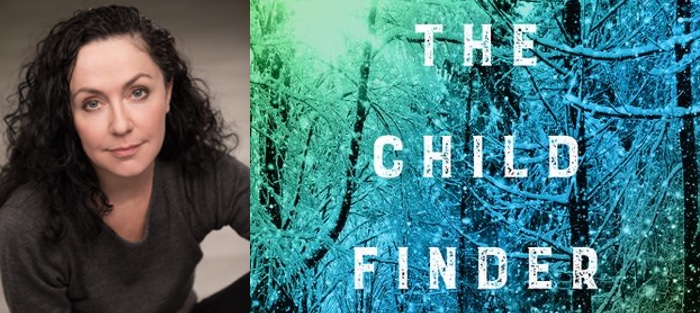

I picked up Rene Denfeld’s The Child Finder (HarperCollins, 2017) after it was enthusiastically recommended to me by another author. In it, I got the gripping page-turner I expected, but was also blown away by Rene’s complex and hauntingly beautiful prose, so much so that I felt compelled to quote numerous passages to my husband as I read.

The Child Finder tells the story of a missing eight-year-old girl who endures her abduction by channeling her own imagination. Set in a mysterious forest in Oregon, the book is rich with psychological insights as it alternates between the point of view of the child abductee and the investigator—who has her own traumatic past—hired to find her.

Rene’s first novel, The Enchanted (HarperCollins, 2014), garnered numerous prestigious awards, including the French Prix, an ALA Medal for Excellence, a Carnegie listing, and an IMPAC listing. The Child Finder, her second novel, has become an international bestseller.

Rene is a former journalist and a licensed investigator specializing in death penalty work and sex-trafficking victims. Her articles have been published in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Philadelphia Inquirer. She received the Break the Silence Award in Washington, DC in 2017 for her social justice work, and was named one of the heroic stories of the year by The New York Times. She is the mom of three adopted foster children and fosters others. She lives in Portland, Oregon.

Rene and I conducted this interview via email.

Interview:

Kate Lemery: How old were you when you first decided you wanted to be a writer? What sorts of things did you write?

Rene Denfeld: I’ve always wanted to be a writer but thought people from my background couldn’t be writers. I grew up in severe poverty as a young child and experienced a lot of trauma. I’ve written about my stepdad—he’s a registered predatory sex offender. By the time I was 15 I lived on the streets. So, I carried a lot of this shame and lack of belief about myself.

Luckily, I discovered libraries. Books became my sanctuary. Eventually I realized that the poetry I heard inside my head could come out on the page. I wrote my first poems on a typewriter I bought for a few dollars from a local thrift store after I escaped the streets. But it still took a long time for me to feel confident enough to write a novel.

What made you decide to become a reporter early in your career?

What made you decide to become a reporter early in your career?

I started by writing for alternative newspapers, you know, the kind that pay ten dollars for a story. Through hard work I made my way up to freelancing for papers like The New York Times Magazine. I learned a great deal of craft from my years in journalism. I learned structure, narrative, voice, research, investigations, how to get edited and more. I also learned how to write on a deadline! For me it was an effective way of becoming a writer without a degree. But then the bottom fell out of the journalism industry. By that time, I had adopted three kids from foster care and was fostering others. I really needed a day job. I decided to go into social justice work—it called to me. So, I took my skills as an investigative reporter and became a licensed investigator. I specialize in death penalty work, including exonerations, as well as working with sex-trafficking victims. I know it’s an unusual job for a writer, but it really has worked for me. I became licensed in 2006 and have worked hundreds of cases, including a stint as the chief investigator for a public defender’s office. I’ve done political asylum work, immigration cases, you name it.

Because of my background I feel a strong drive to help others, so that job change made perfect sense. I won’t lie, it hasn’t been easy. I’m a single foster adoptive mom with a super stressful job. Cases, caseworkers, calls, IEP meetings, clients, trials, witnessing injustice, endless visits into prisons and jails, helping my kids in therapy—it can feel my life is soaked in trauma. At the same time, it is deeply rewarding. I love my life, I love my kids, I love feeling I am doing something meaningful. I did this for several years and didn’t write anything. Then one day I was leaving the death row prison in our state and I heard a voice. He said, very distinctly, “This is an enchanted place.” That magical voice led to my first novel, The Enchanted. It was like a fever. The words just poured out on to the page, and it felt all I had experienced and learned came with them. I knew then I had found my calling. I feel very lucky to have a life where I have found my three callings: social justice work, foster parenting and writing novels.

It took a few years of writing before I first considered myself a “real” writer. When did you first think of yourself as a “real” writer?

What is a real writer? I get confused when people say that. We are either all real writers or none of us are. Given all the barriers to writers from marginalized backgrounds, I guess my alarm bells go off. There’s an interesting discussion to be had around the entire concept of realness. Who gets who to be real in our culture, and what does that mean for those who are not seen as real? Women in particular get a lot of messages about who is a “real” woman, based on everything from our looks to private decisions about parenting. As a long-time foster mom, it reminds me of all the times people say “real” mom in front of me. I’ve been told I am not the “real” mom, to which I reply I’m pretty sure I am not imaginary. If you write, you are a writer. And personally, I thank each and every one of you for writing. We need your voices.

I met you through an online community of writers, where you frequently provide thoughtful advice from your hard-won experiences as an author. You also routinely champion the work of other writers. Do you have a personal philosophy on literary citizenship?

Thank you! I do it because I love it. It makes me feel good to champion other writers. It’s hard to be a writer, it’s hard to be a good person, and being there to help others seems like an easy way to do something nice. Plus, what are we without each other? I was lucky to find support when I was an aspiring writer, and still feel blessed to know so many wonderful, talented writers. I don’t really have a philosophy on it except to say that bitterness is the enemy of art. If you are an asshole it will come back to you. When I was a much younger writer I was, at times, a real asshole. I wrote things out of anger that I had misplaced. I really regret that and feel tremendous remorse for it. I wish I could go back in time and take it all back.

Why did you choose Oregon’s Skookum National Forest as the setting for The Child Finder? What is the role of nature in your book?

Nature is a character and a place. My novels are stories of wilderness, even when they are set in captivity or a prison cell. I’m enthralled with the beauty of the world, even in hardship. I think we hunger for connection to nature, even if it is a walk in a city where we see birds in the trees, or a breeze in a window. The physical world is important to us, and sadly often depicted as spiritual instead of fundamental. We need nature. It’s not about being virtuous enough for nature, or purchasing a vacation where we consume nature. It’s about our innate need to feel alive. We ask the world to respond to us and it does. That’s a miracle right there.

The Child Finder has been compared to a fairy tale for adults. Can you talk about the element of fairy tales in your book and why you use that as a theme?

My favorite stories as a child were fairy tales. Where else can you find children trapped in dungeons, roasted alive in ovens, kidnapped and held by monsters, only to find a way to survive? I felt those stories were written for me. In fairy tales even the most traumatized child has hope.

The child in The Child Finder escapes into her imagination to survive, as I think many of do. She uses fairy tales to come to believe she is a character called “The Snow Girl.” I wanted to explore the role of imagination in what we call resiliency. I think we don’t pay enough attention to the power of imagination as a survival tool. If you have an imagination no one can take it from you. It is a radical act, to declare your right to imagine. In my justice work it is the difference I see between those who survive and even thrive despite horrifying trauma, and those who succumb to rage and destruction. The ones who survive are those who can imagine themselves in a different future. The same is true with children. Those who imagine survive. As a child living with sex offenders, I escaped into a world of make believe. It saved my life.

Which part of The Child Finder was the hardest for you to write?

I wouldn’t say they were difficult, but the scenes of abuse took a lot of tears. Because of my history, I have strong feelings about not writing violence in ways that are exploitative or graphic. Abuse is not there to titillate the reader—there is way too much of that already. My rule is a writer is to imagine myself turning over the pages to the fictional victim. I ask them, “How do you feel about how I portrayed your pain? Did I honor and respect you?” It is extremely important to honor and respect the dignity and privacy of victims. That includes fictional victims.

In an earlier interview, you said that you feel poetry comes out when one truly channels another person, and that this is important to you as a writer. What did you do to be able to channel the feelings and thoughts of Madison? And what did you do to channel the thoughts of B, a middle-aged child abuser? Why did you choose to channel those two voices? Do you have any advice to writers for how to channel characters who aren’t immediately sympathetic?

First, I think we have to drop the idea some people are more earning of sympathy. We’re all complicit, we all have responsibility for the world we shape. There’s been this hierarchy in literature where privileged white people are assumed to be good, and poor, POC, and others are assumed to be bad. I think we need to turn those tropes over. For example, there are so many negative stereotypes of foster kids and foster parents in literature. Want an evil bad seed or troubled child? Make him a foster kid! Want an abusive, money-grubbing welfare cheat? Make her a foster mom! The truth is foster kids are in the system because of factors outside their control—such as immigrant policies and mass incarceration—and foster parents like myself are often good people. Most foster parents are single working-class moms, and many of us are women of color. That’s why we are favorite targets. It’s not because we are welfare cheating abusers. It’s because we are working-class single moms, many of color, and that makes us suspect and hated. It has nothing to do with the truth and everything to do with racism and classism. Likewise, foster kids are not all junior sociopaths. I recently took in a new teenage foster and I love her. My kids are awesome!

In the words of Tayari Jones, we need to interrogate ourselves as writers. We need to ask why we choose the characters we do and what we are trying to communicate with them. We need to challenge our own biases. One of the characters I loved writing in The Child Finder was Mrs. Cottle, a long-time foster mom. Likewise, the heroine Naomi was in foster care and she is a good person, too. It felt natural to me to channel Madison, as I had similar experiences as a child as the victim of pedophiles. And as someone who grew up with attachments to the pedophiles in my life, I also felt I could get close to B. I suppose if I have advice to writers on channeling characters, it is to start by asking yourself why you are writing the character. Make sure you feel you can genuinely access their humanity and tell the truth of them even if it bucks the stereotypes.

From now on, I’ll always think of The Child Finder when I see Hungry-Man frozen dinners, which are a special treat B purchases for himself and Madison. Many of us (myself included) grew up eating these, and in your book, they seem to be a metaphor for the comfortable, safe, cozy life that B would have wanted for himself. Is that intended, and do Hungry-Man frozen dinners have any special personal associations for you?

I grew up eating poor. Fried baloney, margarine sandwiches, the free lunch programs at school. This is the reality of life for many, and I want to show it in a respectful and honest way. Now I spend a lot of time with poor people as part of my job in public defense. In Oregon that tends to mean a lot of rural poverty. So, I spent time in communities where there is no library, no doctor, no dentist, and the local store gets a shipment maybe once a month—that’s if the roads are clear. For me, as a kid, nothing signified a special treat more than a Hungry-Man dinner. That or one of those gluey little frozen pot pies. Ah, memories!

I know that you’re a voracious reader. Are there any books you’ve recently taken the time to read twice?

I’m someone who reads favorite books dozens of times. That’s not an exaggeration! I’ve read The Woman Warrior so many times I can recite it. If I ever meet Maxine Hong Kingston, I’ll probably scare her to death by reciting her own work at her. I read everything from memoir to essays to fiction. Let’s see. I loved, loved Red Clocks by Leni Zumas. There’s a novel coming out called The Dream Peddler by Martine Fournier Watson that is so good. The Great Believers by Rebecca Makkai is worth a dozen reads. I loved Andrea Jarrell’s memoir I’m the One Who Got Away and Alice Anderson’s Some Bright Morning I’ll Fly Away. There are a lot of books that get marketed as genre that I think deserve more literary recognition. Gilly Macmillan is a good example. She’s really good. Oh, and I think Survivor Cafe by Elizabeth Rosner is one of the deepest, most brilliant nonfiction books on trauma ever. It should be taught in every school.

What is something your readers would be surprised to learn about you?

I’m a very friendly, laughing, joy-filled person. People often assume that with my work and life I’m a ball of stressed out gloom. Instead I tend to be full of laughter. I take positive joy in my life and my opportunity to help others. I feel so lucky to be alive, to be creating and loving others.

I know you’re very private about your writing in process. Would you be comfortable saying whether you’re working on fiction or nonfiction?

My next novel should be coming out in a year or so. It’s called The Butterfly Museum and it tells the story of Celia, a 12-year-old street girl, surviving on the streets thanks to her unshakeable belief in the power of butterflies. I can’t wait to share it with you!

That sounds great. Thank you, Rene. You’ve given me so much to think about.