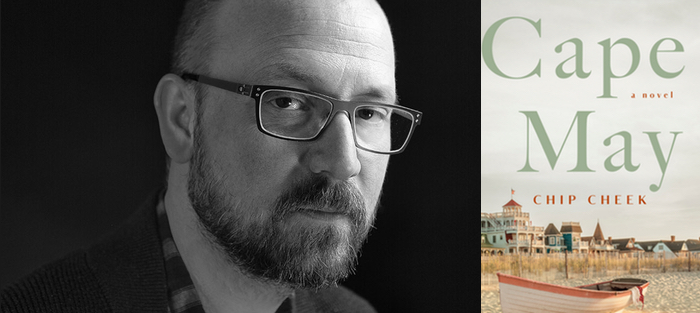

Even though it’s set in 1957 during the gray offseason in a seaside resort town, Chip Cheek’s debut novel, Cape May (Celadon Books), is going to make a lot of “must read” lists this summer. Its dangerously young newlywed protagonists from Georgia—farmer’s son Henry and businessman’s daughter Effie—take their honeymoon at a relative’s house in mostly-shuttered Cape May at the southern end of New Jersey, where Effie had spent vacation time as a child. There, they lose their innocence in a sudden, staggering crash that catches the reader like a giant undertow and pulls them into a cold, uncertain future.

The occasion of Henry and Effie’s fall from freshly-wedded grace is one of the few houses in town not shut up for the offseason. In it they find Clara, who had lorded over Effie years before when they first met, and who is now a debauched Yankee socialite married to an older, absentee husband. Along for Clara’s ride is her lover, the wealthy and raffish would-be writer Max, and Max’s waiflike half-sister, Alma. Despite Effie’s reservations about getting too close to Clara, the couple falls into their social circle and emotional spell and ends up spending most of their time in Clara’s orbit.

There’s drinking—lots of it—and a specter of infidelity that suffuses the novel from the moment Clara and Max show up. The metaphor of a slow-motion train wreck is overused, but it’s apt here. I read Cape May knowing that Henry and Effie’s honeymoon was doomed, yet I wanted to stare at and soak in all the logistical details of the betrayal it examines up close. I couldn’t not watch even as characters plunged themselves into situations that couldn’t possibly lead anywhere good. By the end of the novel, when the undertow kicks in, the newlyweds’ story is a tragedy that sticks in the mind.

Cape May is also a very sexy book, which is why you’ll find it on beaches this summer when people’s winter clothes are put away. Chip and I talked in the calm before the storm of his novel’s release date at the end of April.

Interview:

Steven Wingate: Cape May has a fascinating birth story. You mentioned to me how the deal for it came together right around the time you became a father.

Chip Cheek: First of all, let’s acknowledge and appreciate what you did there: “birth” story. Nicely done. But, yes! Those were the most insane few months of my life. When Katie and I learned we were going to have a baby, I’d been spinning my wheels for nearly two years revising and rewriting the novel, and I had only three good chapters to show for it. I was beginning to think I’d never finish the rest, that I lacked whatever gene other writers had that allowed them to finish books.

But then we got the baby news, and underneath my excitement I saw a potentially bleak future unspooling before me, in which I never finish the book, and then I have a baby and can never write again, and then resentment sets in—etcetera, etcetera. Of course, that’s ridiculous—I mean, I have a baby now, and she makes me incredibly happy, and I intend to write many more books—but still, that vision terrified me. So I raced to finish the book before the due date, like my life depended on it, and I finished it a month early. I gave it to my writing group, met with them a few weeks later, and four days after that meeting, the baby arrived. Another month or so went by before I could come out of the new-baby fog long enough to make a few edits and submit it to an agent. I knew I wanted to send it to one agent in particular, Katherine Fausset, whom I’d long admired, and whom I’d met a handful of times at writing conferences, so I sent it to her and no one else, thinking I’d send it out to more agents later.

But miraculously, she got back to me after a few days and said she couldn’t put the book down. I think it was just another month or so after that when we sent the book out, and it sold to Celadon in less than twenty-four hours, in a preempt, and then went on to sell to publishers in six other countries in the weeks following. All this time, I was in a prolonged state of shock. I think I’m still in shock, honestly. I remember quietly freaking out in the dark while rocking the baby at two, three in the morning. Katie was on maternity leave, and I was working from home. We were both sleep-deprived, terrified, and weepy all the time. We went on these long, stunned walks. It was fall, and we were in Massachusetts, and the leaves were brilliant. I’ll never forget that time.

In a publicity interview for your publisher, you talk about the process of coming to Cape May after trying to write other novels and noticing that you always got sidetracked by love stories. Can you talk about the moment you officially made the switch to this story? What was the first thing you did once you decided this novel was “it”?

Before Cape May, I was working on this dark, violent novel set in Georgia in the twenties. But again and again I’d get sidetracked, especially by these naughty little tangents—midnight meetings in the woods, skinny-dipping, things like that—which I’d then have to scrap because they had nothing to do with the central action of the novel. I was clearly more interested in sex than death. So finally, for reasons that made sense at the time, I decided to marry my point-of-view character, Henry, to a then relatively minor character, Effie, and send them on a honeymoon. This was the summer after Katie and I got married—2014—so I guess marriage was looming in my mind. I chose Cape May because a good writer friend of mine, Lizzie Stark, had a house there, where we and other friends used to go in the off-season for writing retreats, and I came to associate the place with this gloomy, alluring atmosphere. Within two or three days of starting the honeymoon storyline, I’d written about fifty pages—an incredible output for me—and I didn’t want to stop. It was only then that I realized I’d started a new novel, and I just kept going. I finished the first draft in two months, almost to the day. I’d never written anything so quickly or obsessively in my life.

Advance buzz for this novel has included a bit of talk about The Great Gatsby—because of the decadence, I suppose. But another book strikes me as more apt: Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road, which is set about the same time and also concern a troubled marriage. What books are hidden in the shadows and corners of your novel?

I love this question. I’m a big fan of The Great Gatsby, but I’m not sure I thought about it even once while I was writing the book. Maybe that’s not possible—it must have exerted some kind of influence—but if so I don’t remember. I do remember thinking about Revolutionary Road in a passing way once I knew the time period for the novel, but I never went back to it.

I love this question. I’m a big fan of The Great Gatsby, but I’m not sure I thought about it even once while I was writing the book. Maybe that’s not possible—it must have exerted some kind of influence—but if so I don’t remember. I do remember thinking about Revolutionary Road in a passing way once I knew the time period for the novel, but I never went back to it.

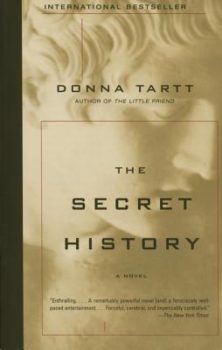

The book that was probably most present in my mind while I was writing was Donna Tartt’s The Secret History, even though my book has very little in common with it. It’s in the thrill of meeting this mysterious group of people; it’s in the rarefied atmosphere. To get myself in the right mindset to work, I’d think: Imagine if James Salter wrote The Secret History. And there I’d be. Speaking of Salter, I’d long been a fan of Light Years, but I’d never read A Sport and a Pastime, his erotic novel, and since I was writing a book that also focused very explicitly on sex, I purposefully did not read it until after I’d finished the first draft, because I was sure I would throw my own book in the trash if I did. The same goes for Ian McEwan’s On Chesil Beach: I didn’t read it until after I’d finished my own honeymoon novel. And I’m glad in both cases that I waited.

Cape May is set in the late 1950s, an era often affiliated today with a national loss of innocence. Why is that era an important time to be setting a novel now—particularly a novel about lost innocence within a marriage?

I wish I could claim to be as intentional as this question makes me seem, but the truth is there was nothing in particular I was trying to convey about the 1950s—it’s just the era that I thought would be the most meaningful fit for the action in the novel. I didn’t decide on the period until long after I’d finished the first draft. As I mentioned earlier, the novel I was working on before Cape May, the one Cape May grew out of, was set in the twenties, and the first chapters I wrote were set then.

But once I realized I wasn’t tethered to that period anymore, I experimented with several different eras over the course of writing the first draft. For a few chapters, it was set during World War II, and Henry was about to get shipped away to the Pacific. There was a chapter or two set in the sixties. I even, very briefly, toyed with the present day. I struggled with this question for months, in fact, after I’d finished the first draft and was trying to decide how to revise it. Ultimately I landed on the fifties, because if it was set too much earlier the action wouldn’t feel plausible, and if it was set too much later the action would lose its charge. So the story came first, and I picked the time period that I thought best fit it, and then I revised it to make it seem like that’s what I’d intended all along. It’s the magic of revision!

Toward the end, Effie has a line that struck me: “[W]e will have a fortune. We will be secure, for our children. Everything else is bullshit.” This strikes me as a specific kind of lost innocence that unfolds on a personal level for Henry and Effie and on a sociological level for America. What’s rolling around behind those lines for you?

Yes, a kind of loss of innocence, or naiveté, is happening there. Effie is a mix of the tough, no-nonsense Southern women I grew up with—my mother, my aunts, some of my cousins. They may have their sentimental, even maudlin sides, but at their core they are practical, and to a significant degree marriage is transactional for them. Romance is all well and good, they might say, but more importantly, will this man provide for me and help me raise—to use Effie’s phrase—“sensible children”? When the novel is set, Effie is still young and naïve about a great many things, including love, but she is going to grow up to be tough as nails, and that side of her begins to emerge by the end of the novel. In fact, it’s there all along, in the first chapters, whenever she and Henry talk explicitly about their marriage or their lives together. It’s there when she says, about Max, the novel’s dilettante playboy, “But—I mean—he can get a job.”

You worked for years at Grub Street in Boston, one of America’s great community writing centers. How did that experience prepare you for this moment both as a writer (someone who sits down alone and works) and as an author (someone who has to get out in the world and talk about their work)?

I owe Grub Street just about everything; I wouldn’t be where I am now without that community. After the baby, Katie and I moved to the L.A. area, to be closer to Katie’s family—maybe the toughest decision of our lives—and the thing I miss most about Boston is Grub Street. It is by far the most welcoming, encouraging, disciplined, tight-knit, utterly talented but also utterly unpretentious set of writers I have ever been a part of or even heard of. I taught fiction at Grub Street for many years, and then I worked on the staff, as the head instructor, in charge of hiring new instructors and coming up with new programs. I met many of my closest friends there, fellow teachers and staff members—all serious writers—and those people shaped who I am now, and continue to do so from afar. They taught me and challenged me as a writer, and they also showed me how to be.

I owe Grub Street just about everything; I wouldn’t be where I am now without that community. After the baby, Katie and I moved to the L.A. area, to be closer to Katie’s family—maybe the toughest decision of our lives—and the thing I miss most about Boston is Grub Street. It is by far the most welcoming, encouraging, disciplined, tight-knit, utterly talented but also utterly unpretentious set of writers I have ever been a part of or even heard of. I taught fiction at Grub Street for many years, and then I worked on the staff, as the head instructor, in charge of hiring new instructors and coming up with new programs. I met many of my closest friends there, fellow teachers and staff members—all serious writers—and those people shaped who I am now, and continue to do so from afar. They taught me and challenged me as a writer, and they also showed me how to be.

Christopher Castellani, who’s been the artistic director at Grub Street for most of its existence, and who has been a mentor to me over the years (and who, I should add, is the author of the absolutely beautiful novel Leading Men, which came out earlier this year), would often say that Grub Street had a “strict no-diva policy.” And he would say, “We take our writing seriously; ourselves, not so much.” That was one of Grub Street’s unofficial mottos, actually. I’m not sure if Chris coined it, but he certainly embodied it, and I’ve tried to conduct myself along those lines. I think a community is what most young writers are hungry for—why so many people apply to MFA programs and writers’ conferences and so forth. I mean, we want access, we want to get our work out into the world, but it’s more than that; the desire to become a writer is more than a professional goal, it’s a desire for a certain way of living in the world. The work itself is solitary, and most of us come to it alone—we weren’t born into the literary world—and so we’re eager to find a way into that world, to find people we can talk to, people to relate and commiserate with. Grub Street gave me that.

What’s next for you? You’ve moved from one coast to the other, published a much-anticipated novel, become a father. That’s a lot of change in very little time. In addition to the usual question of “What are you writing next?” I’m also curious about how all this change has altered your writing practice overall—your approach to your craft, your work habits, etc.

The short answer is that all this change has completely destroyed my writing practice—for the time being. With any one of these big life changes there’d be a period of adjustment, but for all of them to happen one after the other … it’s been a lot to get used to. I’m not complaining—I wouldn’t trade any of it—but still. We’re far from settled here, we don’t even have our own place yet, and I feel unmoored and at loose ends with my work. I know some writers who can write anywhere and in whatever state their lives are in, people who are just compelled to write and will do so no matter what, but I am not one of those writers. I’m a creature of habit; I’m devoted to process and routine. I live by Flaubert’s maxim—I’m paraphrasing here—to be regular and orderly in your life so that you can be wild in your work, and my life has been anything but regular and orderly these days. So aside from a few brief bursts of productivity here and there, I have written almost nothing since finishing Cape May. I’m a determined optimist, though, and we are slowly but surely getting our new lives in order, and I’ll get back to productivity eventually. But as far as what’s next for me, I’m not really sure. Which I guess is exciting?