“The only obligation to which in advance we may hold a novel,” wrote Henry James in The Art of Fiction, “is that it be interesting.” In the past couple of years, I’ve noticed that the novels that seem to interest me the most—the ones that teach me the most about the craft of fiction, and have the most interesting things to say about the human experience—are crime novels by women. Today on Fiction Writers Review, I’m beginning a regular series of interviews with women crime writers who exceed James’s requirement to interest the reader, keeping pages turning while also telling us new and sometimes uncomfortable truths about women’s experience.

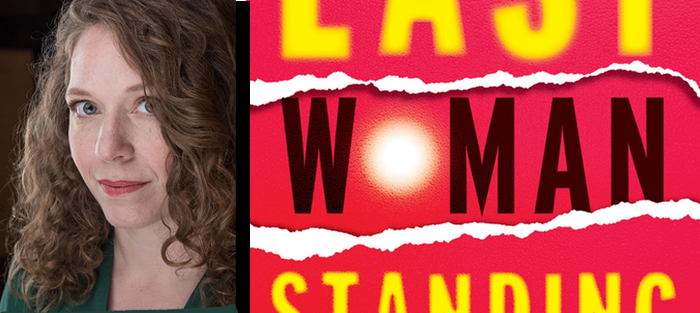

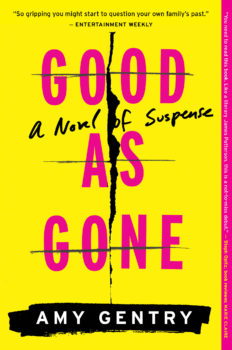

Our first interview is with Amy Gentry, author of Good as Gone, which was a New York Times notable book, and Last Woman Standing, which was published last month by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Last Woman Standing follows comedian Dana Diaz as she struggles to find professional success at the open mics of Austin, Texas—a process that becomes suddenly, improbably easier when she meets computer programmer Amanda Dorn. Like Dana, Amanda has a long list of grievances from her past, and she suggests that she and Dana form a revenge pact that will allow them to get back at the men who have hurt them without implicating themselves. When the plan goes awry, its failure forces Dana to reckon with her own capacity for violence and retribution.

Though I’ve never met Amy in person, speaking with her about the novel felt like chatting with a friend. She’s funny and insightful, and has thought deeply about the crime genre as both a writer and a reader.

Interview:

Polly Atwell: When we were e-mailing, you said this was a great time for women writing crime, and I totally agree, but why do you think that is?

Amy Gentry: Women have always been a strong force in crime, so I don’t want to make it sound like this was something really new. But I think after Gone Girl, in particular, there was kind of an explosion of interest in women writing crime. And certainly opportunities for women writing in that genre really skyrocketed, because publishers were eager to get more Gone Girls out in the world.

You almost can’t go far enough in attributing the current appetite for domestic and psychological suspense to Gone Girl—to that one book. It really did change the landscape. And there were people like Sarah Weinman, who had been working in that field for a while, but their voices got more prominent in this new era. So all of a sudden there was this conversation about crime fiction that was really led and driven by women.

If you want to ask why Gone Girl was such a surprise overnight success, I think it captured something that was already bubbling in the zeitgeist. I think the cultural moment that we’re in right now, the Me Too or post-Me Too moment, has been building for quite a while, and I would put Gone Girl as one of the early signs in that sea shift. People seem to be ready to hear about women’s experience of the world in a way that I don’t know that they were before.

What made you want to write in this genre? I’m talking about positioning for publication and marketing as much as the kind of story you tell.

Well, I didn’t really want to write in this genre. I had been working on my first book, Good as Gone, for a couple of years, and I had always thought of it as kind of a literary family drama. It did revolve around a kidnapping and a missing girl, but it took me a surprisingly long time to realize that that put it in the crime genre. I had just come out of a Ph.D. program in English, and I was reviewing literary fiction for the Chicago Tribune, and that was the world I was steeped in. And I didn’t really read a lot of crime, and I didn’t think of myself as liking crime particularly.

Well, I didn’t really want to write in this genre. I had been working on my first book, Good as Gone, for a couple of years, and I had always thought of it as kind of a literary family drama. It did revolve around a kidnapping and a missing girl, but it took me a surprisingly long time to realize that that put it in the crime genre. I had just come out of a Ph.D. program in English, and I was reviewing literary fiction for the Chicago Tribune, and that was the world I was steeped in. And I didn’t really read a lot of crime, and I didn’t think of myself as liking crime particularly.

Then reading Gone Girl was kind of a moment for me—it helped me crystallize the structure that I needed for the book. When I embraced that aspect of it, the book made a lot more sense and came together a lot more easily. I got an agent and it sold kind of head-spinningly fast, because everybody was looking for—well, at that point, everybody was looking for the next Girl on the Train. Suffice it to say that my book did not turn out to be the next Girl on a Train, but I did end up with a two-book contract, and then I realized that most of the stories I wanted to tell fit into that genre anyway. One of my big literary influences from grad school was Henry James, who is a very psychologically twisty author, even though you don’t think of him as a crime writer. There’s certainly a lot of bad behavior and crime in his novels, there’s just not a lot of murder, but the head games are all there and that’s the part that I like.

I have a Ph.D. in English too, so I have to ask a question that you probably don’t get very often: what was your period as a scholar?

Yeah, I literally never get that question! I was a nineteenth- and twentieth-century Americanist, so I wrote my dissertation on James and Stein and the Modernist poets. A lot of the writers I ended up loving the most were expats—like Stein and James, and also Patricia Highsmith. I love those sentences that go on forever. I would write that way if I could.

The first thing I read of yours was a piece for Electric Lit on rape and the novel, and I read it because I’m also a fan of Clarissa—I remember the experience of reading it in graduate school so clearly. What made you want to go back to an 18th-century story of rape culture? Is that something you were thinking of in your work as a scholar?

Not really. I had read Terry Castle’s book on Clarissa, and I’d read a lot of Clarissa scholarship from the early feminist scholars, so it wasn’t like I hadn’t thought about Clarissa and rape. But it wasn’t until I was reading and reviewing contemporary literature that I started thinking about the foundational role of rape in the novel. If I could go back and write my dissertation on that, I probably would.

One thing I’ve noticed, reading the pieces you’ve written on Last Woman Standing, is that you don’t seem to see these stories as inherently exploitative. Some people think that with these stories of women suffering, there’s a rubbernecking aspect. With Last Woman Standing, were you consciously trying to change that narrative?

Well, there’s that prize for crime fiction that doesn’t have dead women in it that started a couple years ago. And it was kind of a controversial, divisive move in the crime community, even among women. And I think for good reason, because there’s a lot of room for disagreement about what counts as exploitation and what’s telling women’s truths. One thing we’ve seen in the Me Too era is that there’s so much weight stacked against women ever telling anyone what happens to them. And that creates a climate in which it can happen again and again, because if people don’t know that it happens to everyone, then each time it happens to an individual woman, she’ll just internalize that it’s her fault.

So I don’t think that not talking about something that’s so prevalent is the right tack. Now I think where there’s a lot of real questions is how this representation is managed, who does it, what form it takes. And that’s been an enduring conversation. Art has been mostly made by men, so that’s a question that women have had to grapple with. When women become a more dominant force in making all forms of art, that will be something we don’t have to agonize over so much—that this female suffering was made by a man, for the male gaze, for prurient reasons.

And there’s a wide range too—there are lots of ways of consuming any one piece of art. There can be room for exploitation and identification in the same piece of art. Something explicitly made to be titillating can also invite identification if it strikes a chord with a woman who’s felt that way. The key is having a lot of different takes, and I think that’s one thing that the boom of women writing crime fiction is giving us. Now there’s a lot of women writing about women’s suffering, and it’s not the only thing we want to hear them writing about, but there’s a wide range of ways of depicting that, and we can be a little bit more choosy, because it’s not just Clarissa or nothing.

I love the way you talked about agency there. It seems like you’re saying that if you tell a story that may be very dark or violent or hard to read, but it illustrates to people that this is something that happens, or could happen—that can be an empowering thing.

Yeah, Last Women Standing came out of seeing women disclose to each other that these things had happened to them, and watching what happened when one woman would say, “This thing happened to me, I feel really weird about it, what do I do?” and then all these other women would climb into the comments to say, “That happened to me too.” Sometimes it was, “That happened to me in college,” or “That happened to me last year.” Same guy, different guy. The strength that women can take from that community—it’s not a panacea, and that’s something that the book makes clear, but in that initial moment of realizing that it’s not just one woman, it’s not just two women—I mean, in the case of Bill Cosby, it’s like sixty women, and, unfortunately, we live in a society where one or two women’s voices just don’t seem to matter that much. But when you get a group of women together, eventually people have to listen.

So for me, writing about these things—I mean, Last Women Standing pointedly avoided the male point of view whenever possible. What I care about is how the women react to this trauma and how they manage afterwards. I wanted to represent a type of experience that a lot of women have had and that was actually criminal to some degree, but that rarely gets addressed. I wanted to see if I could make a crime novel out of something that everybody has experienced.

You’re so right, everyone’s had those conversations.

You’re so right, everyone’s had those conversations.

Yeah, they’re coming to light now, in the last year or so, but they’ve been going on forever. I can’t remember the first conversation like that I had—maybe high school, or even junior high. Women talk about it all the time.

We’ve been talking about these big thematic issues, but I wanted to ask you about craft too. How did you develop the plot? When did the comedy framing come in?

Well, I had been looking for something to write the second novel about. I had to write it on deadline, so I was actively looking for a plot. I was thinking about women’s relationships with each other, and I wanted to have that wider structural view. Good as Gone had these two characters interacting, but I wanted this to feel broader in scope, and to capture more of women’s experience.

So I was looking for a world to put this character in where a lot of stuff would have happened to her. I’ve done some comedy myself, and my husband does comedy, and our friend circle is heavily skewed toward comedy types, so I just had a lot of insight into that world. I was in these women in comedy online groups that were private and closed to men, and I had seen a lot of these conversations unfold, and they had made a big impression on me, so at some point I thought, “Well, why not just have her be in comedy?” And then I thought, “Well, I really only know one comedy scene and it’s Austin, so maybe we’ll just try her out as a comedian in Austin.” And it freaked me out a lot, because I was worried that I’d have to be funny, and I’m not really very funny when I’m trying to be. So that was intimidating, but it just worked for the story. I also wanted her to have already tried and failed in another place. She’d been in L.A. already when the book starts, and she’s kind of bounced back to where she came from and is grappling with that.

I think for every other writer I know, if you’re going to include a joke in fiction, you only write the punchline, and then you don’t actually have to be funny. So I loved that you wrote so many jokes for this novel, and that they’re really funny.

Oh, I still feel really self-conscious about the jokes. Some people will find them funny, and others will not. I asked my husband—because he’s a very good joke writer—I asked him how am I going to do this? So, he said, watch a lot of standup, and you’ll notice that a lot of it is really selling it with a stage persona, and a tone of voice. It took a little bit of the pressure off, to think, “I can write the jokes, but I can also try as best I can to describe the ineffable performance of it,” and that way, even if the jokes aren’t funny to the reader, it’ll be convincing when I say that the audience found them funny. That’s the important part.

Also, she does some of the same material twice in the book, and one time she’s bombing and the next time she’s killing. And that’s a big part of standup too, or really any kind of performance. Sometimes it’s the crowd, or the circumstance. There’s a kind of energy between the performer and the audience that’s really variable, and impossible to predict. If I have the jokes bombing one time and inexplicably killing the next, I think the reader will realize that the joke itself is kind of arbitrary.

I don’t want to give any spoilers, but the climactic scene of the book is very violent, and very full of action. Can you tell me, from a craft perspective, how you went about writing it?

Action scenes are the hardest for me to write, and I think most people have trouble writing them. I just had to write it and rewrite it a hundred times. An action sequence is like a dance, it’s very choreographed. And I’m sure that some people know how to plot that out in advance, but I do not. So I’m picturing the movie in my head, and I have to have a little floor plan in my head of where the different rooms are. And then I just ended up writing and rewriting it again and again until all the details made sense to me.

Within the scene, there’s a rising action and a climax and a falling action, so the shape of the action can’t just be one big thing after another. You have to build suspense within the scene just as you do within the overall structure of the novel. And then in the end, it’s just a lot of revising. I did the same thing in Good as Gone—I knew where the climax was going to be, I knew the setting and the characters that were going to be there, and then I just kind of left it blank for a long time. I scribbled something in, and then I had to go back and rewrite it a bunch of times because it wasn’t climatic enough.

One reason I think that I ended up in crime writing is because I’ve always thought I was really bad at plot. And in crime writing, you can’t get away with not writing a plot. So I think there’s a little bit of overcompensation there—like, I learned how to plot to write my first crime novel. And it was only after I decided that it was a crime novel that I could figure out how the plot was supposed to work. Because crime novels are very highly structured, they have to have structure. There are a few exceptions to that, but a meandering crime novel is usually not something that succeeds.

You’ve been on tour for a few weeks now. What responses are you hearing from readers?

It’s hard to say. On tour, you’re in front of people, so I’m not sure they’re going to be one hundred percent honest. Or they haven’t read it yet—sometimes they’re just buying it. But in reviews—the murky Goodreads reviews that you’re never supposed to read as an author is probably the place to see the most honest responses, and also sometimes the harshest responses.

It’s hard to say. On tour, you’re in front of people, so I’m not sure they’re going to be one hundred percent honest. Or they haven’t read it yet—sometimes they’re just buying it. But in reviews—the murky Goodreads reviews that you’re never supposed to read as an author is probably the place to see the most honest responses, and also sometimes the harshest responses.

I’d have to say it’s a really mixed bag. I see readers who are thrilling to how angry the book is, and are delighted with that, and of course that’s the response that I hope people will have. But I see readers who are really disturbed by it too. There’s a protagonist and an antagonist, a kind of doppelganger character, and people often seem to like one and really hate the other. Or they think one of them is really believable and the other one isn’t. And I have heard that some people find both of these women really unlikeable. All I can say to that is, “Yeah, they’re not good people.” I don’t want to write about good people.

Maybe that’s one of those conversations that writers are just having among themselves on Twitter, about women characters and likeability. But I’m amazed that that’s something that people still are demanding from literature.

Yeah, it’s really strange. I was on this podcast called Unlikeable Female Characters a few weeks ago, and like I said on that show, it’s not just men demanding that female characters be likeable. Women hold female characters to a higher standard as well. I think there’s a sort of defensiveness there. But all you have to do is look at the long history of shitty men in literature to realize, actually, we love reading about unlikeable characters, but we seem to have this hang-up if a woman protagonist and she doesn’t behave well.

It’s like people need women to be perfect to find them sympathetic.

You know, it’s funny, but I think unlikeable has started to be kind of a bad word. And then I starting hearing even from my publisher and my agent, “characters should be relatable, even if they’re not likeable.” And it’s just such a hard concept for me to grasp. It’s so obviously subjective, what’s relatable. You watch Breaking Bad, and you’re forced to identify the whole time with this protagonist—I mean, there’s nothing relatable in that protagonist! He’s arrogant, he’s a petty tyrant—but it’s a great show.

And I think we’re missing something about the fact that relating is an action on the reader’s part.

We make it a noun as if it’s a quality that’s inherent, but relating is a verb—something that readers do. You can choose to relate to someone, you can choose to empathize with them, even if they’re very different from you. That’s what literature is supposed to be all about—at least that’s what the humanists are constantly yammering on about. But I think the burden is on the writer to make the book interesting enough that you don’t care whether the characters are relatable. I think relatability is one way of creating stakes, but there’s a lot of ways to create stakes. Suspense is a way. And beautiful language is another thing that the reader can become invested in. I feel like my job as a writer is to keep the reader turning pages, and if the reader wants to make the leap to identify with someone who’s a bad person—I mean, I certainly do when I read, but if you don’t want to do that, that’s fine.

What other women writers in the genre would you recommend? Who is doing exciting work?

When I wrote the book, I was reading a lot of Muriel Spark. I don’t think she’s really in the genre, and yet her books have a lot of crime and shenanigans in them. Patricia Highsmith is cited to death, but it’s for good reason. Here’s a canonical female crime writer who had literally no interest in likeability or relatability. Her characters are loathsome on purpose. In terms of who’s writing right now, Oyinkan Braithwaite’s My Sister, the Serial Killer—that one really blew me away. It’s short and funny and makes me want to see what she’ll do next.

I always recommend Tana French for anybody whose more used to reading literary fiction and don’t think they could ever read something with a detective in it—that’s kind of the gateway drug. Everything she writes is intensely pleasurable. Sarah Gran is also someone I always recommend—her Claire DeWitt series is like nothing else. It’s totally breathtaking—really funny and heartbreaking. There’s a bunch of debuts coming out that are pretty great this year. Megan Abbott and Laura Lippmann are names that people throw out there a lot, but for good reason. I also loved Temper, by Layne Fargo, based on a Me Too case in the Chicago theater world; Blood Orange, by Harriet Tyce, a twisted, nasty domestic suspense tale starring a couple of thoroughly unlikable woman; and Hunting Annabelle by Wendy Heard, a vastly entertaining, tables-turning, gothic serial-killer love story set in 1980s Austin.

Amy, thanks so much for talking to me today. It’s always fun to connect with a fellow Jamesian.

You know, it’s funny that we’ve ended up talking so much about academia, because the novel I’m working on now is actually set in a Ph.D. program! And if there’s one place where you could totally believe a sordid murder would happen, it’s in a humanities department. A department full of kooks and weirdos with murderous intent.