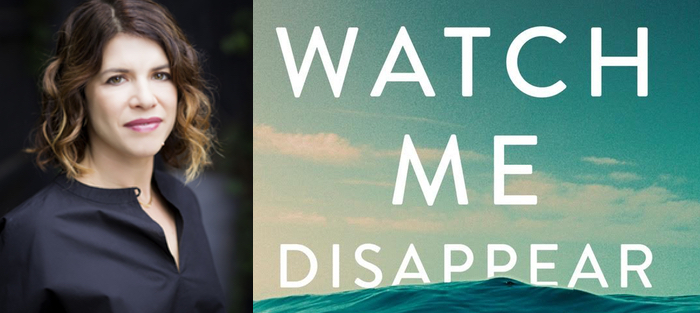

During the two years I spent on the Central Coast of California, I couldn’t stop raving about it to friends back home on the East Coast. It was seventy-five degrees all year long! The beach was only fifteen minutes away! I had a eucalyptus tree in the back yard! The atmosphere really was idyllic, and yet as time went on I found, as many visitors to California have found before me, that the aesthetics of my environment didn’t necessarily translate into personal happiness. In fact, the brighter the weather outside, the darker my inner life seemed by contrast. It’s an atmosphere familiar to any fan of California noir, and one that Janelle Brown exploits to great effect in her third novel, Watch Me Disappear.

Watch Me Disappear (Spiegel & Grau) is the story of Billie Flanagan, a Berkeley housewife and mother of one, who goes missing during a solo hike in the Desolation Wilderness. Billie’s story is told from the alternating perspectives of her husband, Jonathan, and fifteen-year-old daughter, Olive, who offer very different perspectives on the missing woman. On the strength of a eulogy that goes viral on social media, Jonathan sells a memoir about a happy marriage cut short by tragedy. But the more he researches his wife’s past, the more he has cause to question the narrative he’s created. Olive has a more realistic view of her mother, but while Jonathan begins to move on, the intensity of his daughter’s grief leads the reader to wonder whether she’ll be able to recover from this loss.

As a storyteller, Brown avoids easy answers and pat narrative solutions. Watch Me Disappear provides everything that I want in a suspense novel—not just a fast-moving story, but also complex and believable characters, as well as insights about gender and motherhood that are as sharp and surprising as anything I’ve come across in literary fiction. In the second of my series of interviews with women crime writers, I talk to Janelle Brown about how she did it.

Interview:

Polly Atwell: I’ve read some about your career, but for the benefit of our readers, can you talk about how you came to writing?

Polly Atwell: I’ve read some about your career, but for the benefit of our readers, can you talk about how you came to writing?

Janelle Brown: Well, I wanted to be a writer ever since I was a kid, and I had that goal very much in mind all through school. Post-college, I worked in journalism. I was in San Francisco in the early dot-com era, and I worked at Wired, and then I worked at Salon.com. Then I quit to write fiction, and did a lot of freelancing while I worked on my first novel, All We Ever Wanted Was Everything (2008).

So many great fiction writers have come out of journalism, so that makes a lot of sense as a career path.

Yeah, I got tired of having to write the truth. [Laughter.] I wanted to be able to make things up.

I think of Watch Me Disappear as a crime novel, even though there’s some uncertainty about whether a crime has been committed. But your first two novels weren’t in that genre. How did you start to think of yourself as a crime writer?

When I was writing Watch Me Disappear, I didn’t really think of it as a crime novel at all. It wasn’t until I turned it in that I realized, “Oh yeah, I’ve written a book with a mystery element to it,” and I started rewriting it in that direction. Then, when my editor read it, she said, “Oh, you’ve written a suspense novel.”

I feel like genre is one of those terms that is becoming less clear and even less relevant all the time. There are definitely books that fall very clearly into one genre camp, like a John Grisham novel or a Danielle Steele novel—it’s very easy to classify them. But I think more and more fiction is really about storytelling that transcends genre, or has genre elements but is not strictly a genre novel. So I guess that’s where I feel like my last book lands. As I was writing this novel, I was thinking about it as being like my first two books—a page-turner about a family. My first two books were page-turners as well, though they weren’t necessarily in the suspense genre.

That’s interesting—I think often writers tend to think of genre as more of a marketing decision that something that really matters in the process. Now that you’re working on the next book, do you feel any pressure to stay in that genre?

I would say yes and no. As a reader, I love a story—I love a good page-turning story. I do love a slow, meditative novel as well, but the books that really grab me are the ones where I really want to know what happens next, but also are elegant, and smart, and aren’t just about shoehorning a character into a plot. In that sense, I feel like all of my books are going to be leaning toward a “What happens next?” kind of plot.

With the success of Watch Me Disappear, there is a certain amount of nudging from my publisher: like, can you do it again? But I guess I don’t ever want to write the same book twice. For me the interesting challenge would be to write another book that has suspense elements and can be sold as a suspense novel, but is also different from what I’ve already done. My publisher would love me to write in the suspense genre because it sells well, but they’re also happy to let me do whatever I want to do as long as it’s fun and readable.

A lot of reviews and interviews I’ve read commented on the setting in Watch Me Disappear. I lived in California for several years, and the sights and smells that you evoked seemed so perfect to me. Do you have any thoughts on writing those descriptions? Did you go out and take notes?

I definitely will try to visit the places that I’m writing about, but I’ve also mostly written about places that I know well already and have a very distinct sense of place for me. They’re already ingrained in my head, I guess. I’ve lived in California my whole life except for one year I spent in London, and I’ve lived all over the state. For me, California is so evocative, so it’s easy for me to write about it. I actually hadn’t been to Santa Cruz for about ten years before I went out there to check out locations when I was working this novel, but when I got there I realized I actually remembered it really clearly. These places stay with me.

While we’re on the subject of craft, I thought it was so fascinating what you did with Jonathan’s memoir. It changes over the course of the novel, so the more honest he gets with himself about his marriage, the more fun the memoir is to read. How did that structure come to you?

That actually came to me pretty late in the process. It wasn’t part of the initial idea. The book is about how we make memories of other people, and how we see what we want to see, and we remember what we want to remember. Jonathan and Olive both have to confront these memories that they’ve avoided, because they’d rather focus on the positive things. Especially when someone dies—I’ve heard this from people who are grieving, how you want to remember the best of the person who’s been lost.

That actually came to me pretty late in the process. It wasn’t part of the initial idea. The book is about how we make memories of other people, and how we see what we want to see, and we remember what we want to remember. Jonathan and Olive both have to confront these memories that they’ve avoided, because they’d rather focus on the positive things. Especially when someone dies—I’ve heard this from people who are grieving, how you want to remember the best of the person who’s been lost.

So I was looking for a way for Jonathan to confront his evolving memories of his wife, but I didn’t want to do a billion flashback sequences. Then I had one of those moments of inspiration where I thought, “He’s writing a memoir, and we get to see the memoir change!” It was really fun to write that, and to develop his first-person narrative, and also the process of him getting more and more brutally honest and dark as he’s writing it.

His view of her is distorted at the beginning of the novel, and the more he learns, the more his perspective comes into focus.

Well, I’ve watched friends go through things where they’ve learned about deception that their spouses or lovers have been carrying on behind their backs. And there’s always that moment where you look at that situation with a completely different eye, and see things that you didn’t see before, or interpret them in a different way than you used to, and the lightbulb goes on. So I wanted the reader to be with him as he goes through that process.

There’s a question for much of the novel about whether Billie has been abducted or harmed in some way, or whether she’s just chosen to leave her family. Even before we learn the answer, we can see that she’s been neglectful of her child in certain ways. Did you find that hard to write about?

Well, it was definitely an evolution, as I was writing the character of Billie, to let her be the person that she needed to be. As a mother, there is darkness that is difficult to confront, and very difficult to talk about in public. It’s not all happiness and light, and there are moments when you want to run screaming. When I was writing this book and talking to other mothers, we’d have these brutally honest, confessional moments where they were telling me their fantasies of what they would do if they didn’t have children, and I kind of realized that yeah, you know, it’s not that unusual to have these feelings.

The thing about writing difficult characters that I really enjoy is that they can do the things you can’t do yourself. I have a hard time not being polite, so I love writing a character who can be really rude and do all the things that I would never have the guts to do. It’s a catharsis, in a way, and it’s also a way of being able to explore those feelings and then put them in a drawer.

Which is so much better than just pretending we don’t have those feelings, because everybody does.

And the books I love the most are always the ones that explore the dark parts of the psyche. Nice women make great friends, but they don’t necessarily make exciting protagonists. For me the most interesting books are where the characters are really flawed or even downright fucked up.

In the previous interview I did for this series, I talked with Amy Gentry about the idea that women in novels have to be relatable or likeable, and then I found that you’d written about that too. Do you hear about that from your agent and editor, or from readers?

Absolutely not. My editors and my agent have always been super supportive, and I’ve never had anyone tell me to make a character more likeable. That said, it’s not about making them likeable, but about making them understandable. I think it’s okay not to like a character as long as you understand why they are the way that they are. I think that’s the challenge and also what’s most interesting as a writer—taking someone who’s complex or even downright unpleasant and bringing them to life in a way where your reader can be like, “Okay, maybe I don’t like this person, maybe I would never want to be friends with them, but I understand them in a way I didn’t when I started this book.”

Absolutely not. My editors and my agent have always been super supportive, and I’ve never had anyone tell me to make a character more likeable. That said, it’s not about making them likeable, but about making them understandable. I think it’s okay not to like a character as long as you understand why they are the way that they are. I think that’s the challenge and also what’s most interesting as a writer—taking someone who’s complex or even downright unpleasant and bringing them to life in a way where your reader can be like, “Okay, maybe I don’t like this person, maybe I would never want to be friends with them, but I understand them in a way I didn’t when I started this book.”

I think at its best, that’s what fiction can do for us—open up those psyches that we’d never have access to otherwise. And that’s not always going to be pleasant.

Exactly. You know, the thing that drives me absolutely bonkers is when I’m reading a book where a character just does things, and you’re like, “But why? Why is he such a monster?” Like, okay, you have this sociopathic character, and that’s the whole explanation for their behavior: they’re just a sociopath. But I’d like to have a little bit more explanation of how they got to be that way.

Can you tell me a little about what you were reading while you were writing Watch Me Disappear?

Well, it took me so long to write that I read a lot of books. I read a lot of Tana French! I read anything that had a missing woman in it, because I wanted to make sure I wasn’t doing the same thing. I read a lot of Megan Abbott, Gillian Flynn—all the usuals, I guess, if we’re talking about crime fiction. But I also really enjoyed books like Everything I Never Told You, by Celeste Ng, which is about a family but has this mysterious death at its center. Fates and Furies, by Lauren Groff, was also very helpful, because it was about the strikingly different points of view between a husband and a wife.

Is there anything you’re excited about that’s coming out soon, or that has come out recently?

I just finished powering through Karen Thompson Walker’s books, which aren’t really crime novels—they’re more supernatural, apocalyptic fiction. The Dreamers just came out, and I just reread her first book, The Age of Miracles, which is great.

I blurbed a book that’s coming out soon that I really enjoyed. It’s called Miracle Creek, by Angie Kim. It’s out in April, and it’s kind of a courtroom thriller. It’s about a possible crime, and the investigation of that crime, but it’s also about this Korean immigrant family. It’s a beautifully written novel, and it’s also a great example of genre-crossing. It’s a crime novel and a suspense novel, but it also reads like literary fiction.

I also just blurbed the new novel by Laura McHugh, The Wolf Wants In. She’s written a bunch of crime and mystery novels, and I really enjoyed that one.

To be honest, I’ve read some new works by authors I really like that I actually wasn’t that excited about. It’s hard to write books, and every author has highs and lows. Especially when you’re having to write a novel every couple of years to pay the bills—it’s a challenge. Hats off to any author who manages to write something readable!