“Emerging” writers often search for clues and how-to’s, sometimes agonizing over what to do next with our lives and careers. We mine our own pasts, go to the local watering hole, coffee shops, or our private dens. Then we have more practical concerns: Should I apply for an MFA? What do I do after? Should I send my manuscript to an agent? A small publisher? Move to New York? Stay in the country? Teach? Scrap the whole project? Start over again? Two books that have shed light on the process of creativity of great artists both young and old are The Art of Youth: Crane, Carrington, Gershwin, and The Nature of First Acts (New Harvest) and Lastingness: The Art of Old Age (Grand Central), both by Nicholas Delbanco.

The Art of Youth carries the reader through intimate portrayals of artists who achieved heightened success early in life. Delbanco invites the reader to “imagine if the youthful dead could revisit their own past.” The book, written in Delbanco’s clean, honest prose style, combines thorough research with masterful essayistic turns. In Lastingness, Delbanco explores the qualities of great artists who, into their later years, sustained their art or pushed it forward.

Reading these books side by side, a broader sense of the mystery, and sometimes magic, of great art emerges. Lastingness and The Art of Youth are studies of virtuosi, and the reader takes away from them rare details of artist’s lives. Both allowed me to share some of my own grief with the sufferings and bittersweet redemptions shared by the gentle yet discerning voice of the author. And as odd as it may seem, when Delbanco writes that in some cases “Lady luck has much to do with this,” I found great consolation in giving in to some higher form of grace as a writer. What separates the haves from the have-nots? And what role has time played in our perceptions of them? Naturally I took to inviting the author, a former teacher of mine, to sit and chat with me. Mr. Delbanco and I corresponded while he was between his travels.

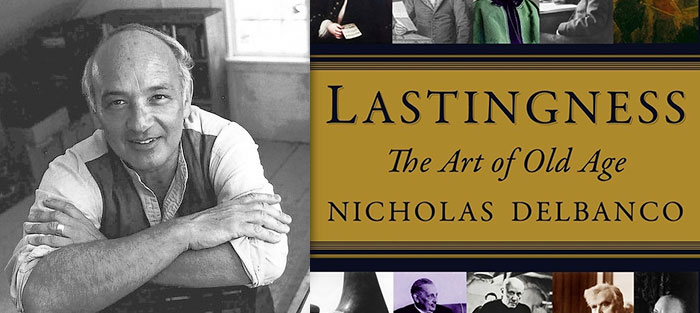

Nicholas Delbanco is the author of twenty-seven books of fiction and non-fiction. His most recent works in the latter genre are the subject of this interview; his most recent novels are The Count of Concord and Spring and Fall, and the reissued Sherbrookes trilogy. His awards include the J.S. Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship in Fiction and, twice, the National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in Fiction. Together with the late John Gardner, he was the founding Director of the Bennington Writing Workshops. He is the Robert Frost Distinguished University Professor of English Literature and the Director of the Hopwood Awards Program at the University of Michigan.

Interview:

When did you know that you wanted to be a writer?

As I write in The Art of Youth, words, for me, were magic all along. I cannot remember a time, in truth, when words were not my silent companions and some sort of patter was not in my head; the sound and look of English compelled me from the start. There are children who respond to melody or contour with a quickened pulse and full attention; my siren song was speech. And I was graduated from college with a book contract for my first novel, so I never really had to deal with that long slog of uncertainty; my own apprentice pages got published rather than shelved.

As a child, did you have any relatives or neighbors who were memorable storytellers?

As a child, did you have any relatives or neighbors who were memorable storytellers?

I had a goodly number of “characters” in my childhood, and some of them highly verbal, but there was no real tradition of story-telling in my family, and in any case the language I heard when an infant was German. But it’s possible—indeed, plausible—that to have been raised by folk whose principal interests were in the visual and musical arts (my mother was an avid reader but a student of philosophy rather more than literature), I was able to define myself, by contrast, as someone who expressed himself via the written word. And, yes, I do believe in the instruction as well as delight of nursery rhymes; those songs are with me still. Jack and Jill went up the hill…

In The Art of Youth you mention one of the measures of an artist is their sense of energy. Can you elaborate?

I tried to pick dissimilar figures in that book—not ones who present the same problem or have the same degree of attainment. Too, they work in different genres: Stephen Crane is a writer, Dora Carrington a painter, George Gershwin a musician. And their careers had different arcs, different degrees of success.

I think that each of them—and other figures I allude to glancingly—were energetic to a degree beyond that of normal men and women; their productivity was, no better word for it, prodigious.

Did you also find that environment played a significant role in either helping or hindering these various artists?

It depends what you mean by “environment.” Claude Monet went near-blind, Francisco Goya went almost totally deaf. This impacted their art in crucial and important ways, but most of the artists I profiled did their late work in relative comfort, having attained at least a degree of commercial success. Giuseppe de Lampedusa is an exception to this rule—but was, after all, a prince.

We are told tales warning against the impatience of youth – the myth of Icarus, for example – so why do so many of us still “put the cart before the horse” so to speak?

Young Icarus who flew too high—defying the instructions of that master maker, his father—is an emblem both of youthful aspiration and the risks attached. If we disobey our parents, we may first soar, then fall. The ‘old artificer’ Daedalus (so described by James Joyce in the last lines of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man) survived his son and, mourning him, became an example of the classical, not romantic, figure. He valued order, not disruption; he wanted to keep things intact. The senior’s style was that of power-in-reserve, the junior’s that of power-on-display. The first of these figures endorses restraint; the second embodies release.

Is there such a thing as a true prodigy?

Yes. And it doesn’t have to be an “artistic” prodigy; many of our most notable mathematicians and physicists, for example, declare themselves when young.

You say, in Lastingness, that a “genius” dead before his or her time is a romantic construct.

In the technical sense, there’s no such thing as “before his or her time.” We die when we die. Finita la musica. Punkt.

Are there any glaring differences, in your view, between writers today and those of past generations?

I’m not the best judge of this—can’t distinguish, truly, between the forest and trees. It’s obvious that technology has altered how we address the page, obvious also that our “opportunities” are other than those that thirty or fifty years ago obtained. When I was in college, my cadre wanted to be poets and prose fiction writers and, occasionally, a playwright; now the majority of those who love language dream of screenplays and television scripts. The locus of aspiration and the tools may have changed; the desire to inhabit a world of words remains, I think, the same.

What are some of the risks for a writer whose work has been rewarded or celebrated in a particular way?

You’re asking here, I think, about the deep paralysis of repetition. If you’ve been rewarded for and accomplished at a certain kind of writing, it’s hard to begin afresh; formula writers don’t try to; indeed, it would shock their readership if the terms of engagement were changed. But many more serious artists play less to their weakness than strength, and sometimes this too can become formulaic: Think of the late Hemingway or Faulkner and the risks of repetition should come clear. The rhythms of the prose are constant, the syntax and character constructs and thematic concerns stay the same. But it’s all habitual, a kind of shadowboxing enacted in slow motion; there’s no creative challenge while they practice their old moves.

What books or authors, if any, do you still go back to again and again with a sense of awe and wonder?

What books or authors, if any, do you still go back to again and again with a sense of awe and wonder?

One of the pleasures of teaching is that we get to re-read texts, to study twice and ten times what we construe to be excellent work. Indeed, my definition of a masterpiece is something that improves upon rereading. So, to answer your question, I “go back again and again with a sense of awe and wonder” now to books I’ll teach once more this fall—novels by Faulkner, Fitzgerald, Ford, Hawthorne, Hemingway, Joyce, Lowry, Woolf et. al. I’ve also been rereading those novels I admired when young (Dickens’s Nicholas Nickleby, Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss, Mann’s Buddenbrooks, etc.) And there’s always William Shakespeare, inexhaustible.

So what, then, are some significant differences between “lasting” works of art and works that fade?

Some of this, of course, has to do with critical and collective reception over time. But some of it has also to do with what we might as well call the “eternal verities”—as opposed to issues and temporary behavior-patterns that can fade or change. The former lasts; the latter disappears.

In Lastingness, you mention such female artists as Georgia O’Keeffe, Clara Schumann, Georges Sand. However, most artists who prevail over time are predominantly male. Did you find any major clues as to why this is so?

That book dealt with the great dead, and it’s the simple statistical case so that it read that a career in art was largely and only available to men; look at Virginia Woolf’s splendid disquisition on the fate of “Shakespeare’s sister.” The chance to make a life (not to mention a living) as artist was a chance that few women could take. More likely there’d be drudgery, small formal education or opportunity for self-expression, the dangers of childbearing and bodily assault. In the twentieth century, things began to change—and in our present moment there are female practitioners everywhere in art.

In class, you invited our group to bring in samples of writing by published authors that we both liked and disliked. What are some useful things that a writer can learn from reading books that they dislike?

I wrote a textbook called The Sincerest Form: Writing Fiction by Imitation whose central premise was and is that we learn by emulation. Imitation. Flattery. The desire to perform those tricks that dazzle us when others pull them off. And it’s of course useful as well to know what not to do.

Where would you say that the line is drawn between precociousness and true talent?

All of us are promising; many are precocious. Some become distinguished. The trick is to negotiate the forty or fifty years of hard work in between.

In what ways can artists avoid squandering their gifts?

There’s a wonderful book called Enemies of Promise by Cyril Connolly that I commend to all your readers; as its title suggests, it’s a catalogue of obstacles the artist must attempt to overcome. As a record of the risks that any gifted child confronts when trying to “deliver” on promise, it stays germane, though the terms of the problem have changed.

You are quite a prolific writer: what drives you?

I’ve written often about the “benefits” of regularity—so much so that I sometimes feel like your neighborhood druggist extolling the virtues of habit. Like any other habitual practice, this one would be harder to break than it once was to make. I started writing early in my lifetime and start early in the day; I’ve done it now not merely for years and decades but centuries, millennia. And see no reason to stop.

Of all the artists you examined in your last two books, Lastingness and The Art of Youth, with whom did you connect personally?

I’d like to claim a personal connection to them all. Indeed, I only researched and then wrote about those artists for whom I felt, as it were, an elective affinity; there were no “hatchet jobs.” But it’s safe to say I learned the most about those artists of whom I’d known, beforehand, the least—so that, in the study of old age, the work of Giuseppe de Lampedusa and, in the study of youth, the work of Dora Carrington gave me keen-edged pleasure: a writer and a painter whose efforts moved me much.