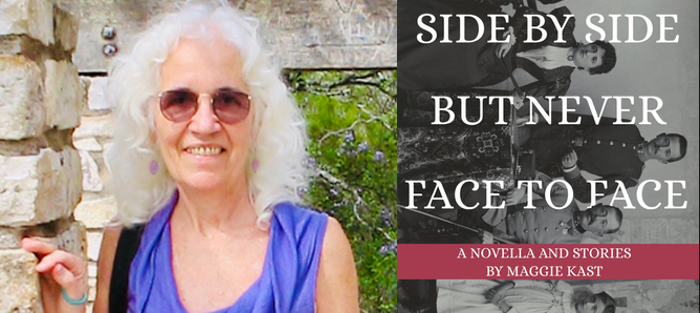

Maggie enters my apartment, where we’ve planned to do the interview, noiselessly, gracefully, a habit perhaps from her dancing career. Although she is long retired from dance, it’s easy to see her as she was back then with her lean, light body, long neck and arms, and her straight back and pure white hair, making her seem—forgive the cliché—ageless.

Maggie’s second career is that of a teacher and a writer, and she has just published her third book and first story collection, Side by Side but Never Face to Face, combining memory and invention in a quest to understand how the world works from her current vantage point. In 1977, when Maggie and her husband were vacationing in Jamaica, they were in a car accident that took the life of their three-year-old daughter. That loss galvanized the seeker in Maggie, turning what may have been an intellectual quest for understanding into a matter of emotional life and death. The stories in this book are interrelated, centering on the lives of a couple very much like the author and her husband. And amidst the finely wrought drama of their lives before and after the loss, giving it form and meaning, is the longing for illumination, for a glimpse of the system in which such depth of sorrow can occur.

Interview:

Sharon Solwitz: I’ve always loved your work, but this book felt many cuts above the last thing I read. The only story that made me pause was the final one. Until then I just bobbed in the current of your language, your revelation, your insights and dramatizations and thoughts, and felt I was getting to know you in a way that I hadn’t done before. I looked at how you went into the mind of your husband, whom we’ve talked about over the years. And now you’ve dramatized him, made him into a complex character. It feels, well, literary.

Maggie Kast: Well, Sharon, coming from you that means a huge amount, because the material goes back a long way, though some of the stories are new. But listening to you I think you must be talking about somebody else. I wonder, “How did my stories get to be this thing?” Maybe it was from working with Garth Greenwell at Writing by Writers Manuscript Boot Camp. He saw the manuscript as a unified whole, like a novel, and insisted that characters mentioned in one story should be accounted for in another. At a much earlier stage, I consulted with Kevin McIlvoy about the novella, and he suggested a retrospective, third-person point of view, which gave the narration a necessary distance.

How did you decide to order these stories? Was there a process or an idea that you were working on? It’s a very emotional book, but it’s also conceptual in terms of spirituality and the relationship of human beings to their fate, God, and how they manage to live in the world.

I put them together on instinct. I’ve been with most of these stories for a long time, and then I took them to Writing by Writers. Orison Books had already accepted the manuscript, but my writing group hadn’t given it the critical scrutiny they usually give to new work. So the first question I asked my Writing by Writers’ cohort was, “Do all these stories belong in here?” We all agreed rather quickly that there were two that did not belong, because they were peripheral to the family story.

Grief is one of the things that you never move on from, despite that awful phrase, and that loss permeates the book. It’s the couple’s first big loss and comes at a time when you, autobiographically, had never experienced loss on that scale. The accident itself is chronicled in the opening story, “The Cry of the Patoo,” but it returns in the novella at the end of the book. That was a very bold move, to bring up an old story but with a slightly different angle. How old is Greta when she is seeing the psychiatrist, Hal, in the novella?

Grief is one of the things that you never move on from, despite that awful phrase, and that loss permeates the book. It’s the couple’s first big loss and comes at a time when you, autobiographically, had never experienced loss on that scale. The accident itself is chronicled in the opening story, “The Cry of the Patoo,” but it returns in the novella at the end of the book. That was a very bold move, to bring up an old story but with a slightly different angle. How old is Greta when she is seeing the psychiatrist, Hal, in the novella?

She’s the same age I am, and was in her fifties when she first saw Hal.

So it’s thirty-some years after the death of her daughter, and it was something that had enough staying power to justify talking about it and then writing about it again.

I think when I was working with Kevin McIlvoy, he said Greta should have an affair, perhaps right after the accident, so then I knew I would have to put the accident in the novella, as well. At that point I said to you, “Sharon, I seem to be writing the same thing over and over.” And you said, “Well, that’s okay, if it’s different, what you end up with.” So I tried to make it as different as I could, with a different point of view and some different events in the wake of the accident.

I was surprised to see it come up again, but I gleaned more. Also, “The Cry of the Patoo” is from Manfred’s point of view, and now we see the accident from Greta’s. Can I ask you what guided the first story’s approach?

I was inspired by “The Death of Ivan Ilyich.” You remember, when he realizes he is seriously sick he experiences himself as a child, asking something like: “How could this happen to little Ilya?” So I had the narrator, Manfred, right after the accident in which Katrina was killed, relive his childhood. German Legends like Rübezahl, the giant of the Schwarzwald, I had to research. I’d heard of him, but I didn’t know any of his stories. I had to write to Austrian friends and get a book and read up on it, and then I wove it into the story.

Here’s a question that I’ve been dying to know the answer to. You did research that taught you things you didn’t know about your husband, with whom you’d spent thirty years. Did you learn anything that changed your conception of him or your feelings about your relationship with him?

The only way I can answer that is to talk about something very recent, which hasn’t made its way into anything published. I didn’t feel any changes, although when I wrote the story about Manfred’s adolescence, I was imagining my way into someone I never knew.

He’d spoken about running from the brownshirts, so you probably had some history and details from him.

Yes. But recently, for the first time, I went back and looked at some of the correspondence between my husband and his parents during his first marriage, when they were all three new immigrants to the U.S.

You saved them?

I didn’t save them. My mother-in-law saved them. She saved everything because she was so mad at everyone. I didn’t intend to ever look at them again, because the man of the letters was not the man I married. He used to tell me he was not the same person he’d been, and now I saw it was true. He had been so embroiled in this tangled relationship with his parents. They were constantly making declarations of love to each other followed by bitter recriminations, attacking and defending. But recently, while I was working on a food essay about the cooking I learned from my mother-in-law, I decided to include brief excerpts from the letters, and I had to look them up all over again.

I still want to know: how did you integrate the husband, who had been so attached to his parents that he could write them a virtual love letter, into your understanding of how he was as a husband to you? One of the things I love about Alice Munro stories is that many of them are about the impact of memory on the protagonist’s self-narrative. In her story “What Is Remembered,” the narrator learns about the death of a man she had sex with. She was married then, and they had only one encounter, but she has cherished the memory as something, in a weird way, sacred. She thinks that it might be what has kept her married to her husband until the end of his life, that without it she would have left him for more wild adventures. And then the news of the lover’s death stirs a further memory, something she has repressed until this moment. When they’re parting, she wants to kiss him goodbye, and he refuses. He says, “I never do.” Which of course is really nasty, but that’s not what the narrator is thinking. She’s wondering how this new memory will change the way she is currently living her life.

I still want to know: how did you integrate the husband, who had been so attached to his parents that he could write them a virtual love letter, into your understanding of how he was as a husband to you? One of the things I love about Alice Munro stories is that many of them are about the impact of memory on the protagonist’s self-narrative. In her story “What Is Remembered,” the narrator learns about the death of a man she had sex with. She was married then, and they had only one encounter, but she has cherished the memory as something, in a weird way, sacred. She thinks that it might be what has kept her married to her husband until the end of his life, that without it she would have left him for more wild adventures. And then the news of the lover’s death stirs a further memory, something she has repressed until this moment. When they’re parting, she wants to kiss him goodbye, and he refuses. He says, “I never do.” Which of course is really nasty, but that’s not what the narrator is thinking. She’s wondering how this new memory will change the way she is currently living her life.

I’d always felt, when my husband was alive and very rough with his mother, that there must be some middle way to handle her, some way he could modify her aggression without being entirely rude. What I learned from the letters was that there was no middle way, and I was grateful that my husband had gained control of the relationship. What has changed even more over many years is my understanding of the social, political, and cultural forces that made him and his family the way they were. Germany was a land of opportunity for Jews from Czernovitz, or further East, like Galicia, beyond the Pale. Persecution dated back to the 18th century and beyond, and that persecution had eradicated family and heritage. Then Austria and Germany, lands of opportunity for Manfred’s grandparents, turned into a murderous country in just two generations.

To me one of the most interesting things in fiction is power relationships, how they shift, balance, and rebalance. Domestic politics. It can enlarge a domestic story and make it political. But all this is apart from the spiritual quest, one of the major parts of your story. First, the death of Katrina is catastrophic for both Manfred and Greta.

You and I have that in common, unfortunately. Membership in the club no one wants to join—your story “Alive” about the family with a child who has cancer.

[Pause]

We’re lost for a while. You look for God, yes? Me, I painted rooms in our house, I had to keep moving. And then, for some reason, we write about it.

Yet Greta then also has to weather the death of Manfred, who’s been her one-and-only man since she was nineteen. My students often ask, “Can’t we have a happy short story? Why do they always have death in them?” Sometimes I say, “Isn’t that what it’s all about? Sex and death?” And that’s what the narrator, really the author, is trying to do, to find a way to live in a world full of what hurts.

As you well know.

Yes. And I see similarities in the ways we write, or the sources from which we write. Although I have a kind of random chance attitude: “If there’s a God, please show me.” You do more soul-searching. Not in a pedantic way, but somehow making that quest something I want to follow. Could you tell me something about your quest to find a way to live alongside the worst that can happen?

Yes. And I see similarities in the ways we write, or the sources from which we write. Although I have a kind of random chance attitude: “If there’s a God, please show me.” You do more soul-searching. Not in a pedantic way, but somehow making that quest something I want to follow. Could you tell me something about your quest to find a way to live alongside the worst that can happen?

It took a lot of different forms over time, all the way from what almost seems like denial, like feeling that the tie between myself and my daughter was so strong that it couldn’t be broken, which was how I felt when it first happened. It made me question my whole view of the world. They call that “widening horizons,” like the world is bigger than you thought before. Then it took a more practical form, discovering a community and a ritual and experiencing that emotionally. And then intellectually. I went to Catholic Theological Union and studied how people came up with these ideas.

I want to go back to the first thing that you said about being connected, that unbreakable tie. When Jesse died, I was lying next to him and I was listening to him breathe and it got slower, rasped, and then stopped. My impulse was Jewish. I put my arms around him and said the “Shma.” Hear, O Israel… I wanted to connect him to something larger, even though I wasn’t a believer. Later I had a dream where he was full of light, and I was afraid if I touched him he might disappear.

I read about the moment of death in your story, even though you re-imagine it as the father who does this. Different people interpret experience differently. Another person might have taken Jesse-full-of-light as a spiritual experience in itself.

Why do you think you were open to a spiritual interpretation?

I’ve always had an urge to transcend, to go beyond, and that motivated my dancing a lot. It didn’t have any names, like God or spirit or anything, but there was this sense that I could be more and other and different from what I was by being able to leap across the floor or have that feeling of fully inhabiting my body. I liked to visit churches and temples, but I experienced the spiritual mainly through the arts.

For me it was magical stories and fairy tales, like Mary Poppins. I wanted to be physically transported into another dimension. And in the sixties, the idea that anything could happen—I embraced that wholeheartedly. There were no limits to my development or experience, and I loved that feeling. Like dreams of flying. So how has your faith changed over the years?

Well, it’s gotten much less hot.

Which period of your life was it most passionate?

Right after my daughter died. And then the three years until I entered the Church. That was all a very intense period of search. But I never became anything other than a 20th-century realist. I still go to Mass every week, but I’ve never questioned science or taken up conspiracy theories. And while I was studying at Catholic Theological Union, I had this intense relationship with a spiritual director, as that chapter in the novella describes.

And I can see why Manfred, the character based on your husband, was pissed. You mention jealousy, but it was a spiritual, intellectual, and emotional jealousy, rather than sexual.

And that was made more complicated by his former Catholicism, in an Austria where the Church was very anti-Protestant and anti-Semitic.

So where are you right now?

I’m reading a book that I love by Christian Wiman, He Held Radical Light. It’s a book about poems, other people’s, and his own spiritual journey. He says he doesn’t believe anyone who claims absolute belief or absolute atheism, and that’s about where I am. Many of the poems in the book express their own faith in the complex way that great art does.