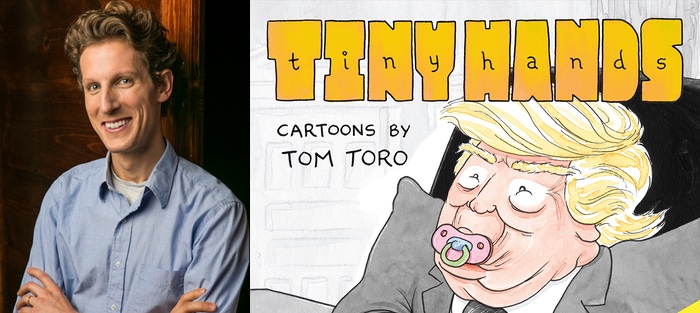

Fiction Writers Review readers may recall Tom Toro’s clever and almost too-close-to-home series of cartoons on the writing life in fall 2016, The Flyleaf. While Tom was already a New Yorker cartoonist (borne of a tough period at home when he decided to go for broke and see how long it would take him to get an acceptance at the venerable magazine—the answer? three years), little did he know that he would soon become their Daily cartoonist . . . during the inauguration and the beginning of the administration of our current president.

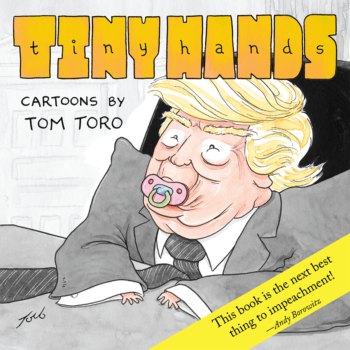

This intense but fecund period of his work has been collected in a wicked little volume called Tiny Hands (Dock Street Press), complete with a blurb from Andy Borowitz on the cover. While the cartoons offer levity and sanity in equal measures, Tom pulls no punches when it comes to his personal opinion of Trump. Here’s how Toro explains the challenge of satirizing the president:

We have a president who is, literally, a clown. (No disrespect to clowns) . . . Trump is a seventy-year-old adolescent who is functionally illiterate and who has been tossed unexpectedly into the most high-stress job in the world . . . It’s raw comedy—it’s the very plot of Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator.

So one of the most fascinating and satisfying parts of Tiny Hands is seeing the first sketches alongside the final published cartoons. This is a book of political satire, but it also reveals much about creative process on a compressed timeline when the stakes are incredibly high.

I talked with Tom via email about his creative process during this period, the political responsibilities of artists, and where he’s going next.

Interview:

Jennifer Solheim: You do a wonderful job introducing us to the atmosphere in which you drew the cartoons for Tiny Hands. Did it feel like you were creating a larger body of work as you produced a new work day after day?

Tom Toro: At the time I was drawing the cartoons, my only concern was responding to the latest calamity coming from the White House or Trump’s Twitter feed. It was daunting enough. The biggest challenge in creating jokes was selecting which disaster to lampoon—there seemed to be a dozen new ones every day. And it hasn’t slowed down, unfortunately, because Trump hasn’t magically grown smarter or more humane. In fact he’s only gotten worse as exhaustion sets in and failures and humiliations mount. But in the months immediately following his ignoble inauguration—which is the period addressed in Tiny Hands—there was still the shock that Trump was actually as terrible as we feared he might be. Outrage fatigue hadn’t yet numbed us. The cartoons were drawn in that state of horror, panic, sleeplessness, despair. It’s nice work if you can get it.

Tom Toro: At the time I was drawing the cartoons, my only concern was responding to the latest calamity coming from the White House or Trump’s Twitter feed. It was daunting enough. The biggest challenge in creating jokes was selecting which disaster to lampoon—there seemed to be a dozen new ones every day. And it hasn’t slowed down, unfortunately, because Trump hasn’t magically grown smarter or more humane. In fact he’s only gotten worse as exhaustion sets in and failures and humiliations mount. But in the months immediately following his ignoble inauguration—which is the period addressed in Tiny Hands—there was still the shock that Trump was actually as terrible as we feared he might be. Outrage fatigue hadn’t yet numbed us. The cartoons were drawn in that state of horror, panic, sleeplessness, despair. It’s nice work if you can get it.

Since I was assigned to do The New Yorker’s Daily Cartoon at the very beginning of Trump’s presidency, I was responsible for setting the tone for how the cartoons would deal with his obliteration of social norms once in office. Finding the thin line of what was permissible, what could pass editorial muster, and selecting from among a depressing panoply of targets, was what occupied my full attention. I’m happy the cartoons did end up forming a cohesive collection—but that’s probably due to Trump’s consistently shallow rancor, rather than any forethought on my part.

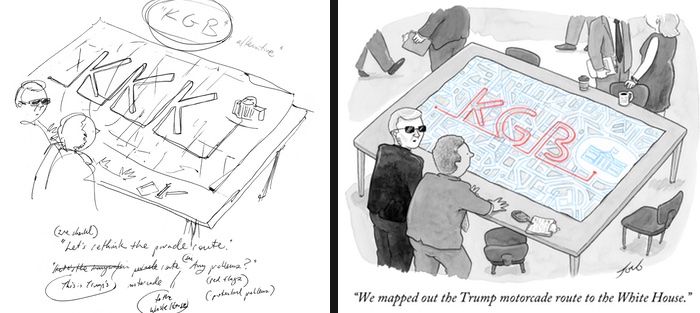

It’s fascinating to see the sketches that served as drafts for the final published cartoons—the differences between the sketch and the final often creates a narrative entirely based on what the reader might infer. For example, there’s the cartoon where they’re mapping the motorcade route in preparation for Trump’s inauguration. In the sketch, the mapped route spells out KKK. In the final, it’s KGB. Can tell us about how editorial decisions were made about this cartoon—and maybe a few others as well? And what was your aim with including the sketches alongside the published versions?

It’s fascinating to see the sketches that served as drafts for the final published cartoons—the differences between the sketch and the final often creates a narrative entirely based on what the reader might infer. For example, there’s the cartoon where they’re mapping the motorcade route in preparation for Trump’s inauguration. In the sketch, the mapped route spells out KKK. In the final, it’s KGB. Can tell us about how editorial decisions were made about this cartoon—and maybe a few others as well? And what was your aim with including the sketches alongside the published versions?

I often struggled to find the balance between jeering and jesting. As Bob Mankoff, The New Yorker’s former cartoon editor, once said, “If something is worth saying, it’s worth saying funny.” But the temptation to poke Trump in the eye, instead of in the ribs, would sometimes get the best of me and I’d need to redraw a gag. The Daily Cartoon is a unique beast because it needs to be topical, like all political cartoons, and yet it also needs to adhere to The New Yorker’s highbrow aesthetic. Common tricks of the trade aren’t available to us, such as labeling stock characters “CEO” and “Labor Union,” or the overt use of symbols and iconography. The joke needs to arise from a specific situation that is, in cartoon terms at least, realistic and believable. The scene needs to feel organic and unforced. Which is very difficult to achieve in an ideal situation, let alone under serious time pressure.

Sometimes I’d fail, and the editors would have to punt me back into fair territory—such as when I submitted mock-ups of Trump 2020 campaign signs with the 0’s as nooses, or as eye holes in a Klansman’s hood. (Who knows, those ideas might seem tame by the next election cycle.) I wanted to include the sketches of each cartoon because it shows the steps in that delicate process: coming up with an idea and then tailoring it to suit The New Yorker’s standards of etiquette. Besides, it allowed me to show off some jokes that wouldn’t otherwise see the light of day.

This is one of those tedious not-a-question-so-much-as-an-observation questions: your cartoons for The Flyleaf and the others for The New Yorker tend to have a social and artistic bent to them—now you’ve moved into political cartoons, but in all cases your work tends to speak to accountability, whether it’s to oneself, the world, or somewhere in between.

That’s interesting! I’ve never thought about my work in terms of accountability. Perhaps you’re right. This does bring to mind one cartoon—it might have been for The Flyleaf or it might be unpublished, I can’t remember—but anyway it shows a guy lying on the couch with a pad and pen, and he’s saying to his partner, “I’ll start writing my debut novel once I’ve come up with the overarching theme for my entire oeuvre.” I’ve always felt that way about life and work: the burden of expectation. I’m saddled with vaunting ambition. Maybe it’s a generational thing. What seems to define millennial artists is being over-educated; we write the doctoral thesis for our work before we’ve even begun to make it. I take this kind of self-conscious, hyper-conscientious approach to all my work, and I guess I find it distressing when I see people in positions of power, like politicians or business tycoons, behaving without an ounce of caution.

This is kind of an obvious question, but I think it’s an important one for us to reflect on right now: what do you feel is the role of the artist in the Trump era? Do you feel that you have a duty to be politically engaged in your work? And how has that duty changed since Trump was inaugurated?

For the introduction to Tiny Hands I wrote, “Levity alone cannot change the world but it can buoy up the movements that will.” Perhaps not Churchillian, but hey, I wanted to try my hand at pith. I really do believe that sentiment. I know many intelligent, decent, kind-hearted people who ever since the election can only bear to get their news from comedians. The raw reality of Trump’s reign is just too appalling.

For the introduction to Tiny Hands I wrote, “Levity alone cannot change the world but it can buoy up the movements that will.” Perhaps not Churchillian, but hey, I wanted to try my hand at pith. I really do believe that sentiment. I know many intelligent, decent, kind-hearted people who ever since the election can only bear to get their news from comedians. The raw reality of Trump’s reign is just too appalling.

In some ways, satirists like Samantha Bee, Stephen Colbert, and Seth Meyers are able to deliver the facts more honestly than reporters because they hit the right tone of exasperated outrage, leavened with bemusement. They don’t need to adhere to journalistic niceties and create false equivalencies, which in the face of the collapse of democracy seem almost vacuous. That’s what comedy can do at this perilous moment: clarify, empower, galvanize. When people say that it’s a boom time for humorists because we have so much material to work with, I like to reply: may we live in interesting times, but may we outlive them. Comedy can help us survive. It’s the next wave of progressive politicians and community leaders who will rescue us from this national nightmare and create real and lasting change, but it’s the comedians who will help to lift our spirits along the way.

What’s next on your political and artistic agenda, both together and respectively?

Well, this weekend I’m canvassing for Democratic candidate in a state that Trump won by 15 points. Go Hillary Shields, Missouri State Senate! I’m going to see a Hillary win an election if it kills me, damn it. (I live in Kansas City, so it’s a convenient revolt.) Meanwhile, on the artistic front, I’m drawing a cartoon orgy for a special Hugh Hefner memorial edition of Playboy. Dismantling the patriarchy is a tricky process—what can I say?