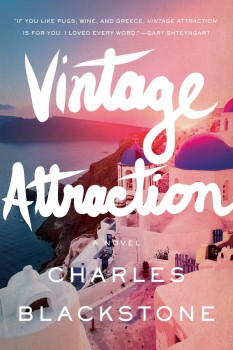

On the surface, the line between fact and fiction is as foggy as one of the wine hangovers in Chicago author Charles Blackstone’s new novel, Vintage Attraction (Pegasus Books, 2013).

The novel’s narrator is a Chicagoan, a writer, and part-time English professor who falls madly in love with Izzy Conway, a master sommelier and local TV food critic, before the two embark on a wine-soaked, pug-laden romance that takes them from the streets of the Windy City to the Grecian countryside.

Blackstone has taught English before. He is a pug enthusiast. He is married to master sommelier and Chicago culinary icon Alpana Singh. But where real-life ends, Blackstone’s novel picks up, transporting the reader through an imaginative and gorgeously rendered exploration of travel, food, and wine culture that fuels a daydreamy relationship built on excess and desire.

Blackstone is also the author of the novel The Week You Weren’t Here (Dzanc and Low Fidelity Press, 2005) and editor of the anthology The Art of Friction (The University of Texas Press, 2008), a collection of writing that examines the boundaries between fiction and non-fiction. He is also the managing editor of Bookslut, an online magazine and blog of book reviews and news.

Interview:

Nick Ostdick: One of things I found so enchanting about Vintage Attraction was your ability to let these characters experience embarrassment, particularly the way our protagonists Peter Hapworth and Izzy Conway leap headfirst into a relationship yet still remain genuine and irony-free. Do you find it difficult to relinquish control of your characters?

Charles Blackstone: It wasn’t difficult for me, since it’s how I’ve always said it’s supposed to go. I’ve always worked in limited POVs, and to have a limited POV means you’re living and experiencing as the character. There’s no room for the author to intrude. And I should probably say at some point that fiction means emotional nakedness.

How it’s supposed to go? Does that mean you intuited your way through much of the novel?

It was a really difficult process, and after the first draft it became even harder to find characters, strangely, or fittingly. I’ve never thought about story as much as I did with these characters early on, and so the telling was, I guess, somewhat easy, but I struggled with voice, with characterization, and, I suppose because of that also with story, as the drafts went on. The first draft was about 800 pages long. Maybe that means I was working kind of gut-instinctively.

Your debut novel, The Week You Weren’t Here, was published in 2005. Were you working on this novel exclusively during the eight years between?

I was fucking around with a manuscript (one I began in high school in 1994, and still want to see if I can make something out of) between 2005 and the end of 2008, which is when I began drafting this one. But I’d had a note about a hapless academic and a celebrity sommelier as early as 2007. (I still have the MacBook sticky note sentence I put down then.) And then I took notes for the Greek trip in March 2008, but did nothing with them or anything until the end of the year. This is unusual for me. The other books have not had that kind of gestation.

I was fucking around with a manuscript (one I began in high school in 1994, and still want to see if I can make something out of) between 2005 and the end of 2008, which is when I began drafting this one. But I’d had a note about a hapless academic and a celebrity sommelier as early as 2007. (I still have the MacBook sticky note sentence I put down then.) And then I took notes for the Greek trip in March 2008, but did nothing with them or anything until the end of the year. This is unusual for me. The other books have not had that kind of gestation.

One of the novel’s greatest strengths is the manner in which the close of one chapter vaults you into the next, which is unlike a number of novels I’ve come across recently where each chapter functions like a short story. As a writer of short fiction, I’m curious how you create the feeling propulsion and maintain it throughout?

I think it is too easy to look at a novel chapter as a short story, and while there are probably certain useful elements that one form can lend to the other (in either direction), the novel, to me, is one long story, and the chapters should function more as the scenes in a short story would, but not as individual stories. I think the trick also is to not have so many subplots and Friends-like casts of protagonists that you have no choice but to turn the chapters into self-contained short stories.

I think a lot of people would like my work to have multiple points of view, to explain the protagonist a little better, but I don’t have the mind for it. Also, I feel multiple POV characters in a novel presents a mode of viewing the world that isn’t really authentic. Typically in life we only have access to one perspective. If fiction is about particularizing experience, it should be very limited in scope, I would think.

Early portions of the novel paint Hapworth’s conflict in trying to be a serious, concerned academic in a culture that doesn’t seem to value academics, especially adjuncts and part-timers. How much of this was intentionally inserted as a reflection of your feelings on the subject, and how much crept in on a subconscious level?

It’s a reflection of how I felt when I was in it, years ago. I managed to escape. I think I got out early, but most probably only last a few years out of grad school. But I wanted to tell the story of a character who can’t get out of it. There’s no tangible benefit to his adjuncting at his age. And I think the farther I’ve gotten away from [adjuncting], the less I get it, so that distance probably led to an even more absurd rendering.

Given what you just said about how this book fermented, is it safe to say achieving some kind distance from what you’re writing about is important to render it truthfully?

I think as far as the telling goes, you have to be able to zoom in and out. To get close to the character who’s in the moment, the distance will have to collapse. And if you’re drawing from life, I think distance is important in determining what events are actually interesting enough to recreate in prose. That thing about tragedy plus time equals comedy comes to mind. Even if you’re writing close to the events and don’t have much distance, the process of revising, especially if it’s a lengthy one like mine, will help determine the soundness of the choices, too.

You’re a managing editor at the online literary-culture website Bookslut. I imagine there’s a constant push and pull between your duties there and the need to get your own words on the page, right?

I make the biggest mistake of all time, the one we tell students all the time never to make, which is to wait for inspiration to strike—at least in terms of beginning a new project. But once something gets going—I’m always a little amazed that I’ve ever been able to get anything going, given the long stretches of nothing-going—I don’t have a hard time finding the time.

I make the biggest mistake of all time, the one we tell students all the time never to make, which is to wait for inspiration to strike—at least in terms of beginning a new project. But once something gets going—I’m always a little amazed that I’ve ever been able to get anything going, given the long stretches of nothing-going—I don’t have a hard time finding the time.

Bookslut is good because there’s a little to do each day, throughout the day, mostly in the form of emailing, and then there’s a lot for me to do toward the end of the month, when we have to get all the copyediting and formatting done for the next month’s issue. I had a draft of Vintage Attraction before I began working at Bookslut, but definitely there was revision going on—sometimes with deadlines—at the same time there were Bookslut deadlines. The answer, perhaps, is not being afraid to get up at four in the morning.

As managing editor, you must see a good number of novels come across your desk for review. Did that at all impact your thought-processes or creative consciousness as you finished and edited the novel?

Yeah, I think I was definitely more aware of the business of publishing while drafting this one. It becomes very hard to ignore the often unpleasant realities of the marketplace. There are so many novels published what seems like every hour, and at this point in my career, it would be really difficult to say, Oh, who cares, I’ll write whatever I want, it will be brilliant and transcend every obstacle. I’m not Donna Tartt or Jennifer Egan. And this is another thing I guess I’ve learned from seeing the book publishing process from the book-review-publication’s-managing editor’s-side of the proverbial desk: you have to know who your peers are, know the similar books being published today. You have to have titles that are your book’s peers (and ideally ones that have sold well) by authors at your level, both in terms of skill and in terms of marketability. To say your comp titles are novels by Hemingway and Faulkner might be a pleasant grad student fantasy, but it’s not going to help get a book published (or survive once published) in reality.

Chicago culture publication Newcity recognized you as part of their annual “Lit 50.” I assume you’ve been witness to the city’s transformation into a literary capital in the Midwest?

It definitely seems like Chicago and its people do care more about literature these days. There’s all the new indie publishing, and writers from across the country are including Chicago on their tours, and there are a lot of inspiring youth literacy initiatives. You didn’t see that fifteen or twenty years ago. And then for a while it was the opposite, these $450-a-ticket fundraisers or Junot Díaz in for one night and 500 people waiting on line to get in. Sadly, the zines and local journals I remember picking up, and in which I discovered some really powerful fiction as a teen, stories I still recall today, have vanished. And there’s no serious book coverage in any of the Chicago papers and magazines anymore except for Newcity and the Tribune.

But I don’t think that’s indicative of much more than one medium’s obsolescence. I had really terrific turnouts at the events I did in the city and the suburbs in the fall and winter, so it’s safe to say that the readers in the city are, in fact, reading and supporting literature.

You’ve done a good deal of touring and promotion for this novel, and I’m wondering if you’re one of those writers that lament this stage of the process or someone who embraces it and thrives on it?

I like doing events. I’m not one of these writers that thinks he doesn’t have to go on Facebook and Twitter and give readings and go to book clubs and Skype and answer random people’s email. Writing is only a part of the job of being a professional writer.

Has feedback from audiences or readers impacted your thoughts on the novel?

Has feedback from audiences or readers impacted your thoughts on the novel?

This is something I’ve thought a lot about. Obviously most readers will encounter a novel once it’s too late to change anything. The same isn’t exactly true in other arts. A chef can change ingredients and preparations and take dishes off a menu. A ballet dancer can, I don’t know, change the direction of a croisé for tomorrow night’s performance. Even filmmakers can recut and reshoot after a screening.

I guess we have a similar process in revising before publication, but it’s asking a lot more of someone to read your 800-page first draft than it is to watch a 90-minute documentary.

Speaking of first drafts, what are you working on now? What’s next for you?

I haven’t really been working on anything, not seriously, since Vintage Attraction came out (and probably for months leading up to that point), because I wanted to focus on publicity. Publicity is important—and the author is largely responsible for making sure it happens. I didn’t want to divide up my time any more than I already do with everything else. But now that I’m largely done with events until the paperback comes out in October, I think I can finally get my head back to work. There’s a character I haven’t been able to get right in the past, since I was a teen in the 90s, actually. She keeps trying to get me to write her, so maybe I should start listening.