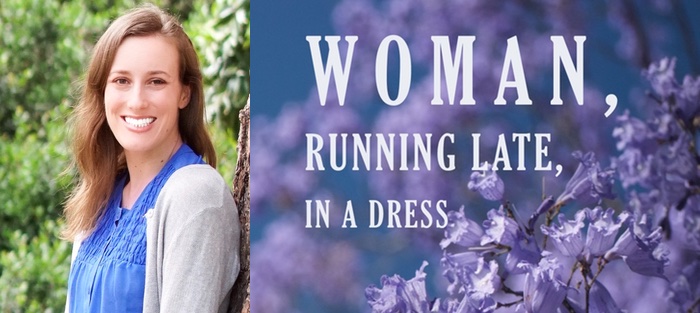

I first met Dallas Woodburn in 2013, when we both attended the Key West Literary Conference and were assigned housing together for the week. Our friendship was immediate and easy, and after our morning writing workshops we explored the quirky island together, laughing over the wild chickens and visiting Hemingway’s house. Though we don’t get to see each other much in person—she lives in California while I live in New Hampshire—we communicate frequently through emails, snail mail letters, and video calls. Our friendship is a real gift as we have evolved from our twenties into our thirties, navigating the ups and downs of the creative life.

I was thrilled when Dallas’s debut collection of short stories, Woman, Running Late, in a Dress was published by Yellow Flag Press in 2018. These thirteen linked stories examine the complexities and nuances of love, motherhood, grief, and identity, featuring an interrelated web of characters and storylines. An ordinary day for one character is a life-shattering day for another; a small, impulsive decision made by one character affects another’s life profoundly. A central theme is memory: the way it is nurtured, pushed away, and falsified, along with the tenuous gap between memory and real life. In addition to winning the Cypress & Pine Short Fiction Award, Woman, Running Late, in a Dress was a finalist for the Indie Star Book Award, the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction, the Augury Books Prose Award, and the Horatio Nelson Fiction Prize.

A 2014 Steinbeck Fellow in Creative Writing at San Jose State University, Dallas also won the international Glass Woman Prize and is a four-time nominee for the Pushcart Prize. Her short stories have appeared in ZYZZYVA, The Nashville Review, Superstition Review, Monkeybicycle, North Dakota Quarterly, and many other journals, as well as American Fiction 13: The Best Unpublished Short Stories by Emerging American Writers. Dallas and I corresponded for this interview over a series of emails.

Interview:

Carand Burnet: Much of Woman, Running Late, in a Dress follows the lives of characters in their twenties. How does highlighting this age range help shape your narratives?

Dallas Woodburn: It perhaps isn’t coincidental that I tend to most gravitate towards writing about characters who are teenagers (in my YA fiction) and characters in their twenties. I think both time periods are filled with such uncertainty, shifts in identity, massive growth, and trying to find one’s place in the world. These challenges are ripe for internal and external conflict—the lifeblood of stories! I am so interested in exploring the inner lives of my characters, and one’s twenties are such a liminal time period: not a child anymore, but not quite “grown up” yet either. Or, perhaps it is in your twenties that you realize that your concept of “adulthood” is in some ways an unreachable terrain—that you will never quite feel like you are in control or know what you are doing all the time. There is a personal component, too: I wrote all of these stories when I was in my twenties myself, and writing is a way for me to navigate my own life through a fictional lens.

So true! I remember when we first met in our twenties, and it seemed that during this time we were getting to know not only each other, but also deeply working out who we were ourselves. While it’s something that continues throughout life, it seems magnified during early adulthood.

So true! I remember when we first met in our twenties, and it seemed that during this time we were getting to know not only each other, but also deeply working out who we were ourselves. While it’s something that continues throughout life, it seems magnified during early adulthood.

How did characters in each story become revisited into later stories in the collection?

This was a really neat process for me as a writer. When I originally wrote first drafts of many of the stories, I didn’t realize they were linked. My subconscious was obviously at work, but my conscious brain was unaware. It was only when revising and viewing the collection as a cohesive whole that I began to realize that the same people were popping up again and again. Once I had that realization, it was fun to go back and revisit each character from different perspectives. I discovered many more connections and intersections during my many revised drafts—almost like fitting puzzle pieces together. I drew out a massive diagram with all of my characters and the ways in which their stories intersect, and that helped me keep the various narratives sorted out in my mind. I hope that the reader gets to know the characters as full-figured, flawed and complex people through the process of running into them again and again throughout the book. Also, as a writer and as a reader, I often wonder what happens to characters after the story ends. Revisiting characters in this way allowed me to “check up” on them later—and the reader gets a hint of where their lives go, too.

Memory plays an important role in your narratives. In your story “Three Sundays at the Grove” your character allowed the memory of her mother to grow into an antagonist, while in “Erik & Steffy” the main character uses his imagination to create memories of the deceased sister whom he had never met. These instances remind me of WG Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn, where Sebald describes the power of memory and how memories can lie dormant within a person for years, but when triggered, can awaken that person in a newfound way. Could you speak about memory and how it relates to your writing?

This is such an insightful question! Memory was certainly one of the major themes that emerged as I wrote this book. Building off your previous question, I am fascinated by the way that memory is intangible and impermanent; how different people might remember the same event in vastly different ways. I also love your point about how memories can lie dormant and then awaken in a newfound way. Much like reading the same book during different times of life can incite fresh realizations and connections—when I read The Great Gatsby as a thirty-one-year-old, the experience is incredibly different from the first time I read the book as a high school sophomore—I am fascinated by the way that our memories can evolve when we look back at various times of our lives. Or, in contrast, the way our memories might remain static even as we grow and change ourselves.

I am also curious about the way memory is both connected to us yet also unreachable. We can share memories and bring the past “back to life” again through the retelling, but we cannot return to the past, and the stories might become distorted over years of retelling. Some of my earliest “memories” are ones I’m not sure if I actually remember, or if I just imagine these memories so vividly from being told the stories again and again. I’ve also been thinking lately of the ways in which we are gatekeepers and preservers of memory for each other. I have so many memories of my four-month-old daughter already, but she will not remember any of them—she will only know this period of her life through the stories her father and I tell her. And yet, our perspective of these memories is incomplete because we of course cannot know what she is thinking and feeling right now.

I love the idea of being “gatekeepers and preservers of memory”! It’s amazing how writers can be so close yet still distant to this powerful, elusive part of being human. Especially now, memories seem easily manipulated because of experiences shared online. I have wondered whether the impulsive to digitally document and disseminate on social media—selfies, photographs, blogs—will possibly further conflate our personal memories. Maybe it is more important now than ever for writers to try and be the “gatekeepers and preservers of memory” in some way.

In areas of Woman, Running Late, in a Dress, parents either add tension or oppositely comfort the characters’ ideas of home. Being a new mother yourself, has your perspective of parenthood changed since this book’s publication?

Oh yes, my perspective has shifted immensely now that I am a parent myself! Parenthood was something I observed and tried to imagine, but there was so much I simply could not understand until going through it myself. Being a mom is the most difficult and also most rewarding role I have ever experienced. I have so much respect for parents everywhere, and I feel connected in a deeper way to every parent I see on the street or read about in a book. I expected becoming a mom to change my life, and it has in the most beautifully small and also monumental ways. I stay at home with my daughter, and so I spend all my time with her; it is remarkable how I can feel so connected to her, and also how she can seem so mysterious and unknowable at times. She grew inside me for nine months, and now she is in the world as her own distinct person. She grows and changes constantly, which both makes me proud and also breaks my heart a little. I hope that I was able to capture some essence of parenthood in the book even before becoming a parent myself. I need to go back and read it again now and see how my own perspective on the stories has changed.

How lovely! I can’t wait to read your future stories that will likely touch upon these ideas!

As a fiction writer, you inhabit the lives of your characters. Your collection overflows with such a range of emotion. There are moments of tragedy, humor, happiness, longing, grief, and bravery. What inspiration do you draw from to create such multidimensional characters?

Thank you! This brings me back to your question about writing characters in their twenties; to me at least, that decade was filled with such raw emotion. So much was new. Everything felt heightened. Every emotion was bursting with importance. So I drew upon all of the emotions I was feeing when I wrote these stories and imagined being these characters. I think emotions are the fabric that connects us all to each other. I can feel joy and empathize with everyone who has ever felt joy. When we fall in love, the experience is singular to us and yet also universal. Writing has always been a place where I feel free to delve into a full range of emotion—an outlet for exploring anger, grief, longing. Even the happiest of people have felt these painful emotions at times. I wanted my characters to seem like authentic, full-fledged people existing in complex wholeness.

How do your fiction and narratives typically develop?

I typically begin with character: getting to know a character and letting the narrative evolve by asking what my character would do in certain situations. What is my character struggling with? What does my character want to say? Sometimes, a story emerges instead plot-first, from something I read in the news (“Slowly, Slowly, Without Much Notice”) or something that comes to me in a dream (the riddle in “Woman, Running Late, in a Dress”). Occasionally, I will get a first line that pops into my head like a miraculous gift, as was the case with the first line of “Erik and Steffy.”

Could you speak about your revision process? How many rounds of edits do you typically find necessary to reach an equilibrium on the page?

I love how you phrase that—an “equilibrium on the page”—because a story never fully feels “completed” to me; it always seems like I can delve back in and rewrite more and more. Eventually, you have to let go and move on to other stories, other characters, other explorations. I typically go through at least four or five revisions for my stories. This book evolved over more than a decade of revising, and some of the stories are virtually unrecognizable from their first drafts. Others needed much less work. As a whole, it is a fulfilling project to look back on because this book grew with me as I gained confidence in my voice and grew into my own self as a writer.

How has writing helped you overcome adversity in your personal life?

I have heard it said many times that writers need a “thick skin” to be able to handle lots of rejection and criticism. I think this is true and has helped me handle rejection and criticism in other areas of my life as well. There is a sense of creating something wholly for yourself and to please yourself, and then unleashing that work out into the world, and when you let it go, it becomes something separate from you. The criticism is not a reflection of you, or even a reflection on the quality of the work; it is a chance for you to hone your own voice and perspective, and to grow. I try to view all disappointments in my life as opportunities for growth. Even the really painful experiences have been meaningful because they have taught me about myself. Writing has also given me an identity as someone who perseveres against all odds. The successes are that much sweeter and are savored that much more truly when they do arrive!

Enacting a creative life takes such courage and perseverance. I am so grateful to know you and be inspired by you and your writing. I can’t wait to read more of your wonderful work!

Thank you, my dear friend! Likewise!