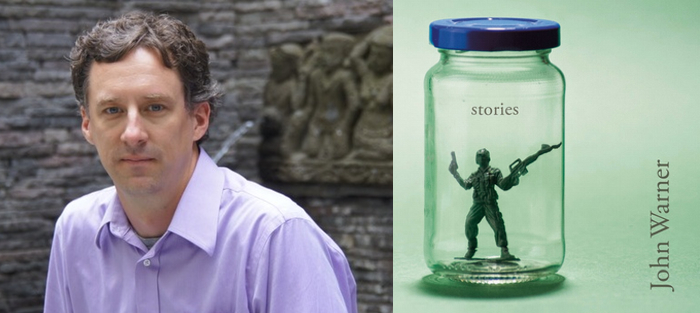

John Warner will still occasionally bring up, ruefully, the sting of receiving a B from me in his first creative writing class, back in the early 90s. I don’t know what I was thinking! I always hasten to remind him that I did give him an A in the second class he took with me. Thank goodness—that A gives me some credibility to claim that I could see the beginnings of John’s unusual and adventurous career as a writer, editor, and literary innovator on the web.

His first publications were books of humor, My First Presidentiary (2001), an inside look at George W. Bush’s crayon-drawn scrapbook, and Fondling Your Muse (2005), a wickedly funny send-up of literary craft books. At the same time John was creating a name for himself as the editor of McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, and the co-founder of (and regular commentator for) The Morning News’ Tournament of Books, an annual and wildly popular sixteen-bracket book competition. He also invented a kind of alter ego for himself: the Biblioracle, possessed of seemingly mystical book recommendation powers. John has recently added to his long list of web accomplishments a column, “Just Visiting,” that he writes for Inside Higher Ed about his experiences as a non-tenure track university professor. He teaches at the College of Charleston.

In 2011 Soho Press published his novel The Funny Man, the unsettling tale of a stand-up comedian whose fame rests on his ability to fit his entire fist in his mouth (John is now working on the screenplay for the movie version). His latest work of fiction is Tough Day for the Army, just out from Louisiana State University Press, a collection of structurally sophisticated and deeply felt short stories that balance empathy and humor with a clear-eyed look at our human foibles. It’s already creating a buzz, with a number of terrific initial reviews, including a starred review in Publisher’s Weekly:

Warner has produced a short story collection that mashes the surreal with the heartfelt to fantastic effect . . . Like George Saunders and Etgar Keret, Warner plays with conventional mores, turning them on their ear. Also like those authors, Warner successfully layers his satire with rich characters and a general playfulness with form that somehow renders a deep emotional resonance. The result is a well-written and wonderfully comedic collection of short stories that gooses as much as it gives.

This interviewed was conducted in two parts. In the first, we discussed John Warner’s story collection, Tough Day for the Army, and in the second his career as a kind of Internet literary impresario.

Interview:

Philip Graham: The title story of your collection, Tough Day for the Army, is set in a generic waiting room. An entire army waits for orders, uncomfortably filling out what seems to be a job form, and scouting the stacks of old magazines on the end tables. As with most of your stories, a certain amount of pleasurable adjustment is needed to dig into the world you’re assembling, and a sentence really jumped out at me: “The idea is that one thing becomes another; then it’s not lying.” Care to elaborate?

John Warner: In the story, the line is in the mouth of a woman waiting nearby the army, warning them from thinking that the pictures of food in the magazines that look so appetizing are representative of the actual food. To me, it speaks to our collective willingness to believe in things we know are fake, like the photo-shopped images of women in magazines, which create anatomical impossibilities, and yet become genuine symbols of desire. Or in the military vein, a president hanging a “Mission Accomplished” banner across an aircraft carrier serves as a substitute for actually, you know, having accomplished the mission. (Whatever the mission might have been.) I feel like “we” (me definitely included) are hardwired for this kind of gullibility, and the tension between these fantasies and our realities has always been interesting to me.

In a sense, that sentence seems to be a guiding light for many of the other stories in your collection, of one thing becoming another.

There’s such a pleasurable tension in many of the stories, and after a while the reader waits to see how the one thing she is reading about will turn out to also be something else. For example, “Corrections and Clarifications” seems to promise a newspaper’s dry account of minor errors in a previous edition, and the first paragraph or so seems to bear this out, but soon a hidden narrative begins to surface, and the reader is happily reading between the lines and filling in the unspoken.

That story and some others written in unconventional forms are examples of what George Saunders refers to as “finding strategies to coping with your weaknesses.” I revered writers like Carver, Beattie, Bobbie Ann Mason, but I couldn’t manage to create even satisfactory (let alone good) stories like theirs. When Carver’s characters sit across the table from each other and talk, it’s riveting and alive. Mine just stared at each other like a couple of dum-dums doing imitations of Raymond Carver characters.

So I had to go looking for other ways inside situations and, most of all, to create interesting tension. It’s the same feeling as Carver, et al.—things are not as they seem—but coming at it from a different angle.

Well, you’re being a bit too modest here, I think. “Nelson vs. the Mormon Smile” is a straightforward story that surprises and becomes deeply moving by the end. Poor, hapless Nelson’s crush on Chelsea Stubbins, a squeaky-blonde icon of Mormon beauty, seems doomed from the start. I found myself rooting against his adolescent foolish self, but the party scene upended all my expectations, and the conversation between Chelsea and a hashed-out Nelson is so tender and sad, and you maintain a delicate, moving balance of surprise throughout their encounter. The final story in the collection, “A Love Story,” has this sort of power too. Not to knock your stories that play so well with form.

Well, you’re being a bit too modest here, I think. “Nelson vs. the Mormon Smile” is a straightforward story that surprises and becomes deeply moving by the end. Poor, hapless Nelson’s crush on Chelsea Stubbins, a squeaky-blonde icon of Mormon beauty, seems doomed from the start. I found myself rooting against his adolescent foolish self, but the party scene upended all my expectations, and the conversation between Chelsea and a hashed-out Nelson is so tender and sad, and you maintain a delicate, moving balance of surprise throughout their encounter. The final story in the collection, “A Love Story,” has this sort of power too. Not to knock your stories that play so well with form.

I think it’s probably not coincidental that “Nelson…” and “A Love Story” are two much more recent stories than the others, and were born out of a desire to give another shot at writing the kinds of stories that first made me want to write. Most of what I seem to gravitate towards these days is more like this, not that I’ve abandoned other experiments. More than anything, I like to keep myself interested in the work. Forcing myself into a different form sometimes opens things up.

I agree—one of my favorite short stories is “Acknowledgments,” by Paul Theroux. It’s in the form of the acknowledgements at the back of a scholarly book about a (very) minor English poet, but soon enough a buried tale of sex, murder, bribery, and ambition rises through the bland prose.

Restraint seems to be a guiding force in these types of stories. In “What I Am, What I Found, What I Did (Attachments Enclosed),” the earnest narrator refers to 819 supporting attachments, which never appear in the story itself, nor do they need to.

The direct inspiration there was Infinite Jest (Little, Brown and Company, 1996), which I was reading during the end of my graduate school studies, which is when I wrote the initial draft of “What I Am…” IJ famously has all those endnotes, but the endnotes refer to hundreds and thousands of artifacts (like the Infinite Jest film itself) that exist in the universe of the novel and are an influence in that world, even though the reader will never see or experience them directly.

Sometimes your documents do appear, as in the story with perhaps the world record-long title, “Return-to-Sensibility Problems after Penetrating Captive Bolt Stunning of Cattle in Commercial Beef Slaughter Plant #5867: Confidential Report.” That’s two-tweet territory.

So this story is based on a real-life document of almost the same title, a published study by the prominent and famous veterinary researcher Temple Grandin (subject of an HBO biopic in which she was played by Claire Danes). The original study is pretty much what the story suggests: Grandin was hired to inspect slaughterhouses that had difficulties in properly stunning cattle. As she writes in her memoirs, and as she’s portrayed in the movie, she has a gift of empathy with livestock, capable of seeing the experience of being led to slaughter through their eyes. She isn’t an animal rights activist, but does believe that as long as we’re going to eat meat, the way we kill it should be as peaceful and humane as possible. I ran across the article in the Journal of the Veterinary Medical Association (my wife being a veterinarian) and was struck by the dispassionate language used to describe what must be unbelievable carnage. The actions described in the story, like hanging a not-all-the-way dead bull on a “bleed rail” and slitting its throat, seemed to happen pretty often, at least according to the report.

I changed the perspective around, so these things were seen by someone not so immune or dispassionate, but kept the report format and saw it gave me an interesting tension, a story that was struggling to break free of the form.

What I’m personally proud of is that we learn very little about the narrator, and yet I think it becomes clear that this experience in the slaughterhouse has been transformative. Everything is told by inference and implication.

Yes, and the poor guy is falling apart during those weeks of his inspection. Grandin has autism, and so that emotional reserve is understandable, as well as her empathy (she believes that autistic people and animals sometimes see the world in similar ways). But the hero of your story is an ordinary slub, like you or I, and so is affected by all the organized carnage. At the same time, he seems to develop a respect for the foreman, a man who is doing a dirty job the best he can. That’s what I love about the story, and all your stories, in general—there are no easy answers, and your characters often reveal a hidden facet that gives them an extra graceful breath.

Shucks. I’m blushing. One of the personal, fundamental tensions in my work is that deep down (or not even all that deep down), I see mankind basically as a pestilence, bent on destroying each other and the Earth itself. This cannot really be stopped. We are just absolutely terrible. There really isn’t much difference between us and the flesh-eating walkers of The Walking Dead. We just don’t moan quite as audibly.

And yet, sometimes we can break free of our monstrousness and be genuinely good and kind. I tend to give most every character that shows up in my stories the benefit of the doubt that they’re mostly in search of a good life that makes sense to them. That slaughterhouse foreman doesn’t like his job—because who would really enjoy being subject to carnage every last day—but there’s a dignity in doing it as it should be done.

One of the most powerful stories in the collection is “Not Schmitty,” which is about frat boys and a waterboarding hazing gone wrong and Schmitty becoming Not Schmitty, and a lifetime haunting. And told very effectively in the first-person plural. Please tell me that this isn’t also based on a true story.

Well…no. Except that I was in a fraternity in college, serving as president my senior year, in fact, and while we never did anything close to that extreme, or really anything even close to the stories you sometimes hear about fraternities (i.e., I was never in danger of physical harm, nor ever put anyone else in danger of physical harm), the mentality and groupthink is familiar to me, which is where the first-person plural perspective came from. The idea of waterboarding pledges does originate from an actual rumor on campus where I teach. I think it’s probably apocryphal, the same way there was a rumor when I was at Illinois that there was a fraternity where pledges had to raise a puppy and then strangle (or maybe drown) it prior to their initiation in order to show their dedication to the house.

My fraternity was very low key, relatively speaking, but the really interesting part to me has always been that all that male posturing and performance of machismo is rooted in vulnerability and insecurity. When the brothers waterboard Schmitty, they find this out for themselves.

Yes, and that comes across in large and small ways. I love the line in the story, “We know we are in love because when we say disgusting things about our girlfriends to our brothers, we feel regret.” How isolated they are, from their brothers, their girlfriends! And it’s related so matter-of-factly, as if an interior abyss hasn’t been revealed.

Admitting that you have made yourself vulnerable enough to fall in love with someone just doesn’t fly in the culture of the story. You can be interested in a relationship because someone is “hot,” but not if they make you feel your feelings. The irony of all of it is that a huge number of my fraternity brothers married women they met and started dating in college. And of that group, ninety-nine percent of them are still married, twenty plus years later. My fraternity was on the intellectual side, so we didn’t have much free-floating misogyny, but neither was there a lot of straight or frank talk about what was actually happening, which was the finding of a soul mate. It just wasn’t the kind of thing you’d be able to admit publicly, or maybe even to oneself. We were probably the poorer for it.

Ah, this reminds me of the last story in the book, “A Love Story.” The narrator, Josh, has been happily married a long time, and he and his wife have just recently decided not to bring children into a world as disturbing as the one in which we all find ourselves. This decision, however, in Josh’s words, “seals our fates only to each other,” and this is when his wife Beth begins asking him a simple question, “Do you love me?” His well-meaning and earnest answers, however, do not, in her opinion, pass some smell test.

I might as well just go ahead and admit that this is the most autobiographical story I’ve ever written, though it’s much more like “based on a true story” than having a serious fidelity to real life. Like adult Josh, when I jog I catalog my aches and pains and I had an unrequited crush in high school, but there’s lots of invention.

I might as well just go ahead and admit that this is the most autobiographical story I’ve ever written, though it’s much more like “based on a true story” than having a serious fidelity to real life. Like adult Josh, when I jog I catalog my aches and pains and I had an unrequited crush in high school, but there’s lots of invention.

The truest part of the story is the decision not to have children and the fact of how vulnerable this leaves us as we age. This isn’t to say that the reason to have children is so you have someone to look after you in your dotage, but one of the real benefits of children is that you hopefully have someone to look after you in your old age and not just look after you, but love you. Though, having children opens parents up to a different kind of vulnerability, the potential to lose a child, which would be catastrophic, the kind of thing that I can’t imagine recovering from. In a way, we’ve chosen a lesser vulnerability to a greater one. I can’t imagine ever definitively calling it the right choice, but it’s the one we’ve made.

When asked by his wife if he loves her, Josh says, “Of course,” as though it goes without saying, though “of course” it doesn’t go without saying. The problem is he doesn’t really know how to say it. The words are inevitably unsatisfactory, so it can only be done with deeds. But they’re deeds that need repetition and reinforcement, not a pro forma ritual, but a mindful practice. That’s a hard thing to do because one of the great things about someone loving you is that you can relax into the feeling. The difficulty is that there’s a short bridge from there to complacency.

It’s such a heartfelt story, with a teen-age crush contrasted with the labyrinths of adult love, and there’s the specter of mortality, that I’m not sure you could have gotten away with it as a lead-off in the collection. But you more than earn your stripes with a reader by the time it appears. And at the same time, after such a satisfying collection of emotionally and technically varied stories, there’s the sneaking suspicion that all might not be what it seems. As I mentioned at the beginning of the interview, I like that line from the title story, “The idea is that one thing becomes another; then it’s not lying.” And what we discover is that all the stories we’ve read are a kind of answer to Beth’s question, “Do you love me?” Nicely done.

Even in my most “realistic” story, I couldn’t resist a little metafictional twist. I think it’s partly a message to myself. As you well know, spending time writing short stories is a pretty irrational thing to do. The ones in the book span seventeen years in the making and represent another fifty or so that didn’t make the cut. What reason is there to persist, other than love?