Editor’s Note: In celebration of our ten-year anniversary last fall, we decided to curate an occasional series of “From the Archives” posts. Some of these features are editor favorites, some tie in with a new book out from an author whose worked we’ve covered in the past, and some are first conversations with debut authors who are now household names.

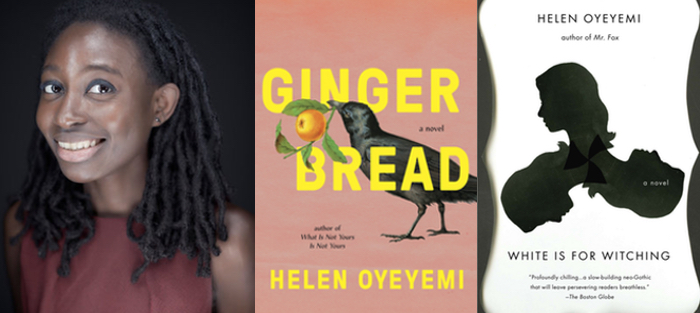

This week we’ve returned to Neelanjana Banerjee’s interview with Helen Oyeyemi, which was originally published on March 16 of 2010. Oyeyemi’s newest novel, Gingerbread, is out next week from Riverhead.

To say Helen Oyeyemi’s latest novel, White is for Witching (Nan A. Talese / Doubleday), reinvents the Haunted House story would be a vast understatement. Oyeyemi manages to dismantle and rebuild the haunted house narrative brick-by-brick, creating a book filled to the rafters with innovation. The novel attempts to unravel the mysterious disappearance of Miranda Silver, a young woman in Dover, England, who is afflicted with a rare eating disorder that compels her to eat only inedible substances, and with living in a house that has a mind of its own. But for all its terrors—there are scenes that will make your skin crawl with fearful delight—Witching is also a book about the weight of ancestry, the nature of xenophobia, and the impossibility of saving the ones we love.

At twenty-five, Oyeyemi has established herself as a writer in control of both the supernatural realm and stories of young British women dealing with the often upside-down real world. Her first novel, The Icarus Girl (Doubleday), was published to great acclaim during her first year at Cambridge University. The Icarus Girl tells the story of Jessamy, a bi-racial Nigerian and British girl who meets a magical friend named Tilly Tilly on a visit to her grandfather’s compound in Nigeria. Jessamy invites her new friend home to London, where things go terribly wrong. Her next book was The Opposite House (Anchor Books), about a young Cuban woman, Maja, living in London and trying to negotiate her past and her future, and the intersection of her story with that of Yemaya—a Santeria emissary living in a parallel spirtual world.

I met Oyeyemi when we were both in residence at Hedgebrook Writing Retreat on Whidbey Island in Washington, where she won me over with a short story about a girl in a wedding dress and a probably-dead boy. We conversed across many time zones (she in Cambridge, myself in San Francisco) on the magically real wonder of Skype.

Interview

Neelanjana Banerjee: When I first met you, I was prepared to dislike you (and your writing) for being a child prodigy. Do you ever feel like you have to defend yourself as a young writer in the publishing world? Does it affect the way you have to present yourself?

Helen Oyeyemi: No. I think it affects the way I’m reviewed. I’ll read reviews and I’ll know they’re coming at it from a sort of “Oh, well done, you can write” kind of thing. Or there are people that just evaluate me on the whole youth thing, and hopefully that’s going to go away because I’m actually quite old now.

The story of your first book is somewhat legendary: you were eighteen years old, secretly writing the novel that would become The Icarus Girl, and when you had some twenty pages, you sent them to an agent you found in the phone book. Is all that true?

It was really to get advice and was just curiosity to see whether, I don’t know, if [the writing] was going to turn into something eventually, because I only did just have those first twenty pages. So it just wasn’t a serious inquiry. I thought, “Well, if he tells me I can write, then I can sit on it and do something later.” But he was quite urgent about it in an exciting way and I guess that’s why all this happened.

It was really to get advice and was just curiosity to see whether, I don’t know, if [the writing] was going to turn into something eventually, because I only did just have those first twenty pages. So it just wasn’t a serious inquiry. I thought, “Well, if he tells me I can write, then I can sit on it and do something later.” But he was quite urgent about it in an exciting way and I guess that’s why all this happened.

Had you written a novel before that?

I had lots of short stories about [the character] Tily Tily. They were really quite short and quite bad. Tily Tily would just show up and ruin someone’s life and then leave pretty quickly. The beginning of The Icarus Girl was the best shot I’d had at the whole Tily Tily thing.

I think your work is fascinating. As a person of color and an immigrant, your books really speak to me because of the fresh ways you tackle issues of being bi-cultural. Where do you think the origin of your style came from?

I’m not quite sure. It’s not really what I want to write about. I’d rather write a heart-warming tear-jerker or romance or something just nice, but it doesn’t work. These two things just keep coming out, the immigrant thing and the supernatural thing. But I don’t process consciously. I do like reading [supernatural narratives]. I like imagining that sort of stuff. I find ordinary realist narratives just lacking in something, like realist narratives just aren’t real for me. They don’t make that much sense. Whereas reading stories in which the world suddenly changes, I’m like: “Yeah … that makes sense.” Strange mental states, all that stuff, just seems to be a more–not an honest way–but a more interesting way of describing the world.

I recently saw the writer Dan Chaon (Await Your Reply) at a reading and he told a story about a creative writing class in college where he turned in a “genre” story and was told: “This kind of writing is not accepted here.” Have you ever felt that people take your writing less seriously because it is not a “realist narrative”?

I don’t really think of it as speculative or genre writing, and I think I’ve been quite lucky that people haven’t labeled it that way either, but maybe it is just because of being black and being an immigrant, to be honest. So they’ll go, “Oh, it’s just magical realism.” And just try and maneuver around the fact that a lot of crazy stuff happens. They’ll be like: “She’s talking about something else, a whole other experience.” When really I’m saying, there actually is this racist house. It can be more easily read as a metaphor when you’re talking from the standpoint of an “other,” so it’s probably easy to get away with it if you have another identity issue going on.

Reviews of White is for Witching especially [in England] have been kind of wishing that it would not be about the supernatural and that I would just get down to the nitty gritty of immigrant life. While reviews in America and Canada have been like “Yeah, the supernatural bit is great, but maybe there is too much of a political agenda.” I can’t win. [Laughter]

Speaking of magical realism, would you ever use that term to describe your work?

No, I wouldn’t. I think there are so few books that it actually even applies to. I’m starting to think it’s actually only [Gabriel Garcia] Marquez that it applies to. Even Isabelle Allende doesn’t really write that, whatever that is. I don’t write [magical realism]. I just call what I do stories.

In all of your books, there are some really scary parts and horrific moments. I was surprised because I feel like I haven’t experienced that frightened feeling while reading since I used to read Stephen King when I was in middle school. It made me realize I miss the sensation. Is there a special process to writing frightening narratives?

It’s hard to say. But when writing it, I am conscious of wanting to be affecting in that way. So there are points of the story when I’m like, “Ha! Ha! Ha!” [Sinister Laughter], when I was writing and feeling really good about it, because I was freaking myself out. So I hope I’d be freaking other people out as well. Just like you with Stephen King, I remember reading him and being like: “Oh my god. I can’t believe what is being done to me.” And that was fascinating that there was like a whole technology to it. He handled the story so well that he could suddenly cut you, and then withdraw and keep going. I’d come to Stephen King after reading some heavy existential texts, and it was just a whole other way of seeing what a book could do. Poe, as well, is another great master.

Another of my favorite parts of your writing is your ability to explore reality on all these different levels. The characters are dealing with certain supernatural occurrences, but then also dealing with being young people in 21st Century Britain. For example, Maja’s younger brother Tomas in The Opposite House, is dealing with racism in a very real and sometimes hilarious way. At one point, when describing a fight at school to Maja, he says of his classmates: “[B]ut they were all on my side, because we’d watched Roots in history last week.” In White is for Witching, Miranda is dealing with some powerful supernatural events, but still ends up at the local pub where the girls are described as “all strawberry lip-gloss, halter-neck tops and bare legs.”

Another of my favorite parts of your writing is your ability to explore reality on all these different levels. The characters are dealing with certain supernatural occurrences, but then also dealing with being young people in 21st Century Britain. For example, Maja’s younger brother Tomas in The Opposite House, is dealing with racism in a very real and sometimes hilarious way. At one point, when describing a fight at school to Maja, he says of his classmates: “[B]ut they were all on my side, because we’d watched Roots in history last week.” In White is for Witching, Miranda is dealing with some powerful supernatural events, but still ends up at the local pub where the girls are described as “all strawberry lip-gloss, halter-neck tops and bare legs.”

It was something I hesitated about at the editing stage, but it made the characters that much more real to me. If you’re going to have things swing into strange territory you’ve got to have some sort of foundation that’s at least familiar and “real”—otherwise, everything’s at a certain pitch, which is like “Ahhhhh!”

In White is for Witching, and all your books for that matter, there is a really interesting range of characters when it comes to ethnicity. The main characters in Witching are white British, but there are Kosovans, Azerbaijanis, and Africans. Why did you chose to write the novel from the point of view of Miranda and her family?

Initially, I wanted to write the book about this black family moving into this racist house, but it just seemed far too obvious. I could just see how it was going to go and you don’t want to write when you already know all about it. I thought it would much more interesting to have a girl living in this house that’s essentially poisoning her, and for her to not understand fully what is happening. It seemed a lot more insidious. [This story] says a lot more about the race situation and the whole immigrant situation than just having a black family move in and be instantly repelled–because that’s just not how it is. It’s much more all these little hints and unsaid things; that’s how racism works these days. It just ran alongside my whole idea I’ve been developing about vampires and how vampire stories are really about race. Well, I thought, I’ve got to have somebody who’s part of the dominant group—I could tell it from that perspective. It was a fun, interesting experiment as well, and I wasn’t sure if I was going to be able to do it. Because there were all those times growing up when I was like: “Ahhh, white girls … I don’t know! I don’t understand them. We’re so different.” Then it turned out that Miranda is the character I’ve most related to, because she’s having a crack up, and I’ve had one of those. It was easier to come from that perspective.

What are you reading right now?

I’m reading Hedda Gabbler. I just read A Doll’s House.

Do you read when you write?

I do tend to read after I’ve got the quota done for the day, otherwise life just seems really bleak.

Sometimes I think that being a writer means you never really get to go on vacation. When you finish a book, do you not write for a long time, or do you start on the next one immediately?

After I finished White is for Witching sometime last year, I did take two months during which I was just reading lots and thinking lots, but it was in preparation for the next book. I do think you have to just keep doing it or suddenly it just becomes really hard to get started again.