Stephanie Jimenez’s debut novel, They Could Have Named Her Anything (Little A), revolves around two teenagers with roots in very different worlds, Maria and Rocky, who develop an intense and intricate friendship at their private high school. Told in alternating points of view between the two girls and their fathers, Miguel and Charlie, the novel interrogates subjects that are often taboo in books about young women: sex, but also class and money and the confines of masculinity.

I first encountered this novel when Stephanie’s editor, Vivian Lee, sent me an early copy to read. She thought, rightly so, that the overlap in our work meant it would appeal to me, and it did. The utter seriousness with which Jimenez examines girls’ lives caught my attention immediately, but I was also taken in by the craft of this book, with its delicate balance of point of view between the daughters and the fathers, and how it maintains nuance and complexity for every character and their varying desires. It’s a searing look at the real lives of young girls but also young men and adults—at the messes they make and the ones they clean up, at how they love one another and sometimes fail at it, too.

I wanted to talk to Stephanie more about her choices during writing this book, about how she made the characters’ humanity so palpable on every page. This summer we conducted this interview over text. I’d leave a question for Stephanie and she’d respond during the day. Coming back to the answers she’d left for me was such a pleasure.

Interview:

Danielle Lazarin: How did you decide to write a multi-perspective novel? Were all the voices there from early seeds? I’m particularly interested in how you decided to include the voices of the fathers for a novel that is so much about girlhood.

Stephanie Jimenez: This question makes me think that you already know that the first draft of this book did not include the perspective of the fathers. (Is it obvious?) My agent suggested to include an adult perspective, in part, because she believed that an adult perspective would ensure that the book would be read by adults. Hopefully, the perspectives of the fathers adds something meaningful to the book and isn’t just a trick to draw readers. This book is about girlhood, like you said, but it’s also about how adults interact with girlhood, if they do.

I didn’t know that! The fathers’ perspectives seem essential to me for exactly your note that the book is “about how adults interact with girlhood, if they do.” In fact, the confidence of the men in this book is striking, even as they’re often wrong about the girls and women they’re tied to. Do you think that the overconfidence of the male characters is restrictive for them while the girls, because they have more self-doubt and take bigger risks, might learn more?

Men always seem to know exactly how to do things, and I guess it’s because society’s rules generally work to their advantage, making them easy to follow. But in my mind, an inevitable part of being a girl is about dodging the horrible things that threaten to derail your life. After a childhood spent in a constant state of deflecting that which brings you harm while simultaneously searching for what brings you greater freedom, maybe women become more better adept at navigating crises.

Yes! It felt to me that, for example, when Charlie feels lost in the book he is truly lost, and when Maria or Rocky feel lost they’re more comfortable in that feeling and it allows for growth. But maybe that’s the difference between youth and age, and freedom and responsibility.

I also think it’s a juxtaposition between the worlds of men and women. Men are taught to be confident and assured, knowing that the world is fitted to their needs and desires, but women’s desire is constantly suppressed as they are subject to rules about where they can go, what they can wear, how and with whom they comport themselves. This is especially true in childhood and adolescence, which we know is the most formative time of a person’s social and emotional development. Jamaica Kincaid’s short story “Girl” comes to mind: “you are not a boy, you know,” which is a lesson Maria is constantly reminded of in her own conservative home. But perhaps being raised with the knowledge that she’s not a boy leads not just to resilience, but to the development of creativity. The experience of girlhood, even with all its perils, anxieties, and doubt, seems to make Maria and Rocky more creative and more willing to take risks in their friendships and lives in pursuit of that which will be most fulfilling.

The book has so many borders in it, but the way the characters move between them is so nuanced. Maria has access to lots of spaces but the more she moves between them, the less definitive her sense of belonging becomes. How did you approach the task of making the girls’ navigation of these spaces read as borders but not dichotomies?

New York City is among the most segregated cities in America. If Maria gets to navigate seamlessly through the many borders that divide the city, it’s because she is in a very unique position. I think you’re right to point out that Maria’s sense of belonging deteriorates as she moves through these spaces even as she seems to adapt to them seamlessly. Embedded in Maria’s struggle to understand herself is her struggle to understand the idea of meritocracy. Everyone is telling her she deserves the experience of an elite education, but why doesn’t that experience extend to her family or her friends? Why does she have to experience it alone? I think that’s what makes her friendship with Rocky so painful. Rocky genuinely wants to be a friend to Maria, but Rocky can’t really give her the answer to those questions, at least not one that’s satisfying to Maria. It’s this tension that starts to drive them apart.

I’m glad you mentioned this tension between the girls, as it’s a driving force from the first page to the last. Maria and Rocky find a companionship in one another that goes beyond a mutual desire for some aspects of the other’s life. How did this dynamic between them evolve as you wrote the book?

Early on in writing this book, I was searching for a concrete reason that could explain why their friendship wouldn’t be successful. But the reality is that often times we don’t know why our friendships end. One of the reasons I decided to write about teens is because, to some extent, their naivety brings them together. When Maria and Rocky become friends, they expect a ludicrous degree of fealty at all costs, so much so that they expect any transgression they commit against each other will be forgiven. They are friends and yet they have no concept of what it actually means to be a friend.

I also wanted to get at something else about female friendship, especially those early, intense ones, and it’s what you alluded to earlier about borders. Rocky and Maria are willing to cross borders to understand each other. They are more eager to see and look around each other’s lives. When Maria is invited to Rocky’s apartment, she knows she’s been given something intimate and special, and it has nothing to do with money, and everything to do with being brought into someone’s home. That sort of friendship is a gift. I don’t know if friends allow each other as much intimacy in adulthood.

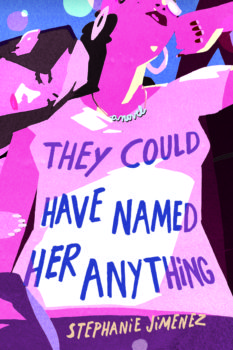

Switching gears some, can you talk about this larger-than-life cover? The nameplate necklace “a novel” killed me; it’s so New York and this version seemed the true root of how it was worn, unironically. Likewise, there’s an intimacy to the image of the girls, and yet a kind of anonymity. Did you have a lot of input on the design?

I love the cover. We commissioned an artist named Ron Wimberly, an NYC-based artist whose work is astounding. I remember seeing the initial sketch and seeing Rocky leaning on Maria and Maria turning to the window and knowing how gorgeously this captured their dynamic. And that vivid pink. One of the first things Maria notices about the girls at her private school is that even their color palette is different from hers—they’re always in pastel colors, creamy beiges and ballerina pinks. It feels like the best kind of indulgence to have such bold colors on the cover. My only real input was that I wanted the image to be abstract, so that you couldn’t immediately make out any key features about Rocky or Maria, which aligns with the title of the book. Obviously, it’s a book about race and class difference, but I also wanted to play with the idea of how those concepts can sometimes mean a little and sometimes mean a lot and how we can enlarge or make them smaller in our minds. I like that the visual differences between the girls are in those little, subtle details, like that unironic nameplate.

I love the cover. We commissioned an artist named Ron Wimberly, an NYC-based artist whose work is astounding. I remember seeing the initial sketch and seeing Rocky leaning on Maria and Maria turning to the window and knowing how gorgeously this captured their dynamic. And that vivid pink. One of the first things Maria notices about the girls at her private school is that even their color palette is different from hers—they’re always in pastel colors, creamy beiges and ballerina pinks. It feels like the best kind of indulgence to have such bold colors on the cover. My only real input was that I wanted the image to be abstract, so that you couldn’t immediately make out any key features about Rocky or Maria, which aligns with the title of the book. Obviously, it’s a book about race and class difference, but I also wanted to play with the idea of how those concepts can sometimes mean a little and sometimes mean a lot and how we can enlarge or make them smaller in our minds. I like that the visual differences between the girls are in those little, subtle details, like that unironic nameplate.

As a native outer-borough New Yorker, I really loved how you cut Maria’s enchantment with the glitzier versions of New York with her genuine love for Queens:

Emerson said that you could find infinite beauty in nature, but Maria knew you could do the same thing in the city, only that nobody really knew how. Nobody knew how to look at Queens Boulevard like she did, and it was special that she’d been able to develop this taste.

What draws you as a writer to talking about Queens and the urban landscape in this way?

New York is obviously interesting, but Queens is such a fascinating place because it’s a hodge-podge of everything. I remember when that Con Ed explosion happened and we all thought a UFO landed, someone on Twitter was like “is anyone surprised the aliens chose Astoria for their landing?” Queens is treated like a little-known planet—far away and a last resort for habitation. I like that the rest of the city can’t seem to pin us down.

As for the urban landscape, there’s this concept that urban childhoods are less beautiful than suburban ones. And though it’s true that a city upbringing is not a sheltered one, the suggestion that there is somehow less beauty in urban childhoods is ridiculous. So, Maria takes this classic text and Emerson’s notion of the sublime and easily locates it in her own life. She experiences the sublime when she steps out at two in the morning and gasps, realizing she’s never seen Queens Boulevard entirely empty before.

My friends and I are guilty of grumbling about the city’s bad air quality and too many people. But Maria’s capacity for wonder and awe is heightened in part because she is, in many ways, still only a child. She is able to truly see how often the city is astonishing.

You’ve been sharing your journey as a debut writer on the website Debutante Ball. What have been some of the key experiences for you as a debut novelist?

The Debutante Ball is a collective blog where five debut women authors blog about their process of publishing their first books. It was founded in 2007, and every year a new group of writers is selected to run the blog. I agreed to be a part of it because I thought it would be helpful for me to write about things like querying, signing a book contract, and finding comp titles—those things that can feel seem very mysterious to emerging writers.

One of the earliest joys in the publishing process was seeing my book included in R.O. Kwon’s list of 2019 books by women and non-binary individuals of color on Electric Literature. It was the first publicity hit for the novel, and it was also the first day of 2019. It reminded me of the generosity of other authors and writers, and how willing we are to support one another. Being a writer has brought a lot of wonderful people into my life that I would have otherwise never known. It has also really expanded my reading. I suddenly have galleys from other debut authors in genres I would not have considered otherwise. Authors put so much pressure on themselves, and when you’re reading the work of so many other self-doubting authors, finding something you love in each of their books, it humbles you a little. I think it helps in this process to take yourself and your own writing less seriously.

Sometimes we’re set up to be unnecessarily and detrimentally competitive rather than to work on the generosity toward other writers you speak of. But what good is being on a shelf by ourselves? So many of us begin as writers because we are thrilled by other writers and the way their stories have dug into our being. What formed you as a writer?

I think the earliest memory I have of really being in awe of books was as a ten-year-old reading Richard Wright’s memoir. It was part of the curriculum for this program I was enrolled in called Prep for Prep and they made us read all sorts of books that are not generally thought to be at a fifth grader’s reading level: Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun, Richard Wright’s Black Boy, Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, Sandra Cisneros’ The House on Mango Street. I was ten or eleven years old and I can hardly remember what I thought about on a day-to-day basis, but I remember reading those books. I am lucky to have been exposed to that sort of material so young and I’m realizing right now that my introduction to literature was almost exclusively writers of color. That’s pretty amazing. It also makes me sad because for most of my life, I’ve felt like I’m not very well read compared to my literary peers, all of whom seem to know more about Russian and German literature than I do. Overall, I’m not really the kind of reader who picks up a book based on who wrote it. I love Sandra Cisneros, but I also read Wuthering Heights in high school and wept. I think that remains the problem with how we market literature. We often think about books in terms of their audience, and that the identity of the writer matches the identity of the reader, but of course, that’s not always the case.

I think the earliest memory I have of really being in awe of books was as a ten-year-old reading Richard Wright’s memoir. It was part of the curriculum for this program I was enrolled in called Prep for Prep and they made us read all sorts of books that are not generally thought to be at a fifth grader’s reading level: Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun, Richard Wright’s Black Boy, Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, Sandra Cisneros’ The House on Mango Street. I was ten or eleven years old and I can hardly remember what I thought about on a day-to-day basis, but I remember reading those books. I am lucky to have been exposed to that sort of material so young and I’m realizing right now that my introduction to literature was almost exclusively writers of color. That’s pretty amazing. It also makes me sad because for most of my life, I’ve felt like I’m not very well read compared to my literary peers, all of whom seem to know more about Russian and German literature than I do. Overall, I’m not really the kind of reader who picks up a book based on who wrote it. I love Sandra Cisneros, but I also read Wuthering Heights in high school and wept. I think that remains the problem with how we market literature. We often think about books in terms of their audience, and that the identity of the writer matches the identity of the reader, but of course, that’s not always the case.

Speaking of education, it struck me that this book is about how the entry to all these “desirable” places doesn’t necessarily backfire for Maria, but it affords her an expansive education in the task of navigating class and race and privilege lines in her own future; she learns so much about what it all costs, and how that cost differs from that to her parents. Where is the space where you feel you’ve been most educated in your life?

I went to college in California, and it was the first time I met Mexican Americans who called themselves Chicano. I had no idea what that term referred to. I learned that it was steeped in the activist tradition of the ’60s, specifically the civil rights movement in Los Angeles. Meanwhile, the Latinos I knew in New York were calling themselves by words that emphasized their connection to Europeans, like when they referred to themselves as “Spanish.” I remember knowing how powerful the term Chicano was because it was borne of the struggle of Mexicans in America to be recognized and treated with dignity. I’m Costa Rican-Colombian-American. And to constantly try to explain yourself with a hyphen, with saying you’re a little bit of this and a little bit of that, is tiresome and disorienting. I loved the idea of not being a liminal person with a liminal identity. In California, I felt like I met people who knew the story of who they were. That capacity for self-knowledge was a model and inspiration for me.