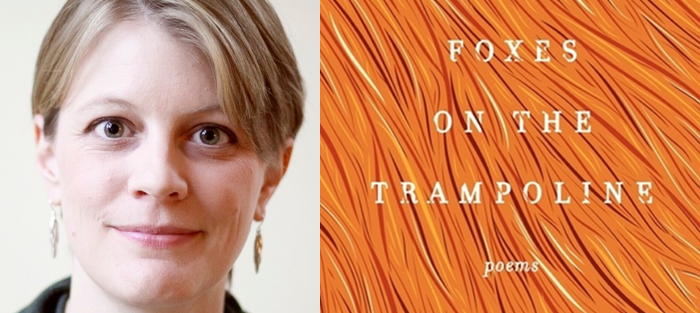

What follows is a conversation conducted via email between two poets, Lucy Biederman and Charlotte Boulay. In April 2014, Charlotte’s first book, Foxes on the Trampoline, was published by Ecco Press. Lucy and Charlotte are old friends from graduate school who haven’t seen each other in a long time, and they decided to have a chat about the book, and about poetry in general. Other things creep in too.

This interview took place between May of 2014 and January of 2015. We feature this conversation in celebration of National Poetry Month. Enjoy.

Interview:

May 10, 2014

Charlotte, your book is GREAT. I love it. There are so many poems in it that I am crazy about, and the way it’s put together is beautiful. I am so excited to discuss it—I think it’s stunning. Every time I read it I have a lump in my throat. Those final lines of “American Songbook”…

Congratulations—so, so, so beautiful. I feel so happy, because sometimes I get so upset that so much poetry is so shitty…and then finally I encounter something like this and I remember why I love it.

Love, Lucy

__

May 12, 2014

Hi Lucy, thanks so much! I’m excited to email with you about it, and would love the conversation to include your own work as well.

Is your semester over? What are you doing this summer?

Love, charlotte

__

May 12, 2014

Yep! My semester is over! I’m teaching an 8-9 am comp class, studying for my last two comprehensive exams, and writing an article about Henry James that will be part of my dissertation—I’m going to present on it at MLA in Vancouver. I’m on a panel with some seriously academic-looking people, it’s freaky.

To the interview: there’s one question I’m dying to ask you—or, rather, an issue I’m so eager to bring up after reading and loving your book. Through Foxes, I thought of something that we talked a lot about at Michigan, and that seems so central to the success of a poem, yet so ethereal, or inscrutable, or something: tone. Here are three passages I keep going back to (even in my dreams!) and I wondered if you could talk a little about their tones—the choices you made in terms of punctuation, line breaks, sentence variation, spacing, to create those tones? Or … did you make those choices? How would you describe their tones? Is tone describable?

Our lungs are just one balloon after

and after another. You can keep on going.

You can go on out.

—“Black Excursion #13”

What I want is folded up somewhere,

or buried, or slipped under the sea. I have everything

else, everything everything.

—“Foxes on the Trampoline”

This world

is trouble through which I’m treading my way.

I’ve been working on the rail

road, all the livelong day.

—“American Songbook”

Love, Lucy

__

May 13, 2014

Lucy,

You’re so right: tone can be one of those inscrutable aspects of a poem that determine its success or lack thereof, although I think there may also be others as well. I remember reading an interview with Geoff Dyer where he said that if he’s figured out the tone of a piece he’s working on, he’s fine. If he’s struggling to define the tone, he’s completely miserable, and I feel that’s true for me. Although that doesn’t mean it’s the first thing I try to figure out. I think I’m surprised pretty frequently to find that what I thought was a somber poem ends up needing to switch to lightness, or less often vice versa. A few lines I love come at the end of Nancy Willard’s poem “Hindsight” (she retitled it later as “Bridget’s Confession,” but it appeared first under this much better title…):

Oh why did I let that boy go?

God himself loved the sight of us.

I would be the blue light in his eye,

the left one, the farseeing one,

the one he’s rubbing now, maybe.

It’s that “maybe” that draws me in, that uncertainty, or doubt. (A somewhat universal appeal, if Carly Rae Jepsen’s success means anything.) So things that help formally create the tone in the examples above are the enjambment, and the repetition, and rhyme.

In “Black Excursion,” even though the statements are imperative, the lines before them try to soften the command a little, with “just” and “after / and after”. It’s an overdramatic poem, so I was probably shrinking back from that a little. In the title poem, “everything everything” without punctuation feels like a lot, like already too much, but still not enough, and repeating that word speeds up the line instead of lingering on the sadness of it. Everything is a fast word. At least, that’s what I hope it feels like. And in “American Songbook,” letting the sing-song of “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad” come in at the end I hope helps keep the poem from being as overdramatic as it could be otherwise. It’s partly meant to recall the first poem in the book, which is also about work, and about the difference between physical labor and other kinds of work.

This impulse—to pull back from what could be the most serious tone in which I would let myself write—is one I have to watch. Sometimes there’s every reason to be a little self-deprecating, or humorous about things, and sometimes that’s an evasion. And I’m still not describing that tone accurately, I think. Nancy Willard’s “maybe” isn’t self-deprecating, exactly, but without it that line would feel forced, and the whole poem off somehow. It’s as if she’s really telling the truth, because she can’t pretend that she’s fully describing the memory accurately, or the outcome of her regret, or any possible intervention, supernatural or otherwise, and denying all those things allows the possibility of all of them to co-exist, which is much more complex than a poem that says: I’m thinking about a man, so he must now be thinking about me.

This is way more fun than writing grant proposals, to which I must now buckle down…

MLA in Vancouver! That sounds dreamy. I’ve always wanted to go to Vancouver. Can I read the Henry James article when it’s finished?

Love, charlotte

__

May 13, 2014

Charlotte—

I love that you brought up Geoff Dyer, because I have been thinking about how your poems are described as having to do with travel on the back cover of the book, and I think of Geoff Dyer as one of those writers, too, who is considered a travel writer, but whom I don’t categorize that way, because the real meat of the travel in his books isn’t external. In Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi, or even in the D.H. Lawrence book, Out of Sheer Rage, he’s talking about how far you can go away from yourself, inside yourself. I see that kind of “travel” so much in your poems.

In terms of tone, what’s so beautiful for me about those poems of yours that I brought up previously, and why I keep returning to them, is that those moments are so tonally surprising—SHOCKING, even. Your tones change so much, not poem to poem, but WITHIN poems, like light moving quickly across a room that changes the entire feeling of being in the room, or clouds moving really fast across the sky and changing the whole landscape. So I see what you mean when you talk about ending a somber poem with lightness, or a shrinking back. It’s like that shock of SILENCE in the phrase “all the livelong day” after the noise and song of the preceding lines of “American Songbook.” But I know exactly what you mean when you say that’s not quite right, about the Nancy Willard poem’s tone, because there IS something about describing tone with all these prosaic words that seems inadequate. I love that, because it’s such EVIDENCE of poems saying what’s unsayable by any other means.

I’m so interested in your comments about overdramatic poems! I don’t think I would think of “American Songbook” or “Black Excursion” as dramatic. Do you mean those sweeping high lyric statements like, in “American Songbook,” “we’re eating miles now, // driving into the night” or in “Black Excursion,” “By the end of our last days, the trees were / budding pink”? Who are some poets who you think of as dramatic, or overdramatic?

The next thing I want to ask about is eco-poetics. I am totally fascinated by your active and dire descriptions of nature, and I wonder if you consider yourself an eco-poet. Sometimes the sky is the most vividly alive thing in the poem: “What a wreck the sky is this morning, slashed / through the middle / and all bloody at the seams.” “Senza” ends with the couplet, “Want, world, want. The ice cream / is melting. It’s time to go home.” I think this speaks to the profound depth and breadth of WANT that drips onto every page of the book. We have “everything everything,” and still… It’s hard to read ice cream in a poem without thinking of Stevens; but I wonder if the “concupiscence” that consoled him is available to us, anymore: our world is melting. What responsibility, if any, do you think poets have to speak to our changing natural landscape?

Oh! Henry James—I made it sound more sexy than it is, but I would love for you to read it when it’s done. It’s actually about OTHER people writing about James, how there was this whole huge thing about David Lodge and Colm Toibin BOTH writing novels about James in the same year (2004), but did you know that Joyce Carol Oates and Cynthia Ozick both wrote novellas about James four years later? Of course, this couldn’t be troped as a big, manly, anxiety of authorship situation, so it didn’t get the same sort of press, even in scholarly journals. What’s really interesting is that Toibin and Lodge wrote super-traditional novels, and Oates’s and Ozick’s are quite postmodern, so you come up with a whole different set of issues—and a whole different view of JAMES!—if you kind of imagine a world where their novellas got the press I think they probably deserved.

Love, Lucy

___

May 19, 2014

Lucy,

On being dramatic: I do mean those sweeping high lyric statements. I think of the confessional poets as the most overdramatic, but their drama is often deserved. I’m interested in the truth of the thing the poem is trying to say being overtaken or inflated by the world of the poem itself, or by language. That seems both seductive and dangerous. In some of Sylvia Plath’s work, for example, I’m completely drawn in, but then when I back away from it I just really want to rub her back soothingly, or encourage her to take a walk and calm down a little. Her frenzy and intensity, which I’m labeling “drama” here, makes me nervous, even as I admire it hugely, and feel that I’m incapable of attempting any similar level of intensity, a fact for which I’m mostly very grateful. But then not practicing that intensity may mean it’s more difficult to access when you need it? And I’m interested in the juxtaposition of high and low—maybe that’s a clearer way to express some of the tone discussion. So “Senza” is struggling with the big idea of Desire, but also the ice cream needs to get put in the freezer before it’s just a sticky mess.

I don’t think poets have a responsibility to do anything, which is the great thing about being a poet. And the competing but equally true fact is that to write good poems poets have a great number of responsibilities. If you’re going to write about nature right now, or to pay attention to the natural world, there’s very little consolation in it. I didn’t think of Stevens with that ice cream, but I love that connection! I don’t know that I think of myself as an eco-poet. I’d like to? Mainly right now because I’m working full-time at a non-poetry job and I’m trying to fit poems in around the edges, I don’t feel like I have a great big-picture view of Poetry, or theories/school/contexts/labels like eco-poetry. If I write a new poem, it’s been a great week. Because of my day job my writing time is almost exclusively in the early mornings or occasional evenings, which may explain the large role the sky plays in this book—there’s often something dramatic happening in it at the ends of the day. I’ll have to try to write a high noon poem, when everything is flat and still, for a change. I’ve been re-reading Frank O’Hara’s Lunch Poems recently, and remembering your fierce love for that book…I’d also love to hear about your sky-poem connections—the cover of your chapbook, The Other World, is sky-filled, and I recall expanses in the landscapes in those poems (although I don’t have it in front of me in my cubicle, as I steal time to write this).

I don’t think poets have a responsibility to do anything, which is the great thing about being a poet. And the competing but equally true fact is that to write good poems poets have a great number of responsibilities. If you’re going to write about nature right now, or to pay attention to the natural world, there’s very little consolation in it. I didn’t think of Stevens with that ice cream, but I love that connection! I don’t know that I think of myself as an eco-poet. I’d like to? Mainly right now because I’m working full-time at a non-poetry job and I’m trying to fit poems in around the edges, I don’t feel like I have a great big-picture view of Poetry, or theories/school/contexts/labels like eco-poetry. If I write a new poem, it’s been a great week. Because of my day job my writing time is almost exclusively in the early mornings or occasional evenings, which may explain the large role the sky plays in this book—there’s often something dramatic happening in it at the ends of the day. I’ll have to try to write a high noon poem, when everything is flat and still, for a change. I’ve been re-reading Frank O’Hara’s Lunch Poems recently, and remembering your fierce love for that book…I’d also love to hear about your sky-poem connections—the cover of your chapbook, The Other World, is sky-filled, and I recall expanses in the landscapes in those poems (although I don’t have it in front of me in my cubicle, as I steal time to write this).

Love, charlotte

__

May 21, 2014

I’m so interested in what you say about poets having no responsibility but to the poem—and that with that comes many responsibilities. Do you mean responsibilities of action, craft, pedagogy?

Re: eco-poetry, I don’t quite think of “eco-poetry” as a school or label, like alt-lit or flarf or confessional or nature poetry; I think the “eco” reaches out to touch something outside of Literature. I say that because I truly believe W.S. Merwin when he says it means something different to be a poet now than it ever did before, now that we know how the world is going to end (he means global warming). Obviously that’s just one opinion, but it is an opinion I share.

We talked about this a lot in my MFA program at George Mason University, especially my professor Jennifer Atkinson, who is a High Eco-Poet of the First Order (omg that sounds like a cult, especially as a hyper link). Maybe it’s because of that background that when I read “Want, world, want. The ice cream / is melting. It’s time to go home,” I think the “ice [caps]” are melting. But I don’t think that’s a stretch. All the world’s wanting HAS led the ice caps to melt. If I were writing a review of your book, I would say something about that. Do you think this is a misreading? I love what you say, “but also the ice cream needs to get put in the freezer before it’s just a sticky mess.” I think one of the things that is so interesting about your book is the way the speaker continually checks her more “dramatic” impulses, turning around and walking away after saying something heartbreakingly beautiful. The poem never ends with the clashing symbols of sunset or sunrise; it’s always the quotidian melting ice cream. There’s a rootedness of the boredom of daily stuff that works so beautifully against (as Frank O’Hara would put it) “the big things of night.”

I just realized I have to go because my ice cream is LITERALLY melting—I just came back from the grocery store and the bags are sitting around on the floor. But before I go, I have another question. One of the two poems titled “Field,” in the middle of the book, begins with the lines, “In these months you’ve become / invisible as a page turner.” I love how that can be read as directed to someone whose invisibility the speaker is comparing to that of a page turner—or to the reader: your page turning has become invisible, you are a part of this now. Who is your ideal reader, and what are their habits? Dictionary-grabbing? Reading out loud? Would you want them to have seen, say, the Copley painting in “Watson and the Shark”? How many times would they read a poem? What would they come to this book—or any book—wanting (if anything)?

Love, Lucy

__

June 19, 2014

Lucy!

I am so sorry I abandoned our conversation. I have many excuses, some of them better than others. Actually, what happened was the science museum I work for opened a new wing on June 14, and everyone got hysterical about it, and I got swamped, or swamped myself, not sure, and I’ve worked more in the past 30 days than I ever have, and I always wanted to find more time to think carefully about the questions you’re asking, but I never seemed to have it. I’m sorry. Here’s me doing my best to get back in:

As I go about this busy life of not writing poetry, when I grab the hours I can to actually write it, I can’t be worried about my own responsibilities to Poetry—that’s too big a burden to carry to the desk. So the responsibilities, can, I think, only be to the words on the page—to the reader who is not myself but not not myself. I have a responsibility to that paradox to not fudge it, or be easy with it, and to make it as good as I can. I love what you say about Merwin and the crisis of the planet, of course—that’s the sword of Damocles hanging over our heads forever, and I love that you’re reading the poem in that doomed light. But even as the world is dissolving around us, we still have to make it through the week, right? So I think the retreat in some of the poems is speaking to that. Jorie Graham’s last book Place dealt with the ruination of the environment quite a bit, as do some of her earlier works, but she does it at length, over and over, and fairly straight (even lecturing, at times), and I’m not able to immerse myself in it the way she does, though I admire that concentration, and stamina, though there’ s very little humor in it, isn’t there? I don’t have time. And yet, not having time is what will doom us further.

I think my ideal reader would come to poetry—any poetry—with the desire for a break for everything else. Poetry is like nothing else, isn’t that why we love it? It forces me, and I hope mine forces others, to SLOW THE FUCK DOWN. I read everything else so quickly, and I’m so impatient with the world so much of the time, but I can’t be with poetry, because it won’t tolerate that mode. To me, it’s the necessary corrective to everything that overstimulates me otherwise, even though the best poems deliver their own overstimulation—but it feels different. A slow buzzing under the skin, rather than a crushing headache, or something. I don’t care if the reader has seen the painting—that’s my job, to make them want to, but I care that they’re willing to put down their phone and sit with a poem for a while, even if just a few solid, quiet minutes. Somehow that seems a lot to ask, as my own delay in replying proves that I have trouble asking it of myself these days…

Love, charlotte

__

July 11, 2014

Hi Charlotte!

“But even as the world is dissolving around us, we still have to make it through the week, right? So I think the retreat in some of the poems is speaking to that.” <–YES. I know exactly what you mean. I love the way in your book, and in your poems again and again, if feels like you approach, attack, and then recede from a sense of anxiety/terror, and then back into the week. And I could not agree with you more, it’s so unpleasant to be lectured to, in poems or in anything. I heard that people don’t care about climate change not because they don’t think it’s a big deal, but because it’s just such a huge deal, they feel paralyzed so they just stop thinking about it. Which I think speaks strongly to how off the TONE is in climate change discussions, speeches, even poems.

Would you or have you ever written a political poem? Do you think a poem can be lyric AND political at once? In “Planting Daffodils,” you write,

This fall, digging little graves, I can hear

winter approaching like the war

that already rages, not with drumbeats and shots

but silence, a great lack

of lucidity and grace.

I love how—by making it nearly a parenthetical—you present “the war” in all its presence and reality and distance.

There aren’t a lot of political poems around these days—and obviously the Inaugural poem always gets slammed by academic poets. The other day I was reading this long, long, long poem about Lenin by Mayakovsky. It was like “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomed,” but about Lenin not Lincoln. My brilliant friend Jennifer Morrison says people are reverent because they’re lazy. They don’t want to go seek out and study and pore through the information themselves, to argue or see if they agree, so they just choose reverence, and that way they don’t have to be good or great or anything other than neutral; they can revere instead. The idea of great reverence—particularly political reverence, coming down hard to align with someone else on one side or the other—seems antithetical to the bravery of great poetry!

I love talking about these issues of craft and writing, especially in particular relation to poetry. You know what’s strange about being back in school? I thought I would be around a lot of other writers, but getting my Ph.D. in English Lit, even though my specialty is creative writing, it’s not really a creative thing, and most people aren’t creative writers, so I don’t really talk about writing with anyone! It’s awesome to talk about literature, and to consider literature in an almost historical way, to think of books as doing “cultural work” (as Jane Tomkins says), or seeing them as pins on a huge map of Literature. I’ve never thought of books that way before—my brother used to make fun of me because I’d read a book really quickly without even looking at the title & have no idea what I had just read, and be like, “NEXT!” It expands my whole way of thinking to learn to read this new way, but it has nothing to do with writing or thinking as a poet.

Congratulations on opening the new wing, and especially on being done with opening the new wing. I hope you get to not work so hard now! Hope you’re having a beautiful summer so far.

Love, Lucy

__

July 15, 2014

Hi Lucy,

So much to say about political poems. First, I think that I talked a lot about wanting to write political poems in my essay applying to Michigan as a graduate student in 2002. I was working for a labor union at the time, and I had just returned from a year teaching in India, and I was going to change the world. And then I wrote a lot of those poems in the program—poems about poverty, and economic injustice—and very few of them ever got published anywhere, and they were always the most problematic to discuss in workshop, and it’s not a mode I stuck with, ultimately, because of TONE, exactly as you said. And most of that difficulty was that these aren’t issues that actually affect me directly—I was an onlooker, from my place of privilege, and I didn’t really have anything substantial to say about them besides, “Oh, isn’t this awful.” And in general, it’s never worked for me, to try to begin writing a poem with a moral outlook in mind, or a poem “about” a particular problem or viewpoint—it always feels forced. I wonder if it feels that way to you?

Still, those issues were things I wanted to talk about, things that mattered to me then and still matter to me now, and I haven’t found a way to do that at all. I don’t think it’s that the political more broadly is incompatible with the lyric, but that it tends too firmly toward a Truth, and doesn’t allow enough room for doubt to creep in around it, and so the tone gets stuck. Louise Gluck says, “Honest speech is a relief and not a discovery,” and I’m not even sure if I agree with that or not (sidebar: I’m re-reading Proofs and Theories right now, and there are so many pronouncements like that—some I love and some I hate).

“Planting Daffodils” is one of the oldest poems in the book, and I’m so sick of it by now, but I hope that it is succeeding at being lyric and political at once, which I certainly believe poems can do. (Louise Gluck also talks about how it is completely natural to hate your work once it has been published, and that this is a sign of progress, but it’s hard to say because you’re supposed to feel so grateful and proud that you’ve been published. Which, yes, but I am a really slow writer, and also the publishing process takes awhile, so I’ve moved on but the poems have stood still. It’s okay.) I feel surrounded by political poetry lately, but maybe we’re thinking of it in different ways.

Lorna Goodison, for example, who took pity on the relentless and naive sincerity in my application essay and let me into the program at Michigan, has a body of work of lyric political poems, as she writes the life of her family and community in Jamaica into being—I think that’s a political act. Obviously Patricia Lockwood is a fiercely political poet. Brian Turner’s lyrics about his service in Iraq. Michael Ondaatje’s book The Cinnamon Peeler. The inaugural poem—what a terrible assignment. I guess people do as well as they can, but I can’t say I’ve liked or felt moved by any of them, but maybe I’m too close and judging them even as the words come out of their mouths because it’s the only time poetry really has a national stage in this country. It’s the “coming down hard to align with something” that’s the trouble with political poetry, as you say, and a trick to pull off well that I don’t know how to do. But I think about it a lot, especially every six months when another article comes out that claims that poetry doesn’t DO anything, which is a conversation that’s so old and tired, and I’d like to say it misses the entire point of poetry, but really it only misses half the point, maybe. I mean, it would be nice if poetry had more power, but to do that I think it might have to give up what makes it good.

Lorna Goodison, for example, who took pity on the relentless and naive sincerity in my application essay and let me into the program at Michigan, has a body of work of lyric political poems, as she writes the life of her family and community in Jamaica into being—I think that’s a political act. Obviously Patricia Lockwood is a fiercely political poet. Brian Turner’s lyrics about his service in Iraq. Michael Ondaatje’s book The Cinnamon Peeler. The inaugural poem—what a terrible assignment. I guess people do as well as they can, but I can’t say I’ve liked or felt moved by any of them, but maybe I’m too close and judging them even as the words come out of their mouths because it’s the only time poetry really has a national stage in this country. It’s the “coming down hard to align with something” that’s the trouble with political poetry, as you say, and a trick to pull off well that I don’t know how to do. But I think about it a lot, especially every six months when another article comes out that claims that poetry doesn’t DO anything, which is a conversation that’s so old and tired, and I’d like to say it misses the entire point of poetry, but really it only misses half the point, maybe. I mean, it would be nice if poetry had more power, but to do that I think it might have to give up what makes it good.

I would love to read that Mayakovsky poem. I agree with your brilliant friend Jennifer Morrison that reverence is lazy. Though I think of reverence in a religious or spiritual sense as actually being a lot of work, to prove to something how much you love it all the time, but that’s a different thing, and perhaps just as intellectually lazy. Whitman’s reverence for America still seems relevant because he includes ALL of it, right? The mess with the beauty, again, and it’s not jingoistic, but it is sincere. What do you think?

Do you think more people studying literature ought to need to learn to think like creative writers, or do you think that’s the province of the artist, not the scholar? I think you can be both (especially YOU), but why is there such a division of those modes of analysis?

Love,

Charlotte

__

August 26, 2014

Charlotte I’m really sorry I didn’t write all summer. I had a much busier summer than I thought I wd have & my inbox is a nightmare. I went to Yellowstone–w my boyfriend (…& his family…) & then to HAWAII w my mom & brothers! The semester is already underway & I’m furiously studying for my comp exams in lit theory, which terrifies me—they’re in abt two wks. FALL!!!! How are you? Love, Lucy

__

December 28, 2014

LUCY!

The year is dying! It’s almost dark here in Philadelphia (well, it’s cloudy, too) and it’s not even 4 o’clock. I want to end our interview (surely the longest interview ever, spatially, if not in words?) by talking about three of your poems, first “2008,” which I love because of the energy, of course; I’ve always always loved that about your poetry, but also because I don’t even know what Louise Gluck poem the epigraph is from, but in some ways in terms of energy she strikes me as being unlike you, although maybe I need to go back and re-read her (I do). I have actually been reading Averno lately, and it’s very deliberate (and mostly not funny), and the asides in “2008” of course are deliberate but don’t want to seem that way. I wonder if you can talk about the inspiration you took from “…unchanged, unchanged…” in reference to this poem? And then I wanted to talk about another poem on this page, “The Whole Time My Heart was Working,” which is a GREAT title, and it’s a great poem. Can you talk about both poems being about accidents, or the unexpected, and the role of the unexpected in your work? And where “2008” is in dialogue with Gluck, I read “The Whole Time” as being in dialogue with Dickinson, or rather I didn’t make that connection until I read the last line and the “He” and then it was Dickinson all over and that made so much SENSE.

Finally, I think of love as being enormously important to your poetry, in a way that I don’t think of it in anyone else’s, and part of that is your complete willingness to use the word “love” in both serious and tossed-off ways, until poems like “Airliner” make me wonder if it’s possible to use the word and not mean it, and if we really MEAN IT all the time, what is that about? What does that say about its power, and ours?

I hope your holiday was great and sparkly and fun, and I hope your exams went well. I have a wretched cold, so I’m going to go drink some bourbon. Happy New Year!

love, charlotte

__

December 29, 2014

Charlotte, I love the things you say about my poems so much. Like, I feel like you just gave me the best Christmas gift ever, of reading those poems and my poems so beautifully. Thank you. I don’t want to be too gushingly thankful because one of the things I despise most in interviews I read online (and I don’t know if this is normal or not, but most of the time I’m online there are lasers of hate shooting out of my eyes and my heart) is when the answer to every question begins, “Oh wow, GREAT question! No, YOU are great! YOU are SO, SMART! and *I* am so smart, and wonderful, to notice how smart and wonderful YOU are!” Like, why are so many interviews like that PUBLISHED? Fine, do that interview, but why PUBLISH it—who would want to read it? I mean, it seems like kind of a closed circuit, doesn’t it? [That aside, it gives me a beautiful feeling, the things you write about my poems—thank you so, so much]

When I got your email I had this essay by Karissa Morton open in another window, making me think hard about the hardness of Louise Gluck for the first time in a long time—I love her for being HARD in all meanings of the word, Plath-y multi-pronged hardness. I’m home at my mom’s house without my books, but that bit “unchanged, unchanged…” comes from a poem I used to think about ALL THE TIME, from her first book, where she gets married and drives away, and it’s like, I see my family, frozen in the doorway, “unchanged, unchanged.” Like across the divide of her marriage. AHHH!!!!! It’s suchhhh a good poem!!!! Meaningwise, I didn’t intend for the poem to reference hers, but formally…OMG I took so many inspirations from it, I could LIST them:

- It’s a sonnet.

- In the secret way that the poems in Louise Gluck’s first book are, where she just casts out the idea of meter at all and only uses rhyme (and I love how that makes the lines feel harder, or more “stacatto,” as I once heard Frank Bidart describe a line).

- The way she uses punctuation to signify/elide an EVENT.

Accidents/unexpected: that is such an interesting way to frame things. My very first memories of thinking are of being terrified of an accident or anything unexpected happening. Like, that fear is who I AM…And those types of events are what life is and how we perceive of it as moving forward. That’s it! So I wanted to, and want to, write a poem that is like THE thing itself, THE accident, the END, the FEAR. While meanwhile your heart is just beating, beating. And ABSOLUTELY this poem is so influenced by Dickinson, specifically here Dickinson VIA Heather Christle, whose poem “The Whole Thing Is The Hard Part” I copied the title from, and I think about all the time—it blooms and dies and blooms again all the time inside me.

Your love question is HARD. It makes me think about the Airplane poem and the other poem on that page, “That’s enough of that,” as a pair in a way I hadn’t before, because they are both kind of BAD-LOVE poems, like the bad love of a dream or wrong relationship or wrong day or hour in a relationship or sad marriage. I don’t know, people LIE so much. This is why I can’t be on Facebook, Charlotte. People lie so, so, so, SO much! I can’t stand it! Love isn’t this great thing! It’s good, bad, boring, sad, satisfying, scary, disappointing, lonely, exciting, weird, whatever, but it’s not just plain good-flavored good the way people present their love on Facebook. Because of social media, there must be more lies floating around about love than ever before. So for myself, even if it’s only for me, I have to shoot above that, toward a meaning I believe is really true, with words I CHOOSE, not that I have been GIVEN, like “amazing” or “incredible.”

OK, end rant. Oops! AHAH! I am having an excellent vacation here in Chicago, about to go back to Louisiana and have a little more vacation before heading to Vancouver for MLA. I even bought a suit to wear and everything, so it’s really serious.

Happy happy New Year—Love, Lucy

__

January 4, 2015

Wow, I hadn’t read or didn’t remember that poem “Bridal Piece,” but I just went and found it and it is so intense. That whole first book is, really. I haven’t read Faithful, Virtuous Night yet, have you? Maybe that’s how we should end this interview, by talking a little about what we’re both reading now? I always love when writers do that because my list can never be long enough. For poetry, the best book I read last year was Kiki Petrosino’s Hymn for the Black Terrific, and I’m also pretty completely obsessed by Lucie Brock-Broido’s Stay, Illusion. And otherwise today I finished reading Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel, which I loved loved loved, and I can’t believe I didn’t read it earlier, but I know why I didn’t: because so many of the reviews expressed such wonder that a “genre” book (all books are genre books) about a post-apocalyptic future could be so good, and that kind of thing drives me wild because I love fantasy and sci-fi and read it all the time and sure some of it is terrible, but a lot is amazing, and if I ever have to read one more book written by a guy from Brooklyn about whether his relationship/life/job is satisfying enough, I think I’ll just die. Give me the apocalypse any day of the week over that.

I love your description of “love” trying to shoot above everything, and the lying of social media. I know exactly what you mean, and I see it in myself online, and it feels a lot like we can either be isolated and honest, or together and lying like rugs, because honesty just doesn’t fit in so many of the forms that social media takes. Maybe none of them? Maybe because they don’t allow for all those different definitions of love in all its complexity and terrible beauty? Maybe only poetry can do that. I have a very vivid memory of a great poem of yours titled “Pulchritudinous” that I think about. I think about your describing what it was trying to do in workshop in the sort of the same way you’re talking about love here, but ten years ago. I don’t have many memories of that workshop anymore, but that is one.

GOOD LUCK at Vancouver with MLA! I have never been to Vancouver, but I love Seattle, and in a different life I would live there in a heartbeat. Lucy, this doesn’t have to be the end of our emailing! I hope it is not! I just want to get something off to FWR so I’ll draw a line under this part of it after you tell me what you’ve been reading lately, and then maybe we could continue? And be even more inappropriate because it won’t be public (although I’m not sure I care…)

I hope your 2015 is off to a great start,

love,

charlotte

__

January 18, 2015

I’m so excited that you read “Bridal Piece”! Total deep track. I REALLY want to read Station Eleven, especially after what you say about it. I’ve been thinking about genre, genres, genre boundaries, and genre STEREOTYPES so much lately while trying to start my dissertation! God there are a million ideas of books and stories and poems that I have, how weird and wild they could be, and they NEVER are! They just hew so closely to what’s already been done. Like, epiphany, epiphany, journey, Zzzzz. You love fantasy and sci-fi?! WOW! I had no idea! I was just thinking about how I have this huge desire to just read STORIES all the time. Like, the things I read for Ph.D. school don’t even begin to satisfy it. I need to get all these books from the library and just read them all the time. Stories, stories! I want *that* AND I want REAL experimentation, actual, true, experiments, something that dares to not even try to be a story at all. The two best ungenreable books I read this year were One-Way Street, by Walter Benjamin and Borderlands/La Frontera, by Gloria Anzaldua.

This year I got into this phase of reading a lot of novels about Americans in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan–and the best BY FAR (a MILLION times better than Phil Klay’s Redeployment, which felt really *mannered* to me) was Billy Lynn’s Long Half-Time Walk, by Ben Fountain. I think about it every single day. Billy Lynn is this 19-year-old Bravo soldier who just WENT to Iraq. He didn’t know what he was doing. And you see what a life-making decision that is, but how it was basically a set-up from the beginning—what else would a person with his same life have done? But it isn’t pedantic at all—there’s absolutely nothing pedantic about it, because Ben Fountain makes Billy Lynn such a REAL person—so so so real it breaks my heart. He’s so un-wise—he’s just this GUY. There’s this one part where he vaguely gets the sense of how unequipped he is that I think about intensely, constantly, especially when I’m teaching, that’s like, if there was anything to learn at public school, he didn’t learn it, “and only lately has he started to feel the loss, the huge criminal act of his state-sanctioned ignorance as he struggles to understand the wider world. How it works, who gains, who loses, who decides. It is not a casual thing, this knowledge. In a way it might be everything.”

MLA was EXHAUSTING! I’m glad I went because now I never have to go for the first time again! I felt like I was saying the wrong thing, wearing the wrong thing, going to the wrong panels…Yikes. I would love to share my James paper with you. I’m attaching it to this email. Thank you for asking to read it. There are actually two versions, the short, conference paper, version, and the longer, academic article version, both of which I’m trying to edit and figure out how to get right. So if you have any suggestions, I would seriously love to hear them! But absolutely no pressure. Sometimes I ask to look at people’s things, then open the document and I’m like, shit, I’m not interested in this at all.

I don’t want to stop emailing, either. I’m sorry I’m not a more regular correspondent, but I love writing with you so much, and I love talking about books and words with you. It’s AWESOME to be in touch with you. Let’s keep doing it.

Love love love, Lucy