When I decided that I wanted to read more mass-market suspense and crime novels this year, I took it for granted that some of them would be bad. I was reading for plot, I reasoned. I couldn’t also expect richly complex characters, beautiful language, sharp dialogue—certainly not in every case. My prediction proved correct: some of the books I picked up were bad, and some were really bad. A few seemed as if they could have been written by a computer that had been tasked with combining aspects of Gillian Flynn and Paula Hawkins novels, drafted in prose that could be comprehended by an eight-year-old. Either I was a snob (entirely possible), or a lot of these writers cared less about quality than in following a formula.

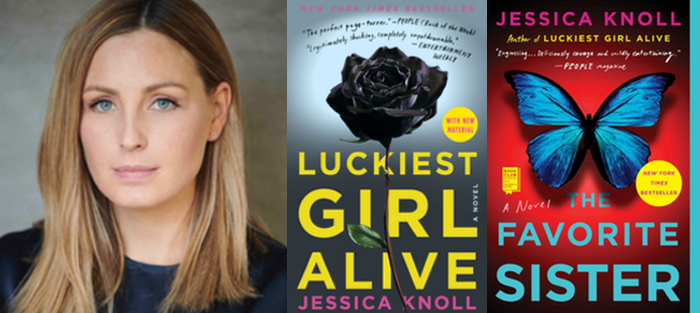

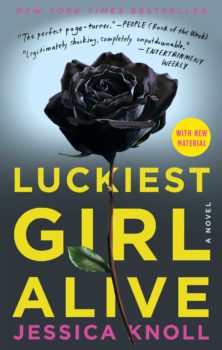

Then I found Jessica Knoll. The fact that I hadn’t heard of her before said less about her visibility than my ignorance: her debut, The Luckiest Girl Alive (2015), had been an instant New York Times bestseller, sold in thirty-eight countries, and was later optioned by Reese Witherspoon. All I knew was that it looked like a fun read, a good way to while away a weekend. By the end of the first chapter, I found myself reaching for my pen, underlining descriptions and bits of dialogue. The novel delivered all the suspense and tension I expected, but it also satisfied the other part of my brain, the part that wanted realistic, complex characters and great sentences.

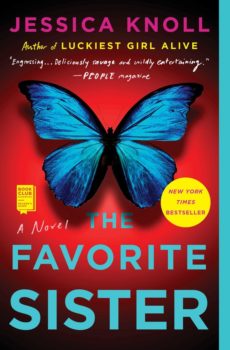

I tore through Luckiest Girl and went on to Knoll’s second novel, The Favorite Sister, out in paperback this month. The Favorite Sister follows five women behind the scenes of a reality show that’s been created to transcend the trashy associations of the genre (the cast members are entrepreneurs, not housewives, and they’re supposed to help and support each other) but inevitably, as the hunt for ratings trumps principle, drama ensues. On the way, Knoll examines female friendship, the role of women as producers and consumers, and the divide between art and entertainment. The novel has big themes to tackle, but it does it in a way that’s so subtle and so entertaining that it may take you a while to notice.

I had also started following Knoll on social media, and I loved how honest and outspoken she was about her experience in publishing, and perhaps most notably, the money she’s made. She’s just as funny and straightforward speaking as herself as she is in her fiction.

Interview:

Polly Atwell: You said in your New York Times editorial that you’d spent months researching the publishing industry before writing The Luckiest Girl Alive. What did that entail?

Jessica Knoll: At the time, I was an editorial assistant at Cosmo. I was assisting John Searles, who was a crime writer, so I learned a lot from him about authors I should be reading. I learned about Publishers Weekly—I was twenty-three, I didn’t even know what that was. I didn’t know about any of the dailies in the publishing industry, but then I was checking it every day. I was able to keep up with what books were hot in the marketplace. Then I started to learn the terminology, and when an author did get an exciting book deal, I could then research that author. I Googled them to see who they were, what was their background, what kind of platform did they have to offer. I do think that helped when my own book went out on the market.

Clearly you make smart marketing decisions. But some books that are written for the market are also terrible, while your novels are so well-crafted. How do you think about balancing that natural desire to write the best book you can with the desire to write a book that will sell?

At the time I worked at Cosmo—this was around 2008, 2009—nonfiction relationship guides and romance were big sellers. A lot of people said to me, as a Cosmo editor, that that would be a natural next step for me. They said that my day job would lend itself very well to that kind of book, but that just didn’t resonate with me. I thought, “I don’t think I could tell a story that way, and I don’t want to.”

When you say, “I’m writing for the marketplace,” it can sound really calculating, for one thing, but it’s also not going to lead to a very good book. At that time, I was waiting for inspiration—something I would read that would make me think, “Oh, that’s the type of book I want to write, that’s the voice that sounds right to me.” I’ve said this so many times that I think Gillian Flynn might take out a restraining order on me, but for me that book was Dark Places. A galley landed on my desk on a Friday afternoon, and I took it home with me and tore through it over the weekend. And that to me was the first time that I thought I could write something in that vein. If you can find that sweet spot between what the market is favoring but also what calls to you as an artist, you can’t top that combination.

Is there anything you read that was maybe less well-known than Gillian Flynn’s work, but was useful in terms of craft?

I can’t remember the chronology of it all, but I think after I read Dark Places, I started talking to John Searles and Kate White, who was the Editor-in-Chief, and who also writes suspense novels. They would mention to me books that they love and had been inspired by. Kate told me about Sue Miller’s While You Were Gone, and I kept going back to that book while I was writing Luckiest Girl. The Way I Found Her, by Rose Tremaine, was another one. She’s a poet, and the language is so beautiful. And then The Secret History—I was late to the game on that one, but I kept going back to it because I found the writing so energizing.

So many great writers have come out of journalism. Did you know that you wanted to write fiction before you got into that field?

I think I knew that I wanted my job to be writing, but a novel just seemed so daunting. In college I had taken a screenwriting course, and I thought, “Oh, maybe I could be a screenwriter.” I had an internship at Paradigm in Los Angeles at one point, and I went out there and read scripts for five weeks. But I had absolutely no concept of how I could make screenwriting happen as a career, and I really wanted to move to New York and not L.A. Maybe because I knew more people moving to New York after college.

I think I knew that I wanted my job to be writing, but a novel just seemed so daunting. In college I had taken a screenwriting course, and I thought, “Oh, maybe I could be a screenwriter.” I had an internship at Paradigm in Los Angeles at one point, and I went out there and read scripts for five weeks. But I had absolutely no concept of how I could make screenwriting happen as a career, and I really wanted to move to New York and not L.A. Maybe because I knew more people moving to New York after college.

Once I was in New York, I discovered Media Bistro, Gawker, and then I started looking for jobs in the magazine world. That was such a wonderful place for me to be because I was being paid to write, I was getting better as a writer, I was making connections, and I was around people who had published books. I could ask them, “How did you do it, and what was the process?” Writing a book is such a scary undertaking that it really helps to have someone you can turn to who has done it and is willing to say, “This is how it worked for me.”

In your interview with Jezebel, you commented on the fact that the New York Times had no interest in writing about you until you made the revelation about your rape. Why aren’t they covering books like yours?

That’s a really good question, but I think we all know the answer. Women’s writing and women’s interior lives just aren’t taken as seriously as men’s are. We’re not willing to grace that experience with the same level as gravitas. The New York Times just released its employment stats, and they now have more women editors and editors of color than ever before. Hopefully there’s a top-down effect there. When you have better representation within the people who are choosing the writers who are going to write, choosing the books that are going to be reviewed, you’ll start to diversify the books that appear in the Sunday Review.

I’m sure we can all acknowledge that gender is a factor, but is there also a curse to being too popular?

I think so. I will say this, though: when I found out that Luckiest Girl was going to debut on the bestseller list, they interviewed me for this 250-word thing they do every week with a writer that is new to the list. They were very interested in what I had to say, and I felt like they were interested in the book, but the interest really died there. I didn’t hear anything else from them until I wrote the Lenny essay about my rape.

Of course I’m very grateful for the coverage I do receive, and for the support I get from my readers. If I had to choose, I’d take the readers’ support.

I wanted to ask you a few questions about The Favorite Sister. One thing I loved about the book is the way you manipulate point of view. Brett is supposed to be the funny, likable one of the group, and that’s the way the reader sees her, but then you start to think that maybe she’s playing us. Then, at the end, we realize that she’s been keeping major information to herself all along. How did you arrive at that understanding of the character?

A lot of trial and error. I probably wrote close to 300 pages of that book that just went into the trash. I tried it from so many different points of view—from Kelly’s, from Brett’s. Eventually I landed on the idea that this was Brett and Stephanie’s story, so the reader should be hearing the most from the two of them.

Do you agree that Brett is the most likeable character? Did you expect the reader to be on her side?

Oh, no. I like Stephanie. She’s my favorite. I like characters who are brutally honest—the truth cannons. And for me, there’s something so intoxicating about someone coming undone. I wonder sometimes how more women don’t come undone, with everything that’s on our shoulders, and this intense pressure to have this air of calm and poise—I truly wonder how more women don’t lose it. In some ways, I’m living vicariously through Stephanie, and maybe that’s why I favor her.

The part that really made me sweat is where she accidentally receives an e-mail about her Author Questionnaire.

That’s what happened to James Frey. I researched everything that happened to him, because I was so interested in the nuts and bolts of how it all unraveled. On his Author Questionnaire, he’d written, “I think of this as a work of art or literature rather than memoir,” but when they started packaging it as a true story, that was when it sold. Then when he was exposed, he was able to point to that Author Questionnaire and prove that it hadn’t been this diabolical plot of his to pass lies off as truth, and the publisher had actually played a role.

I love the story you told in the Jezebel interview about actually writing the characters in The Favorite Sister with the knowledge that it would probably be adapted, and wanting to write diverse characters in order to create those roles. Can you talk about how that worked for you as a writer?

First, Luckiest Girl was optioned, and I adapted it myself. I hadn’t thought about adaptation when I was writing—I was telling this story that was very personal in some ways, and I felt like I had to get it off my chest. Then, once it was published and I realized that it was going to be adapted, I was hearing a lot of these conversations about the need for diverse representation onscreen and behind the camera. At that point, I realized that there were no diverse roles available in Luckiest Girl, and I didn’t want to continue to contribute to that problem.

First, Luckiest Girl was optioned, and I adapted it myself. I hadn’t thought about adaptation when I was writing—I was telling this story that was very personal in some ways, and I felt like I had to get it off my chest. Then, once it was published and I realized that it was going to be adapted, I was hearing a lot of these conversations about the need for diverse representation onscreen and behind the camera. At that point, I realized that there were no diverse roles available in Luckiest Girl, and I didn’t want to continue to contribute to that problem.

When I sat down to write The Favorite Sister, I hoped that I might have some of those same opportunities, and I thought that if I could write characters that would offer that kind of diversity in the adaptation process, that would be a good thing. I don’t know how much one person can really help, but it was just in my mind. And it wasn’t just racial diversity that I was thinking about—Ani in Luckiest Girl has to be very thin and very aware of her weight, but we see that kind of character onscreen all the time. With Brett, I wanted to write about a character who was in a larger body. I wanted to broaden the kinds of stories I was telling, but also to challenge myself, and put myself in the shoes of someone who’s had a totally different experience in life than I’ve had.

How did you go about writing across difference? What were you thinking about, or worried about getting right?

When I talked about writing so many drafts of The Favorite Sister and testing out different points of view, something I realized was that if I told the story exclusively from Brett’s point of view, I was relegating all the characters of color to side characters. As I’ve said, I didn’t want to do that. I wanted the reader to be fully inside Stephanie’s head and inside her experience. Part of that was trying to be sensitive and examine my own privilege, but part of it was not forcing Stephanie to take on the role of the good guy or the hero. I wanted her to be able to be just as terrible as the white women are.

Now that you’re working in L.A., what’s it like to collaborate? That’s not something most fiction writers have much practice with.

To me it doesn’t feel any different, because I’m either adapting my own work or adapting other books into scripts. With the producers I work with, the relationship reminds me a lot of my relationship with my literary agent and my team at Simon and Schuster. They’re there to give feedback, to help to shape the project. It’s maybe a little looser with a novel, because there’s not necessarily that clean three-act structure, and novels can be any length. The structure is more set in stone with a script.

But I never feel like I’m giving up creative control when I’m writing. Where I might feel that, but I haven’t gotten there yet, is in the casting process, in costume design, set design, all those things. I’ve heard from writers who’ve had their books turned into movies that those things can be real sticking points, and that you might have to fight for your vision. I’ve been able to come on as a producer for the last couple of projects I’ve worked on, so I’m assuming that I will have more say when we get to that point. It’s a problem I don’t have yet, but I’d like to have.

Since you are more in control of the business side of your work than most writers, what is your relationship with your agent like now?

Well, I have dual representation. My literary agent is at Paradigm, and my film and screenwriting agents are at CAA. It’s a different experience depending on what the project is. At the beginning, I was so green, and I didn’t have any way to compare the deals I was getting to other deals. But I trusted the people I was working with, and I trusted that I was getting the best deal and the best advice that I could get.

At this point, I am learning as I go, and I do take more of an active role in the negotiation process. I ask for things that I want. I might say, “I really want you to negotiate on that point,” or “It’s really important to me that we retain the publishing rights, and I won’t do this deal unless we do.” I guess I’m finding my voice in that area, and I’m definitely better-informed and louder than I used to be.

In my first two interviews for this series, we talked about that annoying question about whether characters need to be likeable (or relatable)—industry pressure to write characters that readers will like. From some interviews I’ve read, it seems like you’ve experienced positive reactions to complex female characters, at least from the publishing industry. Can you talk about that?

I was thinking about this a lot with the second book, when I was going back and doing the revision process. This was in 2017, when the groundswell of the #MeToo movement was beginning with the allegations against Harvey Weinstein. My reaction to it was, “Oh, maybe I should soften these characters, I don’t know if people really want read about cold, calculating, spiky women right now.” Then my editor said, “I feel like you’re trying to apologize for them, and it’s stronger when you don’t do that.” It was almost like, “Make them more unlikeable.” [Laughter.]

That was a good lesson for me. You want to be somewhat savvy to the climate that you’re in, but not so much that it distorts your creative instincts. You have to work at striking that balance. And I’m really happy that the response to my complex female characters has been largely positive. I’ve heard from a lot of women who can relate to them. I know as a reader, I find characters so much more interesting when they’re willing to expose their flaws.

You’re working on your third novel. Can you talk about it?

Well, it’s really early. I haven’t even shown pages to my editor yet. I started it at the beginning of the year, and I hope I’ll complete it by the end of the year, but it’s too early to know if it’s going to be a beast of a project or if it’s going to run a little bit more smoothly, like Luckiest Girl did. The second book was really tough, and I almost feel like nothing will ever be that hard again. Even the beginning of this one, even though I’m sure I’ll go back and revise it a thousand times, it already feels like a stronger start.

Are you on deadline? Or do you feel under pressure to put out something new?

It’s not really vocalized pressure, but I do feel this kind of constant hum: “This person is waiting for this, this person is waiting for that.” I struggled with that in the beginning, and it messed with me a little bit. But I think I’m starting to get a handle on it, and accepting that creative projects take the time that they take. I mean, most writers are not meeting the deadlines that their publishers would love for them to meet—it seems like everyone I talk to is like, “Oh my God, I’m so many months behind, I owe this person such and such.” Whether or not that’s true, I choose to believe that I’m in good company.