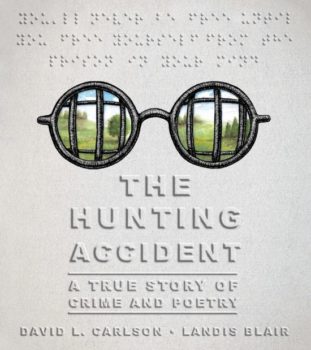

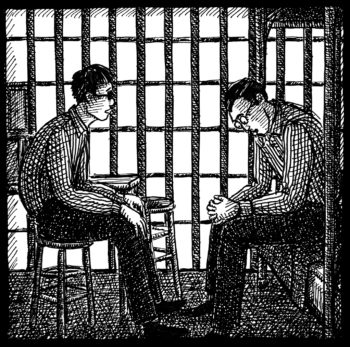

David L. Carlson and Landis Blair’s graphic novel The Hunting Accident (First Second Books) is a true crime story that incorporates literary history, philosophy, and poetry to tell the tale of Matt Rizzo, who was blinded when he held up a corner shop on the west side of Chicago. He was blinded when he was shot in the face by the store owner, then arrested, summarily tried, and jailed at Joliet State Prison—locked in a cell with one of the perpetrators of the “Crime of the Century,” Nathan Leopold. Leopold took Rizzo under his wing; a gifted polyglot, Leopold learned how to read Braille so that he could in turn teach Matt to read and guide him through Virgil, Dante, and other classic works. Leopold was in part acting out of boredom and in part currying favor to speed his path to parole, but there is no question he changed Matt Rizzo’s life. When Rizzo was released from prison, he began writing and eventually married. He lied to his wife—and in turn his son, Charlie, the other central character in the story—saying that he was blinded in a hunting accident. His story unraveled when his mother-in-law intercepted a letter from Leopold in prison, and his wife left him, taking Charlie with her.

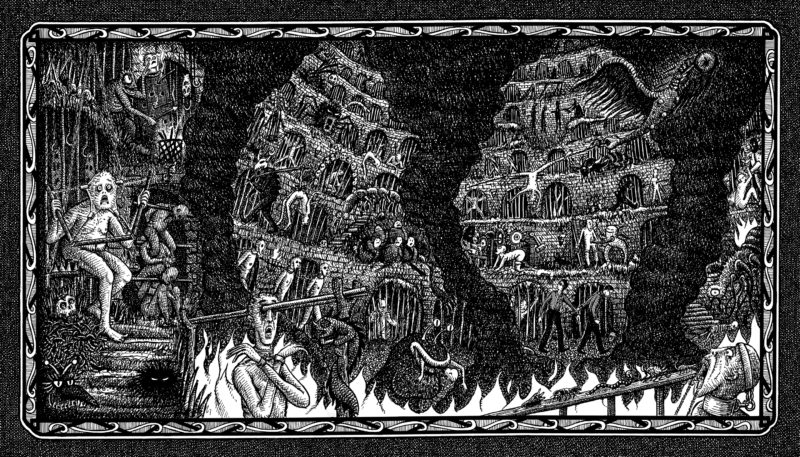

Some years later, Charlie’s mother died of cancer, and he was remanded to his father’s custody. Still under the impression that his father was blinded in a hunting accident, Carlson and Blair’s graphic novel tells the story of how Charlie came to learn what really happened to his father—and why the great poets loomed so large in his imagination. A story of fathers and sons, of betrayal and redemption, The Hunting Accident is a handsome tome of a book that’s been lauded for the interplay of text and image—and in pivotal moments in the story, Blair’s elegant and intricate crosshatched illustrations supersede language, leading us through the moments when Matt was blinded, when Charlie learned about what happened to his father, and—most delightfully—when Matt helped stage a shadow puppet performance of Plato’s Cave allegory for an impromptu hobo theater.

I first encountered Landis Blair in 2016, right around the time that First Second Books contracted The Hunting Accident. He invited me to visit the studio where he spent six days a week over two and a half years working on the illustrations—the walls of the studio are covered with the original drawings. I was dazzled. Soon I read the Kickstarter version of The Hunting Accident and was incredibly moved by the depictions of Matt and Charlie Rizzo as well as Nathan Leopold, who serves by turns as hero and villain throughout the story. And as a writer I was struck by the ways in which image and text alternately wove together and gave way to one another. I spoke with Landis about the process of illustrating The Hunting Accident—recently featured in the New York Times Books section—and asked him further about his literary influences, as well as his Choose-Your-Own-Adventure comic adaptation of Kafka’s The Trial.

Interview:

Jennifer Solheim: You were brought onto The Hunting Accident early in the process of turning the story into a graphic novel, but the writer, David Carlson, had already commissioned both a play and a screenplay, and if I remember correctly, you were originally working from the screenplay, is that right? How did the collaboration between you and David proceed from there?

Landis Blair: When David brought me onto The Hunting Accident, he had already written a screenplay of the story in addition to commissioning a playwright to write a separate stage play telling the story from a different perspective. When I started David gave me the screenplay, and I read through it and spent a couple months converting that screenplay into thumbnails for a graphic novel. During this process he encouraged me to add my own perspective and ideas on the story and to let my imagination take over. After the thumbnails, David and I printed them all out to the scale of the book and tacked them onto large pieces of foam core and then spent the next two months reading through and hashing out the story, improving, adding, removing, and rearranging until we were satisfied. It was five months from when I started that I actually began to pencil and ink some of the final pages for the book.

Landis Blair: When David brought me onto The Hunting Accident, he had already written a screenplay of the story in addition to commissioning a playwright to write a separate stage play telling the story from a different perspective. When I started David gave me the screenplay, and I read through it and spent a couple months converting that screenplay into thumbnails for a graphic novel. During this process he encouraged me to add my own perspective and ideas on the story and to let my imagination take over. After the thumbnails, David and I printed them all out to the scale of the book and tacked them onto large pieces of foam core and then spent the next two months reading through and hashing out the story, improving, adding, removing, and rearranging until we were satisfied. It was five months from when I started that I actually began to pencil and ink some of the final pages for the book.

Taking up the old adage that we write from what we know, in writing a story set in 1920s, ’30s, and ’60s Chicago, Joliet State Prison in the 1930s and ’40s, as well as in the literary imaginings of Matt Rizzo and Nathan Leopold, how did your own background and experience contribute to the story?

In large part I feel like my background and experiences did not lend themselves to much assistance with the story. However, thematically, with the darkness—both literal in the case of blindness as well as figurative in the setting of the prison—there was something I could relate to in the claustrophobia in thought and emotion that comes with feeling trapped within that darkness. On a more practical level, I think my crosshatched drawing style was what contributed most to the story given that I’ve long been drawn to and inspired by black and white line work that is reminiscent of an older time. Given that I was comfortable thinking and working in that style, or rather that vague vintage aura, the pages for The Hunting Accident seem genuine despite my actual ignorance of the time period and setting.

You listened to music when you were completing the pencil drawings for The Hunting Accident, but when you were inking the pencils you often listened to audio books—particularly Dickens, right? What are the different levels of thought that go into creating panels in a graphic novel? How do the pencils as compared to inking function in terms of narrative?

For me, the pencils were the hardest and most unenjoyable part of this entire process. The actual work happens in laying down the foundation for each page so if the foundation is wrong, the entire page can fall apart. This being said, despite it taking less time than the inking, the pencils required my full attention and thus having music in the background—or silence—was all that my brain could handle. Conversely, despite the inking being the most labor intensive part of the process, the way I work with crosshatching feels to me for the most part like I am filling in a coloring book. As such, I was able to spend those many hours listening to audiobooks while my hand worked mechanically on the pages. Dickens was indeed a favorite, most notably when I was inking eight solid pages depicting Hell in Dante’s Inferno and I listened to David Copperfield to keep me going.

Did David Copperfield and the Inferno speak to each other in any way, or was it because Dickens’s universe is so removed from Dante’s that they worked well for you? Or something else altogether? Could you also describe the process of creating panels in graphic novels (pencils vs. inking)?

I don’t think I really made a connection at the time between Dante’s Inferno and David Copperfield. It was more along the lines of having this long complex narrative playing in my head to pass the time. Perhaps though, in retrospect, it needed to be completely removed from the intensity of the pages I was inking otherwise it may have taken a lot longer or the drawings may have come out much worse. In answering your question, though, I suppose one could make the argument that the oppressive cycle of Victorian poverty that Dickens is a master of expressing is connected to the circles of Hell that Dante depicts where the punishment is a combination of suffering and monotony. Perhaps some of that subconsciously seeped into the drawings in that the creation of the pages was monotonous and I was in some sense imprisoned at my desk at this task that didn’t seem like it would end. But in the end, Dickens saw me through.

Different comic illustrators work in different ways, but as far as my personal process goes, I usually break it down into five main stages. The first stage is sketching out small thumbnails of the pages. My thumbnails are usually only a couple of inches wide, but the main point of these drawings is to figure out the overall composition and feeling of a page. I need to make sure that it spatially works, so I often do a number of sketches before arriving at my finished thumbnail. This is the most creative part of the process, as anything can happen and it is easy to try different ideas until I am happy with them. After that, my second stage is to do any sketches required to figure out the characters or certain elements on the page. The bulk of this work is done all at once at the beginning, just trying to figure the feel and style of a book, but as unique elements emerge along the way I do these kind of sketches throughout. In the Dante’s Inferno pages, for example, I did a number of sketches of fire beforehand to figure out how I could best show the flames, given the constraints of the page and the constraints of my abilities. My third stage is converting the thumbnail drawings to full-scale pencil drawings. This is the hardest part for me as it is when I believe the actual creation process takes place since this is the stage where a blank sheet of paper has to end up with a framework that holds up the ink drawing. After penciling the page, my fourth stage is outlining the pencil drawing with ink. And my final stage is inking, where essentially I fill in the entire drawing with crosshatching in order to build up the tones on the page. This last stage takes the longest, but it is by far the easiest.

It’s interesting: at New York ComicCon, the panel of which you and David were part was titled “Illustrated Narrative.” But that’s something of a misnomer—it’s difficult to encapsulate how language and image work together in graphic novels, because they are part and parcel of one another in telling the story, and often the images supersede the text in storytelling. For example, the passages of The Hunting Accident that feature shadow puppet plays of Dante’s Inferno and Plato’s Cave that might be best described as “narrative illustration” because there is little to no text involved—yet multiple stories fully realized in these pages. In terms of storytelling process, what was the give and take between you and David?

Having never collaborated on a project of this scale with someone before, I was initially wary and didn’t know what to expect. I quickly, though, began to realize just how much David wanted this project to be a true collaboration and not just me illustrating his story. As I accepted this, we entered into a rather intense but good back and forth over the next few years. All through the process we would discuss the upcoming pages I was to pencil and ink and we allowed ourselves to let the story start telling itself by using our own curiosity, interests, and fears as guideposts. We would frequently have long discussions about a topic that might not initially seem relevant to the story but then ultimately somehow changed and improved what we were doing with the storytelling. After David and I began to trust one another in this process we each began contributing and editing the story; sometimes David would want to insert an idea and sometimes it would be me. The important thing was that we talked about it together and that any idea was worth at least playing around with before making a final decision. It was intriguing to see how we began to know what to ask of the other that we ourselves couldn’t do. David cut out a lot of text after seeing my illustrations, and often I would ask him to add a line of dialogue or exposition in order to bridge a gap in the story that would take too long or be too complicated for me to illustrate. In the end, while the story is indeed David’s, both of our fingerprints are smeared all over it.

Having never collaborated on a project of this scale with someone before, I was initially wary and didn’t know what to expect. I quickly, though, began to realize just how much David wanted this project to be a true collaboration and not just me illustrating his story. As I accepted this, we entered into a rather intense but good back and forth over the next few years. All through the process we would discuss the upcoming pages I was to pencil and ink and we allowed ourselves to let the story start telling itself by using our own curiosity, interests, and fears as guideposts. We would frequently have long discussions about a topic that might not initially seem relevant to the story but then ultimately somehow changed and improved what we were doing with the storytelling. After David and I began to trust one another in this process we each began contributing and editing the story; sometimes David would want to insert an idea and sometimes it would be me. The important thing was that we talked about it together and that any idea was worth at least playing around with before making a final decision. It was intriguing to see how we began to know what to ask of the other that we ourselves couldn’t do. David cut out a lot of text after seeing my illustrations, and often I would ask him to add a line of dialogue or exposition in order to bridge a gap in the story that would take too long or be too complicated for me to illustrate. In the end, while the story is indeed David’s, both of our fingerprints are smeared all over it.

You published a Choose-Your-Own-Adventure comic based on Kafka’s The Trial a few years ago. How did you go about adapting Kafka in this way?

Initially the Choose-Your-Own-Adventure format was a practical solution I came up with to the problem of being asked to adapt the entirety of The Trial in only sixteen pages of comics. However, the more I thought about the idea, the more I realized just how appropriate it was given the cyclical nature of Kafka’s work and the nightmarish feeling of the world closing in on Josef K. with inescapable monotony. Additionally, I read somewhere that Kafka himself did not specify the order of the chapters in The Trial and that scholars have had to give their best guess as to their order. Realizing this, it was only a matter of trying to distill the book down to its crucial parts and then coming up with ways to link all those parts in a manner that was not chronologically specific. It basically became a visual puzzle and while it was extremely frustrating at times—I found myself wishing I had fifty pages instead of sixteen to work with—I enjoyed the challenge of having to make decisions about which sections to include. The format also freed me to insert my own dialogue and in order to help bridge the truncated format and transitions between pages. So while I added some things and modified others, my goal and hope was that in reading the final comic someone would feel at the very least like they were believably in Kafka’s world.

What nongraphic fiction has influenced your work the most?

Perhaps the best way I can answer this question is to share which nongraphic fiction works I’ve read that leave me feeling most inspired and wishing that some day I would be skilled enough to illustrate: Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, Leo Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilych, Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, and Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane.

What graphic novels would you recommend for fiction writers?

Habibi by Craig Thompson juggles many layers of narrative and religious themes while dazzling the eye with complex beautiful drawings throughout. From Hell by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell is a story that delves into a level of complexity and intricacy that requires the full attention of the reader and pays off, all the while held together by evocative pen-and-ink crosshatched drawings. Building Stories by Chris Ware is impossible to describe and needs to be seen for itself, but I would argue that this graphic novel is pure narrative that’s driven by the reader. The Salon by Nick Bertozzi is half art history, half fantastical monster, and fully mesmerizing with how the drawings and coloring carry the story. And lastly, Sailor Twain by Mark Siegel weaves a rich American mythological story about a writer and his struggle to be creative again.