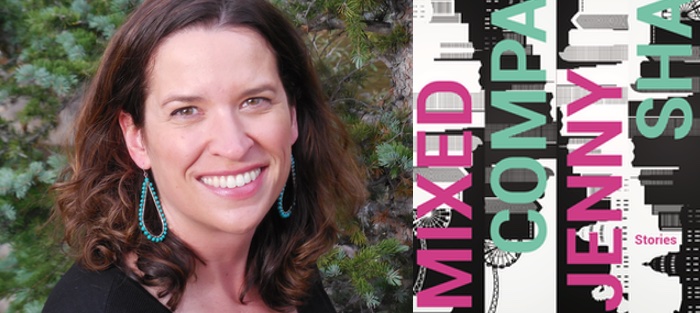

Jenny Shank’s insightful short story collection, Mixed Company, won the 2020 George Garrett Fiction Prize from the Texas Review Press. It will be published on November 15. In these twelve stories, Shank displays a perspective on life in Colorado that’s unlike that of any other contemporary writer. Mixed Company moves from stories of childhood busing for racial integration in Denver public schools to a tale of a one-woman sit-in at Senator Cory Gardner’s Fort Collins’ office. Many characters in these stories are out of their element—a Ph.D. English Literature student spends the summer tutoring college football linemen, who are more adept at sign language than she is; white parents take their adopted, teenage Black son to a Wu-Tang clan concert to bond; a girls’ basketball team at a majority Black Denver high school clashes with a white mountain team; and a young woman working in the Colorado Rockies Baseball Club’s Community Relations department organizes visits for sick children to watch their favorite baseball players and maybe, if they’re lucky, get a signed baseball or bat. Mixed Company even detours to France where a woman and her husband attempt to introduce their cute toddler to his mother, a shut-in with physical and mental health issues. Typical of Jenny Shank’s writing, these stories disarm you with humor and then break your heart.

Even though Jenny Shank and I both grew up in Colorado, we met in Vermont at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in 2006. A mutual friend had been telling us that we had to know each other. Jenny came up to my table to introduce herself, and we’ve been growing together as writers and instructors ever since. We both teach at Lighthouse Writers Workshop. Jenny also teaches at the Mile High MFA program at Regis University. We confess our publishing humiliations to one another and share our rejections. Sometimes when I’m teaching, I’ll describe a writing technique, and I won’t be sure who came up with a term first, me or Jenny. Along with our writing group friends, we created the Denver Literary Kidnapping & Drinking Club (where we attend book readings and then encourage the author to go out with us).

Jenny Shank’s novel The Ringer won the High Plains Book Award in 2012. Her writing has appeared in many outlets, including The Atlantic, The Washington Post, The Guardian, the Los Angeles Times and McSweeney’s. Shank is also a prolific book reviewer. Her opinion is the one I look to and trust. As a reviewer, instructor, and writer, Jenny’s honesty, humor, care, and determination continues to impress me. Like the best teachers, Jenny is generous with her publishing resources. And like most of us, Jenny’s characters try their best, but the situations don’t play out the way they expect. Even though I’m fortunate to know Jenny Shank well, so many of her answers to this interview made me appreciate her writing even more. And I hope you enjoy Mixed Company as much as I do.

Interview:

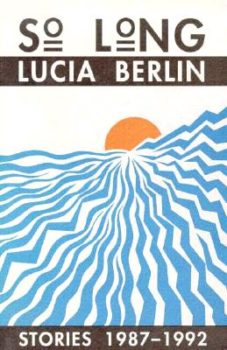

Paula Younger: You and I both shared (at different times) the amazing Lucia Berlin as a writing teacher, and you list her first in your acknowledgments. How much of a part did Lucia Berlin play in your career as a writer, and these stories in your collection? [Four of these stories were first written in her workshop.]

Jenny Shank: I feel like Lucia’s influence over me only grows the longer she’s been gone from my life. I wrote a whole essay about this that will be in the November/December issue of Poets & Writers, called “Lucia Berlin: My Mentor in Being an Outsider.” When I met Lucia, I’d just turned twenty-two. I appreciated her fiction from my vantage as a young person, but then after she died and Farrar, Straus, and Giroux released her selected stories, A Manual for Cleaning Women, to international acclaim, I read them all again, and I was moved and amazed to find all these layers, angles, and moments in the stories that I hadn’t perceived when I’d first read them. That’s what good literature does, I think—it offers something new to the reader every time you engage with it.

Jenny Shank: I feel like Lucia’s influence over me only grows the longer she’s been gone from my life. I wrote a whole essay about this that will be in the November/December issue of Poets & Writers, called “Lucia Berlin: My Mentor in Being an Outsider.” When I met Lucia, I’d just turned twenty-two. I appreciated her fiction from my vantage as a young person, but then after she died and Farrar, Straus, and Giroux released her selected stories, A Manual for Cleaning Women, to international acclaim, I read them all again, and I was moved and amazed to find all these layers, angles, and moments in the stories that I hadn’t perceived when I’d first read them. That’s what good literature does, I think—it offers something new to the reader every time you engage with it.

Lucia was my only fiction writing teacher and my thesis advisor in grad school, because everyone else on the faculty at the University of Colorado was on sick leave. She pointed me toward which books to read—I first discovered Haruki Murakami, Walter Mosely, and Marguerite Duras through her recommendations. She encouraged me, and pointed out any parts of my writing that struck a false note. But mostly, she taught me how to live as a writer in complete obscurity, and to keep writing anyway. She published only with small presses during her lifetime, and few people noticed her work. She taught me that writing short stories is a vocation, and the main reward you get from it is through communing with a small group of fellow writers and readers, and in joy of completing a story to your own satisfaction.

How did you come up with the title: Mixed Company?

It’s kind of a play on words—the old phrase “mixed company” meant a group of both men and women, and sometimes adults and children. It was often used to express a patriarchal sentiment, that you shouldn’t say certain words or discuss certain subjects “in mixed company.”

I think it’s a funny phrase, because the company I’ve kept has always been mixed—not just in terms of age and gender, but also in terms of ethnicity, disability, citizenship, and native language. I grew up going to schools that were extremely diverse because of the court-mandated crosstown busing. When I had my first experience of going to a school that was predominantly white and wealthy, in college at Notre Dame, it was disorienting. I remember thinking, “Where is everybody else?” Almost all the stories I write are generated from situations that occur when people of different backgrounds are forced to contend with each other.

Jess Row writes about this in his brilliant book of literary criticism, White Flights: Race, Fiction, and the American Imagination: “What would it mean to accept that America’s great and possibly catastrophic failure is its failure to imagine what it means to live together?” In Mixed Company, I try in my own way to imagine what it means for these characters to live together despite their differences.

Most of the stories in Mixed Company take place in Colorado (Denver and Boulder), but you do have a dash of Nebraska and France. The foundations of the locations seem to be in home and identity. How important is place in stories?

I think a sense of a particular place is essential to almost all writing. When I first taught creative writing to undergraduates at the University of Colorado, I noticed the first round of stories I received from my students felt, for lack of a better term, thin. For the second round, I required them to set their stories in some specific place, even if it was imaginary, and the stories I received the next time were a phenomenal improvement. It was like the writers had discovered gravity.

When I was starting out writing, there wasn’t much contemporary fiction set in Colorado, especially in the urban West. Most stories set in the West seemed to take place in rural areas, even though most of the population of the Western U.S. lives in cities and suburbs. And I’m not just surmising this—I was a book critic specializing in books set in the Western U.S. for many years. I combed through all the titles being published, and so many of them had horses on the book cover and taught me a lot about how to assist cows when it’s calving season.

When I was starting out writing, there wasn’t much contemporary fiction set in Colorado, especially in the urban West. Most stories set in the West seemed to take place in rural areas, even though most of the population of the Western U.S. lives in cities and suburbs. And I’m not just surmising this—I was a book critic specializing in books set in the Western U.S. for many years. I combed through all the titles being published, and so many of them had horses on the book cover and taught me a lot about how to assist cows when it’s calving season.

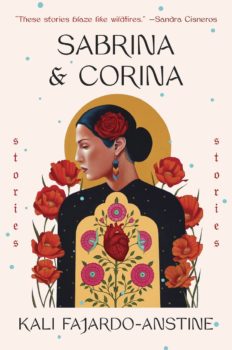

But in recent years, that’s changed. As publishers have focused on work by more diverse writers, there is more geographic diversity, and the urban West is appearing more often in wonderful fiction such as Kali Fajardo-Anstine’s Sabrina and Corina and Brian Washington’s Lot. So I hope my Denver stories will contribute to that trend.

I love how you use technology and modern life to time stamp and orient some your stories, but also to propel the action forward and provide tension. Cell phones have ruined some past movie and story plot points about characters unable to communicate in time. Now we are so linked it seems hard to separate. How you do feel technology impacted your stories? I’m thinking particularly of “La Sexycana” and “The Sit-In.”

I wrote these stories over many years, and technology evolved rapidly during that time. “La Sexycana” was set during the ascendancy of MySpace—I call it MyFace in the story. MySpace pages were wild—kind of like if a teen displayed her school locker decorations on the internet, complete with flashing lights. The story “Lightest Lights Against Darkest Darks” is set before everyone had cell phones, when if you wanted to call a friend, you often had to call their home phone and speak to their mom or dad. How scary that was when you were making your first, tentative attempt to reach out! And in “The Sit-In,” as you observe, technology offers a way for the busy mother of a child with disabilities to connect to likeminded others.

In my stories, I think about these varying technologies as vehicles for connection and disconnection among my characters. Some of the technologies make connection harder—like having to go through your friend’s mom before you can speak to your friend—and some make them easier, like publicly available webpages. But those avenues for easier connection often make for shallower relationships—the protagonist of “The Sit-In” makes online “friends,” but they end up leaving her alone in her solitary protest, and the person she actually connects with is the one she’s politically opposed to who spends three days in an office with her—the secretary at the senator’s office. So I like to think my stories explore the differences between easy and effortful connection through technology.

I admire how directly you address race—for example, in “Lightest Lights Against Darkest Darks” and “Local Honey.”

Because of the way I grew up, I’ve been aware of race since I was very small: five years old, traveling across Denver to go to school, and noticing the other kids spoke different languages and had different customs than my family did. Each time I was bused to a different neighborhood, I learned about new cultures and communities. Many of my teachers were BIPOC, and so through them I was brought up knowing about Denver’s role in the Chicano rights movement, learning songs from the Civil Rights movement, and hearing stories my second grade teacher told us about the ancestral Puebloans. Because of my background, I guess, when I come up with an idea for a story, it’s rarely about white characters interacting in isolation.

As I understand it, some white people are not as hyper aware of race as I have been my whole life. From my vantage as a book reviewer, it seems like the main response of white writers to this moment is to avoid talking about race, by setting their work in time periods or locations that only have white people, or writing with a kind of minimalism that allows them to elide mention of BIPOC characters in diverse settings. Jess Row writes about this in White Flights. He points out how odd it is, really, that many of the most celebrated white writers who set their fiction in cities with diverse populations only feature white characters. He asks if minimalism being the most acclaimed literary style is in part to blame, and he writes of Gordon Lish’s famous editing technique, “his aesthetic so easily translates into a radical practice of shame, rooted in the white body, that makes it so difficult for white writers to recognize race at all.”

I think some white writers are afraid of getting something wrong or hitting a false note if they were to include BIPOC characters. But I think leaving them out, and pretending they don’t exist in the world your story is set in, is the greater fault. So maybe I’m stupid in blundering into writing with a diverse cast of characters. I try so hard to do it respectfully, without appropriating or making the BIPOC characters exist only as props in the white character’s story. It’s up to readers to judge whether I did a good job of it or not. But I’d rather err on the side of including diverse characters in my writing than in excluding them.

I think it’s straight-up weird for writers who live in a diverse country to write fiction that makes it look like only white people exist. Many of the writers who do this would call their style of writing “realism,” when in fact, it’s fantasy, and not the good kind with dragons and wizards.

Probably because I am a mom, I love some of the moments in your stories when the main character gives advice. What do you think of your “mom” moments in your stories?

I first wrote most of the stories in this collection a while ago, and it’s hard to remember how I created them, but I just finished a new story that I’d been writing in different ways for probably a decade, and the secret to finishing it was finding its heart. For my writing, until I find the heart—some genuine concern for the humans involved that I hope the reader will share—the story just feels like gimmick. I focus on moms in certain stories because they tend to be the people whose job it is to look out for everyone, to take care of everyone, and love everyone. (We wish it were equally everyone’s job to do this—but statistics about who took care of the kids and educated them during the pandemic don’t bear this out.) Also, I want to write against the notion that moms are boring to read and write about. The moms in my stories aren’t heroic—they are mostly foolish and misguided—but they are always trying, and their hearts are in the right place.

Short story collections and authors don’t receive much love. Upcoming writers are often advised not to write collections and short stories, but so many wonderful writers have built from short story collections, or only had short stories, like Deborah Eisenberg, Alice Munro, Stuart Dybek, Andre Dubus and Lucia Berlin. I know you are a novelist, as well as an essayist and short story writer, but do you have any words of wisdom for short story writers? What do you think you can do with a short story that you can’t do with a novel?

I love short stories, because they capture potent, distilled moments from their characters’ lives. They often provide the opportunity to take risks, in form, subject matter, and language, in ways that might be hard to carry off in longer works.

I love short stories, because they capture potent, distilled moments from their characters’ lives. They often provide the opportunity to take risks, in form, subject matter, and language, in ways that might be hard to carry off in longer works.

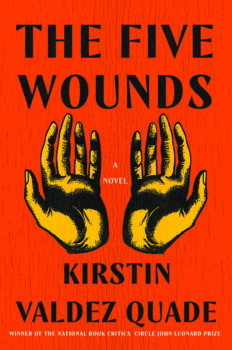

To learn about the differences between the two forms, I loved reading Kristin Valdez Quade‘s story “The Five Wounds,” and then reading the novel of the same name. In the story, her characters were brash and bold, and the plot came together in this dazzling climax with Amadeo Padilla portraying Jesus in a New Mexico town’s reenactment of the crucifixion. The story felt like the big finale of a fireworks display. The novel takes the same characters and expands them—we see them as more vulnerable and nuanced as the book unfolds. It takes the story’s culminating climax—the crucifixion—and portrays it early on, so that the novel is about characters dealing with consequences that were set in motion that day. I love both forms, but they each have distinct rhythms, and that’s why I think it’s important for writers and readers to keep embracing both.

One of my favorite things about you is how much you submit and how on top of open calls for submissions and contests you are. You have a great essay “Why We Write: The Ham-and-Egger” (Poets & Writers, Jan/Feb 2011), but what advice/tools do you suggest for writers to help them publish their short stories?

A good tool to start with is Erika Krouse’s journal list. It gives you an endless supply of journals at which to throw your stories. This list focuses more on legacy, “prestigious” journals. But what I find really invigorating these days is how many more avenues there are to becoming a published writer outside of this standard route. Our friend Gessy Alvarez has built a following for her journal Digging Through the Fat, and has published her flash fiction in places including Drunk Monkeys, Entropy, Bartleby Snopes, and other online journals that you might not find on those standard lists that start with The New Yorker at the top and march through the Georgia Review, One Story, and places like that.

That’s one of my main pieces of advice for people who want to publish their short stories—find someone who is maybe not famous yet, but who is doing great work, and go and see where they’ve published. When Hillary Leftwich was my student at the Mile High MFA, I directed her to Gessy’s website to find new ideas about where to submit. Hillary didn’t need much of my advice—she was already a well-published writer and now she has one book and another on the way.

Speaking of Entropy, Justin Greene writes an invaluable “Where to Submit” column once every three months. I think I might have found the information for the contest my story collection won through it. I guess if I were to boil down my advice, it’s to go and find people who are making fascinating art and putting a lot of energy and generosity out into the literary world, like Erika, Gessy, Hillary, and Justin, and see if you can get any ideas from what they are doing.

Because you’re such an excellent reader and reviewer, I have to ask which authors/books have been most influential in your development as a writer. What is part of your essential reading?

Now you’ve gone and asked a question that’s going to make this book reviewer’s head explode. I am just a fan of books. I love to read books in so many different styles, from minimalism to maximalism, from traditional to experimental, from literary to crime and speculative, from small press to mega press. Sometimes I read pronouncements on Twitter like, “Let’s face it, there’s no reason a book should ever be 500 pages long,” and I always think, of course there should be 500-page books. And fifteen-page books. There should be every kind of book. And send them to me.

If you had to pin me down to name my favorite contemporary writers—oh, the agony of this choice!—I’d have to say Louise Erdrich, who I think should win the Nobel Prize in Literature, Zadie Smith who I’ve been reading since her first book, Colson Whitehead, who pretty much is Mr. Everything at this point, and Jesmyn Ward, who is Ms. Everything.

If you had to pin me down to name my favorite contemporary writers—oh, the agony of this choice!—I’d have to say Louise Erdrich, who I think should win the Nobel Prize in Literature, Zadie Smith who I’ve been reading since her first book, Colson Whitehead, who pretty much is Mr. Everything at this point, and Jesmyn Ward, who is Ms. Everything.

Oh, and Edwidge Danticat. I once was in Santa Fe, and I saw Edwidge Danticat walking with her family on the sidewalk as my husband was parking our car nearby, and I made some kind of distressed yelp like people who are really into Hollywood celebrities make when they see their favorite one. I tried to explain how awesome her writing is to my kids. My son didn’t really understand my explanation of who Edwidge Danticat was to me. So my daughter told him, “Mom’s like a fan girl for her.” I didn’t bother her because she was with her kids. But then the next day, we waited in line for three hours to get into Meow Wolf, and when we were in the middle of Meow Wolf, I saw her again. At this point, I felt the universe wanted me to make a declaration of my fandom. So I said hello, told her how much I love her writing, and our husbands talked in French, that sort of thing. Now that’s my favorite sentence in the English language: “I once encountered Edwidge Danticat in Meow Wolf.” I utter this sentence whenever possible.