out of book readership. I don’t see that changing.

Do you see yourself fitting into the genre of Southern fiction?

I actually don’t think that Southern writing exists anymore, but it’s the tradition I come out of. In the early 2000s, I went to a reading by Ron Rash, author of One Foot in Eden, and George Singleton, author of The Half-Mammal of Dixie. These were break-out books for them.

They did an event in a book shop in Clemson, South Carolina. Until that moment, most of the writers I’d read were either dead or from someplace else. Here were these two guys making art from the South Carolina back-country. They knocked my head off, but I think they were the last of the genre.

The world has changed. I’m an elder millennial who grew up watching MTV. Younger folks grew up with cell phones and the internet which plugged them into the world beyond place, beyond region, into a digital universe. I think that’s killed the idea of Southern literature. People are not connected to place in the way they used to be.

What do you see as the consequences of this?

Much of what now passes as Southern literature leans into stereotypes of Southern life. This is particularly noticeable in Appalachian writing where you have these crime novels about meth dealers and hardscrabble junkies in mountain hollers. It’s sort of like a Pottery Barn version of the South, where people are buying reclaimed barn wood to hang on their walls. There’s some element of the real-world South in it, but the story of the South has become a commodity in many ways, even as the region itself has come to resemble the rest of America.