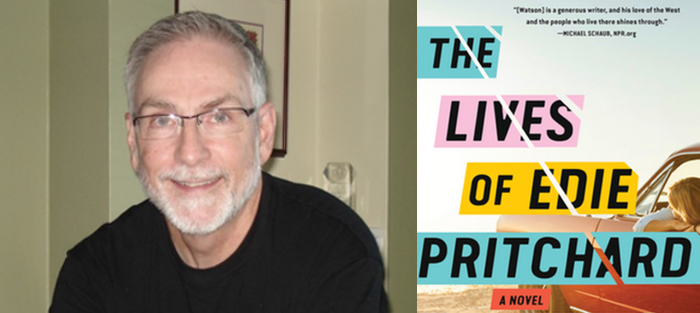

Larry Watson is an excellent listener. I first met him when I took his Introduction to Fiction class as an undergraduate at Marquette University, then his writing seminar, and then an independent study where we sat in his office once a week to discuss my work. When I try to explain his influence on me as a young writer, I could point to the insights he shared or his careful prodding to dig deeper into a scene, but more than anything it was the way he let conversations flow over him. Larry’s attention and sincerity not only affirmed that my words mattered; they are the traits of a remarkable teacher, mentor, and writer.

Larry’s fiction too is filled with that ear for the world around him. It’s clear in the way he writes with such care that this is a man who has spent his life listening both to his nostalgia for the Montana/North Dakota area and the pressures this culture can place on people. Following his long string of Western classics that include Montana 1948, Let Him Go, and As Good as Gone, his new novel, The Lives of Edie Pritchard (Algonquin Books), follows a memorable main character with an important view of a town that made but couldn’t define her. We talked over email about the book.

Interview

Michael Welch: I remember the last few times we’ve caught up you mentioned that you were working on a novel primarily consisting of dialogue. I have to say after seeing the project come to fruition, it makes for both an intimate and cinematic read. What inspired you to try this structure?

Larry Watson: Well, I have to say “intimate” and “cinematic” are two qualities I strive for in my fiction, but it’s not exactly fair, is it, to steal your question for my answer? And really, the answer to why the novel is written this way is the result of long-developing and complicated decisions about both narrative technique and life.

I’ve said on many occasions that I probably learned too well the “show don’t tell” dictum. Its application was brought home to me when, as an undergraduate, I took a course in Hemingway, and the professor, a Hemingway scholar, pointed out how little exposition Hemingway used in some of his stories. “The Killers” and “Hills Like White Elephants” were almost all showing—action and dialogue. I was just beginning to write fiction myself, and I might have mistakenly believed that those stories were masterpieces because they had no exposition.

But then and now exposition has given me trouble, and my preference is almost always for scene over summary. I also believe that nothing engages readers like dialogue and action. Elmore Leonard famously said that in his fiction he left out the parts that readers skip. And readers almost never skip dialogue or action, but they might bounce quickly through a passage of exposition. Since I have a mortal dread of boring readers, I’ve tried to follow Leonard’s example.

But then and now exposition has given me trouble, and my preference is almost always for scene over summary. I also believe that nothing engages readers like dialogue and action. Elmore Leonard famously said that in his fiction he left out the parts that readers skip. And readers almost never skip dialogue or action, but they might bounce quickly through a passage of exposition. Since I have a mortal dread of boring readers, I’ve tried to follow Leonard’s example.

Apart from narrative technique, I’ve also come to believe it’s our actions and our speech that reveal who we are, at least to others. Maybe we have a different identity in our inner lives, but others know us from what we say and do, not from our thoughts and feelings, which can be guessed at or extrapolated but not really known.

In an earlier novel, Let Him Go, I tried to minimize, if not eliminate, the differences between the different narrative modes, partly by trying to convey an inner state, for example, by describing something in a certain way. Hemingway, in those stories I mentioned, uses the objective or dramatic point of view to accomplish his effects, and while that’s what I initially intended for Let Him Go, I eventually settled on a kind of hybrid omniscience. I had the objective point of view in mind for The Lives of Edie Pritchard, and for long stretches I accomplished that. Finally, however, there were places where a character’s inner state, invariably Edie’s, was necessary, and fortunately I had an astute editor who pointed out those places.

Was there anything particularly liberating or challenging about composing a story largely through dialogue?

It was both. It was challenging in the way that it’s challenging to write a sonnet. Of course, it’s not as though a poem is going to be good simply because it’s a sonnet. But trying to meet the demands of the form can sometimes push writers to go beyond what they think they’re able to do—or what they usually do. That happened for me. But even writers not planning to use the objective point of view might try to do so for a passage or two. When writers can’t simply tell the reader something but must convey the information dramatically, they might come up with something more vivid and compelling. This is what filmmakers must do, to go back to your comment about a cinematic style.

Your depictions of Montana and North Dakota are succinct, and also packed with tenderness, affection, and even awe. What about this setting continues to inspire you now that you’re ten books in and a long-time Wisconsin resident?

I don’t know if it’s true that fiction writers create primarily either from observation or memory, but if it is, you could put me in the memory camp. (Needless to say, both groups work from imagination.) I count on memory to work as a kind of filter, and I trust that what sticks in the filter, even if I don’t know why it’s there, is there for a reason and is important both to my psyche and to my writing. My fiction is full of those filter details. And it matters to me not in the least that my memory might not be accurate. That is, the Dairy Queen might have been on a different street and that stand of woods might have been west of town not east, but it only matters to me what works for the fiction. And I trust that the way I remember leads me toward what works—it has significance, even if I’m not fully aware of what that significance is.

Now, to work from memory means I have to be removed from a place, and my wife has often said that once we leave a place then it becomes fair game for my fiction.

Those landscapes that you mention made powerful impressions on me, and my responses to them—to the northern plains, to Montana mountain ranges, to the Dakota Badlands—have lived in me in exactly the way you say, with affection and awe.

I’ve tried, however, not to let a sense of nostalgia or the feelings of my younger self govern my descriptions of place. It’s easy for me to remember what I felt when I first saw the mountains, and which I feel on every successive sighting, or to recall the prairie world I grew up in, but in fiction I’m a realist, and I try not to write about an idealized world. It probably helps that my fiction is often set in the parts of Montana and North Dakota that are seldom pictured on postcards or calendar pages.

You’re also so skillful at describing how this town changes throughout the years—the buttes turned to subdivisions, the once promising, now middling strip malls, and the emerging oil boom. Do you ever consider your settings among your cast of characters as you write?

No, I’m too literal-minded for the kind of fiction you refer to. I’ve often heard writers say that place functions for them like a character, but for me places are places and people are people. That said, I have to add that the two are in almost constant interplay. We are who we are because of where we are—and where we’re from. And places are affected by people, both in physical and perceptual ways. I’ve seen stretches of prairie both before and after the oil boom, and the presence of those wells, which look like giant prehistoric birds constantly dipping their beaks into the earth, not only change the way landscape looks but how we think and feel about it. We change the environment, and that altered environment changes us, a truism obvious to all of us when we look at clouds of polluted air, but it applies also to the new housing development built on the field where we used to play baseball. Humans need houses to live in, obviously, but if we remember the fun we once had playing there—and never can again—it’s hard not to feel a sense of loss.

No, I’m too literal-minded for the kind of fiction you refer to. I’ve often heard writers say that place functions for them like a character, but for me places are places and people are people. That said, I have to add that the two are in almost constant interplay. We are who we are because of where we are—and where we’re from. And places are affected by people, both in physical and perceptual ways. I’ve seen stretches of prairie both before and after the oil boom, and the presence of those wells, which look like giant prehistoric birds constantly dipping their beaks into the earth, not only change the way landscape looks but how we think and feel about it. We change the environment, and that altered environment changes us, a truism obvious to all of us when we look at clouds of polluted air, but it applies also to the new housing development built on the field where we used to play baseball. Humans need houses to live in, obviously, but if we remember the fun we once had playing there—and never can again—it’s hard not to feel a sense of loss.

I should also say that I think of my fiction as taking place more under roofs and ceilings—the great indoors—than under the Big Skies of the region. The drama of my characters’ lives plays out in the confined spaces of cars, bedrooms, living rooms, and kitchens. So much for the wide open spaces of the West….

This novel seems like the perfect follow-up to As Good As Gone, which concerns one of the last true cowboys in his town. The Lives of Edie Pritchard is also haunted by that Old West mythology, as we see a number of male characters fumbling for control, but ultimately looking more like boys playing pretend. How did you approach breaking down these assumptions about the Western novel?

It wasn’t my intention that this novel fit within or kick against the tradition of the Western novel, but it’s hardly possible to set a fiction in that region without at least glancing in the direction of those durable myths of the rugged, self-reliant, taciturn, solitary Western hero. The mythology, both in literature and in life, has been exposed, rejected, interrogated, refuted, and deconstructed, yet somehow keeps chugging along. Westerners, especially males of the region, live in the shadow of the myths, no matter that they see how false they are. At some point in the composition of The Lives of Edie Pritchard, I realized that if the fiction were set in the nineteenth century, the characters would have had particular traditional roles. Roy Linderman would probably be an itinerant horse trader, his brother Dean would be the insecure young man who seeks a violent showdown in order to prove his manhood, and the Norris brothers would be young outlaws, roaming the West and looking for the main chance.

Edie is incredibly perceptive about the world around her, and her perspective unlocks a different way to explore this cowboy mentality. Can you talk a bit about your process in creating and developing this character?

Women, it seems to me, while not exactly immune to the power of the mythology of the West, are much less susceptible. And Edie recognizes that the image of what a man should be in her part of the world is ridiculous in many respects, but no less hazardous for that. That the men in her life frequently cling to an outmoded, even immature, code of conduct frustrates and angers her. But Edie understands she has to live in that world.

It’s also clear that the character of Edie was written with a particular care. How did you approach centering a novel on a character with a far different lived experience than yourself?

I wouldn’t be lying if I answered this with one word. Imagination. I imagined what Edie Pritchard would say and do (and occasionally think and feel) in different situations. But I had help. Edie is a strong woman, and I’ve been around quite a few strong women in my life. Edie isn’t my wife, but my wife was a willing template for Edie. If Edie did something that I could—hypothetically—see my wife doing, I felt as if I were on pretty safe ground.

I wouldn’t be lying if I answered this with one word. Imagination. I imagined what Edie Pritchard would say and do (and occasionally think and feel) in different situations. But I had help. Edie is a strong woman, and I’ve been around quite a few strong women in my life. Edie isn’t my wife, but my wife was a willing template for Edie. If Edie did something that I could—hypothetically—see my wife doing, I felt as if I were on pretty safe ground.

That Edie is the novel’s main character was something of a surprise. In my original plan the Linderman twins were the main characters, and the plot was going to be about two men in love with the same woman. But Edie just came to the fore. She was a fascinating character to create and follow.

Which authors do you return to inspiration? Are there any recent works that have particularly excited you?

Every year I reread James Salter’s Light Years. I write nothing like Salter (unfortunately), but his writing evokes something in me like almost nothing else. And the novel’s magic works on me every time. I recently reread E. L. Doctorow’s Ragtime. I was in Mr. Doctorow’s class at the University of Utah when he was there for a term as a visiting writer. Ragtime came out during that time, and I heard him read from the novel and I read it soon after its publication. I thought it was magnificent then, and I appreciated it even more this time.

A few recent reads knocked me out. Daniel Mendelsohn’s The Lost is an amazing book, part detective story, part history, and part memoir. Louise Erdrich’s novel The Watchman is up to her usual high standards. Philip Roth was one of my favorite writers, and I reread his novel Nemesis to see what his genius had to say about living through an epidemic. Roth’s plague was polio, but the book is no less relevant for our strange, difficult time.

What are you working on next? Can we expect more plays with structure and process in the future?

After I finished The Lives of Edie Pritchard, I wrote a few short stories in a similar mode—objective point of view fictions told using only action, dialogue, and a little description. I don’t know whether the stories worked or not.

I’m working on a new novel that’s more conventional in terms of narrative technique, though everything I write I consider an experiment of some kind. Some experiments declare themselves as such more than others, however, and I never want the experiment to get in the way of the story.