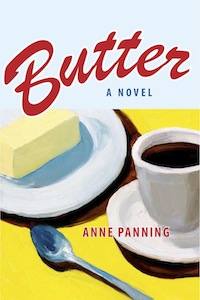

In Butter, her first novel, Anne Panning tells the coming of age story of Iris, an adopted eleven-year-old growing up in the 1970s in the small, fictional Minnesotan town of Wishbone. The innocent world around Iris begins unraveling just as she begins to navigate her role in it. Butter blends essential tension, observation, mystery, and setting into a delicious story befitting its title.

In Butter, her first novel, Anne Panning tells the coming of age story of Iris, an adopted eleven-year-old growing up in the 1970s in the small, fictional Minnesotan town of Wishbone. The innocent world around Iris begins unraveling just as she begins to navigate her role in it. Butter blends essential tension, observation, mystery, and setting into a delicious story befitting its title.

Panning’s short story collection Super America won the 2006 Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction and was selected as Editor’s Choice by the New York Times. Panning’s publications also include the story collection The Price of Eggs (Coffeehouse Press, 1992), as well as nonfiction. Four of her essays were recognized by the Best American Essays series. She teaches at SUNY Brockport.

We met a few years ago at Southern Illinois University’s (SIUC) Devil’s Kitchen Literary Festival in 2008. I was an MFA student, and Anne was a visiting writer reading from Super America. My adviser, Beth Lordan, who invited Panning to Carbondale, told us the formula for success was simple: “Just do what Panning does.” Between sessions, Panning gave me a piece of advice that’s always stuck with me. “It’s just work,” she said. “A writer sits down and does it, or they don’t.”

On the eve of Butter’s publication, Anne and I chatted via Facebook and email about mothers, missing persons, and dairy dispensers.

Interview

Melissa Scholes Young: When we met at SIUC’s Devil’s Kitchen Festival, another writer claimed that writing simply required listening to her characters and channeling their voices. You disagreed. You said writing is just work – and you threw in an f-bomb for emphasis. Is it still work? Does the work come any easier with success?

Anne Panning: Well, I suppose there’s a bit of the Protestant work ethic alive in me, having grown up in the Midwest in a very poor working class family. I don’t mean to suggest that there’s no pleasure in writing for me; there is. But the best thing I can liken it to is running. Often while you’re running, you just want to stop, walk, do something else that’s easier. But there’s nothing better than the feeling of having run. It’s exhilarating. I feel the same way about writing. I need to do it, am a wreck when I don’t do it, but it isn’t magic or easy for me as I do it. I labor for my pages, and I fight through massive distraction to do what I do. I guess with writing each book it does get a little easier, though I’m uncomfortable using “easy” and “writing” in the same sentence.

On your blog, you tell the story of how the cover of Butter came to be. You wrote about your connection with the artist whose piece became the inspiration. What first drew you to her work? Besides the obvious connection [to butter], why do you think it best represents the novel?

On your blog, you tell the story of how the cover of Butter came to be. You wrote about your connection with the artist whose piece became the inspiration. What first drew you to her work? Besides the obvious connection [to butter], why do you think it best represents the novel?

I had a very clear image in my mind for the cover of Butter. I wanted a retro feel, sort of like the old butter boxes my grandpa used at his creamery, with bright red wavy letters and bold saturated colors. The problem was, I didn’t want the cover to be too literal so that people would mistake it for a supermarket ad for butter. But then one day I came across Jana Bouc’s work online. She has a painting called “Butter and Tea, Surface Quality Study #2,” and I fell in love with it. It was exactly what I had in mind, partly for its rich, Edward Hopper-like light and mood, but also because I wanted the cover art to suggest some kind of narrative beyond the image of butter, which hers did so perfectly. I thought her painting represented the comfort, but also the decadent, over-much quality of butter. It felt as if someone had just left the scene, inviting readers to come in and see what just happened.

Butter is told from Iris’s eleven-year-old point of view. It instantly reminds me of Ellen Foster, not in content but form, especially in how the innocence and malice are juxtaposed. Did Iris’s voice come first in the writing?

First of all, thank you, thank you, for mentioning Kaye Gibbons’s Ellen Foster, because that book remains for me a true model. I knew it was dangerous to try and write in a first-person, 11-year-old point of view, but I also knew there had to be a way to ride that line between “innocence and malice,” as you say. It’s tricky. I had originally (and a bit stupidly) written the book in present tense, but with such a young narrator it was simply too much. With the semi-reflective past tense, it seemed a bit safer. I wanted her to be smart but not precocious, strong but not daring. I wanted her to have a clean narrative voice, not one prone to editorializing or sarcasm.

There is such tension between Iris and Adam [Iris’s brother] throughout. Every time Adam entered a scene, I braced myself. Yet there are also these very real sibling moments between them that were endearing. How does Adam’s character contributes to Iris’s coming of age?

I think Adam scares the hell out of Iris, but not for the same reasons that he scares readers. I think Iris’s whole problem is that she never feels as if she is enough. Even though they already have her as their daughter, Iris’s parents not only keep trying to have their own biological child, they also adopt Adam. He is jaded and cruel, but also vulnerable and scared in his own way. I worked very hard to be subtle with Adam, to rely on inference and indirection as much as possible. I think Adam forces Iris to grow up far too quickly and, as a result, he also manages to create a wedge between her and her mother just when she needs her [mother] the most.

Okay, we’re mothers, Anne, so we have to talk about Iris’s mother. She’s estranged as a mother – lost in her writing, unfulfilled in her marriage. She struggles in this stifling small town with her own lack of purpose. She’s aware of feminism, but she doesn’t have any of the tools to reap its benefits. Can you tell me about the process of writing Iris’s mother?

Okay, we’re mothers, Anne, so we have to talk about Iris’s mother. She’s estranged as a mother – lost in her writing, unfulfilled in her marriage. She struggles in this stifling small town with her own lack of purpose. She’s aware of feminism, but she doesn’t have any of the tools to reap its benefits. Can you tell me about the process of writing Iris’s mother?

I keep thinking of that article in the book Creating Fiction, “Sympathy for the Devil” – how you have to give even the “bad guys” redeemable qualities in fiction so readers can find a reason to like them. I think the fact that Iris’s mother continues to suffer miscarriage after miscarriage lends a certain sympathetic air to her. I also think her life, although not terrible by any stretch, sucks. She’s trapped in a place where people judge harshly and quickly, and her writing, that typewriter, seems like her only way out. Also, though she does horrible things like run off with really young guys, she never completely disregards her kids, but leaves them in the care of her mother. As a child, I was shuffled off to my grandparents when things were difficult for my parents, and I think Iris’s grandma is her safety net, just like my Grandma Lucille was mine.

The prose in Butter often has a dream-like quality. Each chapter begins with flashbulb memories. Are you playing with memory? Time? What effect did you want the memory passages to have on the story as a whole?

I actually added those memory bits to each chapter long after I completed the book because, for some reason, I felt the novel needed a deeper frame that relied more on impressionistic images and moments. The memories are not really presented chronologically; I wanted them to run counter to the book’s linear progression, much the way our own memories, in scattershot fashion, continue to shape our everyday, forward-moving lives. I like to play with form, and since this is my first novel, I wanted something to add texture, and play just a bit. The book seemed too spare without it.

What led to your decision to publish with Switchgrass Books?

Because publishing is changing so much almost daily, I really thought long and hard about the best place for Butter. It’s a “quiet” book, as the publishing industry would say, but I also knew that the book was ready to go out. One day I was researching presses online and found that Switchgrass Books was looking for novels set in the Midwest. I read a few of their titles, decided that Butter was as über-Midwestern as you could get, and sent it to them. The editor-in-chief, Mark Heineke, contacted me shortly thereafter with an offer to publish it.

Because publishing is changing so much almost daily, I really thought long and hard about the best place for Butter. It’s a “quiet” book, as the publishing industry would say, but I also knew that the book was ready to go out. One day I was researching presses online and found that Switchgrass Books was looking for novels set in the Midwest. I read a few of their titles, decided that Butter was as über-Midwestern as you could get, and sent it to them. The editor-in-chief, Mark Heineke, contacted me shortly thereafter with an offer to publish it.

What do you see as the benefits of working with smaller presses?

I could go on and on about the benefits of small presses. For one, my very first book, published in 1992, is still in print! And with Switchgrass, as well as with University of Georgia Press, I was allowed to have a say in the cover design – something very rare when dealing with commercial presses. There’s also a great deal of personal interaction between editor and writer that I find extremely rewarding and comforting. And these days, I think it’s much less important that you publish with commercial presses because of the democratic nature of book promotion. Facebook, Twitter, websites, Amazon, etc., all allow a writer to get her work out to the reading public. And contrary to popular belief, you do not necessarily suffer a lack of reviews in important places (the New York Times Book Review, for example) with small presses. Word gets out.

You seem to be having a lot of fun with your promotion for Butter. I’m thinking of the various butter delivery systems that you’ve been showcasing on Facebook. Can you share your favorite butter-themed product so far and talk a little about the work of promotion?

Squeeze-n-Art

I could’ve never guessed how much fun I would have with all the butter-related gizmos I’ve come across with this book. I have a device called a Squeeze-n-Art that houses a whole stick of butter with various attachments for squeezing out various shapes of butter: star, ribbon, zigzag. I also ordered Butter t-shirts after a friend of mine said how much she loved the cover, and that she wanted a t-shirt of it. Before I knew it, I sold 50 of them on Facebook, and we’re still going. There is nothing like seeing someone wearing a t-shirt with your book cover on it. Nothing! Facebook has been a huge tool for me in terms of promoting my book.

In addition to using Facebook, you blog and use blogging as a teaching tool. I especially enjoyed your pedagogy discussion about using blogs in the creative writing classroom. What do you see as the value of community and public space in workshopping one’s work?

I think it connects student writers to the real world in ways that can be wonderful, difficult, risky, and liberating. Too often in workshops students write for an insulated, academic audience. By taking the step out into the public, they can (a) get instant feedback , (b) learn that there are “real” readers out there, (c) discover the temporary nature of writing online, and (d) take risks. The semester that I required students to use blogs was probably the most challenging of my academic career so far, but that’s not to say I wouldn’t do it again. Their writing changed, grew. It engaged with outside concerns more, and students reached far beyond themselves.

Who are you currently reading?

The novel Heft by Liz Moore. (On a Nook I just purchased, God help me!)

Can you share with us a preview of what’s next?

I just completed a memoir called Dragonfly Notes: A Memoir of Motherhood & Loss. Right after I returned from a sabbatical leave spent in Vietnam, my mother died suddenly during a routine operation. The book is not so much about grief as it is about the surprising things I learned about her life after she died; the intersections and similarities I never knew we shared. It needs a few more go-rounds of revision before I send it to my agent.

After that, I can’t wait to write my first missing-person novel, set on an allegedly haunted golf course in Minnesota. I went golfing this summer for the very first time as research.

Further Links and Resources:

Further Links and Resources:

- Listen to Panning read from Butter.

- Read a short essay by Panning in Brevity.

- Check out the author’s own blog.