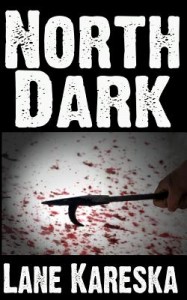

I don’t read post-apocalyptic fiction, but I will read about anything by Lane Kareska. Lane and I were MFA students together at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale. Over our three years in the program, Lane and I met almost weekly outside of class to workshop our own work. We supported each other as our literary voices emerged. But when he told me that he was publishing North Dark (Sirens Call Publications, 2013), a novella, set in sparse futuristic failed state, I all but rolled my eyes. It’s not that I don’t see value in science fiction or the end of human civilization. It’s just that I prefer to consider the puzzles in our current existence. Perhaps it’s simply a matter of taste. But if anyone could convince me that post-apocalyptic fiction can accomplish as much as mainstream literature, it’s Lane Kareska.

North Dark is beautiful, brutal, and brave. I’ll admit to reading some of its violence through splayed fingers, but the action is written with such skill that the painful episodes are digestible and justified. The pace and writing alone kept me reading. If North Dark is post-apocalyptic fiction at its best, the genre may have just won a new fan.

The story is set in a barren, collapsed society. Two Crows, the novella’s main character, abandons his last shreds of safety to pursue a fugitive who destroyed his family. His quest for revenge leads Two Crows to travel by dogsled through frozen tundra, populations dying from plague, and dregs of civilization, meeting violence at every turn.

Lane Kareska was born in Houston, Texas. He currently lives in Chicago where he teaches creative writing and works in technology and new media. His short stories have appeared in Berkeley Fiction Review, Sheepshead Review, Flashquake, and elsewhere. North Dark is his fist novella. Lane and I chatted about North Dark and his evolution as a writer over e-mail and Skype.

Interview:

Melissa Scholes Young: Like Hamlet, Two Crows is motivated by revenging his father’s death. Why is revenge such a universal theme?

Lane Kareska: I like that when you think about revenge, your mind goes to Shakespeare. Mine goes to the Klingons from Star Trek. But revenge is an old idea and it belongs in both oeuvres, and all others. It’s about as universal as it gets, and that’s probably one of the reasons the concept of revenge is what jumpstarts the novella. It’s simple, immediately relatable, clear, and generally kind of a pure notion: you hurt me, and so now I will hurt you. It won’t solve anything, but there’s something primal, unadulterated, and inarguable in the human body that demands it.

Lane Kareska: I like that when you think about revenge, your mind goes to Shakespeare. Mine goes to the Klingons from Star Trek. But revenge is an old idea and it belongs in both oeuvres, and all others. It’s about as universal as it gets, and that’s probably one of the reasons the concept of revenge is what jumpstarts the novella. It’s simple, immediately relatable, clear, and generally kind of a pure notion: you hurt me, and so now I will hurt you. It won’t solve anything, but there’s something primal, unadulterated, and inarguable in the human body that demands it.

Is revenge ever satisfying? Without giving away the ending, is Two Crows satiated in the end?

Revenge demands that you enact a crime similar to that which was committed against you, right? So, in that way, it’s a fascinating idea: the crime committed against you, when avenged, also causes you to be guilty. So the idea of satisfaction is kind of a tainted one from the onset. But, that said, these are not the thoughts with which Two Crows is concerned.

Two Crows is consumed with the idea of avenging his father and his family. He is his mission. Does he achieve that? Is he defeated or dissuaded? I will say that the “resolution” was not at all what I expected; it completely blindsided me and that was how I knew—right or wrong—it was the true ending.

The failed state setting is cruel yet gripping. I’ve read a lot of your writing over the years, but this is the sparsest I’ve ever seen it. Can you talk a little about how you wrote the novella and how your decisions affected the setting?

Yep. The abridged version of the truth is that last winter was the longest of my life: I was in Chicago, not by choice, during a hilariously sustained and cruel season, during which my dog was slowly and inevitably dying of kidney disease. There was a tidal wave of daily medication, regular and expensive specialist visits, and eventually, twice daily dialysis sessions conducted by me. It was awful. And even though it probably extended his life by months, it was clear that it was a stopgap, and not a cure. The only way I could really deal with this was to take my dog, Charlie, every weekend, out to my dad’s secluded cabin in the woods of northwest Indiana and write in really tough, cold, 48 hour sessions.

I think the circumstances, the subject matter of the book, the mood of the winter, and the setting in which I found myself all contributed to, informed, guided and created North Dark. The setting in particular: desolate, tundra-like, shuttered, apocalyptic, all generated the world of North Dark. And it was that setting that demanded the language used. It really wasn’t a conscious choice so much as an inevitability. Another voice wouldn’t have worked, because this voice (heartless, exacting, frigid) was the one I was experiencing.

You and I are both dog lovers, but I couldn’t help but notice the hierarchy and ownership of animals. The dogs in North Dark serve a purpose as transportation. They are the sustainers of life but there is little affection for them. Can you talk a little about why you wrote the dogs with such distance?

I read a lot of Jack London. The Call of the Wild is far superior to White Fang, but both were major influences on North Dark. If North Dark were a longer, more sustained fantasy, then other characters would have had their own arcs that would be pursued in chapters similar to Two Crows’. At least one of them would have been from the point of view of a sled dog. I would have loved to have written that. However, this was meant to be a novella, delivered in a single concussive blow.

Two Crows’ mission and world view is single-minded. He has little time to consider anything outside of his mission. As such, dogs, people, everything are all secondary to his goal.

Perhaps it’s that concussive blow and the single-minded survival nature that makes the genre so urgent. As you know, I don’t read a lot of apocalyptic fiction, and I’m not the biggest fan of violence. But I loved this book. Two Crows’ journey is vicious and painful. Was the violence necessary to make him vulnerable?

Perhaps it’s that concussive blow and the single-minded survival nature that makes the genre so urgent. As you know, I don’t read a lot of apocalyptic fiction, and I’m not the biggest fan of violence. But I loved this book. Two Crows’ journey is vicious and painful. Was the violence necessary to make him vulnerable?

Yeah, I agree about the violence. When someone describes a current work (film, show, book, or whatever) to me as “violent,” I immediately feel a kind of sharp and adverse suspicion. It’s not because I think violence doesn’t belong in fiction; it’s because it’s so often gratuitous, complexly choreographed, and false. And I’ve never seen a real fight in my life that looked like an overly rehearsed dance. It’s always brief, concussive, and at least a little horrifying. It was clear to me, from the first scenes, that North Dark demanded physical stakes to match the emotional ones. It’s about characters losing their families, their sanity, and their limbs.

I believed, from the outset, that it was important this novella contain violence rather than action. Action is ballet. Violence is consequence. I wanted that idea to live in every physical interaction contained in this book.

Though he makes such a brief appearance on Two Crows’ quest, I found Burner a compelling character. Perhaps because he is the one person that we can connect with and understand; he lives in a house, craves connection, offers humanity. At this point in the story, neither man can speak. Their injuries are too great. Two Crows’ jaw is broken and he has fresh wounds. Burner is missing his tongue and all of his teeth and is covered in scars. Yet they communicate. What are you accomplishing by continually silencing Two Crows? Just when we want to hear his justifications most, his speech is taken?

A main character who can’t speak has to learn how to communicate in other ways: his eyes, his gestures, his actions. Two Crows writes, he speaks through proxies, he also uses what I wouldn’t call telepathy, but maybe the same kind of emotional telepathy we all use.

The character of Burner—a mute traveler he encounters on the dogsled trail—intrigued me because it’s the first time the field is leveled for Two Crows. He’s dealing with another who is, for the first time, his physical equal instead of his superior. Two Crows has a real opportunity to, essentially, make a friend. I didn’t know if he would. I wanted him to.

Then, Two Crows loses his sight in one eye? Then, he’s masked? You’re completely stripping your main character of his weapons and yet you send him continually into tougher battles to survive. Why?

Two Crows is not on what I would call “The Hero’s Journey.” His is much more the villain’s journey. As a consequence, he’s not continually collecting assistants, boons and glories. Instead, he’s losing. He’s losing his voice, his mind, his body parts. All the while he’s being reduced, Obsidian—this ghostlike doppelganger that follows him for much of the book—is increasing in size, stature, and influence. There’s a transference taking place. One that winds up having severe consequences, not only for Two Crows, but his remaining family, and other victims in this world.

Speaking of victims, you have to know I am going to call you on this: most of your female characters are dwarfs, hags, hunchbacks, or prostitutes. Come on, Lane. Justify yourself.

What’s wrong with dwarfs, hags, hunchbacks or prostitutes? Also, don’t forget the only selfless characters in the book: the team of female doctors and nurses traveling the world by boat to help the sick and afflicted. Also, there’s the beautiful woman, Doctor Bell, who goes to greater lengths than any other to end a pervasive and destructive plague. But I understand your point.

North Dark is a book populated almost entirely by grotesques, because the world in which it occurs is aggressively grotesque. Every other character, male or female, is missing just about half their body. And almost no one has anyone’s best interest in mind but their own. It’s an indiscriminate horror show of a world that Two Crows must plow through.

Let’s talk about Two Crows’ Obsidian. He seems to operate as an internal muse but also a guide and warning system. How do you think he helps Two Crows? What do we learn from him?

Obsidian is not clear cut. Is he a spirit? A projection? Is he real? At first it was not clear to me and it was also not clear to Two Crows.

It wasn’t clear to me either. I even stopped my reading to research the word. Technically, it’s a sharp, volcanic glass, but you’re using it as an idea, as a name?

Obsidian is one of the book’s central mysteries. His ultimate impact on Two Crows isn’t revealed until the end, but throughout the length of the novella he acts as guide, predator, counselor and demon. Whatever he is (he begins as a ghost-like wolf and eventually through the course of his transformation becomes a kind of volcanic half-giant) he is absolutely necessary to Two Crows. In times of extreme stress, people can envision or project dead family members or imaginary friends; what if one of those turned against you? Or was flatly evil from the get-go?

Obsidian is one of the book’s central mysteries. His ultimate impact on Two Crows isn’t revealed until the end, but throughout the length of the novella he acts as guide, predator, counselor and demon. Whatever he is (he begins as a ghost-like wolf and eventually through the course of his transformation becomes a kind of volcanic half-giant) he is absolutely necessary to Two Crows. In times of extreme stress, people can envision or project dead family members or imaginary friends; what if one of those turned against you? Or was flatly evil from the get-go?

It think it’s safe to say as your friend since graduate school, I’ve read almost everything you’ve ever written. Your first novel, which was one of my favorite reads, was essentially a coming of age young adult story. It was sensitive and raw. North Dark is a vastly different novella. How do you think your voice has changed over the years? What does this say about the evolution of a writer?

North Dark is two different things. On one level, it was a therapeutic exercise to get me through the prolonged death of my dog. On another level, it is a highly constructed art object. It was not at all me just ruminating about death, loss, and guilt. Instead, it was very much a considered, drafted, and detailed effort to produce the most satisfying and persuasive piece of fiction I was capable of.

I think there’s overwhelming value in deeply personal, cathartic, even self-indulgent work, but that’s not what North Dark is. I’m not as interested in me as I once was. In this writing, my concern was on this conflicted, complex character Two Crows, and the rough, broken world he inhabits.

What are you working on now?

Right now I’m currently shopping a novel. It’s a historical thriller about an American thief attempting to penetrate Communist China during the Cold War.

Your thief reminds me of where we started. Does revenge justify betrayal? In your definition of morality, is Two Crows redeemable?

A good friend of mine and I have a long running argument about whether or not people change. I believe we can and we do. I think I’ve changed. I also subscribe to the Ursula K. Le Guinn notion that change—not just conflict—is what drives fiction. If people or characters don’t change, then what are hoping for as humans or readers of story?

Change is integral to who we are. And I think as long as there exists the possibility of change, then there is always the chance of redemption. North Dark is a dark book—no question—but it’s not all doom and gloom. There is love throughout; love for my dog Charlie, love for the transformative nature of adventure, love for animals who defeat and defy silly devices like language, and always the love for something as powerful and inexplicable as story—probably the best and most basic way to process life. I hope that love is what drives and animates North Dark.