There’s a bohemian restaurant in upstate New York that’s known for its amazing food and its famous clientele. Years ago, when bands like REM or Metallica or Sonic Youth would put on a show in town, they’d walk from the performance arena across a bridge that spanned the Susquehanna River, just for the renowned fare and the quiet tables. An upright piano hugged the north wall, and on most nights, patrons of the restaurant could listen to a man play songs they knew from classic films and Broadway shows. These days, famous musicians are no longer coming to the arena to play, the restaurant has cut back on its hours during the week, and the piano player’s bench sits empty after the man’s death. The food is still amazing, though, and the backdrop was the perfect place to have dinner with Jaimee Wriston Colbert and to talk with her about her new collection of short stories, Wild Things.

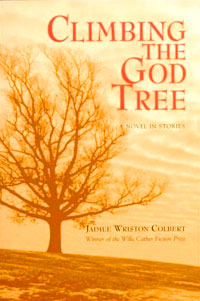

Before Wild Things, there was her second novel, Shark Girls (Livingston Press, 2009), which built a mythology around the survivor amputee of a shark attack, and before that was Wriston Colbert’s novel in stories, Climbing the God Tree (Helicon Nine, 1998), which garnered her the Willa Cather Fiction Prize, and her debut collection, Sex, Salvation, and the Automobile (winner of the Zephyr Publishing Prize, 1994). But in the last few years, her work has been championed by Kansas City’s BkMk Press, which published a stunning collection of stories, Dream Lives of Butterflies (2007), and also Wild Things, which has just been published.

The linked stories of Wild Thing center around the kidnapping of Loulie, a local girl from the economically depressed region, by an underemployed nature lover, Jones. But Jones believes he is rescuing the young woman from an unstable and abusive life, and he will keep her hidden away for as long as it takes. Down from the version of the Susquehanna River where the stories are set, just a few dozen yards away from its banks, Jaimee Wriston Colbert and I talked about the characters that populate her collection and the dark places they inhabit.

Interview:

Barrett Bowlin: When did you feel like you had the heart of Wild Things formed? Most of the stories in the collection have been published in literary journals, but when did it feel like you had a center to form the collection around?

Jaimee Wriston Colbert: I think it was with “Ghosts.” I had written a couple of the other stories before that, but that particular story focused on the abduction of Loulie by Jones, where he believes he is, in fact, rescuing her instead of abducting her. That started to make me realize I was in the bigger territory of where stories are connected, rather than in a collection where the stories don’t relate to each other. In fact, for a little while, I wondered if I needed to write it more as a novel. But the growing relationships between the stories made me start to see it as a “story community.” That was how I was originally thinking about “Ghosts,” because once it ended, with the girl still tied up in that trailer, I knew I had to revisit it. You don’t leave someone tied up and feel good and done.

Did you feel like you had to write other stories on top of “Ghosts” and “Migrants,” then, in order to build up that community, or did the stories you were writing around this time seem to connect to this event on their own?

Did you feel like you had to write other stories on top of “Ghosts” and “Migrants,” then, in order to build up that community, or did the stories you were writing around this time seem to connect to this event on their own?

I think I did end up feeling like I had to add to or develop the stories further. I felt like I needed some kind of follow-up to that, as a reference to the abduction, even obliquely. And so in a story like “Things Blow Up,” where one woman is taking another to the airport, there’s the reference to the story of the missing girl that brings those characters together. I found that I needed to build up other stories to carry that theme, to make it clear that the women are also part of this community. I ended up doing that to other stories, with “Dog Days,” for example. I had written the story originally to be fairly brutal, but I drew back on that impulse.

This goes back to the idea of truth being stranger than fiction. I had heard on the news that, in one of the Appalachian states, these dogs had been abandoned and wound up forming a pack and killing a couple that had been hiking. In the original story, I had the dogs killing a woman, and it was actually published that way. And people had commented about how brutal the story was. But eventually, I decided that the dogs in the story would serve better as a device to find the missing girl’s hoodie, which then appears several times in other stories and serves as another link between them.

You’ve mentioned in previous interviews that, to you, “place is character.” With several of the stories set in an unnamed location along the Susquehanna River, what would you say are the defining characteristics of this setting? What makes it the definitive spot to tell these characters’ stories?

I really focused on the river, the Susquehanna. It is, in fact, one of the most polluted rivers in the country. But like all rivers that flow through multiple states, it’s a lifeblood. It’s a vital thing to these areas that has meaning to people and to industry, as well. I visualized the area as an unnamed town in the rural Southern Tier [of New York], with that river as this entity that threads through and affects peoples’ lives in different ways. I have a character, for example, who imagines diving into the river and coming across all the solid waste of the local industries that has gone into that river and polluted it.

The stories in general are about environmental losses. The river serves as both a site of pollution as well as a means of freedom. It flows out of the area and it ultimately ends up in the Chesapeake region. It moves out in a way that the characters cannot since many are poor and stuck in this community.

And then there’s also the woods. They play a huge part in the stories. One of the things I was always fascinated with in Flannery O’Connor’s stories was how she uses the perimeter of woods. She uses the woods as an actual line of demarcation in her characters’ lives, and then the metaphorical line of woods and darkness, of trees and of mystery. I envisioned those lines of woods in Wild Things. I thought, Those who go into the woods do so at their peril. For example, Jones basically lives in a very private place in the woods. The little girl, as well, Fortune, who escapes for a while from taking care of her grandmother—she goes into a deer blind in the woods and imagines various things happening, and she sees Jones’ trailer and Loulie, the kidnapped girl, then does nothing about it. The woods is a place for characters to go into that is both refuge and danger. Bonnie Jo Campbell, one of my reviewers, called it “rural noir,” and I think she nailed it.

I think she did, too, but I wanted to bring up that sense of the gothic in your work, as well. You’ve got the presence of the economically dispossessed setting (particularly after IBM left the area), the characters’ warped mindsets of what “rescue” means, the grotesque acts of violence, and even some magical realism in some of the stories.

I think she did, too, but I wanted to bring up that sense of the gothic in your work, as well. You’ve got the presence of the economically dispossessed setting (particularly after IBM left the area), the characters’ warped mindsets of what “rescue” means, the grotesque acts of violence, and even some magical realism in some of the stories.

There is definitely that gothic sense to it. I do see it also, though, as stark realism. As you mentioned, IBM really did this. They pulled up their roots and left a lot of people in the area without jobs and without hope for jobs. A lot of the stories take place around 2008, when the housing bubble popped, when everything went to hell, so I see my characters struggling in the light of that economic depression, as well. Fortune, for example, is walking along the road to her grandmother’s, and she’s spying on everyone’s houses with the “For Sale” sign in the yards, and so many of the dogs have been abandoned and are running wild, and not a lot of the characters are working much anymore. So besides the gothic element and the noir element, I hope to make a statement on rural people’s lives and how they’ve suffered under the loss of manufacturing in rural America, especially in an area that was already hit very badly.

Similar to setting, let’s talk about the authors and works that have influenced the shape of Wild Things. For this particular collection, who would you say have been your primary literary influences (as opposed to previous collections)?

Absolutely Flannery O’Connor. There’s no doubt about it. She was considered “southern gothic,” and her territory was very rural. So I would say this is sort of “northeastern gothic,” but without the religion.

Booklist drew a comparison to Bonnie Jo Campbell, and I see it with her American Salvage collection, because her territory there is similar. It’s rural Michigan, but it has the same kind of post-manufacturing sense of defeat, where meth labs are a bigger business than just about anything. I think that’s just the way it is in rural America now. But I also think that not a lot of writers are writing about rural America—it’s more Boston or New York, more urban areas in their fiction—and I really wanted to bring to life what’s happening in rural areas. I think American Salvage definitely did that for Michigan.

I’ve been curious about this, too: what would you say has been the reason for the more violent stories in this collection? We have characters who die in house fires and meth lab explosions, and the stories center around this kidnapping, just to name a few of the more stark acts in the book.

I think it’s been our scarier times. It’s interesting—my publisher, Ben Furnish [of BkMk Press], and I were just talking about this. BkMk Press also published another collection of mine, Dream Lives of Butterflies, back in 2007, and those stories, I remember, were mostly from the ’90s, when there was that sense of false hope and when a lot of people were prospering. Though in my collection, none of my characters were prospering. I’m not interested in the struggles of prosperous folks. There wasn’t the sense of darkness at that time, however, so I think the violence in this book speaks to more uncertain times.

I think it’s been our scarier times. It’s interesting—my publisher, Ben Furnish [of BkMk Press], and I were just talking about this. BkMk Press also published another collection of mine, Dream Lives of Butterflies, back in 2007, and those stories, I remember, were mostly from the ’90s, when there was that sense of false hope and when a lot of people were prospering. Though in my collection, none of my characters were prospering. I’m not interested in the struggles of prosperous folks. There wasn’t the sense of darkness at that time, however, so I think the violence in this book speaks to more uncertain times.

And there’s also my own uncertainty. I see the collection as being very much about loss, both about personal loss and universal loss. I think a lot of the darkness comes from that. Take a story like “We Are All in Pieces”—that story is very much about species extinction and family losses, and then there’s the fact that the narrator has essentially lost her brother to heroin addiction. It looks like I’ve been wrapping up a decade with this collection, one where I’ve suffered personal losses, and so many others have suffered economically, on top of the environmental losses. So it’s dark, as a result, but not without humor.

And also, I am from Hawaii, as you know, and I recently found out that Hawaii is now known as the extinction capital of the world. There are more species disappearing every day there than any other place in the world, because it’s an isolated island group, where so many natives species once thrived. And of course people come and then all hell breaks loose, what with the diseases they bring in, the invasive species, et cetera.

Much like the violence, then, I’ve noticed you have the running theme of the ‘wild child’ throughout the collection, particularly in “Ghosts,” “Migrants,” “A Kind of Extinction,” and others. How do you think the “wild child” of a character like Loulie’s generation and the “wild child” of her mother’s generation differ?

Annalee’s (Loulie’s mother) generation’s “wild child” was about the ’60s, when being “wild” was cutting loose and taking recreational drugs for fun, with the mantra of “peace and love,” et cetera, versus today’s “wild child.” In a way, the wild children of today are characters like Fortune, in “A Kind of Extinction,” who’s the daughter of a Tea Partier mother, with both parents being more concerned with politics than her, and Fortune is just left to run around wild, spying on people. She’s the one who sees the abducted girl and does nothing about it while trying to think about how it can benefit her. So I would say that the “wild children” of today are much less idealistic. They’re much more about survivalism than idealism.

A point I wanted to come back to from before: as you mentioned, Wild Things is being published by BkMk Press, out of Kansas City. What first attracted you to their press? What made them a good spot to publish Wild Things and Dream Lives of Butterflies?

A point I wanted to come back to from before: as you mentioned, Wild Things is being published by BkMk Press, out of Kansas City. What first attracted you to their press? What made them a good spot to publish Wild Things and Dream Lives of Butterflies?

Having the opportunity to work with Ben Furnish is fabulous. He’s fabulous. I’ve found that they care so much about their books; you can’t just slip in there. Even though I had a book published by them before, they still couldn’t take Wild Things without it being vetted by three different readers and with extensive revisions each time.

Ben very much believed in the book. He would give me these revision notes each time, and it took a couple of years to get the acceptance from the press, but when I got the acceptance, it was so worth it. It wasn’t just his own personal taste, either; it went through a lot of work, and by the end of it, I felt like I had a pretty good book. [BkMk Press] puts so much care into their books, and they have such dedication and love for what they’re doing.

They have such a strong catalog, too. What drew you to them initially?

I remembering reading a couple of books published by BkMk. They’re one of these literary presses that you see around a lot. They sponsor some big competitions for poetry books and story collections, too. So I had seen a couple of their books and just thought they were a cut above. They were really, really good books. So when I wrote Dream Lives, I knew one of the people BkMk had published before, and I got in contact with her and asked her about Ben. It had to go through the same vetting as Wild Things, this long revision process. But in the end, I was just really happy with how it came out.

There are so many little presses now, and I think that the ones that have been around a long time shine by what they publish over the years. I mean, some of the newer presses are probably quite wonderful, too, but they have to put out a series of great books to be able to get that level of attention. Still, they’re doing a labor of love, because they believe in literature, and they’re willing to take risks that the trade presses generally can’t or won’t.

I have to ask, of course, but what are you working on now? In other interviews, you’ve hinted at the presence of magical realism in these manuscripts, so what would you say is responsible now for this stronger attraction toward magical realism?

I will say this much: I recently uncovered part of my ancestry I had no idea about, which is that my family in part comes from the Isle of Skye in Scotland, and that we are products of the Highland Clearances. My ancestors wound up being evicted from their home and coming over to Prince Edward Island, before coming to the United States. I became sort of fascinated with the story, and I decided I wanted to write a novel about it. But I’m not really good about writing memoir pieces or things from my own background, so naturally, I have to throw in some big, contemporary complications along with a little magical realism. So in the end, it’ll be the Clearances along with some craziness in the 21st century.

And then there’s Vanishing Acts, my new novel manuscript. It’s a strange little book involving a highly dysfunctional family in Hawaii and a father who believes that he can literally surf his way into invisibility, and that he can disappear himself. It uses a lot of Houdini’s illusions in it, as well; I got really interested in magic for a while. It has a lot of drug addiction, too, which seems to be a reoccurring theme of mine.

It is! But it’s part of such a solidly dark set of themes, something that I saw a lot of in Wild Things.

There are definitely those themes of parenthood and of ruined parenthoods and childhoods. In a lot of my stories, there’s that damaged parent-child relationship, say with a mother who’s deserted the family for whatever reason—depression, suicide, et cetera—or a father trying to pick up the pieces of a wrecked family. I think of Wild Things as a collection of stories that are bigger than just family stories, though, because they touch so heavily on environmental and economical losses. I mean, quite literally, the beaches are disappearing, the neighborhoods are crumbling. But it is also a series of personal relationships and losses, which are more at the parent-child, or siblings level. I’ve noticed that there are fewer love relationships than in previous books. There are fewer failed-love relationships, too.

You know, when I finished this book, I at first felt like it was limited to a very localized area. But after a while, it felt much bigger. It felt bigger than the setting, like it was more concerned about not just a particular environment but of multiple environments, and the environment as a whole, like it reflected so much more than my own personal concerns.