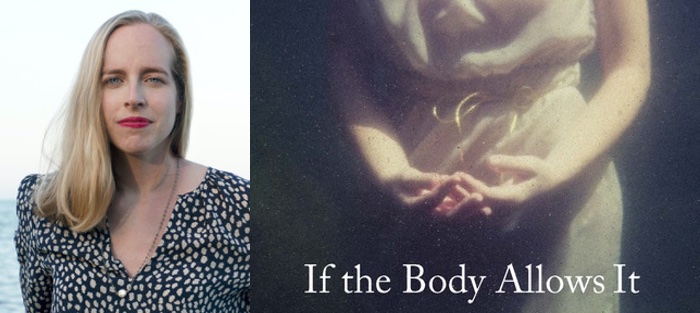

I met Megan Cummins while I was reading manuscripts from the slush pile at A Public Space, the magazine where Megan is now Managing Editor. Megan’s kindness, intelligence, and devotion to other writers were immediately evident, and so it’s an enormous pleasure to see her debut story collection come into the world.

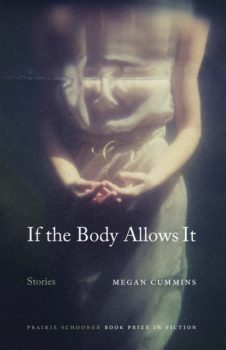

Winner of the 2019 Prairie Schooner Book Prize, If the Body Allows It feels unusually unified; it uses installments in the life of Marie, a young woman struggling with auto-immune disease, to frame stories that drive straight into experiences of addiction, betrayal, illness and recovery, and the difficulties and redemptions of loving other people.

Megan and I conducted this conversation over email, which allowed for a satisfying, considered progression during a time that feels both stagnant and hectic. We were both in Brooklyn, and so the contact felt both intimate and remote—we could almost hear the same sirens but could have been writing to each other from anywhere.

In addition to being managing editor at A Public Space, Megan Cummins holds the same position at A Public Space Books. Her work has been published in Ninth Letter, One Teen Story, Guernica, and Electric Literature.

Interview:

Alexander Tilney: So many of these stories involve people who are anchored into their bodies, willingly or unwillingly, often because they’re contending with illness or addiction. Before we talk about what that means for them, I want to ask about whether your activity of writing, sitting down and working on stories, has a physical aspect or practice. (The sensation of pen on paper, for example.) Or do you try to block out physical experience to get into the dream of the narrative?

Megan Cummins: I love thinking about this question, about what to do with one’s body while writing. We hear funny things, like tying oneself to the chair. To be honest, while the body is one of the central concerns of my everyday life, it’s of little concern in my writing life. I just do what it wants. I snack. Sometimes, an idea (not even necessarily a good one) makes me stand up and walk to the other room, and I do that, as though it was something scary and I had to get away. And then I sit back down. I switch to handwriting often in the middle of drafting, or go back and forth. I also think about “flow state” a lot, when everything else fades away. Sometimes I think this has never once happened to me, but I think it must occasionally. There’s no way I would’ve ever finished a book otherwise, given all the snacking and standing up and walking around.

I also want to know about how your work as the managing editor of A Public Space influences your writing. Does the reading and refining of each issue inform the work you’re doing at any given time? Do you turn to the work in the magazine for inspiration, or do you maybe have to block those voices out to try to hear your own writing voice?

I also want to know about how your work as the managing editor of A Public Space influences your writing. Does the reading and refining of each issue inform the work you’re doing at any given time? Do you turn to the work in the magazine for inspiration, or do you maybe have to block those voices out to try to hear your own writing voice?

I think working for a literary magazine and book publisher has had an enormous influence on my writing, probably in ways I haven’t really realized. When I’m writing, I don’t think about my work as an editor. I allow myself to be as messy as I need to be. But when I’m revising my own work, I use the same eye—when I edit, I try to learn the writer’s style and figure out their intentions, and how to help them realize their vision. I ask myself the same questions: why this detail, why this choice? Where did I end up? I feel the best about my writing when I end up somewhere I hadn’t planned to be. The magazine and books we publish are always inspiring to me, and they remind me to stretch as far as I can in my writing.

The structure of the book is so effective, with Marie’s story divided into parts of the body (Heart, Eyes, Lungs, etc.), with each part marking sections of stand-alone stories. This creates such effective continuity and a strong unified voice through the collection. Was that your intention from the beginning, or did the structure emerge as you were finishing the stories and ordering them for the book?

At first, I was just writing stories, not a book. And while I knew they were linked thematically, there was something missing. Then I went to the Bear River Writers’ Conference, and fabulous poet and author Laura Kasischke gave this prompt: write for five minutes about a lie you told or were told; write for five minutes about a weather event; and then write for five minutes weaving those two together. That’s where the first story, “Heart,” came from, and I knew that voice—Marie—had more to say. I began to imagine her as the author of these other stories I had written. The book came together when it became an exploration of writing about the self—the self as in the body and the self as in character-as-writer; me but not me, the line between truth and fiction.

And that gets us to your writing about self as body, as well as the self separated from or even in opposition to the body. Through illness, substance use, sexuality—even just social awkwardness—the bodies of the characters refuse to let the mind alone define the self. Was this part of your project or did it emerge as you wrote?

I think that’s exactly right, and I’m glad you saw that in your reading. I saw a parallel in the way the body attacks itself in an autoimmune disease to the way guilt attacks the mind. The bodies of many of these characters define, in some ways, the boundaries of their lives; and have a bigger influence on the mind than the mind has on the body.

And as I keep reading the stories, the bodies of many of the characters almost seem to extend down to a child or back to a parent, often against their will. Do you see a continuity of self that refuses to be bounded by just the individual lifespan of a single character?

That’s so interesting to think about. Yes, I was thinking about the ways autoimmunity often runs in families, and also the way addiction permeates generations—and affects the minds and bodies of those who know and love an addict, and causes stress and guilt, both of which have physical effects. Also, the feeling of outsiderness that comes with illness and addiction. That’s why Marie feels so drawn to Patrick. There are no trips to AA or Al-Anon in this book, though maybe there should be.

I’m so interested in this, and in how these characters try to solve problems they have with one person by influencing a different person. In part, Marie tries to solve Patrick because she lost the chance to solve her father. In “The Beast,” Beverly directly confronts Hadrian to address the evasion and deception of her husband Robert. And then in “Future Breakfasts,” Frances seems to present herself to her ex-boyfriend Byron so that Byron can resolve the trauma that Frances’s brother Duck caused him. Do you see this as an extension of illness? Of trying to control one element of life because another is beyond control?

I’m so interested in this reading, which I love so much. You’re completely right that these characters displace what they can’t control by trying to solve something else. A past relationship, a new relationship, an addiction. I think those might be pretty classic signs of codependency in the ways these characters distort reality, and codependency is what we think of as the condition of those who have relationships to addicts. But the idea of it as an extension of autoimmunity is fascinating to me, because autoimmune diseases, especially in the beginning before diagnosis, are incredibly manipulative. And invisible. It can be hard for a sick person to feel believed. And it makes sense you might then develop behaviors that are codependent in their own way. Controlling other aspects of your life, ignoring what’s wrong. In “Aerosol,” the protagonist almost dies because she refuses to admit her wound is serious enough to need treatment.

Can you also talk about Newark? It seems to define a lot of the book’s focus on places and times that seem removed from the center of things. The vacation town of Opal in “We Are Holding Our Own” is described as a place “of passing through.” Marie finally writes her book only after she moves away from Newark to Brooklyn—a place that people think of as a center of culture (or at least of self-importance). And in what may well be my favorite line of the book, Marie describes a passage of her life this way: “The years since then seem to have come and gone without taking off their coats.” Do you see Newark capturing this situation of neither-here-nor-there?

This is such a good question. I think most simply I set the frame of the book in Newark because it’s a city I love, and the city I was living in when I started this book, started Marie’s story. But Marie finds herself there because she moved there with her boyfriend, Ralph, but then they break up and he moves away, and she makes the decision to start over by staying there. She doesn’t want it to be a place of passing through, but it inevitably becomes one because she’s not at a stage in her life—her life is so insecure, she has no forward momentum—to really settle down everywhere. And she lives in a big city, with so much history, but her world is very small. She has a very tight knot of people—her neighbors, her landlord, and then Patrick—and I think in a lot of ways keeping her life so small is a way to feel physically like an outsider, something she seeks out because she’s likes to feel like an outsider emotionally; it’s a feeling she enjoys, and it’s not one of her better qualities. So she works in the city but goes home to Newark; her doctor is in the suburbs but she goes home to Newark. She likes this separation. Eventually she has to leave Newark in search of health insurance.

I think it would be bizarre to pretend in this interview that all we’re talking about is writing in the abstract, as though all these things—illness, lack of control, living in limbo—aren’t writ large in society and politics right now. COVID, government dysfunction, and the ongoing reckoning with anti-Black violence are forcing us to confront exactly these things very personally. So I think it’s important to ask: how are you doing these days? How are you feeling about the conversation that the book might have with these crises we’re in?

I’m so glad you asked this, because all writing is political. The personal is political. Illness is political. In a more abstract sense, I hope the book might catch the interest of readers looking to find meaning in instability. The book is coming out in a moment of great uncertainty, but in a way, this uncertainty has been here all along—we just hid it from ourselves. And now we’re in a place where we can no longer. On a personal level, that’s Marie’s story, ignoring problems until they come to settle accounts. Whether or not she succeeds in the reckoning . . . but she tries, she fights. She has work to do.