Editor’s Note: As we approach our tenth year of publishing Fiction Writers Review, we’ve decided to curate a series of “From the Archives” posts that we’ll re-publish each week or so during 2017. Some of these features are editor favorites, some tie in with a new book out from an author whose worked we’ve covered in the past, and some are first conversations with debut authors who are now household names.

This week we’ve returned to Lee Thomas’s interview with Aravind Adiga, which was originally published on April 15 of 2009. Adiga’s new novel, Selection Day, was published by Scribner last week.

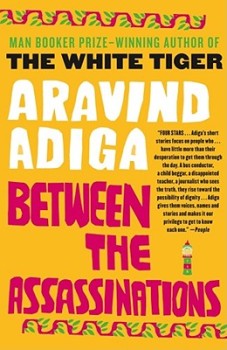

Before his first novel, The White Tiger (Free Press), debuted in 2008, Aravind Adiga had already had a substantial career as a journalist, writing for the Financial Times, Money, the Wall Street Journal, and Time. The White Tiger won the Man Booker Prize in October of 2008. The novel’s protagonist is Balram Halwai, and his indomitable voice shapes a story of struggle, retribution, and defiant survival set in present-day Mumbai, bursting at the seams with people straining against the bonds of society and fate. Adiga’s second book is a collection of stories called Between the Assassinations (Free Press), which he wrote before and during The White Tiger. Between the Assassinations was published in India in November of 2008 and arrives June 9 of this year in America. Through characters from every walk of life, Adiga assembles a collage that richly details life in the coastal town of Kittur. We caught up in March over email (due to the 12 ½ hour time difference between Mumbai and San Francisco).

Interview:

Lee Thomas: You began your career as a journalist. What caused you to make the leap to fiction?

Aravind Adiga: The leap was the other way–into journalism! I had always wanted to be a writer, but there’s no way of supporting yourself in India while you write, as we don’t have MFA programs or writing fellowships. I became a journalist to support myself while I wrote my novel–and also to see more of the country that I was going to write about. I knew always that one day I would quit to write my book.

Who are you reading these days?

Among Indian writers, I admire R.K. Narayan and V.S. Naipaul above all others. I don’t know any other writer in Mumbai, and I am not part of any literary set–I don’t think these things even exist in India. So my reading tends to be idiosyncratic, and in many ways, nostalgic–I am always happy to find a book that I discovered in New York or Oxford. In the past week, I’ve been re-reading Isaac Babel’s Red Cavalry stories, with the fine introduction by Lionel Trilling; Walt Whitman’s poems–I’m trying, for the tenth or eleventh time, to memorize “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d” beyond the first stanza; and Flaubert’s Sentimental Education. An Indian magazine that I read regularly, India Today, sometimes carries a review of a new novel published in America and I try to find it here if it looks interesting.

Before the Booker, your book was a bestseller in India and had varying degrees of success outside your borders. What, if anything, has the award changed for you?

The award has changed very little in my day-to-day life in Mumbai. It has made my life as a writer easier in many ways–certainly it’s easier now to get published: my second book, Between the Assassinations, will be published this year in America. It does mean that there are more distractions, too, and less time to write.

Between The Assassinations, which deals with life in Kittur, is a collection of stories you actually wrote before The White Tiger. Do you have a particular connection to the city? Why did you choose a single locale for your develop your cast of characters?

Between The Assassinations, which deals with life in Kittur, is a collection of stories you actually wrote before The White Tiger. Do you have a particular connection to the city? Why did you choose a single locale for your develop your cast of characters?

Kittur is an entirely fictitious town: it doesn’t exist any more than Faulkner’s Jefferson [the county seat of Yoknapatawpha County] does. I made it up, to tell the stories of the people in it. Finding that most Indian fiction told the stories only of a particular kind of person–upper-class, upper-caste, educated (and often expatriate)–I wanted to tell the story of an entire Indian town: every class, caste, and religion. An entire cross-section of an Indian town–Muslim, Christian, Hindu, upper-caste, lower-caste, rich and poor–appear in these stories. In a broad sense, Between the Assassinations is the prelude to The White Tiger; it tells the story of India in the late 1980s–in the period that falls between the assassinations of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi (1984) and her son Rajiv (1991). With the death of Rajiv Gandhi, came one of the biggest changes in India’s history: the opening up of its socialist, protected economy to globalization in 1991. The White Tiger is the story of the new India created by this globalization. The two books are meant to work as one story.

The White Tiger seems the evil twin to something like Slumdog Millionaire–realist, brutal, and without a neatly-tied ending. Both portrayals have something to say about modern day India, but for you, where does the truth lie?

I can tell you this much: if I were born poor (as most Indians are), and I were a servant, I wouldn’t be pinning much hope on winning a TV show in order to win my freedom.

Your stories contain the tension between have and have-not, those on the inside and the disenfranchised of modern Indian society. Where does the germ of a story begin for you?

I’m a complete misfit in India. I don’t do anything right. I don’t live the good life that a middle-class person returned from America should. I don’t own a car, though I could; I don’t keep servants, though I should. Through sheer incompetence and ineptitude, I’ve discovered what life is like for the majority of Indians. I take public transportation, which I shouldn’t; I eat by the roadside, which is dangerous; I talk to prostitutes and pimps. My stories follow from my experiences–they are the stories of a fallen and alienated middle-class boy.

Every other country in south Asia–Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka–is on fire; every other country is going through a civil war because it has fallen for its own myths. In Pakistan, the myth of the three protecting A’s–Allah, America, Army–have destroyed the country. In Nepal: the myth of the divine monarchy.

In India too, we have our myths–God, Gandhi, and family–but we have always questioned these myths enough, we have allowed room for dissension. And so we alone thrive while South Asia burns. In the past ten years, however, these dominant myths have grown stronger and the space for self-questioning has diminished within India. The majority of the country is still poor–up to 700 million Indians live in poverty–and the poor are no longer happy to keep quiet. The government isn’t investing in the schools, hospitals, and jobs that will allow these poor people to rise. Aspiration grows, but not opportunity. This can only lead to trouble. Anyone who points this out is called a traitor.

The way the Indian elite has reacted to Slumdog Millionaire and The White Tiger–with hostility–proves to me the fundamental accuracy of both works. Both are ultimately mild, middle-class critiques of the state of things in the country. If the elite can’t swallow either of these, if they react with such naked fury to works that question their right to rule India, then this can only be a sign of trouble ahead.

The White Tiger not only feels like a timely book, but one that is needed. Why do you think this is?

The White Tiger not only feels like a timely book, but one that is needed. Why do you think this is?

Everyone has servants, and the story of a servant who steals from/kills his master is the most obvious story to write about! Unless you are so much a part of the system that you can’t see what’s right in front of you. If you pay the price–alienation and isolation–then you reap the rewards here–which is to say, you see what’s obvious. If you put yourself through punishment, you will earn your wages at the end. All you have to do is write a story about the poor–who are the majority of this nation, as they are the majority of Asia, the majority of Africa, and Latin America–and the middle class critics and writers here will scream that you are being polemical and preachy. It could be a story of a poor woman crossing a road, and you’ll be accused of being a Leninist. But this touchiness is an opportunity: because the middle-class here, like in America, is mostly liberal.

I told you, perhaps, that my book has always sold well in India; it has now sold over 150,000 hardcover copies here, and the expense of a book is a significant sum of money for most Indians. There is a hunger among readers in India to be told other stories, to read challenging, even confrontational/disturbing stories; but this hunger is not being satisfied by our literati here. Rather than be upset, I see it as an opportunity of some kind.

My friend in New York, Ramin Bahrani, is an Iranian-American filmmaker, who has made several films about working class people in New York, and has now won a name for himself in the indie film scene. The New York Times Sunday magazine ran a long story featuring him and others, in a story called “Neo-Neo-Realism.” We were undergraduates together at Columbia. Then I went to Oxford for my M.Phil and he left for Iran; I returned to America in 2000 and met him again. His work has been a huge influence on me; the two films quoted in the article, Chop Shop and Man Push Cart, are the reason I could write The White Tiger when I returned [to India].

He tells me there’s a great hunger now in Hollywood for neo-realist stories. Perhaps this is true of all of America. Certainly, the 1930s were when so many realist masterpieces were written–The Grapes of Wrath, for instance, which I love! This could be a time when neo-realist work strikes a chord with readers.

Why neo-realist fiction? What can a piece of art achieve/reach/lay bare that pure reportage or documentary might not capture?

What fiction can provide, which reportage often cannot, is narrative, ambiguity, and moral complexity. There should, ideally, be no “message” or “point” to a novel; it should keep you thinking and entertained and disturbed years later too.

Further Resources:

- These short stories by Aravind Adiga are available online — “The Elephant” (from the New Yorker) and “The Sultan’s Bakery” (from the Guardian).

- The author writes about Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man for the Independent.

- The BBC covers Adiga’s Man Booker win.

- And here is another interview with the writer, this one from NPR.